The secret to game design, Dan Pinchbeck says, is dinosaur poop.

“A friend of [my wife and I] came to stay with us years ago, and we were watching Jurassic Park III,” the creative director of The Chinese Room tells me in a café just outside the studio’s office in Brighton, U.K. “There’s a bit where the guy who’s carrying the satellite phone gets eaten by the Spinosaurus, and there’s no way off the island at all. Then they find a big pile of Spinosaurus poo, and hear the phone ringing. [Alan Grant] sticks his arm in and pulls out the phone.

“We all went: ‘Oh, come on!’ This friend of ours turned around and said: ‘What, you’re prepared to accept dinosaurs on an island, but you can’t accept that?’”

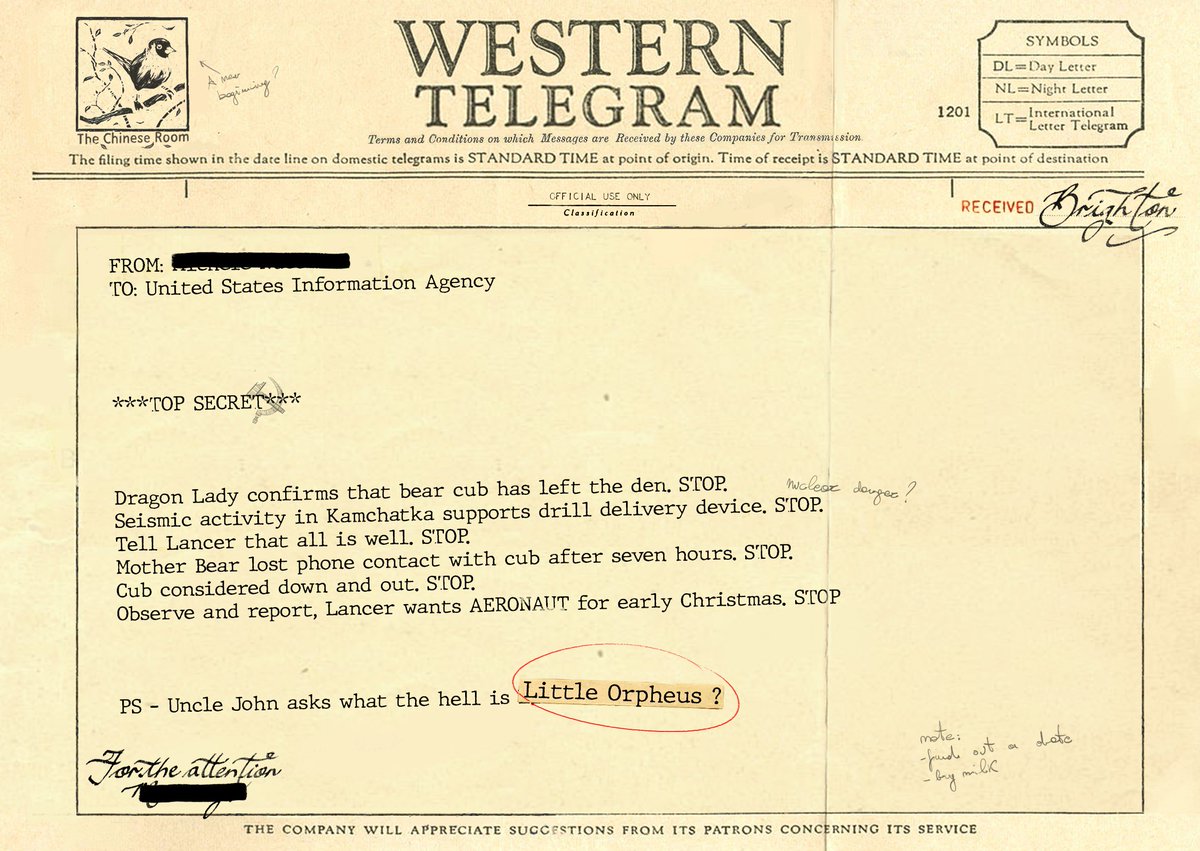

Whenever The Chinese Room needs to decide how bold to be with Little Orpheus, its upcoming Apple Arcade exclusive and its first game since being bought by Sumo Group, Pinchbeck simply uses one phrase: dinosaurs on an island. “Can we do that? Dinosaurs on an island. We’re making a game about a Soviet cosmonaut going to the center of the earth—if you’re prepared to accept that, the sky’s the limit… You don’t find out where the line is by tip-toeing towards it. You’ve got to bomb past it at full speed, realize you’ve shot past it, turn around, and go back and find it.”

Pinchbeck hopes this brave approach will define The Chinese Room’s rebirth from its own ashes. The studio behind Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture went dark in 2017: Pinchbeck and his wife, studio co-founder Jess Curry, didn’t have enough cash to keep it going, and laid off all eight of the development staff. After taking time to recharge, they sold the studio to Sumo Group, the parent company of Crackdown 3 developer Sumo Digital, last year.

Pinchbeck started solo within Sumo, but now The Chinese Room is around 35 strong, and Pinchbeck is finalizing plans to move to a new office that could accommodate double that number. That rapid growth is matched by his level of ambition. He wants to be spoken about in the same sentence as Arkane Studios and Ninja Theory—The Chinese Room could even become “the Naughty Dog of the U.K.,” he says, not necessarily because of the types of games it makes, but because of its focus on storytelling and its consistent level of quality. “That’s not me being arrogant. I’m not saying we’re there yet. But that’s where [we] want to be.”

So how does he intend to make The Chinese Room, all but dead two years ago, into one of Britain’s best studios? What has he been working on since the Sumo deal? And what has he learned from the ups and downs of the company’s past?

