There aren’t many game villains quite as nasty as Katana Zero’s V, a Russian mobster who gets his kicks from torture and murder. But when you register your disgust at his extreme sadism, he quickly responds that, actually, you kill more people in one night than he has in his whole life. And he’s got a point. In Katana Zero you tear through various facilities towards assassination targets, often hacking down dozens of henchmen on the way. Yet V’s comment hits home not merely because of the sheer numbers, but the motivation: He knows as well as you do that you’re in it for the enjoyment.

Games like Katana Zero, Hotline Miami, and My Friend Pedro present the acts of digital violence we’ve committed since the arcade era back to us in a context that reveals their horror or absurdity. Of course, it’s no revelation that we play violent games for fun. But the grim tone of Hotline Miami and Katana Zero, or the dark humor of My Friend Pedro, prod us to ask ourselves why we enjoy the simulated violence so much, and how much of it we can take.

What I find especially interesting is how this experience mirrors the far more mundane moral dilemmas we face as we attempt to get by in today’s society. As I write in my book Ideology and the Virtual City, games are uniquely equipped through their blend of narrative, aesthetic style, and interactivity to explore our complex relationship with modernity, and how we accept or criticize its demands. In this instance, the question is one of the rampant consumerism society expects of us, even in the face of growing awareness that such behaviors are unsustainable. Why do we continue to participate in a system that is in many ways bad for the world and ourselves? Hotline Miami, Katana Zero and My Friend Pedro emphasize through their narratives and design that our complicity rests on both conscious rationalizations and an underlying sense of enjoyment that can make us feel guilty for playing along.

Credit: Devolver Digital

Confusion, coercion, corruption

At one level, these games use their narratives and structures to provide a kind of rational cover for our abhorrent deeds. This is a kind of justificatory logic that helps us deny responsibility, and it comes in three forms: confusion, coercion and corruption.

Confusion describes how the main characters in these games are plagued by memory loss and hallucinations, making them unstable and unsure of what they’re doing. Many games turn us into amnesiacs, as we begin by controlling a character we know very little about in an alien reality. But here, the sense of disorientation is deliberately heightened, and it helps excuse our behavior. In My Friend Pedro we’re guided by a talking banana, while Hotline Miami establishes that what we’re seeing might not be real. Since we don’t know exactly why we’re killing, we can’t be sure it isn’t justified. Or, if we’re completely insane, we can hardly be held accountable for our actions.

As for coercion, regardless of our character’s mental state, these games simply give us no choice but to kill. In Katana Zero and Hotline Miami, there’s the implication that any refusal to complete assignments will put us in danger. But even at a structural level, we can’t progress through the game without getting neck-deep in murder. In most cases, it’s the only mode of interaction available. At the end of Hotline Miami’s first mission, you’re interrupted disposing of evidence in a back alley by a homeless man. As he comes at you with a bat, you have to take him down. Afterwards, your character throws up on the floor in disgust, but since you couldn’t do anything else, are you responsible?

Corruption, finally, is found in foul and depraved locations in these games, which are so packed with unrepentant villains that it seems perfectly acceptable to erase them. Like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, you can feel that you’re cleaning up the streets even as you contribute to the mess. Once you’ve met V in Katana Zero, you can’t not want him dead. Similarly, in My Friend Pedro, the first enemy we see is one Mitch the Butcher—illegal gun smuggler, dealer of dubious meats, and all-around bastard. The world will be better off without him. And it’s not only the key antagonists that deserve it. Even the way the nameless goons attack, with clinical, ruthless force, makes sympathy for them impossible.

Credit: Devolver Digital

Enjoyment (and guilt)

