Alex Hutchinson’s final few months at Ubisoft Montreal were the worst of his career.

After spearheading development of both Assassin’s Creed III and Far Cry 4 as creative director, he’d finally had a chance to build an original concept, a non-violent, “toy-like” sci-fi game codenamed Pioneer. But it quickly collapsed. That was partly down to the team’s over-ambition, and partly because Ubisoft failed to offer the support the project deserved, he tells me. “Every day was uncomfortable.… You’re just in this grind, and that drives you insane. It was the first time in almost 20 years that, when we stopped, when we let it go, I think I was pretty burnt out.”

Things got so bad that Hutchinson left the developer in 2017 to start Typhoon Studios, and its debut project, a first-person adventure game called Journey to the Savage Planet, is due in 2020. After meeting at his new base near Jean-Talon Market we walk to a bar on Boulevard St. Laurent, the very street that Ubisoft Montreal’s office looms over. Inside, he speaks candidly for the first time about his departure, about the freedom he’d been given during his seven years at the company, about why he can’t get over Assassin’s Creed III’s failings, and about—during his last few months at the studio—his growing frustration at Ubisoft executives.

We also speak at length about his quick ascendancy from junior developer to creative director, how he showed up at his first triple-A job only to learn the game had been canceled, why giving players more power is “the worst thing” to happen to gaming in the past 20 years, and how he ended up in a recording studio listening to will.i.am beatboxing in a nonsense language.

Hutchinson’s dream of making games felt out of reach when he graduated from Melbourne University with a Masters in English and Writing, he says. He couldn’t code, couldn’t draw, and nobody was hiring designers. Producers existed, but “in those days they just bought the pizza,” he says. After a handful of unsuccessful job interviews—including one where he was told, “We think you’re very creative, but you’ll quit”—he landed a gig at Torus Games, which specialized in licensed games for handheld consoles. His first project was a Minority Report tie-in for the Game Boy Advance. It was a “classic bad idea.”

“We tried to make this weird integrated cover system where you double-tapped the D-pad and you’d roll into cover and snap to it,” he says. “It was stop-and-pop combat in an enforced 2D, fake 3D perspective. It was way over-ambitious. By the [end] we realized it wasn’t much fun, but we didn’t have enough time to fix it.”

Despite not making anything special, Torus was an “awesome learning experience” that prepared him well for working at bigger studios. He had to build games quickly “from start to finish… doing everything from having an idea to seeing it work, to fixing it, to reading critiques, and then getting through the publishers.” During that time, he met longtime friend Reid Schneider, now his business partner, on a “PS2 pitch that didn’t go anywhere.” Schneider got a job at EA and passed Hutchinson’s CV around the company. “You need to get out [of Australia],” was Schneider’s advice.

Eventually, Hutchison did just that. In October 2003 he boarded a plane to California, where he’d touch down as a designer on a triple-A project at Maxis, part of EA. Or so he thought.

“They canceled the game while I was in the plane,” he says. “My first meeting at Maxis was them asking, ‘Are you sure you want to stay?’ I’d sold all my possessions and gave up my lease. I said, ‘It’s very nice of you to ask, but I don’t have anywhere else to go.’”

The game in question was a console version of SimCity, the classic PC city-builder. Hutchinson’s vision was, just like with Minority Report, “wildly ambitious.” You’d play from a top-down view, but at a button press you’d “switch to a third-person, Grand Theft Auto–style view,” completing auto-generated missions based on the city you’d created. “Missions would emerge from the kind of buildings that would come up. If you made a slum city, you’d have crime-stopping missions, or you could just zoom down to the street level to tour your city. I thought it was a pretty neat idea.”

After Maxis canned the project (Hutchinson says the execs “always struggled to fall in love with their games on consoles despite strong sales”) he moved onto a Sims PSP game. “If Sims was a parody of suburban life, what if we made a parody of urban life? The first idea I had was that instead of building houses, you’d build small businesses. You’d inherit a failing fish-and-chip shop, you could replace the equipment and customers would arrive, the same way people visit you in The Sims. You could fix it up, and it’d be a parody of gentrification.”