“I want it to be so if we make an FPS, you play it and you go, ‘That’s a FPS that only The Chinese Room could make.’”

One of the big differences between The Chinese Room now and five years ago is the absence of Curry, who was co–creative lead on the studio’s last major release, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. She now presents a show about video game music on BBC Radio 3, among other projects. “I really miss working with Jess,” Pinchbeck says. “I’d just put an idea in front of her, look in her face and go, ‘No, you’re right, that’s a bad idea.’ That shorthand is really important.

“I think we’re quite a good mix. I’m quite hyper: I’ll come up with 1000 ideas, 990 of which will be shite. Jess will come up and say, ‘It’s [those 10].’ She’s really, really good at just seeing the target. I trust her creative instincts so completely.”

That’s not to say they always agreed during the development of Rapture or other games—but when their opinions differed, Pinchbeck was able to separate the “emotional side of it and the creative, professional side,” he says. “Sometimes there’s really painful decisions and painful discussions, because you care about it. Maybe it’s amplified if you’re married to that person, but it’s kind of the same with anyone you’re working with.”

While Pinchbeck misses working alongside his wife, he doesn’t miss the impact running a business had on their relationship. “The challenge if you’re working with your partner is work-life balance, and that’s difficult enough in games… You try to avoid bringing business stuff home, lock it off at the end of the day and not go, it’s 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock at night and we’re talking because we’re worried about finances or HR,” he says.

“If it’s your studio, and the alarm goes off in the building at 3 a.m., it’s your phone that rings. If it’s a member of staff who has a crisis in their life, it’s you. If you fail a milestone, it’s on you, if the money doesn’t stretch, it’s on you… You’re learning a lot as you go. You don’t always have solutions, you make mistakes, you don’t always do the right thing. It’s a different kind of pressure, and it’s not one that I think either of us miss. It got to a point where we were like: We want to get our marriage back, and not just be business partners, and not every conversation had to be about a problem.”

The decision to sell was also motivated by a desire to refocus on the creative side of game development. “One of the reasons we sold and joined Sumo was going, ‘If we’re going to talk about games, it’d be nice to talk about the games we’re making, as opposed to administrating those games.’”