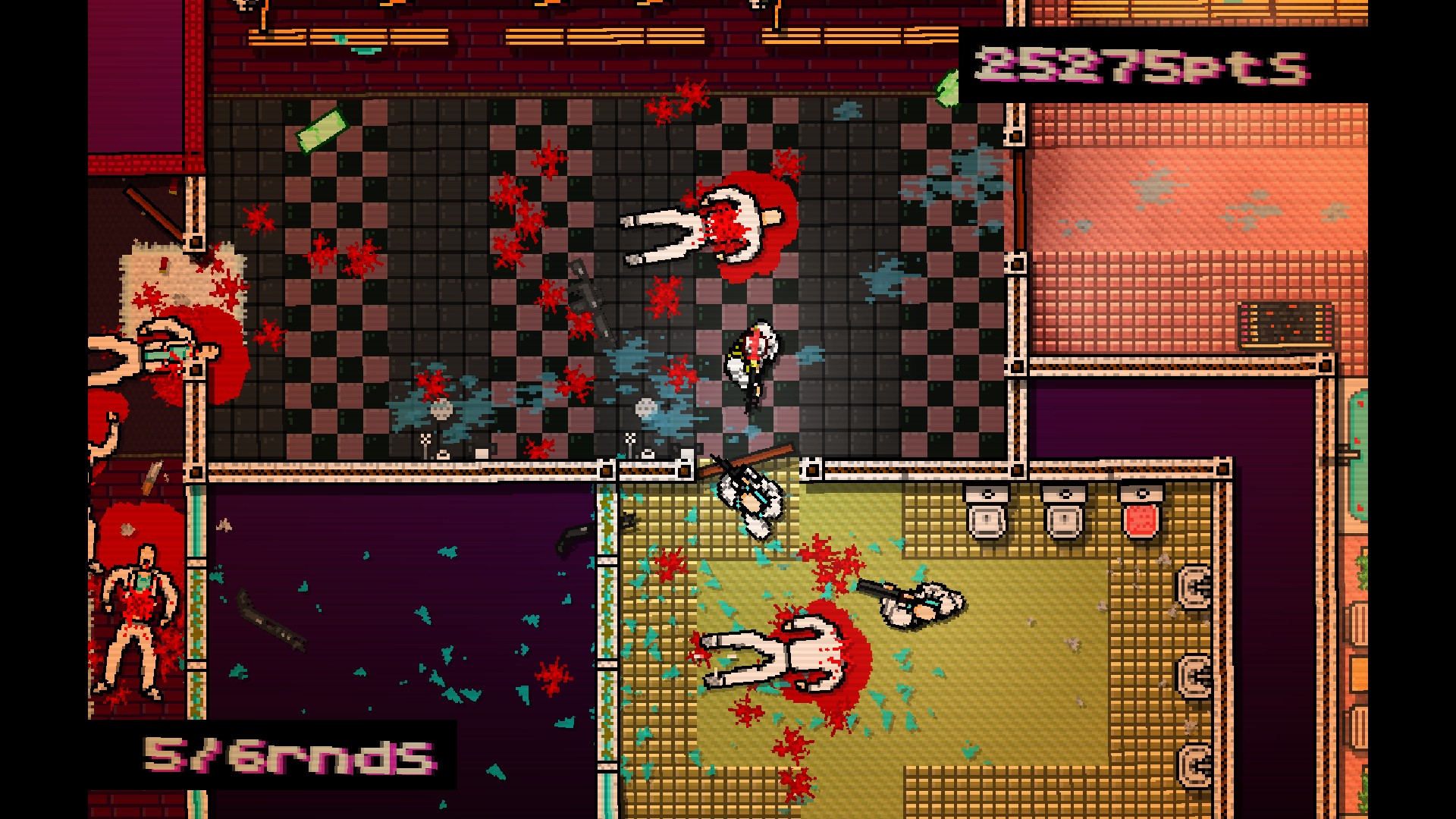

On another level, the games know that we’re really here for the lurid settings, the challenge, and the brutality, and so go to great lengths to make the action stylishly pleasurable. Here, murder is a dance amid garish colors and pumping electronic tunes, where we coolly dispatch foes in slow motion, spinning between their bullets or deflecting them back at their owners. These games want us to slip into exhilarating rhythms of quick, focused executions, turning short bursts of decisive and creative slaughter into satisfying sprees. When calm returns, the scene is a bloody mess, and a testament to our fine handiwork.

This enjoyment overshadows any narrative motivation. In My Friend Pedro, the first gangster you kill is a matter of self-preservation. But then Pedro, the aforementioned talking banana, simply announces, “Well, I guess you’ll just have to kill them all now.” So off you go, with a knowing wink that no persuasion was ever really required. And about that homeless man in Hotline Miami. How long does it take for you to accept the forced choice and beat him to death? A second? Two? You weren’t exactly reluctant. Or in Katana Zero, where you can skip dialogues by interrupting your interlocutor, cutting them off mid-sentence with increasing rudeness. Is that because you’re so impatient for your next fix of violence?

It’s all part of a set up. These games give us the rational, conscious reasoning of the narrative to let us off the hook in terms of taking responsibility, only for our perverse enjoyment to twist it back towards us. They induce a sense of guilt, not from the wider moral consequences of our behavior but from our inability to stop wanting more. In Hotline Miami, it’s put to us in the form of a simple question: “Do you like hurting other people?” No matter how much we’re only doing what the game demands, it’s hard to deny that we do. It’s why we signed up in the first place.

