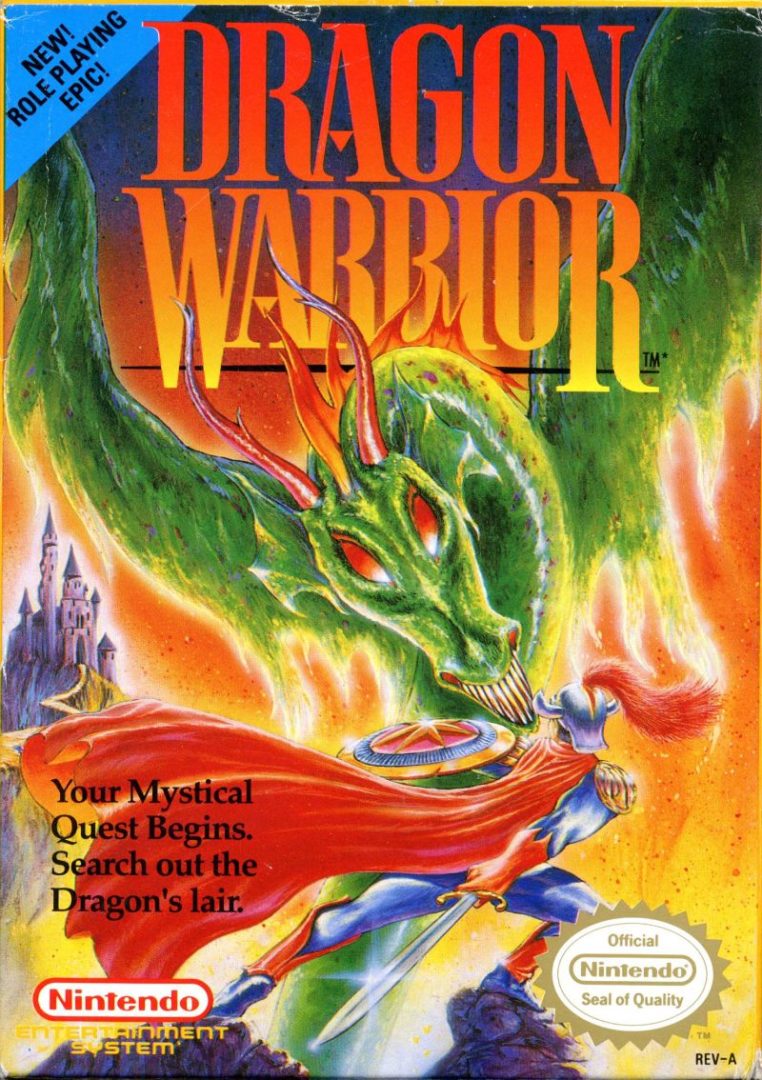

Sometime in 1989—the year the Berlin Wall fell, Taylor Swift was born, and The Simpsons debuted on Fox—I foolishly lent a friend my Dragon Warrior NES cartridge, with its fantasy-novel box art of a green dragon with elongated, Alien-influenced jaws rising above an armored swordsman in a flowing red cape.

“Your Mystical Quest Begins. Search out the Dragon’s lair,” the box copy instructed. “Sold,” said 10-year-old me.

Although I hadn’t yet beaten the game, I desperately needed someone to discuss it with, so I pushed the game on my friend with specific instructions not to sell any of my equipment or start a new quest—the game only had one save file, so anything he did would be permanent. Which led to a conversation that went like this:

“Hey _____, what do you think about Dragon Warrior so far?”

“It’s incredible! I love it.”

“Nice, what have you been doing?”

“Well it’s going great, I got you the copper sword.”

“…but I had the Flame Sword.”

“Oh. Is that one better?”

He knows who he is.

Of course, the pain of this ignorant betrayal will never fully go away, but that’s what happened when games only had a single damn save file. If you sold a weapon, it was gone forever, and if someone started a new game, your save file was toast. Gaming in the ’90s could be merciless that way. Hold in the RESET button before you turn off the POWER.

Three decades later (more if we’re counting from the 1986 Japanese release), it’s impressive how angry I still am about the forever-loss of the Flame Sword. But what’s more impressive is the enduring legacy of Dragon Warrior—known globally since 2005 as Dragon Quest, the name I’ll use for the rest of this story—and how great of an impact it’s had on gaming. It isn’t only that the series is in its 11th incarnation as Dragon Quest XI: Echoes of an Elusive Age, an entry that many hardcore fans have hailed as the best in the series. It’s how nearly every aspect of that first Dragon Quest—quests, monsters, weapons, and plot devices—has woven itself into the fabric of role-playing games, and some other, unexpected genres as well.

