Wander the corridors of Control’s Oldest House long enough and you’ll be hit with an eerie sense of familiarity. Despite the contemporary setting, Remedy’s action-thriller feels thoroughly historical. Everything from the architecture to the office furnishings point to a bygone era. The building’s occupant, the Federal Bureau of Control, isn’t some cutting-edge government agency, but a relic of the post-war era, stuffy and old fashioned. The Bureau’s headquarters also appears stuck in the past, its meandering hallways and concrete atriums eliciting the same nervous energy as existed during the height of the Cold War.

In the 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, visitors from another world set about consuming the minds and bodies of a small American town. What begins as an external threat ends up as an internal malevolence, with colleagues, friends and family turned against each other. The aliens’ purpose is clear: infiltration, control, and, ultimately, annihilation.

American cinema in the ’50s saw a fresh wave of sci-fi films—The Thing from Another World, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Invaders From Mars—all of which explored concerns around an infectious outside enemy that slowly turned Us into Them. While the films were rarely explicit in their messaging, it’s now widely acknowledged that this “Them” stood in some form for communism and the Soviet Union’s growing power and influence. These post-war films grew out of an environment of panic and hysteria over the idea of communist intrusion and subversion. At the same time, American Senator Joseph McCarthy was spearheading an intense culture of suspicion and paranoia now referred to as the “Second Red Scare.”

Credit: 505 Games

Elsewhere, in a rural Wisconsin town called Ordinary, an alien force breaches our world through an other-dimensional slide projector. A strange, swirling red entity known as the Hiss begins its invasion, quickly taking control of the Bureau and its HQ. This is the set-up to Control—a modern Cold War sci-fi thriller that evokes many of the same Atomic Age anxieties and apprehensions seen in earlier period films.

Of course the color of the Hiss is the most explicit giveaway. Its presence corrupts areas of the Bureau building, bathing them in an ominous red glow. The form of the Hiss also follows closely to the father of communism’s own description in his Manifesto: a haunting specter. Control’s Hiss spreads and contaminates just as the American government of the Cold War era feared communism would. Beyond the symbolic red, the Hiss also controls. As the entity expands its influence throughout the building, Bureau employees are turned, like American citizens subjugated by alien Body Snatchers.

Credit: Beyond My Ken

(CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Bureau building, the Oldest House, is itself a monument to the Cold War, modeled on the John Warnecke skyscraper that sits at 33 Thomas Street in Manhattan. This gray slab of concrete was built to withstand an atomic bomb, and like so many other Brutalist structures, was constructed at a time when the West was still recovering from the trauma of two World Wars, while simultaneously bracing for a new, nuclear conflict with the Soviets.

In the world of Control, nukes have been swapped out for Objects of Power. These are iconic everyday items—a handgun, rotary-dial telephone, ashtray, analogue television, and even—as if the parallel wasn’t explicit enough—a Soviet-era diskette containing nuclear launch codes. Each object is possessed by some other-dimensional force, is immensely powerful, and can be used as a weapon, granting powers like telekinesis and mind control.

These Objects of Power are locked away deep within the Oldest House. An immense government complex shrouded in mystery, the House is also home to several gateways—known as Thresholds—to other dimensions, where powerful entities threaten to leak, like faulty uranium reactors, into our own world. In order to protect against the transmission of these forces, the Bureau utilizes a fictional material called Black Rock.

