Much like Cloud’s memory, Final Fantasy VII‘s significance has gotten a bit muddy as time goes on. Debates about the actual game—whether it’s overrated or if it still holds up—have raged on for over two decades, but there’s much more to Final Fantasy VII‘s legacy than what was burned to three PlayStation discs back in 1997.

Final Fantasy may have been a successful niche series in America before it’s seventh entry arrived, but that didn’t necessarily indicate that RPGs were a lucrative genre. In Japan, console role-playing games rained money on developers. Enix’s Dragon Quest IV sold over 3 million copies in the country, and the series as a whole was so popular it led to an urban myth that Japanese laws were passed to forbid releases on school days. In the U.S. the games were known as Dragon Warrior, and the first in the series was given away free with Nintendo Power magazine subscriptions. After that brand-building promotional blitz, Dragon Warrior IV sold under 100,000 copies in the United States. As a result of those underwhelming numbers, Dragon Warrior IV was the last entry English speakers would see for over a decade. Dragon Quest V and VI, both of the 16-bit entries in the series, skipped the Super Nintendo entirely.

The SNES sold 23.35 million units in North America, but only a fraction of those would ever have RPGs inserted into their cartridge slots. Both Final Fantasy IV (initially Final Fantasy II in the U.S.) and Final Fantasy VI (initially Final Fantasy III) sold just over a million copies in North America—combined, not each. And those numbers were a ceiling, not a floor, for a company interested in bringing an RPG to America. Final Fantasy publisher Square’s other offerings yielded even lower returns. As far as JRPGs were concerned, Square had built a small but dedicated audience in the West, and releasing them in America remained a risky proposition.

One of the biggest problems was basic awareness. The most popular games in the U.S. at the time were platformers and action-adventure games. Going from jumping on turtles’ heads as Mario or jump-shooting as Mega Man to navigating menus and balancing equipment buffs wasn’t an easy transition. Compared to the relatively comprehensible mechanics of action games, RPGs required a steep learning curve in an era lacking cohesive tutorials. Once you got past the barrier of entry, you might find the great story underneath, but depending on what you played, that wasn’t exactly a guarantee.

There were, however, some meager attempts to engender familiarity with the genre. Nintendo Power gave a few pages per monthly issue in an “Epic Center” column focusing on adventure games and RPGs, but the accompanying FAQs barely helped you through a select few areas in a single game. Given the minimal amount of releases, several installments of the column concerned games from Japan with no North American release confirmed.

