Apart from the extra years he wears on his face, Billy Mitchell looks as though nothing has changed. The man once honored as gaming’s “Player of the Century” still dresses in the same tailored suits and kitsch American flag ties he did when he won the award in 1999. His sculpted, jet-black hair still manages to evoke a mullet while meeting none of the definitional criteria, somehow business everywhere, party everywhere. He still towers over a crowd, still commands a room like he knows he’s the baddest man in it. He remains what he has been for decades in documentaries, interviews, and fan encounters: an avatar of himself.

But this aura of continuity belies the upheaval in Mitchell’s recent past. Last year, Twin Galaxies, the video game record keeping organization with which he built his legacy, branded him a cheater, removed his scores, and barred him from all future submissions. Guinness World Records quickly followed suit. At the heart of the controversy are three of Mitchell’s scores in the arcade classic Donkey Kong. According to multiple independent technical analyses, the available footage indicates at least two of the games were not played on genuine arcade hardware, which would make them, at best, ineligible for submission.

Mitchell has denied, and continues to deny, any and all wrongdoing. Earlier this month, a law firm operating on his behalf sent a demand letter to both Twin Galaxies owner Jace Hall and Guinness threatening legal action unless his scores were reinstated and a retraction published. Accompanying the letter was a 156-page document intended to discredit the claims against him. Just days ago, Twin Galaxies issued its formal response, stating the organization has reviewed Mitchell’s evidence package and will not take any steps to reverse its decision.

Regardless of the outcome, some measure of damage has already been done. Speak with Mitchell or anyone in his orbit, and you soon realize that it’s no longer possible to separate the man from the allegations. The questions “Who is Billy Mitchell?” and “Did he cheat?” are entangled now. You cannot answer one without confronting the other.

This idea is not my invention. During an introductory phone call, Mitchell talked at length about his belief that real journalism no longer exists, that reporters everywhere have been unable to do the research necessary to get to the truth. When I told an ally of Mitchell, the YouTuber and esports team owner TriForce Johnson, that I didn’t want to spend too much time relitigating the scandal and instead wanted to focus on a more human angle, he cautioned me against that approach, comparing Mitchell to Superman.

“No one gives a shit about Clark Kent’s life, because there’s nothing there. He’s married,” Johnson said, now referring to Mitchell. “He has kids. He goes, he works in his family’s hot sauce [company]. You’re going to get all that. But if you think that there’s something else more under that, that’s like, no, there isn’t.” The persona as a gaming superhero—and the ruling that threatens to destroy it—are what matter.

That’s the story I ultimately chased, across countless hours of research and lengthy interviews with Mitchell and nearly two dozen individuals close to him or to the dispute, some of whom have never spoken to the press on this topic.

The staunchness of his defenders and detractors alike means the two sides are unlikely to ever agree on a single version of the truth, barring an outright confession or similarly earthshaking revelation that proves his innocence. Mitchell’s biography, then, has become fractured, perhaps irreparably so. From the early 2000s onward, his life now plays out in two parallel narratives, each with proponents willing to corroborate the most improbable aspects. Each version relies on the existence of an elaborate conspiracy, either for or against Mitchell. The combined picture brims with bizarre details: a bag full of spiders, several thousand clams, flat Earthers, the lead singer of Dashboard Confessional.

The two sides of this story are not equally plausible. But both halves, taken together, tell you far more about Billy Mitchell than the truth alone ever could.

I first met Mitchell at the Museum of Pinball, a low-slung mid-century industrial building in the desert city of Banning, California, about 100 miles east of Los Angeles. The cavernous interiors once housed equipment for manufacturing electrical connectors. Now they hold a collection of classic arcade cabinets and row after row of pinball machines, so meticulous in their alignment that they stretch out improbably toward the vanishing point with the precision of a Renaissance painting.

When I entered the lobby, Mitchell was off to the left, sharing a romantic moment with his wife, Evelyn. My first thought, which recurred throughout the day whenever I saw the two of them interact, was how genuinely happy they seemed together.

My second thought, once Mitchell had walked over to greet me, was that he looked exactly how I expected. To meet him is to meet a comic book character, the cartoon image in your head now given flesh, now shaking your hand, now making intense eye contact. You get the sense you’ve suddenly entered a separate universe where he’s the main character, that the rules might be different here. Something in his angles is Manichean.

Mitchell resides in south Florida, but he’d come to Banning to attend a 70th birthday celebration for Walter Day, the man who founded Twin Galaxies in 1981 and ran various incarnations of the organization until 2010. Despite having stepped aside, Day still wears his trademark referee shirt during public appearances and maintains a toehold in the community through a series of trading cards that honor luminaries of gaming past and present. He is one of the many people who believe Mitchell is innocent, a fact he shared with me unprompted seconds after I first met him.

It would be hours before I’d get a chance to ask Mitchell any real questions. There was still a photoshoot to arrange, cake to be cut, and a lengthy trading card ceremony to watch, in which Day would induct dozens of new faces into his collection, many of them in absentia.

But I had already spoken to Mitchell on the phone, a few days prior, about his formative years, the time before his story splintered in two. He recounted his first memories: Standing on the lawn in Massachusetts at age three, asking his father when they were moving to Florida. His birthday party, now down south, looking at his hand as he held up four fingers. A year later, when he held up five. A new high score, perhaps.

Mitchell described his early childhood as “extremely modest.” His father drove a truck for a living, making local deliveries, and his mom worked at a Kmart store. In those days, Mitchell would often wake up after his father had already left for work and go to sleep before he’d returned. In 1974, following a stint at National Airlines, the elder Mitchell acquired Rickey’s Restaurant. Though he initially had to sell real estate on the side to help pay the bills, Mitchell’s father would turn the restaurant into a success, bolstered by the popularity of its Buffalo-style chicken wings. Rickey’s, Mitchell told me, was just the second restaurant in all of Florida to serve the dish.

The first game Mitchell fell in love with was pinball. “I was just hardcore,” he told me. “I mean, I wanted to win.” He was slow to warm up to video games, even as arcades started sprouting up and attracting the other kids in droves. “I’m the kind of guy that doesn’t like change easily,” he said.

In the end, though, he couldn’t resist. Mitchell started playing Pac-Man and Donkey Kong, and soon bonded with an outcast at school over a shared love of the gaming. In school, this other boy was a nobody, a nerd, picked on by his classmates. But in the arcade, he was in control, demonstrating his mastery of every game. “He was a totally different person,” Mitchell said.

The two of them would compete back and forth, setting higher and higher Donkey Kong scores, with Mitchell always struggling to keep up. He credits this rivalry, in part, with sparking his obsession with chasing high scores. When his friend put up a score of 234,000 and Mitchell, on a particularly strong run, only managed 232,000, he got angry. And then he got better. His scores started to climb. From 232,000 to 258,000, and then all the way to 597,000.

From here, the Book of Mitchell enters its most well-worn chapters: Calling around to see if anyone knew the world record. Finding Twin Galaxies, then a brick-and-mortar arcade in Ottumwa, Iowa. Hearing about some kid named Steve Sanders who claimed he’d notched 1.4 million. Traveling to Ottumwa for the Life magazine photoshoot in November of 1982. Meeting with the other early icons of arcade gaming. Calling Sanders’ bluff in Donkey Kong. Reaching the “kill screen”—level 22, when a bug in the program causes the game to end. Earning a score of 874,300, a record that would stand for more than 18 years.

Seeing Twin Galaxies in person for the first time, Mitchell was surprised. “The arcade was not what I expected. Remember, I came from the world’s largest arcade in Fort Lauderdale,” he said. His home turf was Grand Prix Race-O-Rama, a sprawling entertainment center that in its heyday boasted upwards of 1,000 arcade machines. For the biggest new releases, Grand Prix would have entire rows of the same game, each with a line waiting to play. By comparison, Twin Galaxies was “a little hole in the wall.”

Tim McVey, the world record holder in Nibbler and subject of the 2015 documentary Man vs. Snake, grew up in Ottumwa and became a regular in the Twin Galaxies scene, though it was his cousin, not him, that appeared in the Life photoshoot. McVey told me reactions like Mitchell’s were common. “You read some people talking about it and it’s like they thought you were walking into this Walmart- or this mall-sized arcade, and it was just this little itty bitty arcade,” he said. “They only had 22 or 24 titles in there. You know, it wasn’t very big. It was just not that big ever, and it’s always seemed bigger than what it was on paper and in brick.”

Around this time, Mitchell first met Robert Childs, a man who would become his lifelong friend and, much later, play a pivotal role in the score dispute. Childs got his start working on classic games at the age of six, he told me, tinkering in a Maryland arcade run by his father, a doctor and dentist, as a side business. When the family moved to Florida in his early teens, Childs started his own business, buying cabinets and installing them in public venues like laundromats. Today he runs a store called Arcade Game Sales just north of Fort Lauderdale.

By the time they met, Childs was already aware of Mitchell’s reputation in the gaming world, since his accomplishments had made him something of a hometown hero. “Different friends I knew were like, ‘Oh, have you ever heard about that Billy Mitchell?’” Childs said. When the two met over a potential business deal, they hit it off, and Childs became a close friend of the family and a fixture at Rickey’s, where he perpetrated a one-man war against bivalves.