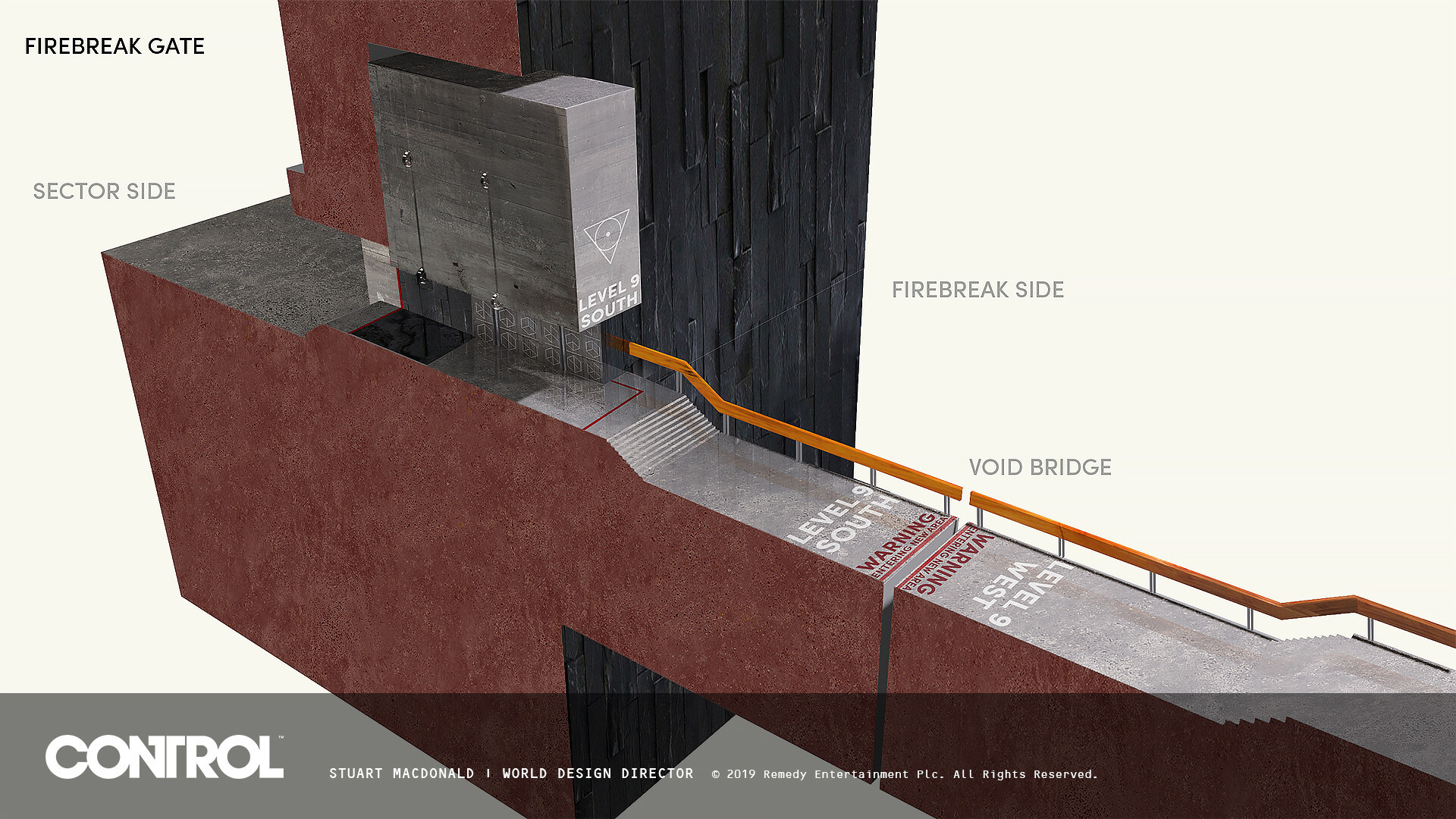

Massive firebreak doors made of Black Rock partition different areas of the building, while sets of “hypercubicles” in the Communications Department ensure Bureau equipment is guarded from the strange resonating effects of the building. Remedy’s director of world design, Stuart Macdonald, has said that Black Rock was inspired by magnetite, a real mineral that was added to concrete mixtures in order to increase radiation shielding during the Cold War.

Credit: Working Title Films / Studio Canal

So much of Control’s visual design is inspired by classic Cold War thrillers. One influence is Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, particularly Tomas Alfredson’s 2011 adaptation and its memorable depiction of the British Intelligence’s HQ in 1973, codenamed “The Circus.” The Head of MI6, played by Gary Oldman, is even called “Control” (though that one, admittedly, might just be coincidence). The offices of the Oldest House are reminiscent of The Circus’ secretarial pool, with its intense overhead strip lights, ordered grids of desks and endless rows of boxy filing cabinets. Control’s various soundproof rooms are also visibly similar to The Circus’ smoky meeting room, where padded walls insulate from prying ears as well as eyes.

Credit: Hawk Films / Columbia Pictures

Another inspiration can be found in the work of production designer Ken Adam. Like the more modern Tinker Tailor, Stanley Kubrick’s classic Dr. Strangelove beautifully recreates the paranoid tensions of the Cold War era. One of the most pronounced elements is its use of analog equipment that today seems clunky, with government facilities crammed with computer consoles, rows of buttons, and whirring tape decks. This is another element Remedy leans into for the design of the Oldest House. In fact, upon entering the building you’re confronted with a short memo explaining that digital tech is prone to malfunctioning, and so the Bureau must make extensive use of antiquated equipment—typewriters, film projectors, punch-card computers, even an entire pneumatic-tube mail system.

Credit: Hawk Films / Columbia Pictures

Of course, Kubrick and his production designer Ken Adam are just as well known for their spectacular sets as they are their props. Steven Spielberg once described the “War Room” from Dr. Strangelove as “the best set ever designed.” Like so many of Control’s own memorable areas—the atrium of Central Research, the Ritual Division, the Synchronicity and Parapsychology labs—the large, open interior sets of Ken Adam were designed to be conceptually unique as well as to impress with scale. Adam’s War Room is a central influence, its wall-sized world-map criss-crossed with blinking trajectories and flashing targets recreated in the Oldest House’s own Logistics area. The War Room’s polished black floors are also key, reflecting the room’s illuminated maps. These floors are continually mimicked by Control in the form of the game’s much-touted “RTX technology,” which ensures the continuous presence of glaring console screens, as well as the pervasive red mood lighting of the Hiss.

