This article discusses plot points and events from the entirety of Death Stranding’s story.

“I brought you a metaphor,” a character says toward the end of Death Stranding. She hands protagonist Sam Porter Bridges (Norman Reedus) a mask that she believes will help one of the world’s violent post-apocalyptic factions snap out of their delusions and begin cooperating with others outside of their immediate community. As goofily direct as this line is, it’s emblematic of how the game communicates its most vital ideas, offering the audience symbols drawn from our own lives in the hopes that we, like the group being shown the mask, will be inspired enough by metaphor to work toward a better way of life

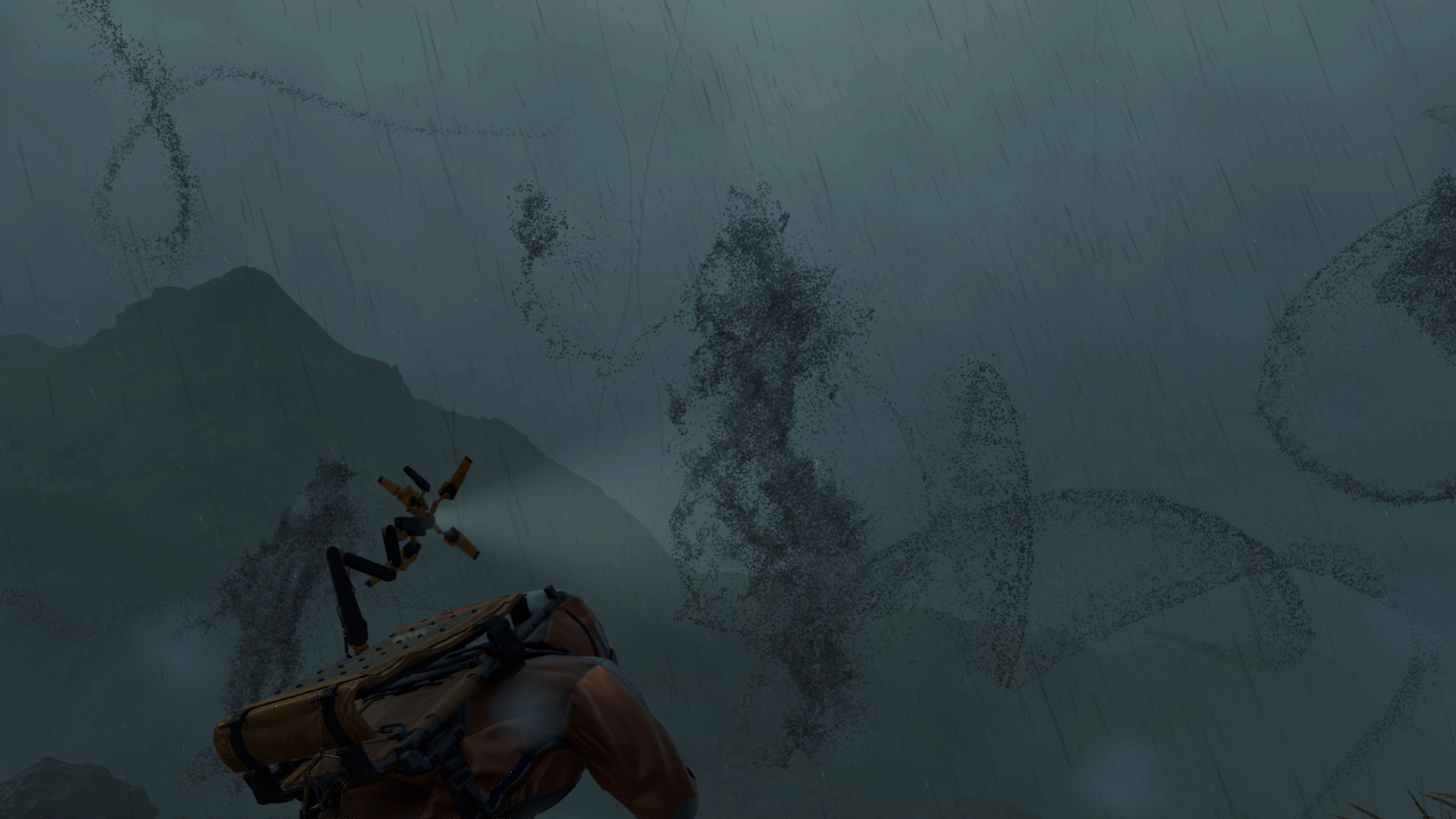

At the center of its allegory, there’s a baby in a jar. “BB,” as it’s called, is a newborn connected to both the worlds of the living and the dead—a “Bridge Baby” per the game’s flood of fantastic terminology. Sam carries BB with him as he travels westward across the United States, relying on his little pal to help him sense when the inky silhouettes of ghosts lurk around him, waiting to drag him into puddles of glistening black tar and down to an otherworldly stretch of coastline. Occasionally, BB will cry from the sound of gunshots or when jostled around as Sam slips down a hill or trips over a rock. At these moments, Sam can hold BB’s jar out in front of him and soothe his companion by gently rocking the container back and forth until the child’s calmed and ready to serve again.