“I went to his restaurant, oh, 125 times in a row and ate and, you know, he never charged me,” Childs recalled. “I’m not kidding. Every single night I went to his restaurant.” He told me his standard order was clam chowder and clams. “I would order four or five dozen steamed clams at a time, and I was young back then. I didn’t have any money.”

In the summer of 1983, Mitchell and other top players reunited with Day to participate in a new venture: the Electronic Circus. The brainchild of businessman Jim Riley, the circus was to travel around the country on a 40-city tour, bringing with it a huge selection of arcade games, attractions, and “superstar” players.

“It failed in about four days,” Mitchell said.

In the aftermath, Mitchell and some of the players, who’d expected a salary for their work on the Electronic Circus, found it hard to let go of the dream. “There was a group of us who didn’t want to go back home. We were hardcore players. So we went back to Ottumwa with Walter,” Mitchell told me. “We slept on the arcade floor in the back storage area. We woke up, we played games all day into the night, went back to sleep. And it went on throughout the rest of the summer.”

McVey recalled Mitchell standing out among that early Twin Galaxies crowd. “All the rest of us would play everything. When a new game came out, we would try the new game. We’d want to be the first person to kind of master it,” he said. “Well, not Billy. Billy just seemed to focus on one thing and just fixate on it and just really play the crap out of it.”

In total, Mitchell only ever played six games competitively: BurgerTime, Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., Pac-Man, Ms. Pac-Man, and Centipede. That fact that all these games are still well known today is no accident. “Nobody would hear about me if I was playing Bomb Jack,” Mitchell told me.

In late July, Day organized the U.S. National Video Game Team, made up of Mitchell and other top players. The group piled onto a 44-foot bus full of arcade games to tour the country, intending to visit at least one city in each state.

Mitchell’s stories from this trip read like a comedy of errors: a breakdown in Wisconsin, running out of gas in the Midwest, a break-in and theft in Omaha. At this point, Mitchell told me, the group abandoned the bus for a rental car and made it to the West Coast, heading down to San Diego, with stops at Nintendo and Sega along the way. Mitchell and the team headed back east towards Dallas—only to have the car break down in the Arizona desert, where they were stranded for hours. Eventually, a good Samaritan stopped and, as luck would have it, her husband was a mechanic. He repaired the car, and in exchange, Mitchell said, the gamers gave the family some of the gifts they’d gotten on their trip, including then-unreleased products from Nintendo and Sega. Finally back on the road, the team made it a whole 10 minutes before the engine failed again, forcing another rescue, this time by a passing police officer.

You’d think the experience might have soured Mitchell on cross-country voyages. Not so. Later that year, Walter Day flew down to Florida and convinced Mitchell’s father to let him come along for some promotions. Day and Mitchell drove up to North Carolina together to make contact with a potential champion.

“There was a particular player there who claimed a particular score on Ms. Pac-Man that we just didn’t believe. And when it came time for the guy to be there and play, he’s there and he’s got his arm in a sling, so he hurt himself. He can’t play. Give me a break,” Mitchell said. “I didn’t do anything, but eventually some guys grabbed him and pulled the sling off and made him play, and he didn’t do too good.”

As it turned out, quite a few of Mitchell’s travels with Day would involve debunking bogus scores. Tim McVey told me these sorts of shenanigans were a surprise to the early gamers. “Walter, at the time, when he was starting the scoreboard… he never considered that people were going to lie and cheat. And at the time, I think a lot of us probably didn’t. I mean, why in hell would you?” he said.

Another trip brought Mitchell to New Jersey, to visit someone who’d claimed 11 million on Donkey Kong. “Before we could even question his score, it suddenly appeared in a magazine again, and this time it was 13 million.” Mitchell said he spoke to this Donkey Kong guru on the phone and told him he and Day were coming to visit. “And the guy changed his phone number. Later on, somebody said he moved away.”

In January of 1984, Twin Galaxies crowned Mitchell player of the year at an event in Ottumwa, but it would be the last time he’d ever set foot inside the arcade. The physical location shut down in March of that year, one of the many arcades that would shutter throughout the mid-’80s as the gaming boom died down.

One thing you quickly notice in speaking to Mitchell is that he is a devoted scholar of his own legend. During our conversations, I found myself recognizing his answers, sometimes down to specific phrases, from other interviews I’d read or watched during my research. This is not the most desirable quality in an interview subject, but it did provide support for a topic he raised a few times throughout our conversations: that he has a superior memory.

During one such instance, he recounted a story about a Jehovah’s Witness who came to his door early one morning after a late night of work. To show the woman he wasn’t in need of any spiritual guidance, he’d rattled off all of the books of the New Testament in order. She left. He went back to sleep. As if to prove his point, he recited the list on our phone call, too, in less than 10 seconds. Occasionally, he’d bring up his specific scores or those of other players from the ’80s, and while these weren’t always digit-perfect when I later checked them against official records, they were close enough to impress.

Mitchell’s recall does not appear to be limited to simple facts and figures. He’d sometimes bring up scenes from his past and grow quiet, as though he was lost in a moment I would never be privy to. This was when he seemed the least guarded. “You know the first time my daughter was out in the rain, you know, the raindrops hitting her in the face and all that…” His voice trailed off. “It can be a lot of fun to have such a good memory. It can be annoying, too, but, you know, it can be a lot of fun.”

The closure of the Twin Galaxies arcade also marked the end of an era for Mitchell. His BurgerTime record of 7.8 million, entered in 1985, would be his last for more than a decade as he stepped back from the world of arcade gaming. During this period, he involved himself more closely with Rickey’s and eventually assumed control of the hot sauce business that spun out of it.

“I can’t play video games my whole life,” Mitchell said, recalling his thinking at the time. “I know I have to be a real person with a real passion, a real career. And I took that passion, that stubbornness, that competitiveness, that burning desire to be the best, and I turned it inward on our family business. And I began a hardcore, really hardcore push, you know, towards everything that that is.”

It would be nearly 15 years before he would return to claim a new record. The game that would eventually drag him back wasn’t Donkey Kong, but Pac-Man.

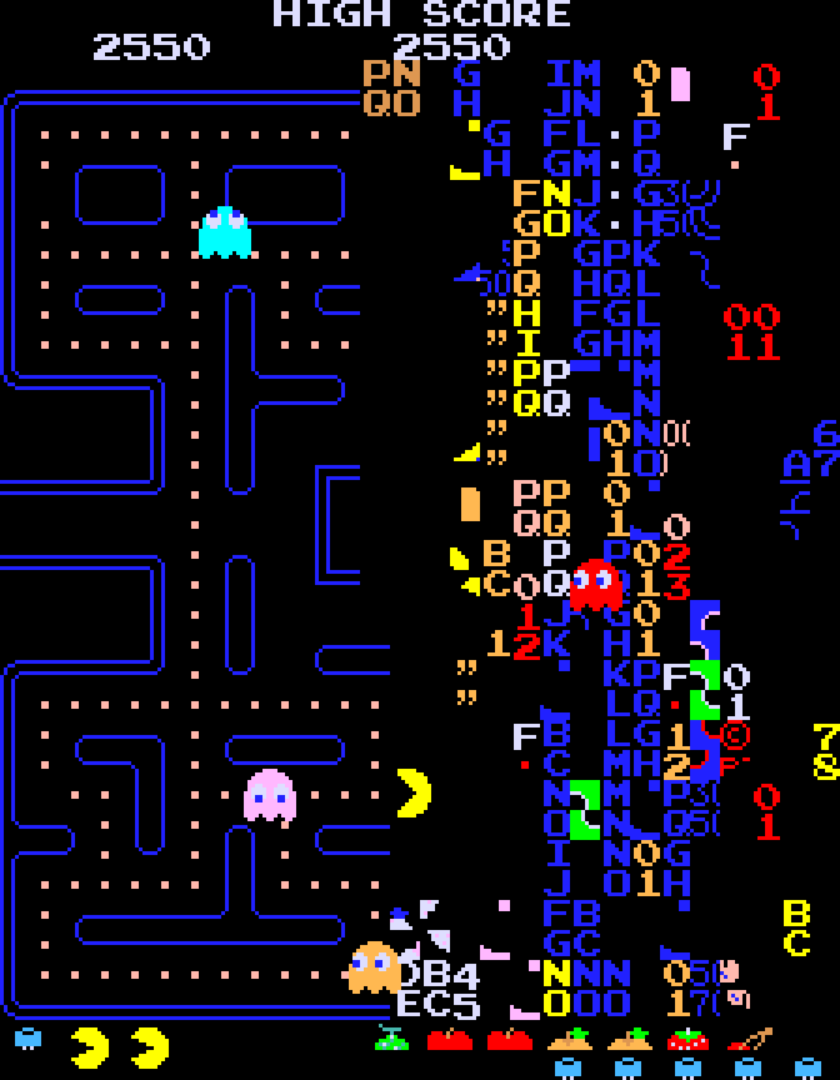

For 255 levels, Pac-Man is, in some sense, perfect. Its maze, with layout unchanged across each screen, features no dead ends. The outer border breaks only to fold back upon itself, with two tunnels that instantly transport Pac-Man and any ghosts who enter to the opposite side. Each dot or fruit or ghost that Pac-Man eats always grants the same number of points. The four ghosts—Blinky, Pinky, Inky, and Clyde—all follow their own distinct but fixed rules of motion. Their chase grows faster and faster as the levels increment but is always governed by clear, immutable laws, rules that allow a skilled player to herd the pursuers into formation. In Pac-Man there is no room for the stochastic. Any given input will yield a known output. The Ancient Greeks might have called it a kosmos, an ordered and self-contained universe made beautiful by the total intelligibility it offers any sufficiently dedicated theorist.