Credit: 505 Games

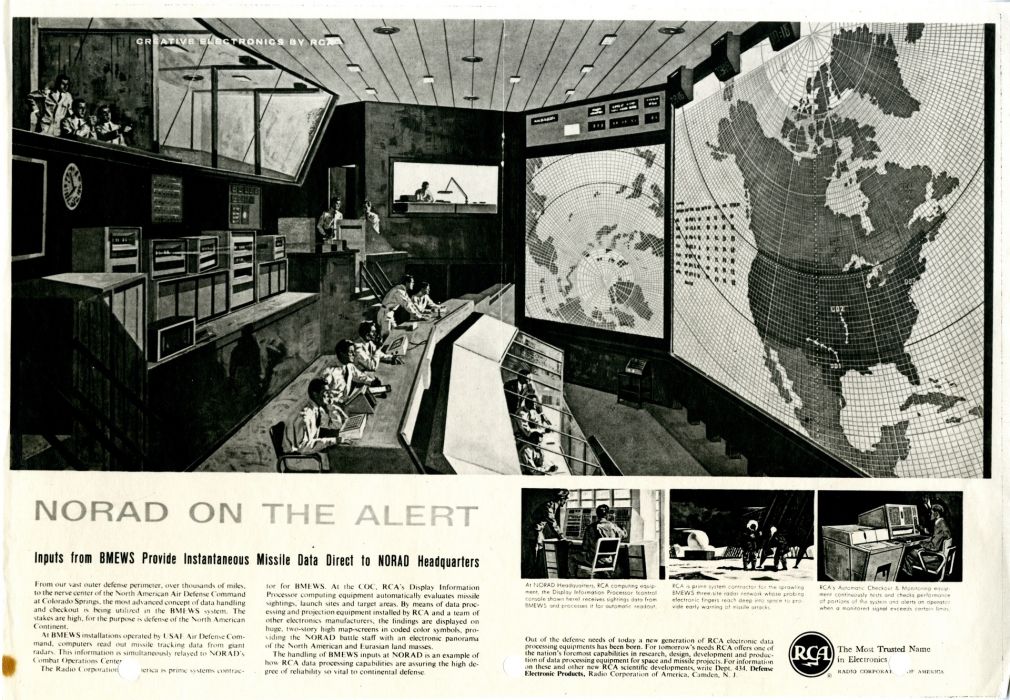

In Strangelove, the map is a physical representation of the intense stand-off between America and the Soviet Union, suggesting the varied possibilities of communist attack as well as nuclear annihilation. In Control, it depicts the appearance of Altered Events and Objects, and the growing threat to humanity that these other-dimensional entities present. These control room maps have become one of the most recognizable icons of the Cold War era. Adam was himself influenced by the existing North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD), a specialist government organisation that would provide early warning in case of nuclear attack.

While Dr. Strangelove’s War Room is probably Adam’s most famous set, the British production designer and ex-architect is just as well known for his work on the James Bond franchise. Adam was involved with the films from the get-go, starting with 1962’s Doctor No and working on the series until 1979’s Moonraker. Like the War Room, many of his futuristic Cold War sets from the 007 films have become a kind of visual blueprint for what many people remember about the conflicts of that era. The evil mastermind’s modernist mansion, the underground facility, even the moon base—Adam’s sets were as diverse as the imagined locations of any video game.

Credit: Eon Productions / United Artists

James Bond is remembered for its casual anti-Russian stance, but more potent is the general conspiratorial atmosphere. Secret organizations, clandestine government agencies and experimental weaponry all combine to create something that feels uniquely Cold War-esque. One of Adam’s most spectacular sets is the volcano rocket facility from You Only Live Twice. The base, like the earlier War Room, is faintly modernist, with then-contemporary furnishings, tons of scientists working on their gizmos, and even reflective marble floors. Constructed largely from concrete, at the back of the base sits another NORAD-style world map, where the villain presumably plots world domination.

The underground labs and reinforced concrete meeting rooms that James Bond is so often seen infiltrating continually appear in a similar fashion throughout Remedy’s Oldest House. Many of Control’s large-scale set-pieces and locations, like the Black Rock Quarry and Hedron Chamber, also feel reminiscent of Adam’s million-dollar sets, like the War Room and Volcano. While they may not be a complete one-to-one match, Control’s visual identity is consistently Cold War–esque, and production designers like Ken Adam were the ones to cement the aesthetic of that era’s long conflict, as well as the spy thriller stories which arose at the same time.

Control’s paranatural plot regarding a red entity from another dimension isn’t some kind of strict metaphor for communism. More accurately, its the general atmosphere of the game which evokes anxieties and fears around the spread of something malignant, that’s really important. Remedy, a Finnish developer, is continually shrewd in its handling of American popular culture and expert at taking moody snapshots of particular historical periods. In its previous game, Quantum Break, its sights were on American capitalism and 21st century corporate power. Instead of mid-century modernism, it was sleek postmodernism. In the same way, Control represents a general depiction of 1950s, 60s and 70s America, when government institutions like NASA and the FBI still had huge power and influence, and an irrational fear of Soviet influence prevailed over everything.

Header Image: Control, 505 Games

Ewan is a writer from London with an interest in science fiction, architecture and game environments. He has work published at Eurogamer, Rock Paper Shotgun, The Verge, The FACE, Wireframe Magazine, VICE and Gamasutra. If you’re into nice photos of big buildings then follow him on Twitter @ewanwilson4.