When the present isn’t looking too great, and the future is uncertain, it’s only natural to look back on the good old days and wonder what made them so special. Maybe, just maybe, if you can recapture the magic of those times, the future might look brighter.

Battlefield: Bad Company 2 turns 10 years old today, at a time when the franchise is seemingly at one of its lowest points. After having uninstalled Battlefield V in the most melodramatic fashion possible, I recently returned to the game that started my decade-long affair with the franchise, fully expecting to confront my own rose-tinted nostalgia.

As it turns out, you can go home again. At least, to an extent. Bad Company 2 might be rough around the edges when compared to more contemporary shooters, but at its core, it’s still as good as it ever was. But a decade is a long time, and some things can’t help but change.

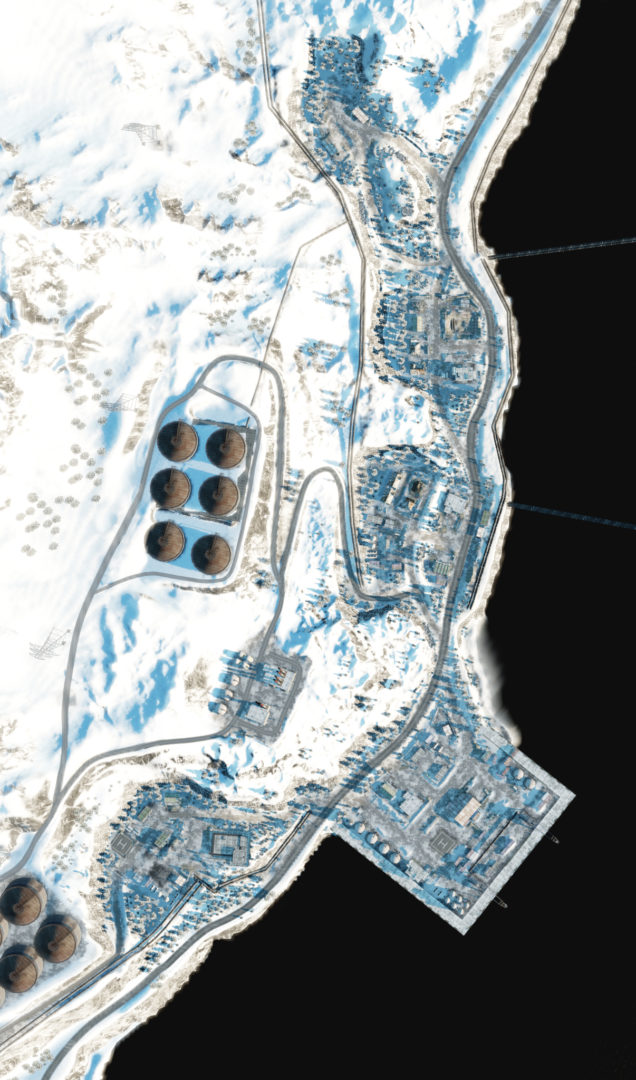

Credit: EA

I was 23 when Bad Company 2 launched in 2010—a year and a half out of college and in my first year of grad school. The year or so I’d taken off of school, I’d moved back in with my parents and was working at a Caribou Coffee in my hometown of Solon, Ohio, a half-hour drive from Cleveland, getting high with my coworker behind the dumpster and drinking too much in my off-hours. I was horribly depressed, so I thought that going to grad school 45 minutes away in Akron would help. Of course, I was wrong.

After moving to Akron, little about my life changed. Sure, I had my own apartment, but I was still working at Caribou when I wasn’t in school or tutoring undergrads. I was keeping busy with school, but I was still drinking way too much and getting high, and I was still playing a ton of video games.

The difference was that I’d met two guys from the Caribou in Macedonia who happened to transfer to the Caribou in Akron around the same time that I had. One was a former skater kid who was taking a break from school at the moment, and the other was an aspiring writer like myself who dropped out of pre-law and was trying to figure out what the hell to do with his life. An academic nerd, I’d never had friends like Bryan and Mason, who I saw as free spirits in that sort of rundown, hardscrabble, Rust Belt way. Bryan and Mason had been friends before I met them, and I spent the first few months hanging out with them simply worrying if I was fitting in and why the hell these guys wanted to hang out with a nerd like me in the first place.