All of this might make it sound like BB is a simple tool—another piece of equipment akin to the ladders, ropes, and various weapons Sam uses to traverse Death Stranding’s moldering American landscape and overcome its manifold dangers. But that idea is quickly complicated. In a game so densely packed with metaphor, BB, insulated in the amniotic fluid that fills its container, stands in for the new world that might be born from the apocalypse. As such, the baby is considered by some characters to be disposable, and by others to be the locus of the most intense personal emotions possible. The child’s mysterious past makes BB a marker of all that’s come before, and a symbol of a horrifying history that’s somehow led to a society okay with keeping babies encased in jars. Considering that this is a baby, which will grow up to form the next generation, however, mean that BB inherently symbolizes the future above all else. The child represents what comes next not just for the game’s characters and plot, but those who play Death Stranding, too.

Sam’s goal in Death Stranding is simple enough on its surface: Tasked by the recently deceased American President to rebuild the nation’s communications systems and track down a woman named Amelie who’s being held on the continent’s west coast, he travels across the country, reconnecting isolated pockets of society by convincing them (mostly by lugging important cargo from place to place) to hook up to the internet-like “chiral network.” If fully established, this network will reestablish communications, joining the fragmented country together again. Sam’s lonely journey is a deliberate evocation of two formative periods in American history. Through his gruelling trek toward the Pacific, Death Stranding calls to mind the 19th century westward expansion, which solidified the nation’s sense of identity through a now-mythologized display of brutal individualism in the hopes of material gain. Chugging branded Monster Energy drinks and laying down continent-wide infrastructure, Sam’s journey also references the postwar period where the United States emerged from the Second World War as a superpower, commanding vast overseas holdings and further codifying a patriotic spirit based on consumer comfort and military victory.

Sam brings his clients containers filled with medicine and equipment, trudging across rocky plains or struggling through river currents, climbing across snowy mountains and over slippery, moss-covered hills. Along the way, he sneaks past or fights off scattered groups of cargo-obsessed rogue porters, all the while leaving behind trails of glowing footprints that other migrants can use as a guide west. It’s easy to see him as a romanticized cowboy in all of this. Sam ranges across this dangerous terrain with his aching back or floating cargo flat piled high with goods, murmuring to his only living companion (the baby in a jar replacing the faithful horse) as he forges a trail from the government-controlled east to the “untamed” west. References to this era are coupled with the evocation of the postwar period, when vast armies of laborers under President Eisenhower’s Federal Highway Act further networked the country through the construction of interstate highways, cementing previously disparate states and territories into a more unified whole. Echoing these workers, Sam brings building materials with him as he goes, laying down foundations for high-tech service stations, crude trails made of climbing ropes and steel ladders, or, most notably, new paved roads and sturdy bridges.

In its use of 19th and 20th century imagery, Death Stranding consciously evokes the violence that hangs over both eras, be it America’s use of the nuclear bomb at the end of World War II or the systemic brutality that accompanied the country’s western expansion. Most strikingly, the game is filled with constant reminders that everything players see and do in its setting takes place in the shadow of a horrific tragedy—the “Death Stranding” that left regions of the country marked by enormous craters caused by bomb-like “voidouts” and the ordering influence of a recognized government in shambles. Its main characters are all touched by the instability of their country and this recent terror. All of them have been marked, physically and mentally, by the cataclysm that partially destroyed their country—and each of them has thoughts on how America can move on from the chaos.

The look of the game’s world reinforces this sense of a country on the precipice of great change. Despite taking place in the United States, Death Stranding’s landscape more closely resembles the dark earth and dramatic slopes that fill islands like Iceland, Hawaii, or Ireland than it does American geography. Sam’s trek sees him moving across a landscape that seems perpetually overcast, the sky unsure whether to break out in torrents of deadly rain or allow for a few moments of sunshine. Any ground not covered by bright green moss or thick drifts of snow is made up of black, volcanic soil—so impossibly dark and rich that the earth itself seems ready to either grow fresh, abundant life or erupt again into a new process of explosive destruction and human-free renewal.

For most of the game, it seems equally likely that either possibility—death or rebirth—will win out in the end.

