Fire Emblem: Three Houses gives you supreme control. In battle, you peer down over the men and women of your chosen house and shuffle them around like board game pieces. They obey instantly and without question, no matter how ill-advised your orders might be, even if the result will put them out of action for good. Among them, your main character stands out. Equipped with a powerful relic weapon and charged by an inner force, they stride across the battlefield, tearing through enemy soldiers.

When the fighting is done and you’re back in Garreg Mach monastery, your unique status again comes to the fore. It’s not only that the great archbishop Rhea gives you special treatment and appoints you to a professorial role despite your scant qualifications. You also have a remarkable ability to befriend every individual and get to the heart of their deepest problems, offering advice or aid that will see them grow. And only you can look around the classes of other professors and choose who you might persuade to defect and join your own.

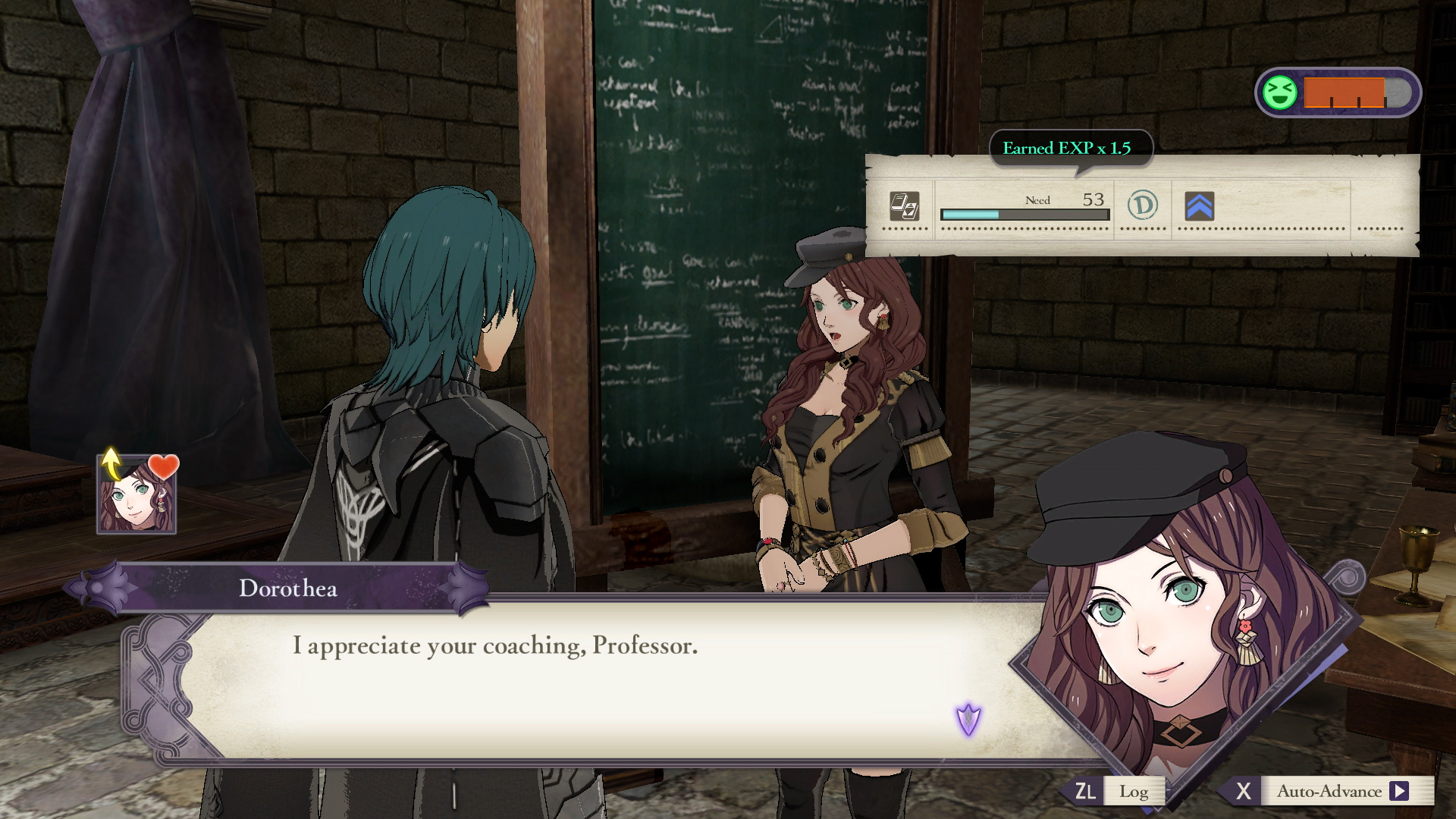

As a teacher, you’re free to mold your students into whatever form you deem fit, planning ahead to plot their whole military careers. They may want to focus on certain skills, but if their desires clash with your intentions you can easily redirect them. You single out individuals for training in specific areas and put on extra seminars if necessary to develop them further. Under your guidance, the laziest of pupils can transform into frontline armored warriors, and timid pacifists can evolve into ruthless assassins. It’s a power fantasy in which you determine not only who lives and who dies but what they may become.