Some of those stresses came to an end in September 2017, nearly a year before the acquisition, when The Chinese Room laid off all eight of its staff and the couple swapped their office for their home. Pinchbeck spoke about that time in a 2017 Eurogamer interview, and isn’t keen to dwell on it further. “I don’t mind talking about it, but I don’t think there’s a lot to be added,” he tells me. “We hit a bump in the road, like a lot of studios our size, we had to make tough choices, like a lot of studios our size, and we tried our best to get through it.”

It was the right thing to do in the circumstances, he says, and the fact that most former staff members were able to find jobs quickly “took the edge off.” But it was still a “really, really dreadful time” for him and Curry. They were also both burnt out after working nonstop for half a decade. “We’d been pushing ourselves and pushing ourselves for five years. That’s not sustainable for anyone in any industry.” They needed time to recover, heal, and pursue fresh ideas—some of which The Chinese Studio is working on today.

That five-year stretch of uninterrupted work began during the development of Dear Esther, originally spawned from an academic research project. Pinchbeck says he was obsessed with pen-and-paper RPGs growing up, and always wanted to work at Games Workshop. Instead, his jobs varied from choreographing fights in open-air theaters to marketing for arts organizations, and he eventually ended up at the University of Portsmouth in a new department that was half artists, half scientists.

He soon grew tired of academics writing papers about what games could and couldn’t do without putting their ideas in practice. He wanted to conduct more hands-on research, and secured a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council to make three projects based on what, he presumed, were not commercially viable ideas. They were the pacifist Doom III mod Conscientious Objector and two Half-Life 2 mods: the gravity gun sports game Antlion Soccer, and Dear Esther.

“Esther was coming from things like System Shock 2 and S.T.A.L.K.E.R.,” Pinchbeck says. “It’s always been FPSes for me, ever since Wolfenstein [3D] and Doom. I thought, ‘Those moments, where it’s just quieter, where it’s just you in that space, they’re powerful, there’s loads of atmosphere, and it all comes down to a really emotional response. What if a game was just that?’”

He says his group of researchers were unfairly portrayed as a “ranting, flag-waving” band who wanted to fix what was wrong with games. “It always used to hurt my feelings,” he says. “I love games, there’s nothing to fix in games. It was just about going, ‘I think there’s this really interesting space just to the left, where nobody’s probably going to go because it doesn’t feel like it’s commercially viable.’”

Credit: The Chinese Room, Robert Briscoe, Curve Digital

Dear Esther stood out among the trio. After gaining traction in the Half-Life 2 modding community, Pinchbeck and Curry released a commercial version on Steam, and watched the sales roll in. “It was late at night, and we’re sitting there hitting refresh on Steam, and the numbers just started clocking in. ‘Here’s the first hundred… There’s an extra zero on that.’ 1,000, 10,000, clocking, clocking. And we’re sitting there watching it going, ‘That’s completely nuts.’ We eventually went to sleep, woke up in the morning and we’d paid off the investment. We were in the black in a night. It just kept going and going, it was really unreal.”

At the time, they didn’t realize how life-changing the moment was, and they never had time to take stock of what they’d achieved, Pinchbeck says. They flitted from Dear Esther to Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, which they made for Frictional Games, and then onto Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, published by Sony and produced by Sony Santa Monica. It was only when they signed with Sony that the team quit their university jobs.

It was a wonder Sony wanted to sign Rapture all, Pinchbeck says: The team envisaged an open-world version of Dear Esther and knew some of the folks at Santa Monica, but the prototype they sent to Los Angeles was ropey. It was built using a loaned CryEngine license, and visually wasn’t even up to the standard of a game jam creation, he says.

“We sent them what I thought was a game design document, which is laughable, because it was so sketchy. We had this very, very rough gray-box open world with a bunch of stuff scattered on it, going, ‘You could sort of do this and this, and this could sort of happen.’”