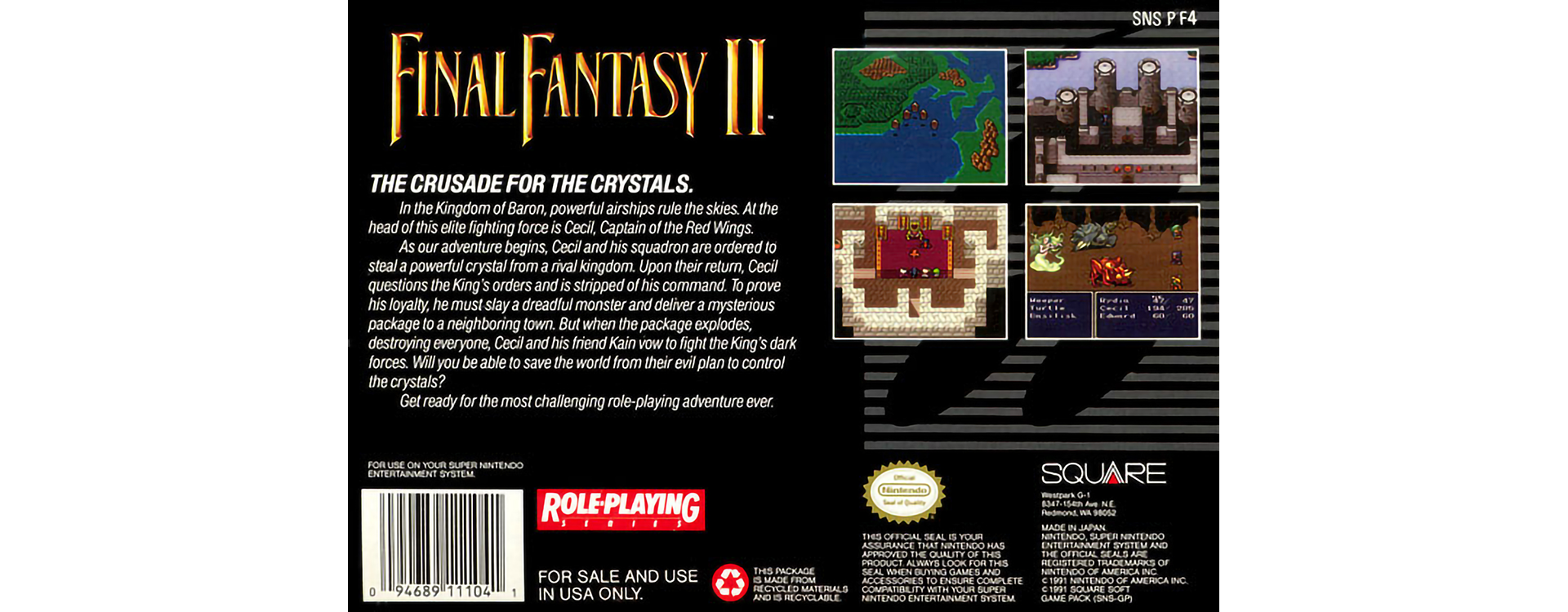

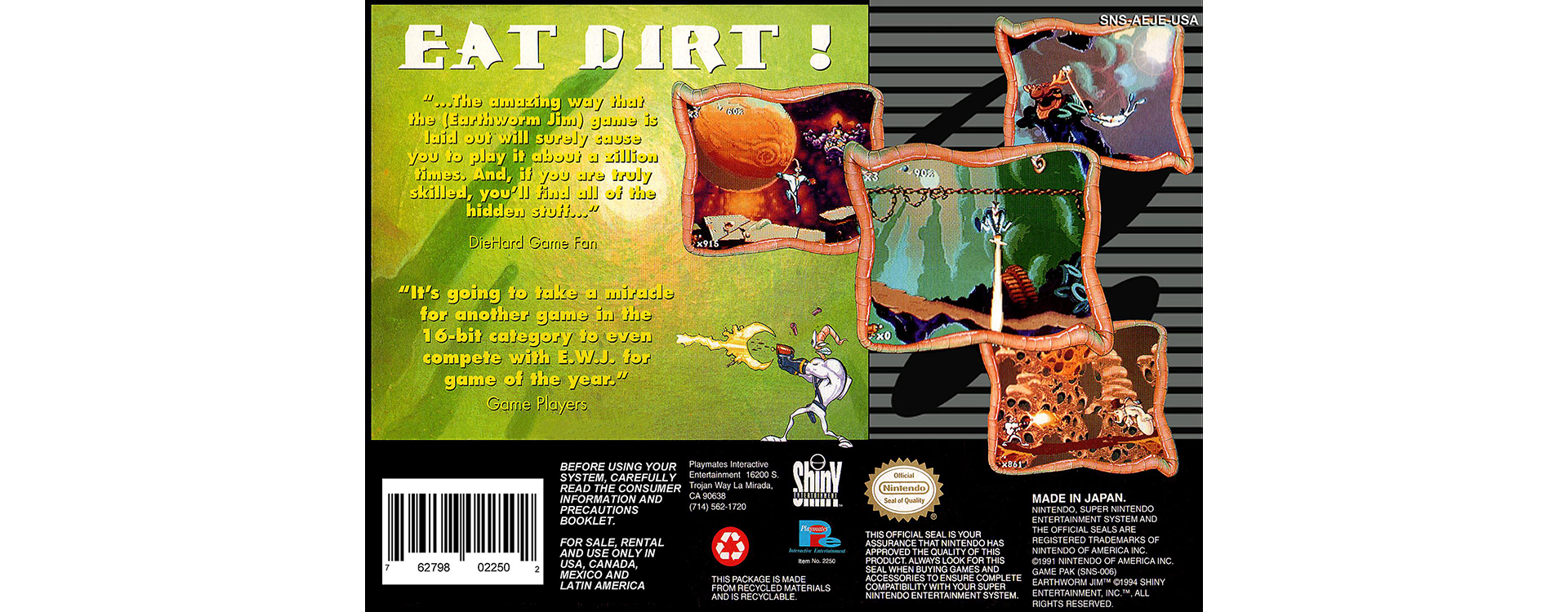

Another reason why RPGs weren’t as attention-grabbing in North America was how game boxes generally presented RPGs. Images of action menus and screenshots of two small character sprites talking weren’t nearly as appealing as something like the box for Contra, where commandos are blowing up alien bosses that took up half the screen. While publishers knew that the stories were what set RPGs apart, paragraphs of text on the back of the box weren’t nearly as eye-catching as colorful images of motion and combat.