The games created by Hideo Kojima, Death Stranding’s director and co-writer, have always struggled with trying to identify the best way to live in the postwar, postmodern era. The bulk of his work consists of the Metal Gear Solid series, whose paranoia-soaked military stories are obsessed with nuclear annihilation, the failures of dominant political ideologies, and whether it’s possible to forge a good life within the confusion of constant warfare and the psychic alienation of the digital age. The struggle that animates those games continues in Death Stranding. Right from the game’s opening, players hear Sam describe a pair of world-changing explosions—one, the in-game Death Stranding, is on par with the Big Bang—whose aftermath humanity must now figure out how to navigate. Failing to properly reform society will lead to a final explosion that humanity will be unable to survive.

Kojima evokes the foundation of America in many aspects of Death Stranding’s narrative, but most pointed is its decision to tie together a story of postwar nation-building with the immediate and lingering psychological horror of the United States’ use of the atomic bomb in Japan. The game’s characters literally live with the ghosts of the past all around them—the floating “Beached Things” or “BTs” that Sam, with BB’s help, must avoid or defeat throughout his journey. The landscape of America is covered with these hungry revenants, mindlessly grasping at the limbs of those who, unlike them, have temporarily escaped death’s clutches.

As in reality, life in the aftermath of the atomic bomb forces questions of where, exactly, we’re going as a species. Sam’s opening words imply that failing to answer this is existentially profound—and not just in a philosophical sense. Death Stranding, especially in its final hours, wants us, as players, to consider that we can’t simply continue sleepwalking toward the ultimate destruction of self-inflicted or natural extinction.

Its warning manifests most starkly through a trio of chapters that see Sam transported into a hellish reality where 20th century wars rage in a never-ending loop. Each of these sequences stars Mads Mikkelsen’s Clifford Unger, the ghost of a U.S. Special Forces soldier who stalks the muddy trenches of an infernal First World War battlefield, the streets of a bombed out Eastern European city during WWII, and a humid river delta from the Vietnam War. Yelling for the baby who was taken from him before his death, the undead Clifford commands troops of skeleton soldiers to attack Sam and steal BB away from him.

These scenes are further complicated through late-game twists, but even at first glance, it’s clear that Death Stranding depicts the previous century’s wars as a dire warning of where we come from and where, if Clifford can abduct the symbolic future of BB into his personal hell, we’re returning to as a people. Global violence, from the World Wars to one flashpoint of the international Cold War, is rendered in these as senseless and terrifying. The ghosts and skeletons that Sam either slips past or shoots will fight forever, like deadly reenactors. There are no larger politics or small stories of strategic movements or individual heroism portrayed here. Instead, soldiers simply die over and over, screams echo from the distance, and fires burn amidst the destruction of collapsing buildings and the brutalized natural world. War is, literally for Sam, Clifford, and the player, a never-ending hell filled with nonsensical torment. It’s also shown as the end point for a humanity that can’t figure out how to do better.

In highlighting the 20th century’s wars as the trauma of our collective past, Death Stranding again connects seemingly distant history with the modern day. Not only is Clifford decked out, regardless of the war scene’s given historical era, in modern military fatigues and equipment, but the straightforward, mindless violence of his scenes is coupled with the threat represented by the inclusion of in-game terrorists whose destabilizing, cataclysmic presence mirrors the real-life present day.

Death Stranding’s world is plagued by seemingly purposeless terror attacks carried out by a group called the Homo Demens that’s led by a monomaniacal figure named Higgs. The player encounters him through flashbacks and surprise run-ins that see Higgs trying, or succeeding in, setting off miniature nuclear bombs that level America’s already-struggling cities. Later, when Sam finally confronts him, we learn that Higgs’ goal is, in short, to harness every American’s unique, purgatorial “Beach” (each made up of individual pockets of a kind of deathly collective unconscious) and bring them together to trigger a mass extinction event. The exact mechanisms that explain how this works are described through torrents of fictional backstory, but the meaning of his terror attacks is simple: Higgs wants to use Sam’s work to reconnect the country not as a catalyst for a hopeful defiance against the end of the world but as a populist movement with purely destructive aims.

This, initially, seems to be how Death Stranding will subvert the dozens of hours of optimism that defined it before Higgs’ plan is revealed. Human connection—Sam bringing people together again by traveling the country, joining them in a common cause—seemed like the game’s only response to the historical misery its fiction evokes. Higgs turns the idea that a united collective is always positive on its head. Here, rather than simply push back against the kind of self-interest that’s led to the isolationism of Brexit and walls along the American-Mexican border, Kojima suggests that people banding together can be part of the problem in the first place. Populations united in service of a common purpose can defeat isolationism of the kind Death Stranding rails against, sure, but, guided by nativist sentiment (as has happened in America, Britain, Hungary, Poland, France, or Brazil) it can also be a rallying force for mass action that lashes out at the world in reflexive violence. Remembering Clifford’s World War scenes and the ghosts of soldiers doomed to fight never-ending battles, the specter of the Axis powers—fascism as the height of twisted, populist violence—or the bloated war machines of 1910s and Cold War empires destroying millions of lives, begin to loom over the game like a shadow as massive and blood-chilling as the skyscraper-sized BT that Higgs summons while explaining his revelatory, villainous mission statement.