Then, upon reaching level 256, a cascade of programmatic misunderstandings throw this perfection into chaos. The level counter in the game’s memory, having already filled its eight allotted binary digits, flips all the ones to zeros. The code that draws fruit and bells and keys in the bottom right corner of the screen—a simplistic level indicator—now believes it must draw 256 such icons. Without sufficient space to do so, the images first begin to overlap, then spill over onto the maze above. Once the game expends the 20 icons defined in the code, it starts to take graphical cues from unrelated data, tossing numbers, letters, pieces of walls into the mix. By the time the program fills its accidental quota, just over half the screen is nonsense. On the left, the old and beautiful order remains intact. On the right, madness.

This is the end of Pac-Man’s universe. The rules can no longer keep themselves. This is the “split screen,” the impassable barrier that caps what even the most adept Pac-Man players will ever achieve on original arcade hardware without cheating.

Credit: Bandai Namco, via the author

Mitchell told me he first saw the split screen in 1983, though he does not claim to have discovered it. He’d already heard stories of this strange frontier by the time he and a friend, Chris Ayra, set to work reaching it. “We wanted to play it, and we had learned the proper patterns to do it,” he said. “A couple times we crashed and burned because we simply weren’t paying attention the way we should, but we did it collectively, me and [Ayra], just trading off just to want to get there and see it.”

McVey remembers seeing the pair play for hours trying to reach the split screen, and once they got there, attempting to discover its secrets. “They surmised that they couldn’t clear the screen because they couldn’t eat enough dots to get the total required,” he said.

The code Pac-Man uses to determine when to advance to the next level is simple: When Pac-Man has eaten 244 dots, the level ends. The mangled split screen simply doesn’t have that many. “So they were playing through the scrambled computer language stuff on the right side trying to figure out you know, if there’s more dots over there that you could eat to possibly advance past it,” McVey recalled.

As it turns out, there are dots scattered across the right side, some visible, some invisible, but at just nine, they’re too few to make up the difference. Unlike normal dots, these nine regenerate upon death. If you make it to the split screen with extra lives intact, you can eat these glitched dots multiple times to bump your score slightly higher. Reach the end with five lives—the maximum allowed by unmodified arcade hardware—and pick up all nine dots each life, and you can set the highest score possible: 3,333,360.

Mitchell has said he and Ayra developed the theoretical knowledge to achieve a perfect score in ’83, placing a paper over the split screen so they could map out the dots and invisible walls. They developed a method for trapping three of the ghosts along the right side of the screen to minimize risk, as well. Mitchell wouldn’t tell me whether he’d actually attained a perfect score back then or at any point during the ’80s. Even if he had, he said, it wouldn’t count for anything, since he wouldn’t have done it at an official event.

In 1999, Mitchell caught wind that a group of Canadians, including a player named Rick Fothergill, were closing in on attaining a perfect Pac-Man score. Determined to beat them to the punch, he started training for a return to the gaming world. Though Fothergill came one life short of earning the title that May, Mitchell ultimately prevailed on July 3rd, earning the first officially recognized perfect score at the Funspot arcade in Laconia, New Hampshire.

It’s this achievement that prompted Twin Galaxies to declare Mitchell the “Video Game Player of the Century.” Namco, the company behind Pac-Man, even flew Mitchell to Japan, brought him onstage at the Tokyo Game Show, presented him with a commemorative plaque, and offered him a chance to meet founder Masaya Nakamura.

Despite the wealth of media coverage at the time, I’d never heard of Billy Mitchell or his perfect Pac-Man score until years after the fact. Like most, I first encountered Mitchell in The King of Kong, a 2007 documentary that framed itself around the rivalry between Mitchell and Washington schoolteacher Steve Wiebe to set a new record in Donkey Kong.

Mitchell has repeatedly referred to the movie as a work of fiction, stating that elements were deceptively edited or outright staged in service of establishing a narrative with a clear hero and villain. Most of the individuals I spoke with who participated in the film or knew its subjects, including those who question Mitchell’s scores today, agreed that many aspects of The King of Kong were heavily exaggerated or misleading. They were split, however, on whether the film accurately portrayed the personalities of those involved.

In any case, it’s the many memorable scenes in this film that established Billy Mitchell’s reputation as the black hat of the gaming world. When he answers the phone by saying, “World record headquarters.” (Staged, Mitchell has said.) When he walks in on Wiebe playing, looks on icily, and leaves without saying a word. (All editing, according to Mitchell.) Evilest of all, when Mitchell refuses to come to the 2005 Funspot event to compete in person but instead sends a previously recorded tape. As Wiebe sits at his cabinet, attempting to break 1 million points live, attendees set up a VCR in the arcade and watch as Mitchell, on tape, smashes through that milestone, ultimately finishing his game at 1,047,200.

This score, commonly referred to as the “King of Kong tape” is one of two performances Twin Galaxies eventually cited as grounds for its decision to remove all of Mitchell’s scores. The second score—1,050,200, known as the Mortgage Brokers score—was set at at a July 2007 convention of the Florida Association of Mortgage Brokers in Orlando. For this attempt, Mitchell sought to make the score unimpeachable by sending the Donkey Kong circuit board to Nintendo for verification, and then having a local GameStop manager install and lock it into the cabinet before he ever arrived at the venue.

But it’s a third score, one for which Twin Galaxies declined to issue a final ruling, that first ignited the investigation. This record—1,062,800, called the Boomers score—took place on Saturday, July 31st, 2010, at Boomers in Dania, Florida, the same arcade that had once been Grand Prix Race-O-Rama. In honor of the opening of the International Video Game Hall of Fame, Mitchell set two records that day, in both Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. It was an impressive feat of showmanship in a field where any single record is usually only obtained after countless failed attempts. He announced the scores publicly the following weekend, at an event in Ottumwa called Big Bang 2010. Footage of this announcement shows Mitchell standing beside two TVs displaying both records, but only a small portion of the hours of gameplay is visible.

On August 28th, 2017, Jeremy Young opened a dispute thread against Mitchell on the Twin Galaxies forums. Young, a moderator of the Donkey Kong Forums, wanted to draw the community’s attention to a strange YouTube video ostensibly recorded the day of the Boomers attempt, when Mitchell achieved his final record in Donkey Kong.

The video that caught Young’s eye was uploaded by Mitchell’s longtime friend, Robert Childs, and purported to show Childs swapping out the circuit boards containing each game between the score attempts. (This way Mitchell could play both games on a single arcade cabinet.) What members of the community had noticed, however, is that the video only shows a single board, for Donkey Kong Jr. Childs removes the Jr. board and then reinstalls it, with the camera panning away in between to disguise that fact.

Mitchell and Childs now admit this video was staged. They’ve said it was created purely to help Childs boost his channel, and that is was recorded at the end of the day, after the records had already been broken. By this point, they claim, Childs had loaded the Donkey Kong board into his car and was too lazy to go get it.

If that had been the whole of the evidence, the controversy might have ended there. The current Twin Galaxies dispute system relies on votes from the community in the early stages of any decision. When enough members vote that a dispute is valid by a high enough margin, Twin Galaxies administrators review the case and render a final verdict. But a dispute based on thin evidence or one that doesn’t garner enough interest might stay in limbo forever.

In February of 2018, however, Jeremy Young relayed new findings on Mitchell’s scores that alleged something far more serious and difficult to ignore. Young put forth specific technical evidence intended to show that the King of Kong tape, the Mortgage Brokers score, and the Boomers score were played not on genuine arcade hardware—as Mitchell claimed and the rules required—but on MAME, a program for emulating classic arcade games on PC. Just like that, Mitchell’s three highest Donkey Kong scores—the only times he’d officially broken 1 million points—were on trial. Within three months they’d be gone from the scoreboard.

When they were first accepted into the Twin Galaxies database, all three of these scores were world records, though they have since been surpassed by a considerable margin. (John McCurdy of Pennsylvania set the current record of 1,259,000 in May, streaming live on Twitch.) Only the first of these, the King of Kong score, which Mitchell maintains he never put forward as an official submission, used a tape recording for verification purposes. For the other two scores, Mitchell relied on a Twin Galaxies policy that allowed referees to verify any scores they witnessed live.

In both cases, the referee was Todd Rogers, a longtime player in the classic gaming world who looks and dresses as though someone has fused 1990s Ron Jeremy with 1990s Steven Seagal. In January 2018, in a move that prefigured Mitchell’s case, Twin Galaxies threw out Rogers’ scores following a technical analysis by the community that determined his long-standing record in the Atari game Dragster was impossible, as well as testimony that he had entered a suspiciously large number of his own scores into the database. Rogers maintains that he was not the only Twin Galaxies referee to enter his own scores and that he did, in fact, obtain the seemingly impossible Dragster score on multiple occasions. In 2017, the game’s designer, Activision co-founder David Crane, told Kotaku he believed Rogers but did not have proof.