But we did have several things in common, namely that we all smoked cigarettes, drank a lot, and loved getting high and playing video games. We’d spend hours after work, in the dead of Ohio winter, at Bryan’s apartment, blasting Hot Chip, ashing cigarettes into empty (or sometimes, by accident, half-full) beer cans, and playing the trashiest indie games that Bryan could find on Xbox Live—Maids with Balloons and Try Not to Fart were our usual go-tos, though sometimes we’d put on Techno Kitten Adventure or Rez, depending on if one of us had weed.

At the same time, one of my other best friends, Nick, had moved to Columbus with his girlfriend. Two hours wasn’t that far apart, but I wasn’t seeing him every day like I had in college. Nick was probably one of the biggest reasons I didn’t fully lose my mind when I was living at home. As down as I was, he was usually there to play Halo 3 with me and excuse my drunken shenanigans, such as pretending to be an annoying little kid on the game chat who had no idea how to play the game. For some reason, I thought this was hilarious.

Eventually, my two worlds collided when Nick suggested we try Bad Company 2.

The scope of competitive gaming has changed a lot in the last decade. Sure, there have always been LAN tournaments for games like Halo and Counter-Strike, Evo’s been around since 1996, and Billy Mitchell has been hunting for high scores since the ’70s. But these days it seems like pretty much every multiplayer game needs to be geared towards a more competitive mindset. There are probably many reasons for why multiplayer games have focused more on being competitive rather than creating fun experiences, though the one that sticks out to me is the impact that streamers are having on the industry.

Ninja recently trended on Twitter for scolding players who just want to have fun in a game without having to feel overly competitive. “The phrase ‘it’s just a game’ is such a weak mindset,” he wrote. “You are ok with what happened, losing, imperfection of a craft. When you stop getting angry after losing, you’ve lost twice.” God forbid players don’t have a negative emotional reaction for not winning in a video game.

The omnipresence of streamers like Ninja, DrDisRespect, and Tfue in the multiplayer landscape promote, intentionally or not, a toxic, capitalistic attitude towards gaming that’s the equivalent of a Little League coach telling his 8-year-old players that “second-place winners are first losers.” The concept that winning isn’t everything is completely antithetical to streamers’ careers, because if they’re not winning, then they’re just loudly yelling at a camera in front of a greenscreen. In part, it’s a reaction against the “participation trophy” philosophy that (also wrongly) dictates that everyone who plays is a winner. But in swinging so far back towards alphaness and domination, they’re reinstating the toxicity of competition—one that they’re broadcasting to millions of people, many of them children.

Credit: Xbox Game Studios

What’s really interesting is how this attitude has found its way into actual game design. The first time I actively noticed this was when Halo 4 transformed the series from a floaty, slower-paced version of Quake into a fast-paced Call of Duty wannabe. Any time Fortnite tries to add funny new concepts like the Infinity Blade or B.R.U.T.E. Mech, its player base revolts against the perceived threat to the game’s narrower competitiveness. Even Rocket League—a game where rocket-powered cars play soccer—isn’t immune to this kind of skill-based conformity, as Psyonix removed all the non-standard arenas from competitive play when the game’s higher-ranked players loudly complained on the game’s forums.

Battlefield fell victim to this trend. 2011’s Battlefield 3 marks the beginning of this shift towards a faster-paced, more competitive attitude for the series, one that was markedly trying to steal Call of Duty’s players. Battlefield 4 reeled that in a little bit, focusing more on the vehicles and the series’ sandbox elements. But Battlefield 1, which actually did manage to attract new players against Infinite Warfare in 2016, introduced some of the most Call of Duty–style movement in the series, letting players slide into cover and mantle over walls. Battlefield V leaned in further by eliminating the speed penalty after a slide, letting players parkour across rooftops, removing active spotting, and making time-to-kill incredibly fast—a quality in console shooters popularized by its biggest competitor.

Credit: EA

I think it’s safe to say that Battlefield V is—even after its weapon balance changes in December—the most competitive, “skill-based” game in the series. It’s also earned one of the worst reputations of any Battlefield title, at least at the moment. I’m not saying those two things are entirely correlated, but I do think that it has something to do with the reason why some longtime fans of the series have stopped playing altogether.

Namely, the series as a competitive shooter is now almost unrecognizable.