Here’s the back of Final Fantasy II’s box art:

Credit: Square

Now here’s the back of the successful action-platformer Earthworm Jim:

Credit: Playmates, Shiny Entertainment

Which one looks more interesting?

That wasn’t the extent of the marketing problems. Advertising in general was limited. Beyond some triple-A publishers, after school or prime time television rarely aired RPG spots. Comic books or gaming magazines were where a majority of the budget went. The rare times an RPG saw the semblance of an ad campaign, like Earthbound, the messaging missed the mark. A Square ad for The Secret of Mana aired late at night and didn’t display any graphics from the actual game, while communicating little of what the RPG was actually about.

The fact that the localization of any RPG was already a frugal project certainly didn’t help advertising budgets, either. Text-heavy adventure titles like Zelda aside, most games coming to North America could be localized as a one-man job. Intros, outros, menu screens, and manuals made up the majority of video game text in the ’90s. When you’re operating from a mindset that localization can be a solo effort, the reams of text in any RPGs mean translating all that content for a new audience will either require a substantial investment or cutting significant corners. Why put so much effort and money into bringing a game over if it wasn’t in a genre proven to sell?

Enter Avalanche

Final Fantasy VII began life as a Nintendo 64 exclusive, but Square later switched over to Sony’s PlayStation for storage reasons. The publisher, benefitting from its success in Japan and, to a lesser, extent, America, invested significant capital into the project. For its era, Final Fantasy VII was one of the most expensive video games ever produced up, with production costs of $45 million. The budget wasn’t just high by video-game standards, either. Square was crossing into figures comparable to the movie industry’s epic failure Waterworld. And even development wasn’t the whole story. The marketing budget for the game was rumored at $100 million—though Tomoyuki Tekechi, then-president and CEO of Square has more recently claimed the actual number was closer to $40 million.

No matter which number you believe, the figures are staggering for an RPG in that era. At the top end, $145 million, Final Fantasy VII’s total cost would’ve been almost three-quarters of the production budget for Titanic, which released the same year and was at the time the most expensive film ever made. Of course, it also became the first film to gross more than $1 billion in the U.S.

Those cinematic parallels are apt in more ways than one. When you’re playing with numbers that big, your only real options are to become Waterworld or Titanic.

Credit: Square

Square used the money wisely. First, it simplified and streamlined Final Fantasy, with fewer characters on the battlefield (three, rather than the series’ traditional four), less equipment to upgrade (weapon, armor, accessories, and materia—that’s it), less punishment from enemies, and fewer overall numbers to keep track of. Atmospherically, it dropped the the European fantasy worlds that had become closely associated with every JRPG not named Earthbound or Phantasy Star—a particularly bold decision for a game called Final Fantasy. Gone were black mages, paladins, and evil empires. In their place came a gritty metropolis controlled by a greedy, monopolistic corporation and a character with a Gatling gun where his hand should be.

To make matters more bizarre, while the European, Tolkienesque fantasy world was gone, plenty of fantastical, quasi-medieval weaponry remained. The main character was a mercenary carrying a sword bigger than his body. Another character was a pilot with a failed dream of going to outer space, but who also wielded a spear in battle. No big deal.

More logical, at least in theory, was the shift from sprite-based graphics to 3D models, reflecting the newest trend. But while the models used in actual gameplay were okay on their own, the real visual upgrades came from that popular PlayStation fad: full-motion video. FMV sequences had already been employed to bring crucial story sequences to life, but for Final Fantasy VII, they were more than just a storytelling device. FMV was a salesperson, allowing a chance to depict not just gameplay but the most visually ambitious versions of the characters and world in a way that players would actually see in the final game. Combine that with the insane marketing budget, and you might have a way to sell the masses on an RPG.

Rather than use all those dollars on selling to the profitable Japanese markets, Square spent just $10 million on marketing in its home country. The rest the publisher dumped into America and Europe, pounding consumers in prime time. Spots aired during The Simpsons, Saturday Night Live, and other highly rated shows of the day. Sony took on publishing duties in the West, making Final Fantasy VII the focal point of the PlayStation for 1997—an even riskier move.

The advertising displayed little of menus or turn-based gameplay. In fact, the commercials that have been preserved don’t show any gameplay at all. Instead, they show FMV cutscenes while hyping “a love that can never be” alongside a shot of Cloud and Aerith, and “a hatred that always was” accompanied by the iconic image of Sephiroth in front of flames. Depending on your reading of the story, these blurbs are either grossly incomplete or outright misleading. If there was a TV spot that showed the actual battles or in-game models, I haven’t been able to find it.