While the Boomers and Mortgage Brokers scores relied on Rogers as referee, Mitchell did capture gameplay of these records and told me he submitted them to Twin Galaxies—for entertainment purposes, he said—along with other supporting evidence, such as secondary recordings that show the wider play area. None of the room tapes have surfaced during the course of the dispute, nor have the tapes of the Boomers attempts, beyond the offscreen footage from Big Bang. Mitchell has said he does not have personal copies of any of these scores, something the other arcade competitors I spoke with characterized as extremely unusual.

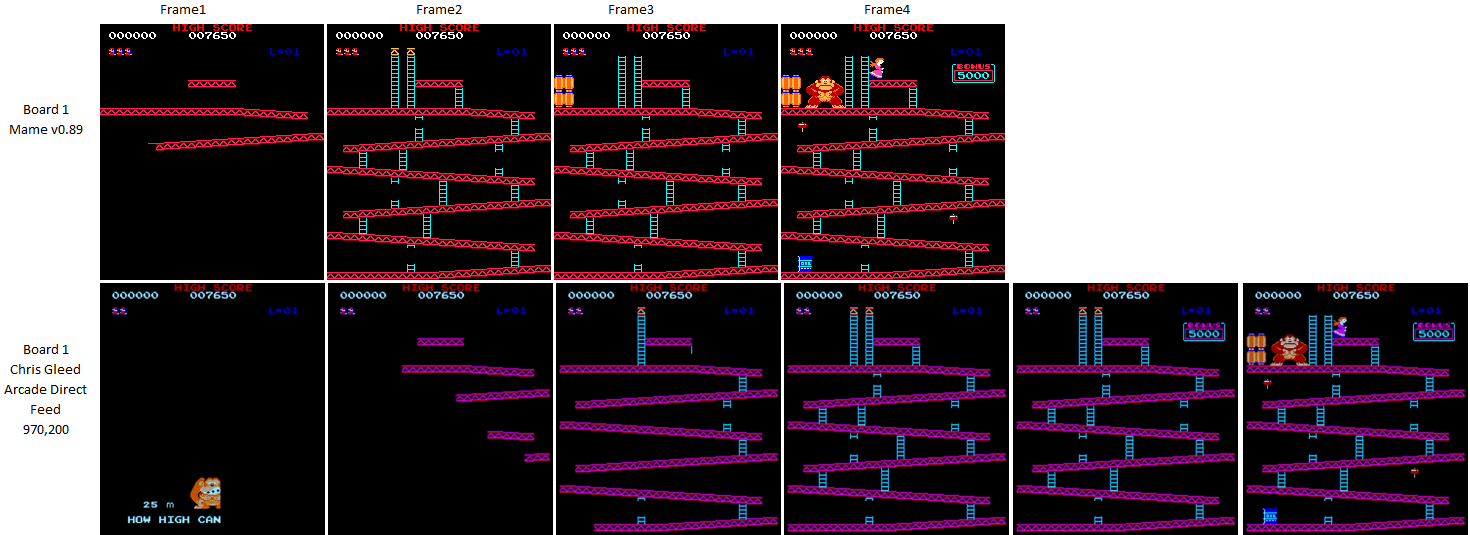

The Twin Galaxies decision against Mitchell relied on analysis of the recordings that did survive. The simplest and most useful way to understand the technical evidence is to focus on two key features of the recordings for which testing has been unable to provide any clear explanation: the screen orientation and the three-girder pattern.

1.05 million (above)

and 1.047 million tapes.

Credit: Nintendo via

Billy Mitchell, Jeremy Young

The first, the orientation, is straightforward. The footage of two of Mitchell’s disputed Donkey Kong records, in the currently available videos and earlier offscreen recordings, showcases gameplay rotated 180 degrees from the way it would appear on a standard direct feed setup—that is, from a video capture device connected directly to the arcade board, which Mitchell and Robert Childs say they used. Since Donkey Kong, like many arcade cabinets, uses a monitor that’s been rotated on its side to display a vertical image, when you capture the video signal and play it back on a standard TV or monitor, the top of the image is normally on the right side of the display. On two of Mitchell’s tapes, the top of the image is on the left. (The surviving footage of the Boomers attempt is oriented correctly.) Carlos Pineiro, a former arcade technician who conducted testing on behalf of Mitchell during the dispute, told me it would be impossible to produce recordings with this incorrect orientation using the capture setup Childs described to him, barring a modification to the arcade hardware that would itself disqualify any score attempt.

The second feature, the three-girder pattern, requires a bit more explanation. It refers to a quirk of how Donkey Kong loads in one of its four level types. On the so-called “barrel boards,” Mario must leap over barrels and climb up slanted construction girders to rescue Pauline. If you scrub through video captured directly from a Donkey Kong arcade cabinet frame by frame, when a barrel board loads in, you’ll notice that portions of the top five girders all pop into existence in the same instant. In the existing footage of Mitchell’s records, over and over again, a different pattern occurs. Only portions of the top three girders are visible in that first frame.

This pattern, as noted by Jeremy Young in his forum posts, is visually identical to one produced by some versions of MAME. Twin Galaxies never concluded outright that Mitchell’s scores were played on MAME. Carlos Pineiro’s official report does not mention MAME at all, at his own insistence, but he told me that he took time to test versions of MAME that were available at the time the tapes would have been produced, and was quickly able to create a perfect match. He said he still has recordings of these tests. MAME would also offer an easy explanation for the rotated image. With the emulator, Pineiro told me, the difference between the correct and incorrect orientation is a menu setting or a single slash in the configuration file.

On April 12th, 2018, Twin Galaxies ruled that the first two of Mitchell’s disputed scores, the 1.047 million King of Kong score and 1.050 million Mortgage Brokers score, as depicted on the tapes, were not played on genuine arcade hardware. It declined to make a determination on the 1.062 million score from Boomers, citing a lack of direct evidence. The announcement made special mention of that fact that even Carlos Pineiro, who ran tests on behalf of Mitchell, concluded that the games were not played on arcade machines.

Because of a policy that states intentional efforts to mislead Twin Galaxies will result in a lifetime ban, all of Mitchell’s scores were removed, not just those in Donkey Kong. As such, the organization no longer considers him to be the first person to achieve a perfect game of Pac-Man.

Credit: Nintendo via Jeremy Young, Chris Gleed.

In the year that followed, little changed. Mitchell routinely stated during interviews and appearances that he was in the process of gathering evidence that would exonerate him. During this time, he began streaming on Twitch with the help of his son, Billy Jr., eventually obtaining scores equal to those that had been disputed, broadcast live from public venues. (No one I spoke to, not even Jeremy Young, said they had reason to doubt these new games were above board.) Mitchell had proven he could earn those scores now. But he hadn’t outlined a clear defense to prove he’d achieved them at the time of the original submissions.

This was the state of affairs in May, when I arrived in the desert seeking an audience with Billy Mitchell. From the start, I was keenly aware that the members of Team Billy in attendance, of which there were several, viewed me and my motives with suspicion. The skepticism was understandable given the circumstances, but it had the effect of convincing me I had stumbled onto the set of of some exceedingly mundane spy thriller.

I don’t consider myself prone to paranoia, but I thought I sensed that everywhere around me, just out of earshot, members of Mitchell’s entourage were talking about me, conferring, comparing notes on what I’d said to them and what they’d heard from one another.

Before long, TriForce Johnson pulled me aside. He wanted to know if a rumor he’d caught wind of was true. He wanted to know if I had been speaking with Dwayne Richard.

If Dwayne Richard did not exist, I am certain I would be unable to invent him.

We met at a Denny’s in the flavorless L.A. suburb of Hacienda Heights, where Richard had spent the night during a stopover between his home in Canada and a gaming competition in Australia. With his dreadlocks, loose-fitting t-shirt, cargo shorts, and shaggy, unkempt beard, he looked like he’d just wandered out of a Phish concert or a tent at Burning Man. I found it difficult to picture him ever sharing a room with the perpetually well-groomed Mitchell.

Before I had the chance to ask a single question, Richard led me through a series of tangents that the rationalist in me can most charitably describe as “colorful.” The philosopher Bertrand Russell was part of the Illuminati. Science fiction was created as part of a Navy operation. The Moon landing was a hoax. The Earth is flat. A massive culture once occupied Antarctica. The North Pole is actually tropical, but the powers that be won’t let you get close enough to discover that for yourself. Dark matter. Nikola Tesla. Einstein.

“I’ve been working on this stuff for decades, man,” he explained. (He would later inform me via text message that he’d persuaded another classic gamer, who competes in Frogger, of the Earth’s flatness: “He was converted to see things as they are.”)

Richard, who featured prominently in Man vs. Snake alongside Tim McVey, has been a part of the arcade gaming scene since the 1980s. According to the current Twin Galaxies scoreboard, he holds world records in 18 games, in addition to top-10 scores in more than 80 different categories. While many competitors specialize in just a handful of games, Richard is a generalist in the extreme.