But the bones were there: a pub in the British countryside, with benches arranged around trees, and music that layered in as you approached objects. Combined with the art from long-time concept artist Ben Andrews, it was enough for Sony to take a “leap of faith,” in Pinchbeck’s words. He believes Rapture fit with the company’s desire to become the home of experimental console games ahead of the PS4’s launch, and that it helped Journey was in full production at the time.

Although the game went on to sell well, making it wasn’t the happiest of times for The Chinese Room. Curry has spoken of her “desperately toxic relationship” with her publisher in the past (without naming Sony), and Pinchbeck has said how relationships with Sony drifted. Now, rather diplomatically, he says it’s “water under the bridge.”

“We’ve got a really good relationship with Sony now. Sometimes things just go south a bit, and you have to deal with it.”

Following Rapture, and shortly after the release of the team’s next game, a Google Daydream VR project called So Let Us Melt, Curry and Pinchbeck hit the brakes and moved the studio home. For the six months that followed, they purposefully did nothing much in particular. It was a time to recover from their burnout, get back to married life, and unearth some ideas they could be excited about. “It’s little things like getting weekends back, and not being technically at work. Being able to say, ‘There isn’t a company to think about,’” he says.

“It was good to go, ‘There’s a no-pressure creative outlet where the only person that’s going to be bothered if you haven’t written anything today is you.’ And recharging, just having the chance to go, ‘What are the ideas?’” One of those ideas turned into a novel that Pinchbeck has just about wrapped up, and it may well become the studio’s next game.

The idea of selling the company cropped up during this time, and the couple met with Sumo Group co-founders Carl Cavers and Paul Porter. “We really liked them, went, ‘These are good people, they care in the right direction, they’re trying to do the right thing with this company, we can work with them.’ If we hadn’t felt that, if there had been red flags going off left right and center, we wouldn’t have joined,” he says.

Pinchbeck liked the idea of having a support network and a structure around him to ease development pressure. As part of the deal, he made it clear he wanted someone else to run the business side of the studio so he could focus on new ideas. He got Ed Daly, who previously worked in director roles at various game studios and tech companies, to join as The Chinese Room’s new studio director.

Now that Pinchbeck has started working for a larger company, he’d never go back to running his own, he says. “It’s too much. The last game we made, the team were left without me for huge chunks of it because I was desperately trying to line up the next title. That’s no fun. It’s not fair on the team, if you’re supposed to be creative director and you’re only [there for] 40 percent of what they’re doing.”

He’s said in the past that he’s “uncompromising on creative control,” so is he uneasy now about answering to a larger company? “It doesn’t worry me at all. [Sumo’s] view is: ‘What would be the point in acquiring The Chinese Room and having them not be the The Chinese Room?’ They have high expectations, and I want them to have high expectations for what we produce, because I think we should be pushed and challenged. I enjoy that, I relish that.”

He also enjoys working with other creative directors, because running a small studio was “isolating” at times, he says. “It’s nice to be part of a group of people going in the same direction… I feel so much more creatively revitalized as a result of taking that break and making that move. It hurt, but it was worth it. I’m really excited at the moment.”

He was the sole member of The Chinese Room at Sumo Digital following the acquisition last year—by that Christmas, the studio had most of its lead developers in place. The headcount is now up to the aforementioned 35, split in two: one team for Little Orpheus, and one team to work up future projects, of which there are many in the pipeline.

promote the upcoming Little Orpheus.

Credit: The Chinese Room

Orpheus is a statement of intent; it’s the studio clearing its throat ahead of what’s to come. Pinchbeck wants The Chinese Room to apply its arthouse background to traditional genres moving forward, bringing an “obsession with story, world-building and atmosphere,” he says. Orpheus fits the mold: It’s a traditional 2.5D action-adventure mobile platformer on the surface, but its world is filled with Soviet space technology, Russian mythology, and ancient creatures, including a giant dinosaur and a mysterious tentacled beast. “Orpheus‘ story is so epic and ridiculous and, hopefully, it’s funny. It’s a romp. It’s a real homage to Ray Harryhausen movies, ’30s serials like Flash Gordon and stuff like that.”