Not one person in my personal Gold Squad—Nick, Bryan, Mason and myself—had a positive kill-death ratio by the end of our Bad Company 2 careers. A decade ago, it wasn’t about getting the most kills or being the best players. It was about infiltrating the bases, moving up the map, or simply holding a position against an angry Hind pilot. We’d spawn in, move up the map, die, respawn. Grab a jeep or a four-wheeler, bomb into a point, die, respawn. Take a transport chopper, get shot down over the first sector in Isla Inocentes, die, respawn.

Somehow, through sheer perseverance and teamwork, we’d arm the MCOM stations and secure the objective enough times to quite often get that coveted Gold Squad pin. We were competitive without even trying. We were just having a good time.

This was the golden age of gaming for me, the moment in time against which I measure every other gaming moment. When I’d think about Bad Company 2, before I started playing it again in 2020, I wouldn’t remember the mechanics or what weapons I’d use. I’d remember the specific escapades with the Gold Squad. Skittering across the oil pipes on Port Valdez while the base on the hill loomed in the distance. Nick and I giving Bryan and Mason chopper support while they hit the first island on Inocentes from a boat with a grenade launcher. The four of us all shooting tracer darts at a chopper until Bryan inevitably got bored and tagged each one of us in the face with it, leaving a blurry red spot in the middle of our screens. Later, in the game’s Vietnam expansion, it was sneaking through the opening jungle on Hill 137 or getting stuck on the bend of the road that led to the bombed out bridge on Cao Son Temple.

Credit: EA

But it wasn’t just the game itself that made this Bad Company 2 era special. Through it, I’d solidified friendships that would last the rest of my life. I’d found a group that accepted me. I felt like part of something bigger.

At some point in 2011, it all fell apart. I won’t blame it entirely on Battlefield 3, but that was the start. The long-awaited “core series” sequel was way faster than Bad Company 2 and way deadlier. Players could go prone and hide behind walls that would have previously been too low to cover them. Rush was less of a priority, which meant that the maps weren’t designed for the mode (though some of them, like Damavand Peak, still shone). At least on Xbox 360, it was much messier, much more competitive experience.

Our real-world relationships, too, had their own friction. I started dating someone who wasn’t into my weed-smoking, gaming-heavy lifestyle. In retrospect, I don’t blame her, but we probably shouldn’t have been together at all. Still, I couldn’t see that at the time, and I let the relationship take precedence over my friends. Then Mason moved to L.A. Bryan moved to Florida. Nick stopped trying. It was the darkest possible timeline.

Eventually, a year later, that relationship had run its course, and I tried to mend the bridges I’d burned. Thankfully, Grand Theft Auto V’s multiplayer had come out, so we moved from Arica Harbor to Los Santos and slowly rebuilt the kind of trust that a Gold Squad needs to survive. We wouldn’t play a Battlefield game again until 2014 or so, when we all got Xbox Ones and Battlefield 4. While that’s still one of the best games in the series, it just wasn’t the same.

Rumors about Bad Company 3 have been floating around since 2014, though then-DICE CEO Karl-Magnus Troedsson admitted to Eurogamer that the studio didn’t fully understand what made Bad Company 2 so special.

What made the game’s single-player campaign so good was easy to understand, Troedsson said. “But some people say this: the Bad Company 2 multiplayer is the best you’ve ever done. Okay, why is that? It’s hard for people to articulate what that is, which is actually hard for us. It would be hard to remake something like that. Can we do it? Of course. We have our theories when it comes to the multiplayer.”

There is some indescribable quality about Bad Company 2. The game specifically engineered the most nebulous, subjective quality in a game: fun. But how do you engineer fun?

Credit: EA

Six years later, it’s a lot easier to answer that question in the context of the games in the series that have come out since.

Going back to play Bad Company 2 in 2020, there are design decisions that really stand out as promoting fun, balanced gameplay.

Credit: EA

The most obvious is the map design. Building maps around the more linear Rush might seem counterintuitive to Battlefield’s identity as an open-ended, sandbox franchise. But what it allowed the designers to do was more carefully curate the moments of engagement, the flow of the action, and the lanes of approach. As linear as the map design is compared to the most current games in the series, I don’t feel limited when I play Bad Company 2 now. If going down the middle of the road on Arica Harbor with a tank isn’t working, I can use the rocks on the outside of the map as cover to more stealthily approach the objective. If snipers are watching me from the mountains on the opposite side, then I take to the mountains. Or I can just bomb down the middle on a four-wheeler, bust through the fences behind the point, and wait for my squad to spawn in so we can set up a strong flank.