Unfortunately, Maxis found out Sony was pushing back the PSP by two years, and Hutchinson’s game ground to a halt. One year in, he’d had two projects canceled. Hardly an ideal start to his triple-A career—but he was simply happy to be out of Australia and making games for a living, he says. “I was single. I was getting paid real money. I was sleeping on a mattress, but I was sleeping on a mattress in downtown San Francisco, going out and seeing what life was about. I was loving it.”

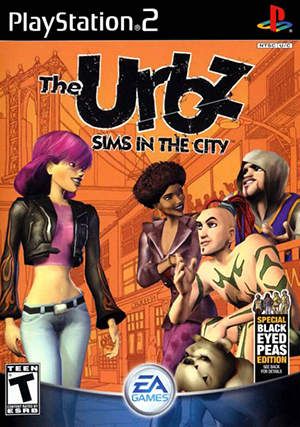

Credit: EA

After another reshuffle, Hutchinson became co-lead designer for the final few months of The Urbz: Sims in the City, which incorporated a few ideas from his aborted PSP game. The thing he remembers best is the soundtrack. “We’d hired The Black Eyed Peas to do the music. They’d signed a contract—I don’t know if they’d read it—to do a bunch of original tracks for us. And then they played the Democratic National Convention and blew up, and they were like… ‘fucked if we’re doing this.’”

In the film industry, the group would’ve been sued, Hutchinson says. “But in video games it was, ‘they’re a different medium, they’re cool,’ so we just groveled.” Instead of original music, Maxis got will.i.am beatboxing Simlish versions of his lyrics over Black Eyed Peas tracks. While The Urbz had its moments—and left a “weird, iconic” legacy—Hutchinson says “it’s the only game I’ll drop off my CV if pushed.”

Despite only having a couple of canceled projects and a mediocre game under his belt at Maxis, Hutchinson had quickly built a reputation within EA. Nobody had yet figured out how to teach or analyze game design, so it was “a bit of a Wild West,” and purely “results focused.” He got results. “I kept putting out fires for them, so they kept promoting me,” he says, and his reward was a solo lead designer role on the console version of The Sims 2.

It wasn’t just Maxis that were impressed. Blizzard came calling, offering him the lead designer role on Diablo III, a job he’s glad he turned down because the game didn’t release until several years later, in 2012. Instead, he opted to stay at EA to tackle Spore, the genre-spanning god game that never lived up to its promises. “That was a three-year process assessing what was there. They had this huge promise, and everyone was really excited, but nothing was real. The game was just a bunch of ideas.”

It was Hutchison’s first taste of inflated fan expectations. Maxis “let it get out of hand” by serving up vague guarantees of freedom that it could never deliver on. Players were hyped up, but didn’t know what the game was really about. “When players told me they were excited, I’d ask them, ‘Why? What do you think the game is?’ And they’d stall. Then I knew we were in a really dangerous spot.”

He likens it to No Man’s Sky, another game that oversold itself. “There’s magic in that game, but it’s overshadowed by the hype and fantasy of players. I’ve never met [No Man’s Sky creator] Sean Murray”—who was born in Ireland but spent some of his formative years in Australia—“but for a while I toyed with the idea of sending him an email saying, ‘From one Australian to another, this is going to suck.’”

Credit: EA

To this day, he still finds fan pressure terrifying, he says. “When the expectations are large in games—I had that a couple of times with Assassin’s Creed III and Spore—you realize you can’t win… even if you make a great game.”

But he’s gotten better at handling it, and recognizes that overpromising can open the door to criticism. “You can say all kinds of things that will get you hype but maybe stretch the truth about what you’re able to achieve. I just try to say what it is. With Spore, it was too late. With Journey to the Savage Planet, we don’t want super-hyped previews. It’s really dangerous. We just want people to say, ‘That looks interesting, I’ll give it a shot.’”

The final stages of Spore marked a “crazy six months” for Hutchinson, in which he’d spend alternate weeks in California finishing development and in Montreal kicking off Army of Two: The 40th Day, his next project. As creative director, it was the first time he’d made a game he would personally buy on release day, he says. “Before that, my job was essentially to be the best designer for Will [Wright]’s ideas, and I wanted to get back to something that was more my taste: a controller-based action game with skill mechanics. It felt much more comfortable.