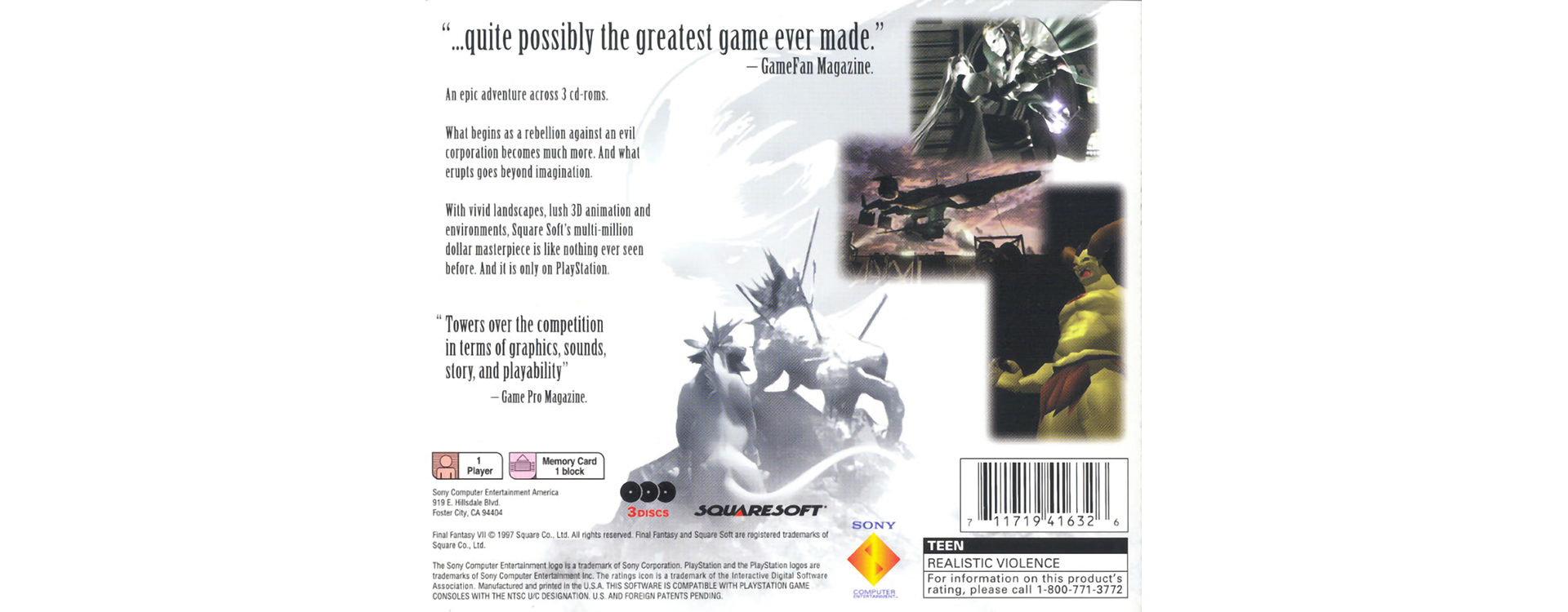

This approach of marketing by omission extended to the packaging, as well. Rather than sticking to a storyline synopsis like it did for prior Final Fantasy games, Square printed seven simple words from GameFan’s review: “…quite possibly the greatest game ever made,” along with a brief pitch and one more quote. It’s one of the more attractive and enticing backs of a game box ever made:

Credit: Square

A long way from Final Fantasy II’s box art, that’s for sure. Even here, the closest thing to gameplay is that brief glimpse of the Ifrit summon on the back of the jewel case.

The marketing paid off. Final Fantasy VII would be the first entry in the series to sell millions of copies in North America. But after all the money, all the FMVs, the localization, and the technological innovations, so much of the game remained functionally the same Final Fantasy experience Square had released several times over. Final Fantasy VII, in large part, was a new version of the same game that couldn’t crack a million in sales on the Super Nintendo. The underlying continuity was apparent from the moment the simple menu with its recognizable blue background, the same menu from the last two games, opened up beneath Cloud—an ATB bar, some hit points, and a familiar chime ringing in, asking for a battle command.

Final Fantasy VII sold roughly 10 million units during its PlayStation print run. Of those, 3.09 million came from North America, almost on par with Japan’s 3.25 million units sold. Compared to the hundreds of thousands of units managed by the game’s most successful predecessors, it’s safe to say Final Fantasy was no longer a series with a cult following.