This sensibility helps to explain his attitude toward The King of Kong. Like Mitchell, he believes the documentary was heavily fabricated, but he also resents the impact its popularity has had on the classic gaming world. “It just kept the focus on Donkey Kong,” he said. “Like, there’s so many far better games. And this bullshit of Donkey Kong is the hardest game. It’s like, no, it’s not. There’s women that can kill screen it now.”

Richard firmly believes that Billy Mitchell is guilty of fabricating his Donkey Kong scores, and he did not shy away from making direct accusations when we talked. He told me he’d had hunches about Donkey Kong players cheating since the early 2000s, offering a philosophical justification for his ability to spot misconduct. “Tom Asaki and myself,” he said, mentioning another longtime fixture of the arcade community, “we see it like being research artists, physicists, where you’re trying to figure out the cosmology of that world of the video game. And that’s how you know when something isn’t right.”

Richard told me he has not spoken to Mitchell in at least seven years, but he still considers himself “one of Bill’s friends.” Less than 90 seconds earlier, he’d referred to Mitchell as “a straight-up crazy psychopath.” It would appear his feelings are complicated. From my outsider’s perspective, the rift between the two men seems equal parts professional and personal.

Richard confirmed to me that he once registered “fuckbillymitchell.com,” though he no longer has ownership of the domain. At one point, he had unauthorized access to Mitchell’s email account and would log in to read through his messages in front of others, something Mitchell has alleged publicly and Tim McVey told me he witnessed firsthand. Richard also produced two low-budget documentaries assailing Mitchell’s gaming records, The King of Con and The Perfect Fraudman, both of which are available to watch on YouTube. The films attack, among other things, Mitchell’s 1999 perfect Pac-Man score, claiming unsportsmanlike conduct and preferential treatment. This record seems to be a particular sticking point for Richard.

“He actually thinks he has to be perfect,” Richard said of Mitchell. “He’s put himself in a corner using that. You just got the highest score in Pac-Man under certain constraints. That doesn’t mean that you’re a perfect husband, businessman. But he uses that superlative, and so that’s why he shifted from his tight-ass jeans to the suit and the American flag tie. And then he ties in the patriotism and all that. Like, he’s just trying to be this all-American hero.”

But none of this was why I wanted to speak to Richard. I first reached out because his name figures prominently into Mitchell’s defense. In the 156-page evidence package sent to Twin Galaxies and many of his prior statements, Mitchell has held up Richard as one possible explanation for the anomalies in the gameplay recordings. If Richard, as part of some personal vendetta, modified the recordings used by Twin Galaxies, the most important evidence in the dispute would be null and void.

It’s true that Richard directly supplied some of the recordings to Twin Galaxies for the investigation, having originally obtained copies back when he worked with the organization to adjudicate scores. It’s also true that there is no publicly documented chain of custody for the secondary set of recordings provided by Greg Erway, a former Twin Galaxies referee and current world record holder in Tapper and Root Beer Tapper. Erway told me it’s possible his versions might trace back to Richard as well.

Far more damaging, however, is a series of conversations and messages between Richard and other members of the classic gaming community. On multiple occasions, Richard reached out in search of someone who might be able to help him falsify a Donkey Kong score.

In Banning, I heard a direct account of two such conversations from Richie Knucklez, the proprietor of a New Jersey arcade and one of Mitchell’s close friends. Knucklez, whose real last name is Vavrence, held an ownership stake in Twin Galaxies for a brief period starting in 2012 and today organizes a Donkey Kong tournament series called the Kong-Off. (His nickname stems from an incident when his hardcore band was jumped at the Bridgewater Commons mall. In the confusion of the ensuing brawl, he told me, he mistakenly punched a police officer in the face.) The first conversation Knucklez recounted occurred at a group dinner at a Funspot event, which Mitchell’s evidence package dates to 2009.

“He said what we should do, like a group effort, we should take MAME, use save states, get the best possible score on each [Donkey Kong] board, keep playing each board till we get the best possible score, and then string it all together and make a world record,” Knucklez told me. “He didn’t say to put egg on Billy’s face. He said, exact words were, ‘to put egg on Twin Galaxies’ face.’ Exact words.”

Knucklez said Richard later followed up directly by phone, calling him while he was in the parking lot of a White Castle. In this second conversation, Knucklez said, Richard tried to goad him into helping because of his friction with the new owner of Twin Galaxies at the time, a man named Pete Bouvier. “I said, ‘I don’t dislike Pete enough to waste my time doing such a ruse,’” Knucklez recalled, saying he hung up and never spoke to Richard again.

The mention of a Donkey Kong forgery, specifically one created in MAME, is so striking that it’s difficult to dismiss as pure coincidence. Knucklez’s story is further supported by a pair of emails from Richard to Robert Childs in the evidence package. In 2009 Richard asked for a tech who could help “make a score on dkong.” In 2011 he wrote, “billymitchell and his tight fuckin [jeans] I have a master plan to take him down.”

The technicians and Donkey Kong players I spoke to told me it would be absurd, if not impossible, for Richard or anyone else to exactly recreate Mitchell’s entire performances in MAME. More feasible would be tampering with the tapes by inserting just the few frames for the emulated screen transitions, such that they would display the three-girder pattern between legitimate gameplay. But there’s no evidence anyone even knew about the three girders prior to early 2018, and this would, in any case, make for an extraordinarily subtle frame-up.

The most convincing argument against the idea Richard might have doctored the tapes, however, did not emerge until after the verdict. Earlier this year, a member of the Donkey Kong community who goes by the handle ersatz_cats uncovered archived videos of a February 2006 MTV interview with Robert Mruczek, then a senior editor and referee for Twin Galaxies and formerly its chief adjudicator. The videos include footage of one of the three scores, the King of Kong tape. Analysis from the community concluded that this footage matches up with the longer version used during the dispute and even demonstrates the same telltale three-girder pattern. The screen orientation is also incorrect.

Mruczek confirmed to me that Dwayne Richard could not have obtained possession of the King of Kong tape prior to this MTV interview.

More recently, a Twin Galaxies forum member with the username The Evener posted video and photographs from an even earlier event in the U.K., in 2005, where Mitchell and Walter Day appeared in person and a TV displayed the King of Kong tape to attendees. The orientation is incorrect here as well.

The timing of both events predates any documented instance of Richard requesting help with MAME forgeries by years. What’s more, Richard told me when we spoke that he and Mitchell were still on good terms in 2006. While he did suspect cheating in the Donkey Kong community back then, he said his attentions were focused on another prominent player, not Mitchell. And the MAME idea, he said, was just a means to encourage Twin Galaxies to be more vigilant. “I just wanted to show that we need to be more aware of what’s going on.”

At times throughout our conversation, Richard struck me as annoyed, and maybe even a little angry, about his role in all this. More often, he seemed amused. Near the end, however, he slipped into a more regretful, almost elegiac tone.

“This has been a hard thing for all of us in many ways, the fact that we’re not friends and we’re not close anymore like the way we were,” he said. “And all the good times we had, I’d never trade that stuff for anything in the world because it was my life. But the way things are right now, it just, it makes us all sad.… The world’s crept into what was our sanctuary and our safe place, our place to go visit, to time travel into the past, into that netherworld of happiness playing arcade games. It’s just sort of been ruined.”

I couldn’t tell whether Richard recognized that his own actions might have contributed to that decline. One striking truth about entering into this world of competitive arcade gaming, the backbone that only occasionally pokes through in documentaries like Chasing Ghosts, Man vs. Snake, and, of course, The King of Kong, is the sheer amount of interpersonal drama that has accrued over the decades, thick like dust on a neglected arcade cabinet. All these people were once friends, or at least acquaintances, or at least peers. So much of that camaraderie has rotted away.

Steve Kleisath only wanted to help. A world record holder in Mario Bros. and professional drummer—most recently with a band called The Darling Fire—Kleisath had known Mitchell and Robert Childs for years when the dispute first erupted. He’d worked with both of them to organize a regular event called Retro Arcade Night, where they’d charge admission to Childs’ shop and let attendees enjoy the games on free play.

In a 2014 video interview with the New Times Broward-Palm Beach about the event, all three appear on camera together. “It’s promoted by Steve,” Mitchell says. “It’s his vision. He’s constantly working hard at it. He’s constantly building relationships, and the people that you have out there and the fun that it is today is due to him.”

When the Twin Galaxies dispute surfaced, Kleisath thought it was “bullshit” and immediately sided with Mitchell and Childs. “I have no reason not to believe them because I’ve been friends with them for six or seven years,” he told me.

Unlike Kleisath, Carlos Pineiro had never even heard of Billy Mitchell prior to his involvement with the dispute. But he’d met Childs around 2015, when he went into Arcade Game Sales to get rid of an old collection of arcade boards. Pineiro had once dreamed of opening his own arcade, but after years of the boards gathering dust in his garage, he finally decided to part with them—at any price he could get. After the sale, Pineiro added Childs on Facebook but didn’t really keep in touch beyond that.