“I fell in love with The Sims, but early on I had to imagine what another type of player would do with that game, to put myself in their shoes. Whereas with Army of Two, Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry and Savage Planet, they’re much more games I’d pick up on day one and play. It was more natural to have ideas and get excited about them.”

Army of Two also sparked Hutchinson’s love of what he calls “intimate [two-player] co-op”, which later made an appearance in Far Cry 4. Blasting through the shooter was “almost like going on a date. You play with your husband or your kid or best friend, and you’ll talk the whole time. I thought there was something intimate and fabulous about it.”

“Ubisoft is not a monolithic object—each team is different. The team knows exactly how they’re being political. They’re just not allowed to say anything by corporate.”

Hutchinson didn’t see a future at EA beyond Army of Two and, when development ceased, felt the time was right to push for a job at Ubisoft. He’d spoken to the company for years about potential roles, but the timing had never worked out. “Then one day I ring up and say, ‘I’m just finishing a project, I don’t see where the studio is going after this one, you guys have the biggest studio in the world.… What’s going on?’ And amazingly they wanted me to be game director on Assassin’s Creed III, which I thought was super complimentary.”

Within three months of joining, creative director Patrice Désilets left, and Hutchinson stepped into his shoes. It was a new level of pressure and expectation. “It’s a bit like the sun: You try not to look at it.” He ignored fan chatter, and just focused on the next small goal. “I’m an anglophone in a very francophone team who’s now got the top job, so day-to-day you’re trying to convince these guys, ‘Don’t worry about the reception in the outside world, just try to get the team unified behind an idea they believe in.’ You do it piece by piece, week by week, month by month. I escaped the terror of it by not having time to stop and think about it.”

The team was “so close to doing what we pictured” with Assassin’s Creed III, he says. The developers ticked every item on their wishlist, such as naval battles, free-running in trees, wilderness environments, and a “fake start” where you play as your father, who turns out to be a Templar. “The things that fucked us were pacing and tuning out bugs,” he says. “I think the naval combat was great, and we delivered on the free-running, but the story was too dense, and the intro was too long. If we’d had six more months to edit it, we could’ve fixed it.

Credit: Ubisoft

“It’s funny to say it was terrible in a game that averaged 82, 83 on Metacritic and sold 40 million copies, but at the time we had such crazy expectations that it was pretty depressing.” The reactions of fans and some critics played into that; negative comments and reviews ”polluted the team’s perception of the whole project.” Retrospective takes—including this recent one from Kotaku—have been kinder, which has helped Hutchinson realize that most people who played Assassin’s Creed III enjoyed it. But even now, he finds it hard to let it go. “You can’t escape it, you just have to make peace with it. We’re human, and we tend to fixate on the negatives.”

Dealing with fan criticism is something Hutchinson has found challenging throughout his career, he admits. “You’re a much hardier soul than I am if you can let it wash over you. In the moment, it’s like somebody calling your kid ugly.” It’s especially difficult when you’re a project lead and the team looks to you, he says. “[The Assassin’s Creed III team] were all hyped up, and you can feel them reading something negative and then sort of looking over. It all tends to funnel into the director and producer.”

His reaction to negative opinions from reviewers or fans is similar to the stages of grief, he says. “You argue about it in front of a team, and then you’re miserable about it, and then you realize, you know what, it’s not all the coverage. We’re focusing on these two articles, but these ones are lovely. And then you accept it and move on.”

In the end, simply going into work was like a “Greek torture,” Hutchinson says. “You’re pushing the boulder up the hill, and every time you think you’ve got it, it just rolls back down.”

Sometimes, fan criticism is valid, but it often steps over the line, and Hutchinson knows developers that have received death threats just for tuning weapon balance. It’s part of a trend of growing fan entitlement that has emerged over the last two decades, and it’s the worst thing Hutchinson has seen since he’s been in the industry, he says. He points to the era around Spore, where studios were keen on “engaging the community in development,” as the “start of the evil.”

“I think the Chinese wall between developers and their audience was a secretly awesome thing, and now there’s a sense of entitlement with the audience, a closeness of contact that even other media doesn’t do the way we do.

