In November 2016, Greenpeace tweeted triumphantly about Vietnam’s decision to scrap its long-held plans for two nuclear power plants, the statement vaguely gesturing toward renewable sources. This naive display was greeted with hundreds of derisive responses, a barrage uncommon even on that unfriendliest of social media platforms. What the world’s premier environmental organization somehow failed to deduce—and what other Twitter users were so eager to point out—was that if one of Asia’s fastest growing economies couldn’t fulfill its energy needs via cheap, clean, and only potentially hazardous nuclear power, it would do so via expensive, polluting, and otherwise assuredly destructive coal-based methods. Which, of course, it did.

For decades, nuclear power has held a fearful grip on the popular imagination. Never mind that nuclear accidents are exceedingly rare or that their impact is dwarfed by the environmental damage caused by coal. They’re spectacular and make for good horror stories—a sudden failure that could have thousand-year consequences. If overblown fears of an irradiated planet are powerful enough to twist the response of an ecologically minded organization so that it celebrates developments it should be deploring, imagine how ripe for exploitation those fears could be in the hands of an entertainment industry that, since its inception, has thrived on spectacle. In the late 1970s, all the nascent medium of video games needed was a nudge.

A more ominously timed cinematic release than The China Syndrome may be hard to find. The high profile thriller about security cover-ups at a California nuclear plant opened in theaters on March 16th, 1979. Twelve days later, a cooling malfunction escalated into the highest profile nuclear incident in U.S. history: a partial core meltdown at the Three Mile Island facility in Pennsylvania. While the average local exposure to radiation has been measured as equivalent to a typical X-ray, this was still seen as a major disaster, its infamy doubtlessly enhanced by Hollywood’s uncanny portent.

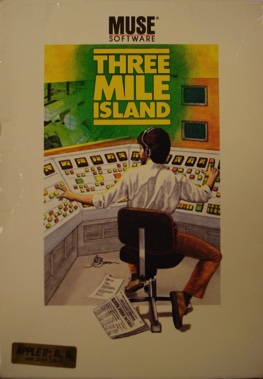

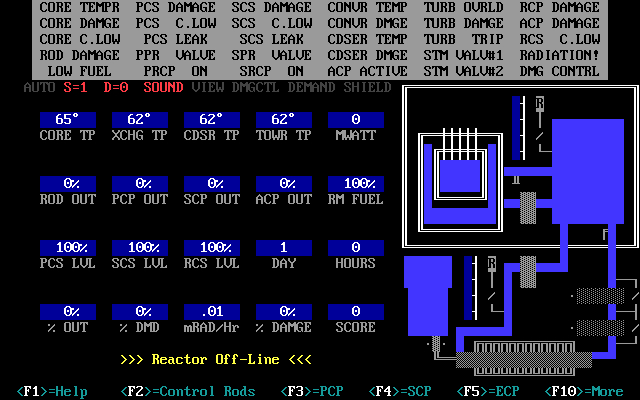

Video games pounced, and the first title to capitalize on public unease came out before the year was through. A sedate simulator for the Apple II, Muse Software’s Three Mile Island, puts you in charge of the titular power plant, monitoring temperatures, adjusting control rod positions, and scheduling maintenance. Despite its sensationalist subject matter, this was a level-headed, deeply technical game, its diagrams and counters completely impenetrable to players that hadn’t familiarized themselves with its dense 35-page manual. Packaged with an inconspicuous cover of a technician operating a seemingly untroubled control panel, nary a hint of impending doom in sight, it was proof that that the medium wouldn’t stoop to embarrassing lows in order to grab public attention. At least not yet.

Three Mile Island was the first in an unlikely simulation subgenre, one nurtured by the widespread anxieties of its era. A year after Three Mile Island’s debut, Nuclear Power Plant was released for the Commodore PET; then, in 1981, strategy legend Chris Crawford developed the somewhat more imaginatively titled Scram for the Atari 8-bit computers. A brief lull followed while the world’s attention turned elsewhere. But the radioactive spectre would emerge again in the spring of 1986, feeding off the fear of millions awaiting the slow drip of information from Ukraine with bated breath. By then, the medium had changed, and so had its marketing practices.

American publisher Cosmi and its ever controversial European distributor US Gold could not let the opportunity pass them by. Paul Norman’s Chernobyl (1986) may have been yet another complex, painstakingly researched simulator based on a genuine desire to understand the disaster. But its title alone (to which Norman objected), not to mention a kind of promotional art that foregrounded a blazing communist insignia and workers being blasted away by the force of an erupting nuclear core, spoke to unprecedented levels of crassness for a tragedy that was only a few months old and whose extent was still under debate. Even the usually apolitical gaming press of the time were compelled to criticize the tastelessness on display, the game’s Zzap! 64 reviewers describing its packaging as “inappropriate,” “silly,” and “gruesome.”

Credit: D. Gottlieb & Co.