I played through the original game as a child, and picked up a remastered version recently for 5 bucks on the Switch store for a second playthrough. It’s important to realize that while Dragon Quest sold fairly well in North America, it initially struggled and was widely misunderstood—mainly due to it being the very first RPG for the Nintendo Entertainment System. The pacing was slow, and there were reams of text. At the time, many players expected every game to be a button-mashing platformer.

However, many of the core elements of the golden-age ’90s Japanese role-playing games that would follow in the original game’s wake are already present in this series’ first installment.

The story itself is quite basic, the stuff of a Dungeons & Dragons beginner’s quest. You are a stranger, newly arrived at Tantegel Castle in the world of Alefgard. King Lorik promptly tasks you with defeating the Dragonlord, who has stolen the Ball of Light, which is causing monsters to appear everywhere. Also, his daughter Princess Gwaelin has been kidnapped by a dragon—not the Dragonlord, but a different, minion dragon. (Sadly, Alefgard has many dragon-related problems.) Thankfully, it turns out you’re the legendary hero, descendant of Erdrick, so you should be able to square this away. After Dragon Quest, “monsters are growing bolder and attacking people because the mystical ___________ has been stolen!” would become de rigueur for RPGs, from Final Fantasy to Baldur’s Gate.

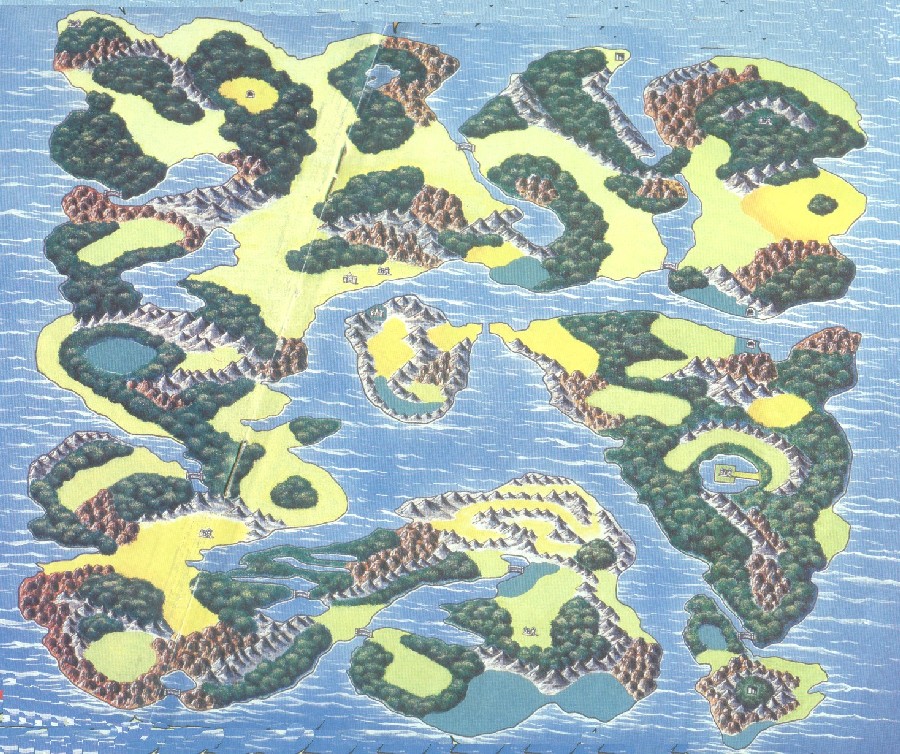

There is a world map for your avatar to explore, presented in an overhead perspective (Horii has often cited Richard Garriot’s Ultima as the inspiration for this aspect) which is dotted with dungeons and towns. Entering one takes you out of the “overworld” and into a new area map. There are plains, deserts, forests, hills, poisonous swamps, and impassable, jagged mountains. You have to speak to every villager in every town to make sure you know what to do next. I remember taking careful notes with a pen and a pad (“the fairy flute is 4 steps south of the fountain in the town of Kol”).

In Dragon Quest, enemies cannot be seen on the world map (which would quickly become another RPG trope) and randomly interrupt your progress; when you encounter one, the battles switch to a first-person perspective, and the fights are turn-based (combat was patterned on Wizardry). Your character has hit points, magic points for spells, some status-boosting items, and the ability to run away or parry. Defeating enemies grants experience points, and defeating enough of them increases your level, boosting some basic stats like strength, agility, vitality. It’s a bare-bones version of D&D stats, without anything so confusing as a THACO.