Credit: Devolver Digital

Reality…

This relationship between enjoyment and narrative justification is remarkably similar to how we engage with social pressures. One way to understand this is through the ideology theory of philosopher Slavoj Žižek, which suggests that a kind of hidden, excessive enjoyment is at least as important in explaining our actions as what we say believe about them. Simply put, when we commit acts we know to be wrong, we tell ourselves stories that explain why our actions contradict our values, but that’s not the full explanation. We also do bad things because, on a baser level, transgression just feels good.

Even when we’re pressured by outside expectations to commit harmful acts, we often practice a kind of “surplus-obedience”—we voluntarily go beyond what is necessary. As Žižek says, the fact we’re following orders doesn’t abolish our responsibility: “One is responsible in so far as one enjoys doing it.”

Credit: Devolver Digital

We’ve seen how this works in our games, but it’s a principle that applies just as much to mass consumerism. Most of us acknowledge (or have at least encountered the idea) that the level of consumption required to sustain contemporary society is unsustainable and highly destructive, impacting our environment and our collective physical and mental health. Yet we continue to participate, often buying more than we need, contributing to a culture of waste and individualism.

Of course, we can devise convincing explanations for why we behave this way. First, the networks of resource extraction and social structures are too complex to keep track in full. No one can easily determine the exact origin and environmental impact of every product they purchase—especially when some companies provide misleading information to that end. Second, modern lifestyles require a lot of stuff. If we want to fully participate and connect with those around us, there’s a perpetual feeling we need to own this or that novelty, just to keep up to date. Third, there’s nothing much any one of us can change as individuals. Major corporations seeking short-term profits have a far greater influence on politics, and the environment might already be beyond saving. Confusion, coercion, corruption.

But regardless of how true these and other rationalizations might be, we also really enjoy consumerism. There’s a thrill in buying something new, even as we understand the accumulated consequences. And because of that thrill, we can’t fully escape the sense of responsibility, no matter how much we repress it. Yes, we’re always told to buy more, but that doesn’t make us any less guilty.

Credit: Devolver Digital

…and fantasy

There’s one more dimension to this story, however. Returning to our games, especially Hotline Miami and Katana Zero, we might consider how, by making us feel bad about our enjoyment, they direct us away from their own responsibility. After all, as guilty as we might be for playing, at least we didn’t actually design the system. Who thought up this hideous world for us to enjoy? How much enjoyment did they get from concocting these bloody scenes? It’s as if the game itself still gets to enjoy the violence it meticulously displays through us, while offloading all the guilt.

Again, this reflects a social system which tends to make individual consumers responsible for their enjoyment in a way that helps the system itself avoid blame. We’re asked to consume ethically, watch what we eat, recycle and reduce our carbon footprints, while the economic structure thrives on unhealthy products, waste and financial risks. Looked at this way, it’s not that we shouldn’t feel responsible, but that we should feel responsible collectively rather than individually—not for everyday choices so much as failing to hold the system to account.

Credit: Devolver Digital

My Friend Pedro, Hotline Miami and Katana Zero offer a kind of fantasy resolution to our situation, not least because they have objectives and endings that create resolutions for seemingly inescapable problems. In their worlds, depravity isn’t a limitless system but a criminal conspiracy, with an organizational head that can be killed to end the madness. A way out becomes available that isn’t apparent in reality. But it’s a strange sort of way out that involves continuing to participate in and enjoy the same destructive behavior, even escalating its scale, until the whole structure collapses. As an achievement, it’s quite nihilistic, leaving nothing but a question mark over what comes next.

But as much as these games coax us to destroy and enjoy, we should remember that they also hint at something else. In another scene in Katana Zero, two mysterious beings give you a straight choice between life and death. Either they kill the police surrounding you and you continue your mission, or they kill you. Select death and it’s over—the credits roll and you return to the title screen, at least until you reload your save and make the opposite choice. But what if this really is the “good” ending? What if it’s actually fine to just stop participating, to break the loop of enjoyment and guilt? In real life, this isn’t literally a question of life and death, but of how we live.

Can we, in some sense, stop playing the game?

Header image credit: Devolver Digital

Jon Bailes is an independent games critic and researcher from the U.K. He is author of Ideology and the Virtual City: Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism (Zero, 2019). You can follow him on Twitter @JonBailes3.