Or is it? Dig a little deeper, and how much control do you really have? What if you aren’t the agent here but a subject being pushed around by unseen forces? It seems obvious when Three Houses takes its big narrative steps, as different nations vie for position and each leader has his or her own secretive goals to fulfil. But even at the micro level, in the marriage of the game’s relationship building, teaching and combat systems, you might start to wonder if it’s really you pulling the strings. What if, most of all, it’s the defining features of your main character—their strength and popularity— that makes you susceptible to manipulation?

The overarching story is an important part of this, with its three major factions each plagued by internal political conflicts and kept in an uneasy peace by the apparent unifying power of the church. Whichever house you align with—in a decision you must make before really knowing anything about the situation—you make yourself party to one grand scheme or another, potentially with no way to change course. And, naturally, no one tells you upfront what they’re doing or what they want from you.

It’s not long before you’re fighting morally suspect battles, or witnessing the merciless side of the saintly archbishop, while your house leader plots behind the scenes. But still, they all seem so earnest and concerned about truth and justice that even once you do find out what’s going on, it’s not clear who’s in the right. Take Edelgard, leader of the Black Eagle house and princess of the Adrestian Empire. Her reasoning appears sound and she claims to have no real appetite for war, but then she’s determined to realize her goals at any cost. When that eventually sees you having to fight old comrades, whatever you do feels like a trap.

It’s not only the major players that affect you. When you first meet the monastery’s students and faculty, it’s easy to be lulled into a sense of apathy, as each seems perfectly one-dimensional. Raphael is strong and hungry. Bernadetta is socially awkward. Sylvain is a notorious womanizer. And so on. But over the months, as you run into them around the monastery, you get their views on current events, offer topics of conversation over tea, and listen to support dialogues that reveal their traumas, hangups, and hidden charms. Even many of the entitled nobles that loiter the halls reveal a pleasant side, with their flaws partly excused by complex family histories.

At the same time, the game is designed so that the more familiar you become with these characters, and the more you nurture those in your squad, the more it expects you to do for them. This becomes especially evident in combat, as your battlefield decisions are increasingly clouded by emotion. For all the chess analogies you might throw at a grid-based tactical war game, there are no actual pawns at your disposal, only various flavors of knight, rook, and bishop, with the main character and house leader standing at their center as king and queen. And because you aren’t really a general commanding soldiers but a teacher directing students, their safety is as important as your victory. It’s a basic leap of empathy that as you learn more about their dreams and their backgrounds, the more their deaths hurt. You become a slave to getting each battle exactly right.

In fact, your combat performance strengthens the bonds further, as the way your team members fight deepens your perception of their characters. When Bernadetta, for example, becomes a deadly sniper with dozens of kills under her belt, you see a side of her that’s not explicitly written into the script. Lorenz, another student, is a preening noble convinced of his superiority and status as a peerless marital match. He’s slimy and snooty, but with his strong sense of noblesse oblige—the duty of nobles to protect the common folk—he isn’t the coward you might expect. Train him as a cavalier and send him charging through enemy lines to rescue civilians, and it accentuates that bravery, regardless of his motivations.

Your growing feelings of attachment then combine with the particulars of the battle system to subtly subvert your sense of empowerment. The best way to protect your charges is to play safe, so although you always have dozens of options, sticking to the basics will usually see you through. Also, the distinct strengths and weaknesses of specific combat matchups from older Fire Emblem games are played down, making victory depend more on character stats than creative or risky play. It’s often best to group tightly together and play reactively, letting the positions of enemy reinforcements dictate your strategy. And if you do get caught in a tricky situation, the handy rewind feature will see you repeat until a sensible path is discovered.

Meanwhile, in the monastery, the methods of relationship building and recruitment undermine the notion that you’re in charge. Support rankings and motivation are key, leaving you running around pandering to students’ egos and laboring for their attention. In conversations, when you have the opportunity to speak, it’s not what you’d like to say that matters, but second-guessing what your interlocutor might want to hear. Maybe you’re picking up lost items that students and staff have carelessly left lying around, hoping for the owner’s gratitude when you return them, or pestering individuals to have dinner or tea with you and giving them gifts to smooth things along.

Your supposed authority is thus based on a constant need for recognition, begging these characters to aid your questionable war efforts or at least change sides so you don’t end up having to kill them later. The more they snub you, the more you need to work to win them round, and the more they make you want to do it. As you seek to increase their motivation, they use your desperation to motivate you. Because you’re powerful and because you’re popular, you’re an especially useful servant. They realize you can be talked into helping anyone, and whether it’s a sidequest where one of your squad just happens to invite you along, or the tide of a war that’s raged for five years without an end in sight, they know the problem can only be solved if they can put your attributes to use.

So it’s as an RPG hero, an individual who’s so powerful and so amenable to others’ demands, that you become the tool for each faction to try and achieve their aims. You don’t have to help anyone, of course, except the leaders you align yourself with, but Three Houses plays on your sense of empathy, your inquisitiveness and your completionist desires to reel you in. As such, while the lives of these characters are certainly shaped by your involvement, the path of that involvement is shaped by them in a way that occurs so naturally you may not notice it happening. It’s almost as if they realize that they’re in a game that you, the player, will always (eventually) win. They can’t beat you in combat, but they can make you work for them, to secure them a positive epilogue, while making you believe you’re calling the shots. As much as they are still pieces in your game, you are also a piece in theirs.

Header image: Nintendo

Jon Bailes is an independent games critic and researcher from the U.K. He is author of Ideology and the Virtual City: Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism (Zero, 2019). You can follow him on Twitter @JonBailes3.