While the hypnotic “overworld” midi theme plays, my avatar crosses a bridge onto another continent, encountering a pink “Slimer” ghost who is for some reason wearing a witch’s hat, and I feel it—the same old pull of adventure and exploration, the need to cross another bridge, and then another, to wander to the very farthest shore of the map (it’s possible I also feel a wee tug of nostalgia).

Many credit Dragon Quest with being the true forefather of all JRPGs, but in some ways the game also embodied the infancy of open-world gaming on consoles. It’s an 8-bit game that came out over 30 years ago where the player can choose to go anywhere they want on the world map, right away.

Sure, if you strayed too far at an early level from where you were “supposed” to be, you would get killed by a Wolflord or a Demon Knight (crossing a bridge was a sure sign enemies were about to get harder). But technically, if you avoided enemies and (successfully!) ran away from them, you could wander as far into the world of Alefgard as you wanted—there was only one small, final area to “unlock.” It was actually possible to load up on Fairy Water (an item that warded away enemies), chug another bottle each time one wore off, and venture deep into territory that the pitiful hero, with his club and leather armor, had no business being in… and suddenly you’re being roasted for 9,000 hit points by a Magiwyvern.

Unlike most games from the era, Dragon Quest actually gives the player (some) choices. There are basically two major quests that King Lorik charges you with: save the princess, and defeat the Dragonlord. Of course there are loads of sub-quests and mystical MacGuffins like the Silver Harp and the Staff of Rain which you’ll need to progress (this is the great-granddaddy of JRPGs, so you’d better believe there are fetch quests, but it’s important to remember these were more innovations than cliches at the time).

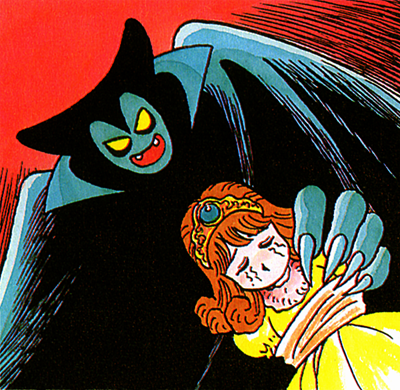

In order to save Princess Gwaelin, you’ll need to delve deep into a cave crawling with monsters and battle a green dragon. One spooky touch: In dungeons, a lit torch illuminates only those tiles immediately near the avatar, leaving the blackness hovering on the edges full of imagined horror. If the torch goes out, then you’re stuck in the dark, totally unable to see—a horrifying prospect worse than death, because on the NES the player would often be forced to hit reset and lose all progress; no one is likely to find their way out surrounded by total darkness.

But here’s the thing: You don’t have to go save the princess at all. The king is really happy about it if you opt to save his daughter, and there’s a little celebration for you at the castle, but there’s nothing stopping you from leaving the princess to stew in dragon-jail while you beat a path straight to the Dragonlord’s castle.

If you do save her, you’re given less choice later, when the Princess starts looking for some damn commitment and hits you with a shotgun-wedding proposal (right in front of the King, no less). The game does allow you to refuse her advances, and she will register her outrage at the hero’s abdication of his duty, but it becomes a dialogue loop with her saying, “But thou must!” over and over until you agree. Okay, it’s not exactly a dialogue tree, but in the ’80s this was still an impressive amount of input from the player. “The game wants my opinion? Hmm, I’m the greatest hero of all Alefgard, do I really wanna be tied down to this high-maintenance Gwaelin chick?” (My commitment issues began very, very early.)

Dragon Quest was unlike anything NES owners had ever played, which was a big part of its charm, but it did have peers. There was the long-running Phantasy Star series for Sega, which debuted the year after Dragon Quest and featured a mix of sci-fi and fantasy elements (as opposed to Dragon Quest’s straight-up sword and sorcery). Miracle Warriors came out for the Sega Master System the same year, and is arguably more advanced in some ways, most notably in that it gives the player a party of four, as opposed to a single protagonist. But in other, more important ways, Miracle Warriors is clunky and obtuse; for instance, navigating the world map in first-person is a chore, and the player is often left with no clue about what to do, where to go next, or what spell to cast.