In early 2018, however, one of Childs’ posts caught his eye. It was a detailed description of a direct feed setup that could be used to record footage from an arcade machine. Since Pineiro had worked for Sega for years on arcade machines, he felt compelled to respond, saying that everything Childs had described was indeed correct. At the time, Pineiro knew nothing of the surrounding context.

Spotting a chance to help, Kleisath reached out and asked if Pineiro might be willing to conduct tests on Mitchell’s behalf, to prove there was an easy explanation for the three-girder phenomenon in the videos. He agreed. “I honestly thought I was only going to take a couple of days,” Pineiro told me.

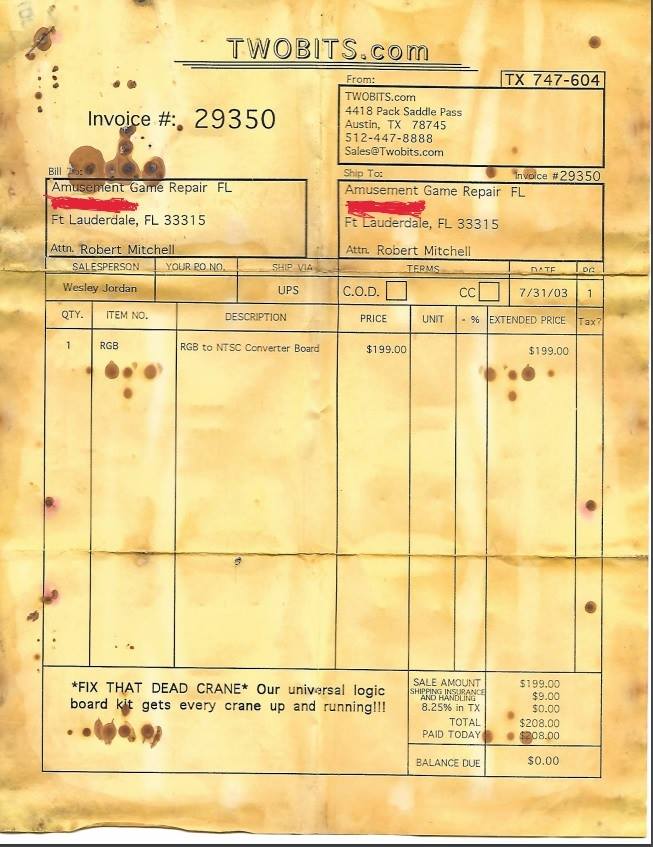

Pineiro and Kleisath set up shop inside of Arcade Game Sales, and Mitchell and Childs provided them with anything they could possibly need throughout the process. They had access to the original video capture devices: a device called a Two-Bit Converter and, for the Boomers score, a USB capture card and laptop that Childs said he used. They even had the exact same Donkey Kong circuit boards, also called PCBs, that Mitchell said he used during the Mortgage Brokers and Boomers attempts. At times, Mitchell himself played for the test recordings. Kleisath was often there to help out however he could, though he told me he lacked the deep technical knowledge required to take a leading role in testing.

“I just started working on it and working on it and recording hours and hours and hours of video. Hours,” Pineiro said. “And watching other players for hours on slow motion, because I’m assuming, all right, this is going to be one of those shutter effect [things] when it’s just the camera captured it at the right frame at the right angle at the right moment of that scan. And I’m going to find it.”

He never did. Pineiro estimated that he watched 700 to 1,000 hours of gameplay, between the videos he captured on the original equipment and those from other members of the community. Not once did he see a single instance of the three-girder pattern. “I’m like, wow, this is really damaging because the arcade does not perform three girders. It doesn’t. It doesn’t generate the graphic that way. It’s five,” he said.

The evidence package makes a point of stating that the major developments in the investigation and testing process originated from Mitchell’s team, not from the tests being conducted by Twin Galaxies. In particular, it points to the efforts to produce stable color from the Two-Bit Converter. Pineiro agreed that he and those helping him made breakthroughs Twin Galaxies could not, including on the color issue. What he left out of his official reports, however, was that maintaining this color wasn’t just a matter of finding the right VCR and replacing the dried-out capacitors and resistors on the Two-Bit Converter. To record color, someone also had to place a finger in a certain position on the convertor’s chip and hold it there the entire time, Pineiro told me. He speculated this was because poking the chip in the right place increased the resistance by just enough that the VCR could interpret the signal.

Pineiro told me there were theories that he never tested, like a faulty power supply unit, but that’s because a bad PSU would likely shut down or permanently damage the game board before anyone could complete a record on it. Authentic Donkey Kong boards are rare now, and no one wanted to risk one for the tests, which Pineiro thinks says something about the plausibility of the idea.

Both Kleisath and Pineiro told me that Mitchell never once asked them to lie. Pineiro even had what he described to me as a come-to-Jesus moment with Mitchell, when the two were alone in the shop one night. “I said, ‘Billy, is there something you want to tell me? Look, the best I can do is, if you want me to help you with this, I’ll just pull out. I’m a nobody,’” Pineiro said. “And he literally looks at me straight in the face and he goes, ‘No. I want you to say the truth. I want you to say what you see.’”

So that’s what he did. Pineiro prepared a report and sent it to Kleisath, who cleaned up some typos and posted a faithful version to the Twin Galaxies dispute thread on the night of April 9th, 2018. “My Conclusion on the 1.047 & 1.050 game tapes is that they were NOT generated from a Genuine Nintendo Donkey Kong PCB.… Repeated testing and viewing of the game on those tapes do not demonstrate the signatures found on recordings coming out of Genuine Nintendo Donkey Kong Arcade boards,” the report concludes. The decision against Mitchell came down three days later.

Immediately, Kleisath said, Mitchell and Childs stopped speaking with him. “As soon as that verdict came down, virtually never heard from them again in any way shape or form. We’re talking about a seven-year, eight-year friendship, and all I did was relay a technical conclusion, a final report from Carlos Pineiro that they already knew. It’s not like they’re getting blindsided.”

Kleisath described repeated efforts to reestablish some sort of friendship with Mitchell and Childs, but he was never able to break through, and the relationship eventually soured beyond repair. When he sent Billy Mitchell Jr. a Facebook message asking if he could attend the next Retro Arcade Night, now being held without his involvement, the response called Kleisath’s presence “a cancer that needs to be repressed” and said he would be “escorted out by a police officer” if he attended.

Among other claims, Billy Jr.’s message referred to a conversation Kleisath had with a member of the community named Eric Tessler about the disputed scores. Kleisath doesn’t deny that he might have expressed skepticism in private, but he doesn’t think the response has been justified. “I even called Eric and asked him and he goes, ‘I don’t remember you saying anything that would cause them to be as pissed off as they are,’” Kleisath told me. Tessler did not respond to my request for an interview.

Carlos Pineiro, however, stayed on good terms with Mitchell even after the verdict, despite the fact that his conclusions played a pivotal role in the ruling. A signed statement from Pineiro appears on the third page of the evidence package, just after the table of contents. It’s one of many similar statements in the package, each of which includes a note that the signatory believes what’s written on the page is true “under penalty of perjury.” This addition makes the document a sworn declaration, essentially an affidavit signed without the presence of a notary.

The third item in Pineiro’s declaration reads, in part, “After seeing the evidence, I retract my conclusions from the dispute case. Billy Mitchell did not cheat.”

As he explained both over the phone to me and in a lengthy YouTube video, Pineiro did sign this statement, but only with the understanding that the document would never be made public, and that Mitchell would remove the retraction of his conclusions—which Pineiro told me he still stands by—and the mention of cheating. When he learned that the statement had been sent to Twin Galaxies unmodified, he was outraged. He contacted a lawyer, arranged a meeting with Mitchell, and negotiated a new version of the document that he was more comfortable signing.

Initially, Pineiro had only agreed to speak with me off the record, for fear of tarnishing his relationship with Mitchell. The morning the statement he’d signed was made public, he elected to move all of our previous conversations on the record.

Throughout this dispute process and in the months following, David Race, the current world record holder for the fastest perfect Pac-Man game, conducted his own tests and analysis. I spoke with Race over email in May about his findings, which he had declined to submit to Twin Galaxies because he felt the dispute process was a “sham” and a “long exercise in poisoning the well in order to come to only one conclusion.” At the time, he told me his tests were inconclusive, that he was unable to determine decisively whether the games were or were not played on arcade hardware. He also raised the notion that Dwayne Richard could have modified the tapes by splicing MAME signatures into a genuine arcade recording. A portion of our conversation appears in the evidence package. Amusingly, the document says I write for “Electronic Gamers Magazine.”

Shortly after Mitchell submitted that package to Twin Galaxies, however, Race issued a public statement explaining that he had previously been unaware of the 2006 MTV interview with Robert Mruczek that challenges the idea Dwayne Richard could have modified the tapes. “Based on this information I would like to offer my apologies to Dwayne with respect to the idea he may have been responsible for perpetrating a hoax by altering frames of the 1,047,200 and 1,050,200 games. Dwayne, I’m sorry,” Race writes.

Through an intermediary, Race declined to speak with me again to clarify his current perspective, but the rest of his September statement offers insights into his thinking. He questions Robert Childs’ declaration from the evidence package, in which Childs says his technicians designed the direct feed setup with “technical expertise [he] did not possess” and that he retained “little to no information” about the setup. Race claims this is in direct contradiction to information he received from Childs, specifically noting the detailed Facebook post that first caught Carlos Pineiro’s attention.