Team sizes play into this. On Xbox, Rush is maxed out at 24 players, hitting that perfect balance between having enough space while also creating that chaotic, cinematic war-movie tone. Compare that to Battlefield V’s 64-player Breakthrough, in which players are meant to be massacred in droves, and you can see how the smaller team sizes benefit the gameplay: When you’re one of 12 players, what you do in a match matters significantly more.

Credit: EA

Then there’s the player movement. In Battlefield V, your World War II soldier is basically a freerunner who can run, slide, then jump out of the slide and keep running. Bad Company 2’s soldiers felt like actual soldiers weighted down with metal and kevlar. Players now, who are used to games like Apex Legends or Call of Duty, might call this movement “slow” or “clunky,” but I think the best word for it is considerate. It’s more about picking the right moments, getting in the right positions, and sticking to cover than it is about out-strafing your opponent. Feeling your soldier’s weight also means you feel like you’re stuck in the battle. It creates an immersion that no 4K, 60 fps console game can match.

Most importantly, there’s the gunplay, which remains my favorite in the series. The guns in Bad Company 2 kicked like crazy, and there wasn’t anything you could attach to your gun that would really help with that other than a specialization that you’d have to pick over other, more useful specializations like the lightweight pack or extra armor. Instead, tap or small-burst firing was the key to hitting those long-range targets. Yes, there was spread and weapon bloom, but you counteracted that by knowing the limits of your weapon. It also meant that mid-range battles had time to progress, to ebb and flow. Again, this created immersion.

According to then-senior producer Patrick Bach, DICE maxed out at 70 to 75 developers working on Bad Company 2. It’s possible that there were many more at DICE working on Battlefield 3 at the time, but the smaller team size allowed the studio to “get more focused, you get better traction, and you have high quality if you have the right people. We talk about ownership a lot—owning the quality in the end.” With several longtime developers exiting DICE, it makes one wonder if the developers at that studio are now lacking that sense of ownership as Battlefield V struggles to maintain enthusiasm. With so many different voices wanting so many different things, there’s something to be said about a core group of developers who all share the same vision. That could have something to do with Bad Company 2’s multiplayer success, too: It had a real, palpable vision.

Credit: EA

So far, I’ve convinced Nick, Bryan, and Mason to all reinstall Bad Company 2. We haven’t all had the chance to play together again, but I’m hoping we will soon. I’m not really drinking or smoking anymore, but I am still gaming with the squad.

I’ve also convinced my friend John, who just bought his first Xbox in 2017 and got into Battlefield with Battlefield 1, to give Bad Company 2 a try. It’s literally five bucks on the Xbox Store, and another five if you want the game’s awesome co-op mode, Onslaught.

John’s taste in games ranges from survival-horror to Rainbow Six Siege. When we play together lately, we’ve been playing Red Dead Online, taking leisurely horse rides across the countryside, sometimes taking on bounties, but generally just riding and hunting. Either that or we’re playing Friday the 13th: The Game, which requires a different kind of skill, but it’s mostly just a fun diversion for us. That’s the kind of player John is.

Having only ever played the two most recent Battlefield games, I was curious to see what John would think of my dear Bad Company 2.

“I can’t believe how heavy the soldiers feel,” he said without any prompting. “And the guns actually feel like guns.” This coming from a country boy and responsible gun owner.

“That was so fun,” he said, almost unbelieving, after he and I destroyed most of the MCOMs on Arica Harbor after a particularly intense round. “That was… just so much fun.”

I don’t know if there will ever be a game like Battlefield: Bad Company 2 again, let alone a Battlefield game like Bad Company 2. Meanwhile, it lives on in spirit: when I’m sailing a brigantine in Sea of Thieves with Mason and Bryan, or playing unranked Doubles in Rocket League with Nick, or running from a serial killer in a hockey mask with John. We aren’t competing. We’re just having fun.

Michael Goroff has written and edited for EGM since 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @gogogoroff.