So what made Dragon Quest such a breakout, and the true prototype of the JRPG as we know it today? The best answer is the magnitude of the core talent involved: series creator Yuji Horri, artist Akira Toriyama, and composer Koichi Sugiyama.

Horii is a gifted storyteller, and had been personally involved in every main series entry since; the staying power of the series is a testament to the strength of his vision—many of the games’ plots aren’t particularly original, but the episodic nature of the subquests and the little stories from each NPC and village are his strong suit. Toriyama was already one of the most famous manga artists in Japan by the time Dragon Quest was released (although still years away from becoming a global phenomenon), so even though the actual in-game art and designs were limited by the 8-bit console, his Dragon Ball–style artwork on the box would have commanded attention from Japanese gamers. And Sugiyama, a classically trained conductor and composer, is regarded by his peers as one of the most influential game music composers ever.

Horii has often mentioned how his goal was to take a genre with a notoriously high barrier to entry (numbers, math, dice-rolling, reams of text, etc.) and make it more accessible and inviting for a wider audience. In a 2011 interview with Gamasutra, the designer said that his objective “is to make the games intuitive and accessible for anybody. I’m the kind of person who doesn’t read the manual before playing a game, so I want to make sure the game is simple, with simple controls—but you can still have complex action, and enjoy the gameplay. I wanted to include humor in the games, so the people who play can actually really enjoy it and have laugh-out-loud moments.”

Horii’s genius was in how he simplified the concept of RPGs in general and highlighted the parts that made them so much fun. It was also evident in his talent for world creation and penchant for employing mythology.

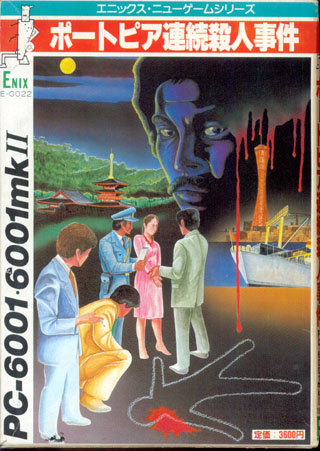

And Horii’s earlier hit for PCs, The Portopia Serial Murder Case, is as much an influence on Dragon Quest as anything else. This early visual novel/murder mystery game featured innovative nonlinear gameplay, first-person graphics, a primitive open world, branching dialogue choices, and even a dungeon maze.

Of course, the Dragon Quest series has evolved, but in many ways it has stayed true to its roots. The core elements and the tone of the in-game world never really change—they just get an upgrade, the games get longer, and the stories go deeper. It’s a stark contrast to its rival and sister series, Final Fantasy, where, while some elements do carry over from game-to-game, it’s very possible for one sequel to look, feel and play completely differently from another. Dragon Quest is more concerned with tradition and lore. It’s been called the “comfort food of RPGs.”

Horii has never stopped being involved in the series, and his vision for the games hasn’t been compromised, which is a part of the reason why the games have endured for three-plus decades. It’s why he’s bigger than Jesus in Japan. (Okay, bad example in a country with a population that’s one-percent Christian, but you get the idea.) There’s even a statue of a slime in Horii’s birthplace of Sumoto, Japan. But do Dragon Quest’s true roots really lie outside of video games altogether?

Jonathan Padua, author, veteran gamer, and PAX East panelist (on “The Mythology of Games: Why the Legend of Zelda is just as important as the Legend of Beowulf”), sees JRPGs as either heavily influenced by or straight-up homages to the classic Dungeons & Dragons tabletop game.

“The dice and notepads were replaced by a program, the DM-created interactions with the NPCs were replaced by script and dialogue paths,” Padua told me. “The gaming console streamlined the process, making it quicker and easier for a beginner to access,” but Padua noted there were also sacrifices. Gone were “a lot of the creative aspects that make D&D persistent today… the narrative backstories made by the players, the inventive quests and dungeons made by a good DM. The most striking change was the erasure of player interaction. Long hours at a gaming setup with your party were replaced by long hours in front of the TV.”

Padua pointed out that the collective aspect eventually made its way into video games with Ultima Online and World of Warcraft, but that with Dragon Quest, “the same experience was played across the world, but it was mostly played alone. The experience, not the game itself, was the shared bond.”

However, Padua believes that “in bringing the games to a new platform, and a new, nascent audience, Dragon Quest would be the gateway back to traditional tabletop gaming. Most of the people I know who actively play D&D today claim their first experience was not from a tabletop experience, but through a love of JRPGs.”