“I don’t like being lied to. I don’t like having my time wasted, and I certainly don’t like it when someone tries to gaslight me or others,” Race’s statement reads. “Rob Childs was more than certain about his analysis, and now we are supposed to believe that he never really said or explained the setup, that it was all a figment of our imagination. Rob can’t remember all that was involved in the recording of the 1,062,800 game? Both Carlos and I just started testing Two-Bit Converters on a whim? We’re testing Gigaware capture devices into laptops because we just felt like it? Sorry, that nonsense doesn’t fly with me.”

Race also says he, like Pineiro, was presented with a prewritten sworn declaration. “I was asked to look over and sign a couple statements but declined.”

In spite of all that, Race does not conclude in this statement that Mitchell cheated, and instead calls for further investigation. “Billy Mitchell has been accused of many things. The onus of proof still lies with his accusers,” he writes.

After these recent developments, Mitchell no longer appears to have an expert who’s wholly in his camp and willing to argue publicly against the technical evidence in his case, at least for the time being. But as he has frequently stated, he considers the statements of eyewitnesses just as important to his defense as any videotape.

“I had somebody tell me once, there’s people who believe Neil Armstrong never went on the moon. It was just a hoax. And so they did a study, what if it really, really was a hoax? There were over 400,000 people that lied,” Mitchell told me in Banning, during our final interview of the day.

Mitchell has not quite produced 400,000 witnesses for his scores. The evidence package, as submitted to Twin Galaxies on September 9th, contains sworn declarations from six people who say they saw Mitchell break a Donkey Kong record during at least one of his three attempts and an additional two individuals who say they were involved but do not specifically state they witnessed the high scores firsthand.

The possible explanations for these statements are few. Any skeptic would need to argue that these people: one, were mistaken in their recollections; two, signed their names to statements they knew to be wholly or partially false; or three, were fooled at the time of the original events by a ruse that made them believe they were witnessing a record when they were not.

In the course of my own reporting on this story, I heard eyewitness accounts that differed from the testimony in the evidence package, from the sources’ own previously documented statements, or from the testimony of other individuals. These differences are not always dramatic, but they are worth noting nevertheless.

Robert Childs’ statement, signed in July, states outright that the King of Kong tape was recorded in his warehouse. In May, when I asked Childs directly about the tape and whether it was recorded at his business, he told me, “I really cannot remember. I mean, it’s possible that he did it in my warehouse. I cannot remember.”

A statement from Josh Houslander, a member of the Twin Galaxies staff during Big Bang 2010, says that the Twin Galaxies referees and personnel “all seemed very comfortable” with the decision to accept the Boomers scores and that “no one expressed any reservations.”

David Nelson, who was chief referee at the time and told me he has no stance on whether or not Mitchell cheated, does remember controversy surrounding whether or not to accept the scores. He told me the referees discussed the issue for hours, and were particularly hung up on the fact that Mitchell had not allowed Twin Galaxies to arrange for an impartial referee.

“When someone is going to set a world record of this caliber, really the procedure should be to contact Twin Galaxies, tell them of your intention, and we will work out how to get a referee to you to witness it, and the referee will be one of our choosing. Billy went ahead and selected his own referee to witness his score, and he did it in secret without anybody’s knowledge,” Nelson said. “It was a very difficult decision because none of us liked the circumstances but the decision came down to, you know, we’ll accept the score.”

Nelson also described a tense conversation with Mitchell and Steve Sanders, Mitchell’s friend since their showdown at the Life magazine shoot, in which the two encouraged Nelson to accept the score with an ultimatum. “I didn’t like how I was being addressed and being told, ‘Yes, if you don’t accept this score, there’s going to be trouble.’ It’s hard to take that not as a threat, but I took it more as, well, he had plans. He had plans to make the score a big deal, and he had plans to announce it here, and if Twin Galaxies says they’re not going to take it, oh, that’s going to screw up all of his plans. But then I got from Steve Sanders, I got him telling me, ‘Hey, Dave, do the right thing.’ That didn’t sit well with me either. Anybody who comes to you and says, ‘Do the right thing,’ they don’t mean do the right thing. They mean do the right thing for them. Do what’s in it for them.”

Patrick Scott Patterson, then the assistant chief referee, told me he heard a similar version of events from Nelson immediately after the confrontation took place. He also echoed the idea that at least some of the referees had reservations about accepting the scores, him included.

Though no signed statement from Todd Rogers regarding the Boomers score appears in the evidence package, during our interview Rogers told me with absolute certainty that he handed the tapes of both the Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. scores, which have since disappeared, to Nelson. Nelson told me he never had possession of the tapes, despite asking Rogers for them multiple times. “If anybody were going to receive them, it probably should have been me or one of the other arcade referees, but no, I never saw them,” Nelson said.

Rogers’ statements on how he became involved in the events at Boomers have also evolved over time. In a video recorded at Big Bang, he says, “There was no intent at the beginning to make any records. I went down there to shop for tarantulas.” Rogers collects spiders, and his shop of choice, Strictly Reptiles, is in Hollywood, Florida—close to Boomers but across the state from his home. In the Big Bang video, he goes on to reiterate that “nothing was arranged” but says he eventually goaded Mitchell into attempting a record.

During our interview, Rogers told me that he drove down “primarily” to buy tarantulas. “I think Walter [Day] had mentioned something to me briefly beforehand,” he added. Day was no longer running Twin Galaxies by that point, so any communication would presumably have occurred in an unofficial context.

If the record attempt at Boomers was spur of the moment for Rogers, it was not for Mitchell and Robert Childs. Multiple statements in the evidence package speak to advance planning with the arcade and the man who lent a Donkey Kong cabinet for the attempt. Furthermore, during my conversation with Childs, I helped him uncover old text messages to one of his friends, Brett Circe, from the week in question. He read them aloud to me on the call.

“‘Billy to take the DK and DK Jr. record back on Saturday at Grand Prix,’” Childs said, reading a text to Circe in advance of the event. “‘Cool, I am out of town this weekend. Keep me informed,’” came the reply.

Then, on the day of, at 7:24 p.m. ET, Childs followed up: “‘Billy took back both records today.’ Brett texted me back, ‘Woot.’” In the video Childs allegedly recorded after the Donkey Kong Jr. score, he says Mitchell had to pull him out of bed to come film this celebratory clip. When we spoke, before he read the texts, Childs said he did not remember the timeline of that day but thought the attempts went on until at least 10 o’clock at night. In Banning, when I questioned Mitchell directly on the timeline, he explained the discrepancy by saying they stayed at the arcade to eat, celebrate, and clean up until around 11.

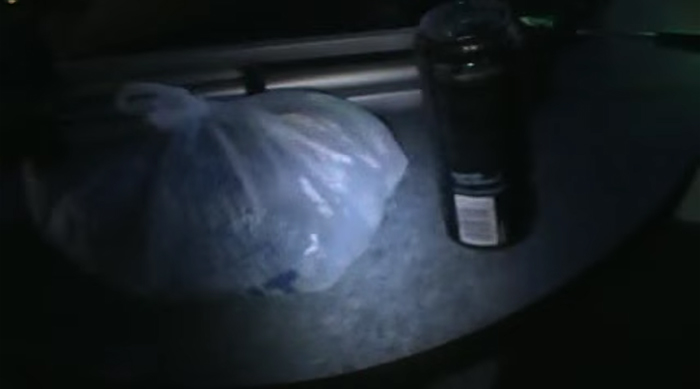

That video raises a far stranger point of contention, as well. Around 30 seconds in, Mitchell says Rogers has the tapes of the performance, and Childs zooms in on a white grocery bag nestled between a tripod and a can of Monster Energy drink, saying the tapes are inside. Rogers flexes his biceps to prove he’s capable of protecting such precious cargo.

Carlos Pineiro recounted a conversation with Rogers—months after Twin Galaxies had issued its verdict against Mitchell—in which Rogers told him the bag did not contain any tapes. According to Pineiro, Rogers said the bag instead contained two tarantulas he’d purchased earlier in the day and loose newspaper added to make it appear full.

Rogers told me he did not remember whether the tapes were in the bag. More broadly, when I asked Mitchell, Childs, and Rogers whether the other two videos were staged or falsified like the board swap video, they told me they could not recall or did not directly address the question. The evidence package, it’s worth noting, only treats the board swap as falsified in any way.

But the muddiest aspect of the Boomers story, by far, is whether Pete Bouvier, Twin Galaxies’ owner at the time, was present. In the video Robert Childs allegedly shot “moments after” the Donkey Kong record, Mitchell says, “One more person we’re hoping to say hi to is Pete. Pete from Twin Galaxies is on his way here.” In video footage from the announcement at Big Bang 2010—captured on Saturday, August 7th, exactly one week after the events at Boomers—Mitchell makes statements that, by any reasonable interpretation, indicate Bouvier was not present. Describing the events immediately after he set the Donkey Kong score at Boomers, Mitchell says:

“Pete was on the phone. And Pete was on his way over, so I thought, this will be great. I’ll introduce him to the manager.… So, Pete was on his way there and I turned and I said to the two Twin Galaxies people there [Rogers and his then-girlfriend, Kimberly Mahoney], I said, one more thing I gotta take care of. And I started a game of Donkey Kong Jr. And I think it was neat because I think it would have been the first time Pete had seen a world record. Am I right? [Mitchell looks offscreen, apparently to Pete] No. [Mitchell laughs] So I played, and I guess I was around three-quarters of the way through before I said, ‘Wait, where’s Pete?’ And then Todd said, ‘Oh, he’s not going to be able to make it.’ So that’s the story about Pete.”