The move to mobile development is by no means permanent, but Orpheus is the perfect practice for building bigger games, Pinchbeck says. “It’s going, ‘How do we fit this huge thing onto this small thing? How do we absolutely make sure we have the highlights only, and everything is polished to the absolute nines?’ And going back to console or PC we’ll hopefully already have those good habits, so it’s not just infinite splurge.”

As for the future, Pinchbeck has plenty of ideas lined up. One of those is based on the novel he’s written, and I get the impression it’s the one he’s pitching hardest. “I wish I had time to write a novel for every game I was working on. I spent 18 months working on the mythos and the characters—they’re just solid.” He also mentions how much he loved the fact that the 1984 space trading adventure game Elite came with a copy of The Dark Wheel by novelist Robert Holdstock—I wouldn’t be surprised if this game does the same.

He won’t reveal any details of the story or setting, but I spy some artwork on the walls of The Chinese Room’s offices linked to the project: an ice world with jagged buildings reaching skywards, a space station suspended above the earth, a sprawling treehouse town in a jungle canopy. I like how unpolished it looks, how lived-in every image seems.

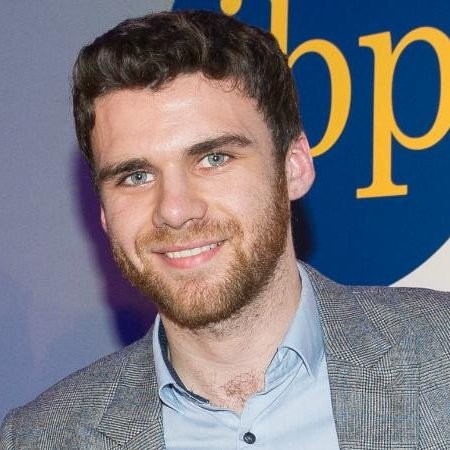

Credit: Jim Holden for EGM

After Orpheus, The Chinese Room will have two games in development simultaneously, Pinchbeck says. One of them might be The 13th Interior, which he first mentioned to Eurogamer back in 2017. The idea started as a board game, morphed into an isometric RPG, and then took on elements of survival horror. “It’s just a story I really love, it’s completely barking mad. It’s very left field, very out there, but in a way that the time’s good for it at the moment.”

He also talks about his love for first-person shooters. “At the moment I’m plowing through Borderlands 3 which I’m absolutely loving. Give me Borderlands, give me Metro Exodus, that’s the stuff which I really love. I don’t know if that means we’re necessarily ever going to make an FPS, but what I’m enjoying is being in a place where I’m working with really good designers from across genres.”

But Pinchbeck has no desire to work on walking simulators again. Some studios who make a splash in one genre find it hard to branch out. The Chinese Room now has a chance to branch out. “It’s a really good place for us to be coming out and going, ‘We’re not just the studio that makes walking simulators. We’re a studio that makes great story games.’ I want it to be so if we make an FPS, you play it and you go, ‘That’s a FPS that only The Chinese Room could make.’”

Pinchbeck compares it to the feeling you get when you play a game from Dishonored developer Arkane, one of the studios he’s aspiring to emulate alongside Naughty Dog and Ninja Theory. “Those great studios where they’ve got such an indelible DNA, it almost doesn’t matter what they do—you know it’s them… Those studios where people talk about storytelling in games, I want us to be mentioned in the same sentence.

“Name-checking those studios is not a statement of how good you are. I think that’s where you should be going. You should say: ‘We want to be one of the best in the world.’ Why not?”

Header image and all uncredited images: Jim Holden for EGM

Samuel is a freelance journalist. When he first played TF2, he couldn’t work out how to fire his gun—until he read a troubleshooting guide. You can find him on Twitter @SamuelHorti.