In the wake of Cloud Strife’s journey, RPGs weren’t hidden gems. They were an accessible and, more importantly, lucrative genre. Furthermore, that $45 million budget set a stage for all video games, not just RPGs. Final Fantasy VII demonstrated that such a level of financial risk could pay off, even in a genre where the historical sales data indicated an uphill battle.

American gamers gave RPGs a chance. Finally, they got it.

Credit: Square, via MobyGames user Keeper Garrett

Past the Wasteland

Final Fantasy VII remains one of the most expensive video games ever produced, but it paved the way for other big-budget titles like Grand Theft Auto V and Destiny, games where a gargantuan investment could both yield a huge financial return and produce a memorable gaming experience. Had Final Fantasy VII bombed, it would surely be looked on as gaming’s Waterworld. Instead, it provided evidence that video games could be profitable on a scale previously unimagined. Following the game’s success, Square became a publishing juggernaut, and RPGs became far more accessible to audiences outside of Japan. In fact, saying a game was an RPG became a selling point. In more recent years, RPG-inspired mechanics have become almost mandatory in games of any genre, and while it would probably be a stretch to attribute that ubiquity to Final Fantasy VII, it’s also difficult to imagine it would have come about without a huge breakthrough RPG in the West.

The game’s story, as silly as it might seem today, grew to be cherished by so many that it helped inspire a revolution in interactive storytelling, one continued by narrative-heavy games like Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid. Now, story has become a huge fact of game criticism, and plenty of high-end games give narrative almost equal weight to gameplay.

In the more immediate aftermath, Square and Electronic Arts formed a partnership to bring the two companies’ catalogs into new markets. Games like Xenogears, which would never have seen western shores in the 16-bit era due to its antireligious overtones, received localizations. Meanwhile, in Japan, the agreement had Square EA trying to get America’s own best-selling genre off and running: simulation football. Despite publishing several years of the Madden franchise, things never really took off.

Enix’s mega-hot Dragon Quest returned to the United States in 2001 with Dragon Quest VII. It sold 200,000 units in North America—hardly world-breaking numbers, but enough to ensure the series would become a fixture of the American market once again. Niche RPGs like Valkyrie Profile and Grandia, the latter promoted as a “Final Fantasy Killer,” found their way to the United States. The mass of RPGs on the PlayStation gave the system a leg up over its competition, the Nintendo 64, and contributed to Sony’s victory in that generation’s console war.

Final Fantasy VII’s themes and aesthetic also helped to push RPGs to broaden their horizons. Shadow Hearts and countless other games took the RPG in new directions after Square showed it was okay to move away from straightforward fantasy tropes.

By 2007, Final Fantasy series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi had long left Square and was running his own independent studio Mistwalker. That year, Mistwalker released Lost Odyssey as an Xbox 360 exclusive. A throwback to the turn-based days of JRPGs, the game actually managed to sell better in America than Japan (though the fact that Xbox 360 sales were more than tenfold higher stateside probably had a lot to do with that). But many reviewers thought the game felt stuck in a time warp, a turn-based relic of the ’90s. Like many contemporary genres, the JRPG struggled to evolve and experienced growing pains, and it would take other influential titles to leave the classic Final Fantasy template behind and successfully bridge the gap to the modern day.

As a game, was Final Fantasy VII overrated? Maybe. In my eyes, there were much better JRPGs before it, and there have been much better JRPGs since. So much of the game was similar to the earlier Final Fantasy entries on the Super Nintendo, albeit with the fat trimmed and the added appeal of its sci-fi atmosphere and polished cutscenes.

But it’s also difficult to imagine what might have happened had Sony picked a different game—a sports sim or a platformer—for its massive 1997 marketing push. In all likelihood, RPG makers in Japan wouldn’t have had any example of massive success in the West to point to, and it would’ve taken longer for a big-budget title to prove to publishers worldwide that the risk could be worth it. The gaming industry as we know it today owes a substantial debt to Final Fantasy VII, not just for opening up a whole new genre of gameplay and storytelling to a wider audience, but for showing that the industry could support true blockbuster experiences.

Final Fantasy VII itself might be overrated, but when you look at what came before and what’s come since, it’s clear the phenomenon of Final Fantasy VII is anything but. More than 23 years on, as Square Enix launches a new chapter in the game’s legacy, the shadow of Midgar still looms large and undeniable.

Header image credit: Square

Patrick Holloway is a freelance writer based in Seattle, Washington, who fell in love with video games at age four. It all went downhill from there. He has written for GamesRadar, MSN News, and SB Nation. Follow him on Twitter @patoholloway for tweets on video games, the NFL, pizza, and 18th century literature. A large percentage of those takes will be absolutely tasteless.