“It’s killing creatives, I think. You’ve seen them leave the industry. The founders of Bioware left because they got shouted at for the end of Mass Effect 3. You’ve killed the people who made the games you love. It’s fucking moronic,” he says, the most animated I’ve seen him during our conversation. “People leave all the time, old-guard people who have done well but have lots more to give. There are lots of great games that we’ll never get to play because a thousand 14-year-olds threatened their family. We get no value out of it.”

It’s hard to ignore those threats and insults, and they inevitably darken your mood, sometimes changing the way you behave at home with your loved ones, he says. “You can’t not look, and then it affects you, and you’re like, ‘For fuck’s sake, I don’t even know who this person is and now they’ve made me feel bad.’ You can have 100 people say your game is great, and two people say, ‘I hope you die,’ and you go home and those are the only ones you tell your girlfriend about.

“Or worse, you don’t say anything, and now you’re in a shit mood.… It’s gross.” That toxicity has “always existed, but now they have an avenue to tell you about it. [Before] the creators weren’t sitting in it, and fans didn’t have the ability to send it to your house.”

Hutchinson has felt it firsthand: He’s had a stalker for the past six years, he tells me. This individual has sent long emails to his colleagues pretending to be his wife, created social media accounts with his last name and photoshopped his children into their photos, and once sent 30 boxes of stuffed animals—one a day for a month—to the Ubisoft Montreal office. “Some of the people you work with think it’s funny. And you’re like, yeah, it’s funny, until they turn up at your door. Or turn up at [my child’s] school.”

Having kids helps you deal with the vitriol, he says. “When you have a couple of kids, the ability of the internet to wound you goes away, which is an immense relief.… The kid gives me a hug, it’s really nice, and you know there will be something on TV when you get home. You don’t feel like you’ve failed in life.”

Hutchinson’s solution is simply to “go forward, to keeping making games.” For Hutchinson, that meant moving from Assassin’s Creed III onto Far Cry 4, albeit with a brief hiatus. “The core Assassin’s Creed III team were given a moment to try to build a new IP from scratch, which we’re not legally allowed to talk about. It was a space game, we were trying to innovate on types of movement, try to make a non-violent game. It was incredibly ambitious, and we just couldn’t get it tight enough to get through the last hurdles.”

Remember that, because we’ll return to it shortly.

Far Cry 4 is the game Hutchinson has least regrets about, he tells me. “I was really pleased with it.… There’s nothing big that bothers me about that game.” He liked the setting, the two-player co-op, and the “false-bottom” opening, which meant you could technically finish it within minutes of starting. He also enjoyed the humor—a testament to the way designers can “put their stamp” on games at Ubisoft. Developers at the studio have plenty of flexibility, even when they’re working with an established franchise, he says.

Credit: Ubisoft

“Far Cry has to be an open-world shooter with animals. Whatever else you want, go nuts. I always thought [these games] felt like new IPs, which is great. You have the safety and budget of a franchise, but really you can do what you want. A new character, new story, new setting, new systems, with an engine that works—you’re like, ‘This is pretty fucking fantastic.’”

The humor was a way of making some of the game’s heavy themes—the setting is a civil war between a rebel movement and an army controlled by a tyrannical king—more accessible, Hutchinson says. The next game in the series, Far Cry 5, was even more political, and Ubisoft has attracted criticism for insisting its games don’t make political statements.

“Everyone needs to understand that the teams are knowingly being political, and the company is knowingly trying to pretend they’re not,” Hutchinson says. “Ubisoft is not a monolithic object—each team is different. The team knows exactly how they’re being political. They’re just not allowed to say anything by corporate.”

The end of Far Cry 4 was the beginning of Hutchinson’s departure from Ubisoft. The company returned to the Assassin’s Creed III team’s sci-fi idea—codename Pioneer—and put Hutchinson at the helm. But it didn’t unfold as planned. They wanted to be original, to experiment, but it resulted in lots of “individually brilliant ideas that we couldn’t get to gel.”

The team wanted to create a “toy-like, experiential kind of game” set in space but struggled to produce anything concrete. In the early development of most games, studios reach a point where they can demonstrate that “there’s something here,” even if a lot of it “looks terrible.” It usually involves a rough playable build. “It’s amorphous and intangible and emotional, but franchises usually start from that point.… [For this new IP,] we were too ambitious, and so we never made it concrete enough to get over that line,” Hutchinson says.