Endless number crunching and headache-inducing spreadsheets aside, there were other, livelier, ways that the medium coped with the hot topic of nuclear energy in the mid 1980s. Reactor (1982) is a fast-paced arcade game where you play goalkeeper, blocking waves of bouncing subatomic particles from reaching a core and causing an explosion. Countdown to Meltdown (1984) is a sprawling action/strategy hybrid in rudimentary 3D that puts you in control of eight androids with different skills in an effort to avert the overheating of a plant’s central core. Uncle Henry’s Nuclear Waste Dump (1986) is a smart inversion of match-3 puzzle mechanics tasking you with stacking barrels of nuclear waste while ensuring similar containers do not come into direct contact. And Nuclear Bowls (1986) is a traditional action adventure where a mission into the depths of an abandoned power plant, with its sinister funnels choking the stars in a striking splash screen, pits you against malfunctioning robots, security drones and, inexplicably, giant porcupines. With the modest technology available at the time, thematic conceits were not meant to be meaningfully explored in action games. They were interchangeable narrative trappings deployed to visually differentiate them—or, more frivolously, provide material for a fancy cover and blurb.

Still, behind the blocky graphics and basic stories of the era one could sometimes glimpse the vague outlines of a position. In most cases the underlying attitude toward nuclear energy was fear or at least suspicion, though whether that was an uncritical echo of popular opinion, a conscious intervention on the debate, or simply an easier pitch for sensationalist promotion is hard to gauge. Positive takes, while rare, still existed in games like Nuke Lear (1984) which envisages a 21st-century Earth where all energy problems have been solved and the only worthwhile job left (yours, incidentally) is directing radioactive waste traffic through a series of interconnected pipes. Isometric adventure Chain Reaction (1987) adopted a more combative stance, casting the Anti-Nuclear Party as aspiring saboteurs, and yourself as the laser gun-toting, jetpack-sporting hero out to stop their villainous plans.

It is hardly surprising that most games dealing with the subject of nuclear energy were produced in the mid 1980s, right before and after Chernobyl. The discourse had always carried, alongside genuine fears of an accident, the marks of Cold War paranoia, and while the Pripyat disaster did not inaugurate either, it acted as the perfect vessel for both. Nevertheless, by the time The Oakflat Nuclear Power Plant Simulator, the last of that subgenre’s major examples, was released in 1988, Chernobyl had been long replaced as front page news and the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse. While gaming was increasingly enamored of irradiated steppes and rabid mutants, it started seeking their origins elsewhere. Armed nuclear conflict made for sexier backstories than industrial accidents and it came with built-in advantages: clearly delineated sides and reasons to fight. Thus, the groundbreaking RPG Wasteland (1988) paved the way for a spiritual successor, Fallout (1997), that blossomed into a multi-billion-dollar franchise, Metro 2033 (2010) became one of the most recognizable single-player FPS of its generation, and—barring the occasional asteroid strike or zombie epidemic—the term post-apocalyptic was largely understood to refer to worlds scarred by atomic warfare.

Credit: Gamtech Software

But since the 1990s, the hazards and benefits of nuclear energy have been mostly sidelined as a recurring theme. Granted, certain hallmarks and associated tropes have been sporadically utilized for side missions, like the relocation of a volatile reactor in PlayStation shooter Soviet Strike (1996), or Call of Duty’s clockwork return to Pripyat for a jaunt under its emblematic Ferris wheel. Even in the rare instances where the issue takes center stage, it’s often in service of a preexisting backstory, like in mobile title The Simpsons: Minutes to Meltdown (2007), where Homer races against time to turn the valve that saves Springfield.

Credit: Activision

Strategy is probably the only genre where nuclear plants have consistently found a home, though it hasn’t been a particularly welcoming one. Extending the medium’s alarmist tradition (or, more pragmatically but no less misleadingly, accounting for game balance), SimCity typically presents them as more malfunction-prone than a ten-dollar hair dryer, while Civilization VI: The Gathering Storm seems unable to differentiate between a leaky core and the A-bomb.

Arguably the only high-profile game to revolve exclusively around the side effects of a nuclear accident in the past 30 years has been S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Terrifying and fascinating in equal measure, its memorable Zone, formed as a result of a second Chernobyl explosion and teeming with mysterious phenomena called anomalies, captures our ambivalence toward the issue more accurately than any other setting.

Credit: The Farm 51

It’s an indictment of our media-obsessed times that, while the real-world tragedy of Fukushima in 2011 failed to generate interest on the subject of nuclear energy by developers, the frenzy surrounding HBO’s high-profile Chernobyl miniseries, finally, after decades of indifference, did. A quick Steam search reveals a ridiculous statistic: Out of 21 games bearing the tag “Chernobyl,” 13 have either been released in 2019 or are currently in production, a motley assortment of point-and-clicks (Failed State), isometric open worlds (Chernobyl: The Untold Story), a first-person survival game (Chernobylite), and at least three attempts to simulate the containment efforts of the 1986 disaster. A deceptively hyperbolic entertainment product turned nuclear power into the topic du jour once again, and it is doubtful that video games, in their rush to exploit it for narrative padding and maximum marketing synergy, will fare better than they did in the 1980s.

What has definitely changed since then, however, is a growing urgency for environmental action and a new awareness of video games as an active influence on sociopolitical discourse. Calling out the medium on its cheap demonization of an accident that had infinitesimally smaller impact than the millions of lives affected by coal annually should not mean that we don’t get to revisit those irradiated wastelands ever again—only that we owe it to ourselves, and the planet, to take a more honest, less sensationalist look at nuclear power.

Header image: Chernobylite, The Farm 51

Alexander Chatziioannou is a writer living on a small Mediterranean island. He is interested in the historical evolution of videogames as a medium and his work, on that and various other subjects has been featured in The AV Club, Slant Magazine, Eurogamer, and Kotaku UK, among others. Hates nostalgia, loves old games.