The other heavyweight talent involved in Dragon Quest, the lead artist and character/monster designer, was a 30-year-old Akira Toriyama. Toriyama, a prodigiously gifted artist, also created a fairly popular manga series called Dragon Ball, which spun out into a globally popular anime that you may have heard of.

No one has defined the look of the Dragon Quest games over the years more than Toriyama, and no one has had a greater influence on the visual style of JRPGs, either. In fact, his chibi artistic style of big eyes and big heads on squat little pixelated sprite bodies became a sort of visual shorthand for the entire genre—if you saw those smushed-down little pixel people on the screen, you knew what kind of game someone was playing.

Toriyama’s monsters also helped set Dragon Quest apart from its peers. His Wraith Knights were skeletal and sinister, and his Magicians were cloaked and intimidating, their eyes shining beneath their hoods in a way that foreshadowed Final Fantasy’s Black Mages. But some enemies that would go on to become mainstays of the series were kind of… cute. The Slimes were actually smiling at you as you hacked away at them, and the Drakees looked more like pets than something wicked.

For added perspective, I induced a fellow RPG fan who’d been too young to encounter the original Dragon Quest to give it a play-through. Ryan Harris, writer and host of Nerd Alert! Trivia, saw things I didn’t.

“My mind kept drifting back to another one of Japan’s popular franchises, whose core DNA seems inextricably linked to DQ: Pokémon. Dragon Quest really makes itself about one thing: exploring a world and battling monsters.”

Harris noted the quests to fetch magic items make up very little of the player’s in-game time, and that the vast majority of Dragon Quest is “a laid back, casual grind against a never-ending onslaught of cute monsters. So as a kid who was obsessed with Pokémon Red and Blue, the core mechanics felt instantly familiar—the fun of exploring an open world littered with blind, wild monster encounters that pop off like landmines every few seconds, the thrill of the encounter, wondering what cutesy monster was going to try to murder me with a smile next, the endlessly maddening and repetitve battle music—it’s all there.”

He admitted that the comparison may be more obvious now that Square-Enix has released its own Pokémon Go clone, Dragon Quest: Walk, in Japan. Still, he said, “There is no denying that Slimes are the primordial ooze that Ratatta climbed out of.”

The cutesy monsters are a feature that’s remained constant throughout the series, and fit the lighter tone of Dragon Quest in general. You won’t find characters in the series, say, attempting suicide by leaping from a beachside cliff (looking at you, Final Fantasy VI). It’s not that nobody can die—they can and do—but there’s a certain line of darkness that Dragon Quest doesn’t typically cross, so the “monsters” that look more like Furbies jibe with the general theme.

Horii spoke about the series’ tone in an interview with Polygon in 2018: “We were really careful about how we presented defeating monsters. We never say, ‘You killed the monster.’ It’s always, ‘You’ve defeated it.’”

Incredibly, the game’s North American release toned down Toriyama’s influence. It’s a bit like if the 1990s Chicago Bulls played an exhibition game in Asia and decided to bench Jordan. His art was taken off the box, out of the instruction book, some of his in-game designs and writing were altered, jokes were removed.

According to Horii himself, it sounds like Nintendo of America thought at the time that the cutesy, bug-eyed people and general goofiness would be a turn-off for Western audiences, who would think it corny. In the same Polygon interview, Horii said, “We discussed it with Nintendo and they mentioned that the perception of anime at that time was very childish, so it might not be the best approach. I guess there was an inclination and a desire for more realistic artwork in North America and Europe, and that’s the argument that they had presented.”

Maybe they were right: The change of art and tone made for an adventure that had an Arthurian tone and a closer feel to Dungeons & Dragons, something that American players in the ’80s would know about and associate the game with. And it isn’t as if Nintendo was alone—everybody was doing this in the ’80s and well into the ’90. Even the box art on Street Fighter II was made to look “less Japanese.” It would be many years before the localized North American series fully embraced its Japanese roots.

It’s impossible to discuss the game without including its iconic score. Composer and conductor Koichi Sugiyama is an industry legend, and has composed the music for every single entry in the main series (as well as most of the spin-offs, like Dragon Quest Builders) along with loads of other Japanese anime, movies and TV shows. The game’s trumpet-blast theme music is instantly recognizable to fans. Hell, it still manages to be stirring and inspiring in its original 8-bit chiptunes format, and in Dragon Quest XI, where it’s performed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, it’s nothing short of breathtaking. Nobuo Uematsu, composer for much of the Final Fantasy series, has cited Sugiyama as an influence, and described him as “the big boss of video game music.”