Part of the fault lies with Ubisoft executives, he argues. He felt the team had just about got to a point where it could demonstrate the game’s potential, but corporate disagreed. “We felt like we needed them to help us move forward, and they felt like we had to prove it was worth moving forward. We got stuck in this circle that we couldn’t get out of.”

Hutchinson was frustrated: He believed the way to break the impasse was simply to go ahead and make the game. Pioneer didn’t have a defining mechanic that you could prototype to instantly prove its worth—it needed its component parts to work together. “Firewatch without Olly Moss’s art as modelled by Jane Ng would suck, but in that world it’s beautiful and immersive. [With] some things, you need the realization. I felt like the game we could make… needed to be finished, and we needed support to finish it.”

Credit: Ubisoft

He says there was no real animosity between himself and executives, but “there was definitely a conflict of goals. Ubisoft has a kind of scale and type of game that they want to make, which is very successful, and our team wanted to try something different, which didn’t really mesh with their internal goals in Montreal, and we weren’t getting strong enough results fast enough for them. I think Ubisoft sees gameplay in a very specific way, and we were drifting toward a more toy-like or experiential kind of game which they never really got behind, I don’t think.”

When executives are unsure of a project, as they were for Pioneer, it rubs off on developers, and they start to spin out of control, Hutchinson says. “And then corporate will say: ‘You’re spinning!’ And then the team can’t stop, and then the project is ruined, or at least the team has to be moved on. And in my opinion, you made them spin because you didn’t let them move forward.”

Developers in that situation make bad decisions—or sometimes, fail to make any decisions at all, which can prove fatal for a new property. “On a franchise, you can say: ‘We’re keeping the gunplay. You designers make a list of all the ways to improve it.’ And then we make a list of three big risks in the hope that two come good. With a new IP, when you say gunplay, someone will say: ‘Do we need guns?’ And then someone will say they don’t like guns, someone else will say they don’t want to play a game without guns.

“At a point you have to say, ‘There’s a fucking gun in it. Here’s your gun.’”

The team’s non-violent approach was also part of the problem, he explains. “It was meant to be experiential, and we had lots of ideas about physics in space. The big problem is when you take out the violence, you realize you’ve taken out a lot. I don’t know any mega franchises that don’t have killing, except sports games. It’s really hard, and we just couldn’t find it.”

In the end, simply going into work was like a “Greek torture,” Hutchinson says. “You’re pushing the boulder up the hill, and every time you think you’ve got it, it just rolls back down. But, you know what, we’ve pushed boulders up the hill before, so get behind the boulder. You’re in this grind, and that just drives you insane. That was the first time in almost 20 years that when we stopped, when we let it go, I think I was pretty burnt out.”

They never worked long hours on Pioneer, but “every day was uncomfortable”—Hutchison likens it to staring at a math equation on a chalkboard every day, for nine hours, and being unable to solve it. Eventually, it got to be too much for him. He’d long-harbored thoughts about starting his own game studio, and had even joked about the idea a decade earlier with Reid Schneider. His frustration with Pioneer pushed him over the edge.

“It’s fun to play with other people’s time, but at some point you think, ‘Is this all there is?’ You can put your own spin on it, embed your ideas in it, but it’s not yours and will never be yours. And if you’re obnoxious enough to think that you’d like it to be yours,” he chuckles, “then you only have one option, which is to do it yourself.”

When it was clear that Ubisoft’s goals were at odds with the Pioneer team, the studio moved Hutchinson, the producer, and the game director off the game. “Sitting in the corner is no way to live, even if it would have eventually lead to a new project…. The moment Ubisoft made it clear they weren’t going to proceed in the way I wanted to with that game, then we had the serious discussions [about a new studio]. What would it look like? Who would jump ship with us? You’re making a list of people, putting a percentage chance on each person.”

To Hutchinson’s surprise, almost everyone he approached was willing to climb aboard. Developers were getting tired at Ubisoft, having worked on three or four big franchise games in a row—they’d “done their dash” and wanted a new challenge. “At that point, what are you trying to prove?”