At this point, Death Stranding seems to be purely nihilistic. Even if Higgs is defeated, the worldview that created him will go on. The optimism of Sam’s goal suddenly seems hopelessly naïve. During these scenes, Higgs tells Sam that he can speed up or slow down his world-devastating plans, but he can never stop them because, ultimately, death on a global scale is the only way humanity is headed on a long enough timeline. Selfishness, even within bonded communities, will continue the wars and environmental destruction that’s brought us to the precipice. Higgs, absorbed into the towering void of an enormous BT’s chest, says this in the voice of all those who have given into the sense of inevitability that the dread-soaked era of a pre-apocalypse engenders. He represents giving in—embracing the void.

Fortunately, the game doesn’t let Higgs have the last say.

Death Stranding recognizes how valid dread and hopelessness, and resignation are in the face of such overwhelming terror. Rather than end by merely affirming this kind of intellectual and emotional despondency, though, it urges players to rally onward and work for a better tomorrow. Its narrative is filled with nightmarish signs of despair. The title, coupled with imagery from its representation of the world of the dead, references the phenomenon of mass whale beachings (“cetacean strandings”), suggesting that communal mammals, not entirely unlike us, are prone to self-annihilation. Its historical and modern metaphors draw on the atomic bomb, the rise of the far right, the lies of nationalism, the inevitability of global terror, and the inexorable collapse of our planetary ecosystem. Most frightening of all, Death Stranding imagines a future where all of these real-world problems are bound to continue regardless of our best efforts to band together in defiance of them.

And yet, by the end of the game, players aren’t meant to feel hopeless, but optimistic. Partially, this comes from the story’s insistence that, despite modern politics’ perversion of collective action, this same tendency to come together can, if we channel it properly, save us. Throughout most of the game, Death Stranding encourages acts of basic altruism. Its online systems allow Sam to leave helpful items behind for other players; jamming on the controller’s touch pad gives strangers experience points; using important supplies to build navigational tools like ziplines or bridges is encouraged not by any significant, tangible reward, but because another person might have an easier time crossing a mountain or river because of it.

Unmotivated, small-scale empathy is shown to be the only unquestioned good. Rather than trust in the leadership of individuals, some of whom represent destructive political ideologies or philosophical goals, the only path forward is a morality guided by unselfish kindness. Today’s politics make us lose sight of these sorts of essential truths—the kind that hold even when everything else has to be tempered with confusing, morally flexible realpolitik. Taking place within a world filled with existential horror where nobody (especially not a president named Samantha America Strand) can be wholly relied upon, Death Stranding says that making connection the foundation of everything we do is the only realistic path through the fear, uncertainty, and confusion that defines the present and its own vision of the future.

Most crucial among everything the game communicates, though, is BB. Intergenerational failure, a constant theme in the Metal Gear Solid series, is of the greatest importance to Death Stranding, and nowhere is it clearer than in the figure of a tiny baby kept in a jar. Throughout the game, BB is fought over by everyone from Clifford, the soldier who’s tormented by visions of past wars, to callous scientists seeking to use the next generation as fodder for their own unimaginative, short-sighted goals for humanity’s future. Despite their best efforts, Sam manages to keep BB close while he struggles with the apocalypse he lives in and against the one he knows will come if he can’t figure out a way to avert it. He, the precursor for the same technology that created BB, grows from an alienated member of society with no serious interest in the child to someone who loves the baby and all it symbolizes. In the game’s final moments, even knowing that doing so comes with a high chance that the baby will suffer more than ever because of his choice, Sam removes it from the shelter of a jar that can no longer keep it safe, bringing it fully into the world. Exposed to its surroundings, BB seems to be dead, after all. It’s the kind of tragedy we’d expect would happen. But, after a desperate few moments, the child returns to life. It’s ready to shape what will come next and, through the simple facts of its continued existence and the empathy that’s brought it into the world, grow toward a better future, imperfect as it might be.

All images credited to Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Reid McCarter is a writer and editor based in Toronto. His work has appeared at The AV Club, GQ, Kill Screen, Playboy, The Washington Post, Paste, and VICE. He co-wrote and co-edited the books SHOOTER and Okay, Hero, edits and contributes to Bullet Points Monthly, and tweets @reidmccarter.