The overworld theme, while brief, is melodic and almost meditative, urging the player onward into the unknown. I hear it in my mind every time I’m exploring a valley or hiking a forest trail in real life. I’ll take a pass on the “battle theme,” though—as the enemy encounter rates for the original game were notoriously high, I’ll be hearing it in my head until I die.

Still, while a breakout smash in Japan, the game struggled overseas, and didn’t exactly light the North American market on fire right away; when the port became available on the NES in 1989, my friends almost uniformly hated it.

“There’s too much reading! I don’t want to read a book, I want to play a game,” was a common gripe among the crew, most of whom favored action-adventure and wanted to “see” the character striking the enemy. I still maintain this reaction was because they A) lacked imagination and B) were slow readers, but I digress. Being forced to read all the Old English probably didn’t help (“Fortune smiles upon thee… thou hast found the Death Necklace!”).

Despite being so unfamiliar (most U.S. console gamers couldn’t have told you what the letters “RPG” stood for in the 1980s), it did break through—partly because Nintendo cooked the books a little, giving away a free copy of Dragon Quest with every subscription to Nintendo Power, the official print magazine of the company. It sold 500,000 units in North America (about one-third of what it sold in Japan). The series wouldn’t come close to that number overseas until nearly 20 years later, when fan-favorite Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King came out for the Playstation 2 in 2004.

While transformative, Dragon Quest is far from perfect. The game demands that you navigate a cumbersome menu in order to do almost anything—open a door, speak to a villager, search the ground, etc. It’s grindy, forcing the player to spend hours and hours in the wilderness fighting monsters and leveling up. Every town sort of looks the same, and the enemy encounter rate can be maddening. The storyline is wafer-thin, and by the time of the localized North American release, graphics had moved on.

And yet, there was a quality of enchantment surrounding the game: the collective of towns and the illusion of a connected society, the sense that the citizens of one town were going about their lives while you journeyed to the next, the thrill of encountering a new type of monster in the overworld, the rhythm of the town-overworld-dungeon cycle, and the storybook atmosphere—it all synced up to create the first true role-playing experience for the NES, and one of the most important games ever created.

It’s a rare game that cuts across generations—fans of the earliest games are now parents, and sharing the new releases with their kids. In the 2011 Gamasutra interview, Horii noted that the team created a multiplayer mode for Dragon Quest IX because “we found lots of people saying they played together with their parents or kids… so if they had the multiplayer, the son can play with the dad and be like, ‘Oh Dad, come on, we’re going this way!’”

Just one year after Dragon Quest, the original Final Fantasy arrived for the NES and, truthfully, surpassed the earlier RPG. The player controlled a party of four, there were multiple character classes, unique skills, tons of magic spells, the world was bigger, there was a boat and an airship, the story was far deeper and involving, and most importantly, if you chose a thief you could level him up into a ninja. Regardless, the overworld, the combat system and much of the plot were cribbed from Dragon Quest. In the English-language NES version, the game even seemed to acknowledge this debt, with a tombstone for “Erdrick” in one town’s cemetery.

Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy were both revolutionary games, and each would go on to become a successful, long-running series. But before the great merger of 2003, SquareSoft and Enix were rivals, seeking to outdo each other’s last release with each new installment. However, some key creative talent from each studio would come together, years before the merger, for a very special project.

That project was a game called Chrono Trigger, released in 1995 for the Super Nintendo. Square assembled what it dubbed its development “Dream Team”: the game featured the combined creative powers of Horii, Toriyama, and Final Fantasy series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi, among many others. The term gets overused today, but the comparison was apt—the results were much the same as putting Magic, Larry, and Michael on the same basketball squad. Chrono Trigger was, naturally, a masterpiece, and is widely considered to be the greatest RPG ever. Transcending genre, it regularly ends up on lists of the greatest video games of all time.

The Dragon Quest series alone would be enough to land anyone in the video game hall of fame. Chrono Trigger merely cemented the near-mythological status of Toriyama and Horii in the gaming industry. And like Final Fantasy, Earthbound, Lufia, and every other RPG since, it’s important to remember that it stands on the pixelated, squashed-down shoulders of the original Dragon Quest.

All images: Enix/Square Enix

Stephen K. Hirst is a freelance writer living in Cusco, Peru. He likes video games, basketball, Buffalo wings, and comics. His work has appeared in Slate, Rolling Stone, Bedford & Bowery, VICE News, The Huffington Post, and Salon. He will ruin you at Twisted Metal 2.