Many of them thought that if Hutchinson’s venture imploded, they could always move back—a sentiment he agrees with. “If it blows up, then great, we tried, and we’d probably be much better employees, because we wouldn’t be sitting there thinking, ’If we were running the company…’”

It was only after starting Typhoon and securing funding from Chinese investment group Makers Fund that Hutchinson realized just how much his final months at Ubisoft had taken out of him. He felt mentally foggy and didn’t fully recover for a year. In retrospect, he probably should’ve taken time off, he says. “You only notice when it starts to lift. It’s like lack of sleep. You wake up and think, ‘I feel way better today.’ And then that idea you have is great, and you feel yourself getting back to normal. But it took a year, and it was weird, I didn’t like it. So one of our rules at Typhoon is: no crunch.”

When reached for comment on Hutchinson’s characterization of Pioneer and his departure, Ubisoft acknowledged the request but did not respond further before publication.

Credit: Typhoon Studios

Hutchinson says he’s had to constantly gain new skills since starting Typhoon, but that his years as a creative director have prepared him well. Over the past decade he’s learned how to give up control, enabling others to do their best work. “I don’t technically do any of the old jobs I used to do, I manage the person that does. You have to give them a box and say, ‘The thing we need is shaped like this, go away and make it better.’ You become an enabler.”

As a leader, he’s learned to be “honest and earnest,” he says. “You’re able to say, ‘Look, it’s fucked up, let’s sit down, let’s fix it.’” Being direct has worked so far at Typhoon, but earlier in his career it occasionally backfired. He recalls a press tour for Spore in which reporters from MTV were annoying him, “not really paying attention.” He decided to give them a shock.

“Someone asked how flexible the editor was, so I said, ‘You can make anything, you could model and fly your penis ship into your vagina house, knock yourself out.’ Suddenly, MTV was paying attention.” Soon after, he got a phone call from his executive producer. Maxis wanted to fire him. “I thought it seemed a bit harsh. But that was the headline on MTV.com: ‘Fly your penis ship into your vagina house.’ They were exploding back at home.… My executive producer calmed it down.”

He’s also putting everything he’s learned about dealing with criticism and failure into practice on Journey to the Savage Planet. The team doesn’t worry about what happens if it all goes wrong, he says, because that would lead to “panicked reasoning.” Instead, they lean into the fact some people will hate it—the game is designed to be polarizing, he says. “I want 1s and 10s [for review scores]. I want some people to bounce off it and say they don’t understand it, and others to say that it’s the best thing ever. They’re the people who remember. My personal goal has always been to be memorable. Whether it’s Spore or Army of Two or Assassin’s Creed III, people have opinions about these games.”

Savage Planet is also a chance for Hutchinson to swerve outside design guidelines that previously constrained him. He’s “made enough games about murdering,” he says, and even though it will have guns, players can expect “something upbeat and positive”—not unlike the mood he wanted for Pioneer. He also wants to recreate the sense of hope and wonder that he had as a child playing Amiga games.

“Every game had that cerulean blue.… It’s like being on vacation,” he says. “So we send you to another planet and ask you to figure it out. They’re the best types of vacations for me: get off the plane with no plan… just get off and wander around. That’s been the driving force of Savage Planet.”

He says he doesn’t know how far the team can take Savage Planet—but they’ll push their ideas to their limits. “We don’t know how much we can get done, how fast we can produce assets, we don’t know the answer to most of these questions. It’s been shippable for six months, but it would’ve been a 5 [out of 10]. We’ll find out how far we can push it.”

And however well it’s received, he knows another chance will be just around the corner. For him, making a phenomenal game isn’t about strokes of genius—it’s about developers working hard, project after project, to do the best they can with their current idea. “I’ve had arguments for years about how to make a phenomenal game, and I’ve always been of the opinion that you just keep making them until one is phenomenal,” he says.

“I don’t think you can sit on one idea in the hope you can grind out perfection. Ideas have a lifetime, a moment, and it’s better to get them out. Moving onto the next one is the easiest way. And then when you have enough you can say: ‘That one was good, this one had its moments, and this one’s not so good.’ You can balance it out.

“And that’s a career.”

Header photo and uncredited photos: John Peroramas for EGM

Samuel is a freelance journalist. When he first played TF2, he couldn’t work out how to fire his gun—until he read a troubleshooting guide. You can find him on Twitter @SamuelHorti.