The first recorded instance I have been able to discover of Billy Mitchell claiming Bouvier was physically present at Boomers during the two score attempts did not occur until after Bouvier passed away in September of 2017. During a panel at the 2018 Southern-Fried Gaming Expo, he said Bouvier congratulated him and shook his hand immediately after he broke the record, going so far as to impersonate the deceased man’s voice.

Mitchell told me in Banning that Bouvier was present for the Donkey Kong record but had left before he played Donkey Kong Jr. “He was there. He was happy. He was congratulating me, all that stuff. Are you saying that he walked up and the game ended five minutes earlier? Now, let’s say you’re saying that. I’m not going to swear to that either way, but he was there when we went and sat down and ate—because the arcade has the snack bar—he sat with us,” he said.

I pulled up the Childs videos and the Big Bang announcement on my phone and we watched them together, but Mitchell didn’t address the specific phrasing he had used in 2010, instead stating again that Bouvier had been there but left, that he’d gotten confirmation of this from someone in Bouvier’s family, and that Twin Galaxies personnel had attested that Bouvier was very comfortable with the scores.

Todd Rogers told me during our interview he was certain Bouvier was there. “One hundred percent?” I asked. “Absolutely,” Rogers replied.

In his sworn declaration, Childs states definitively that Bouvier was present for the Boomers score. When I spoke with him on the phone in May, his words were more tentative. “Yeah, there was an older gentleman, and I was not introduced to him because there was a lot of different people there. But I do remember an older gentleman there, and I was told that he was like one of the main guys at Twin Galaxies,” Childs said. “I mean, I did not talk to him or anything like that.”

The attendees of Big Bang 2010 with whom I spoke disagreed on Pete Bouvier’s attitude toward Mitchell and how strongly he pushed back against accepting the scores, if he did so at all. But none of them, apart from Mitchell and Rogers, believed Bouvier had witnessed the records firsthand.

“I certainly can’t confirm or deny whether or not Pete was there or not, but I can say it would surprise me if he was,” said David Nelson. “That wasn’t anything Pete really did.”

Here’s Michael Sroka, who told me he filmed footage of the announcement and an interview with Mitchell at Bouvier’s request: “I mean the way he asked me to do it and the mannerisms of how it came all together so quickly, you know, I believe Pete didn’t know about it until Saturday. You know, just the way he interacted with me about, ‘You need to film this. You need to do this.’ It seemed like he had no clue about it.”

And Patrick Scott Patterson on the discussion surrounding the scores: “At no point during any of this did Pete Bouvier ever indicate that he was there. At no point during any of this did Pete Bouvier indicate that he believed Billy Mitchell’s claims, [or] that he had witnessed Billy doing anything. He didn’t even want Billy to do the things that he was doing. The way that it was always told to me, that whole time by Mitchell, was that Todd Rogers witnessed it. And the thing that was worth the most note about that on both ends is that even if Pete had been there, he was not a referee.”

One added wrinkle to this question comes from Mitchell’s statements that Bouvier brought an unspecified family member (or members) with him to Boomers. When I asked Rogers who that might have been, he told me it was Nancy, Pete Bouvier’s wife of 33 years. “She was usually with him everywhere he went.”

Mitchell, though, said it wouldn’t have been Nancy, because she didn’t really involve herself in anything related to gaming.

Before either of these conversations, I had already made contact with Nancy Bouvier. Mitchell knew I had spoken to her. Rogers didn’t.

When I asked Nancy whether she or Pete had been present for the record attempt, she said she did not recall the events in question. I thanked her for her time and provided a bit more context as to why I was reaching out. One of the three sentences in her brief response was “I do not have fond memories of Billy Mitchell.”

Despite his reputation as a villain, Mitchell struck me in our interactions as surprisingly tame, at least in his personal life. During our final interview in Banning, I asked him if he had any vices. He was never a drinker or smoker, he said, nor did he like to spend money on ostentatious things. The best answers he could come up with were popcorn—and feet.

“Just mine. Just mine,” Evelyn chimed in.

“I rub her feet,” Mitchell added as clarification. Rarely has the line between “sweet” and “too much information” been so thin.

One of the phrases Mitchell pulled out over and over again during our conversations was that “playing games is the least important thing” he does. He considers fan interactions and the work he does to promote classic arcade gaming far more significant than any score he might obtain. He also donates the proceeds of Rickey’s second-highest-volume hot sauce to charity, he said.

Those close to Mitchell described the gestures he’s performed, large and small, to demonstrate he cares. Richie Knucklez said Mitchell sent his daughter, Faith, a huge, embroidered Toy Story rug after learning it was one of her favorite movies. Carlos Pineiro said Mitchell surprised him with a box of custom hot sauce featuring the logo of his wife’s catering company, so she could hand bottles out at events.

Billy Mitchell Jr. described his father as endlessly supportive of his dream to play football, recounting the time and money he poured into making it happen. Mitchell enrolled his son in the school with the best football program in the area and drove him back and forth each day, despite the fact that it was nearly 50 miles from their house.

“My dad never did anything for himself,” Billy Jr. told me.

In fact, many—though certainly not all—of the people I spoke with on both sides agreed that Mitchell isn’t the smug, arrogant bad guy he seems from afar—even if he can still be a little smug and arrogant at times, especially when it comes to gaming.

“In general I will say Billy Mitchell comes off as somewhat a pompous ass. But once you get to know him, it’s all an act and is done in jest. He has a kind heart and it really is all done to promote his persona and promote classic gaming,” Greg Erway said.

“He doesn’t look down on anyone and he tries to uplift everybody,” TriForce Johnson said.

“Honestly, if you’ve never met him and you were to meet him in person, super swell guy,” Carlos Pineiro told me. “Super nice. He’s not that evil guy that he plays in that documentary. He really is funny. He’s super enjoyable.”

“He’s not staunch, he’s not a prick, he’s not an asshole like some would think,” Todd Rogers said.

“He’s done a lot for the classic scene. Whether people like him or hate him, or want to admit it or not, he’s kept classic gaming relevant for a lot of time when it wouldn’t have been without him,” Tim McVey told me. “He’s been good for gaming. And I think, in general, he’s a good guy. I don’t have anything ill to say about him as a person. He’s been great to me.”

McVey, however, preceded those statements with a few words about the dispute. “I wish I knew the truth to this situation. I wish I knew, did he really cheat? And if he did, fuck, man, own up to it. You embellished a score, admit it, move on. People would have forgiven you and gotten over it by now already.”

I asked TriForce Johnson how he’d react if Mitchell came to him and confessed that he’d cheated. “My advice would be, you already fell into the pit,” Johnson said. “Just admit to everyone, ‘Listen, look, you know, this is not worth my family,’ et cetera. You come out with an official speech. You take the burn. You take the burn. The burn will go away and you’ll heal over time.… It doesn’t make sense to continue to fight it.”

But Johnson also told me he wouldn’t want it to come to that, that he wouldn’t want Mitchell to confess to him in the first place even if he’d done something wrong. Johnson compared the hypothetical to an anime series, Code Geass, in which one character’s lies give his allies the strength to fight for something bigger. “One of them found out that he lied, and you know what the girl said? ‘Lie to me again.’”

Even Dwayne Richard, a man who’s spent years railing against Mitchell, said he’s willing to bury the hatchet. “I’ve already forgiven Bill,” he said. “But there’s a difference between forgiveness, and reconciliation. I can forgive Bill, but he doesn’t want to be reconciled.”

In the process of reporting this piece, Billy Mitchell repeatedly attempted to direct my attention toward the finances of Jace Hall, Twin Galaxies’ current owner. Hall was involved with an esports venture called the H1Z1 Pro League, which collapsed in dramatic fashion in late 2018, with many of the parties involved reportedly going unpaid in the immediate aftermath. Reporting on the events does not paint Hall in a positive light, but it’s difficult to see any immediate connection to Twin Galaxies and the dispute.

Whenever Mitchell brought up the topic, he did so through a series of questions rather than specific allegations, often pointing out that his dispute thread was the longest and most heavily trafficked in Twin Galaxies history: If you were in dire financial straits and had a chance to increase hits on your website, wouldn’t you take it? This implication faces a few obvious difficulties, namely that Jeremy Young, not Jace Hall, was the one who initiated the dispute thread, and that he did so weeks before the H1Z1 Pro League was announced to the public. No one I spoke with indicated that Hall played any significant role in the dispute until the community had already produced the technical evidence at the heart of the case. In the absence of any specific motive, it’s Mitchell’s other rhetorical questions, about Jace Hall’s character, about the “kind of man” he is, that appear to be the point.