As you wander the plague-choked Russian steppe town of Pathologic 2, you gather resources. Dig in a trash can for a rusty scalpel or a handful of peanuts, drain a corpse for a bottle of blood, gather herbs rustling on the side of the road. Some of these can be brewed into medicinal tinctures that help diagnose and treat plague victims as you travel, but much of it goes to more practical considerations—bartering with the local children and other townsfolk in exchange for antibiotics or food to satisfy a draining hunger meter. The mysterious plague is the game’s designated adversary, but so are the demands of your own body, which constantly howls for food and drink and sleep. In numerous mixed reviews, the management of these systems has been characterized as extremely hard and overly punishing, as “tedious,” and “nagging” to such a degree that developer Ice-Pick Lodge responded by patching in difficulty modifiers to lighten the impact.

But being difficult, in the traditional video game sense, implies some sort of cathartic win state where the boss is defeated, the level completed, and/or past hardship decidedly behind the player. And in Pathologic 2, passing out enough medicine to one infected district or scavenging enough food to eat your fill never feels like victory. The plague will spread and return, and you’ll grow hungry again. You don’t overcome the game’s dread and misery so much as carve out brief windows of respite—new problems inevitably arise across the story’s twelve in-game days, each consisting of new quests, character interactions, and storylines. As a holistic work, the game bottles a palpable, unparalleled sense of despair and desperation for the way it simply feels to inhabit the diseased town, the suffocating wrongness piled upon your shoulders. The true difficulty of Pathologic 2 is merely existing within a world that the combination of game systems and atmosphere have made to feel near-unbearable, the horror of persisting in the face of horror still to come.

A reimagining of the original Pathologic, Ice-Pick Lodge’s cult game from 2004, Pathologic 2 likewise places you as a healer in an early 20th century settlement on the Gorkhon River. In the original game, there were three playable characters, but as of this writing, Pathologic 2 has just the Harusepx, Artemy Burakh, surgeon and prodigal son to the town’s folk healer. As the Haruspex, you arrive in town to reconnect with your father only to discover that you’re too late; he’s been murdered, and everyone seems certain that you killed him.

The townsfolk are so certain, in fact, that they’ll chase you down on sight and beat you, forcing you to hide by ducking through back alleys and creeping between fences. With the first-person perspective, the surfeit of junk to loot from assorted containers, and residents of Town-on-Gorkhon running you down whenever they spot you, the game’s first day feels like a Bethesda game where you’ve already committed a crime, where the locals are out for blood by default.

Eventually, however, the Town-on-Gorkhon residents move on. At first the center of attention, you’re cast aside according to the whims of a mob. It makes you feel small, like a momentary plaything. “You’re just a character,” Alexandra Golubeva, the game’s former narrative designer, said in an email, “a subject for discussion, and people are eager to vilify or adore you based on their own whims rather than your actions.”

Do some exploring and you’ll find the mob has found blood elsewhere—they burn a woman alive before a crowd of onlookers, and she screams horribly. You can’t save her, but perhaps you can save others; as one of the few doctors equipped to help plague victims, performing medical duties will lead the townsfolk to hold you in higher esteem, and you’ll eventually be compensated in both money and, most importantly, food. You adapt to the circumstances. “We didn’t want the player to feel like they are in the center of the universe because that simply contradicts the main theme of the game,” producer Ivan Slovtsov said in an email. “Pathologic is about being human. It’s about making mistakes and making the best out of the cards you have been dealt.”

“The original Pathologic was incredibly influential here in Russia,” Golubeva said, “so I wasn’t the only person whose idea of what ‘games as art’ can be that it informed.” Neither she nor Slovtsov, who was 18 when the original came out, worked on the first game, but it influenced them greatly. Slovtsov likened the original to his own “philosopher’s stone” of what a game could be, and Golubeva referred to a cosplay art project she did with friends in 2010.

The final product mixes old and new, through a lot of newcomers wishing to retain the experience imprinted so deeply upon them and the more experimental approach of those who worked on the original.

“During the development of Pathologic 2,” Slovtsov said, “one of the main goals was to preserve and reinforce all the great (albeit sometimes incidental) findings of the original, while adding new game systems and mechanics to support them.” It explains, partially, how simply different the game feels in a design sense, despite any surface-level similarities to other works. Pathologic 2’s ideas and experiments are consciously rooted in another time period, and yet it still feels fresh for the fact that so few games approached game difficulty and structure in a similar manner, opting instead for something broader and more accessible.

Sometimes those other games even served as examples of what not to do. “During development,” Golubeva said, “we kept bringing up [The Elder Scrolls V:] Skyrim—a game I personally appreciate a lot, but it served as a common counterexample, because it was not the game we wanted to make. Skyrim offers a lot of freedom at the price of character and situation depth; we went the opposite way. (In hindsight, the comparison seems a bit silly to me; it’s like making a banana cake and constantly reminding yourself that you don’t want it to taste like ham. Duh.)”

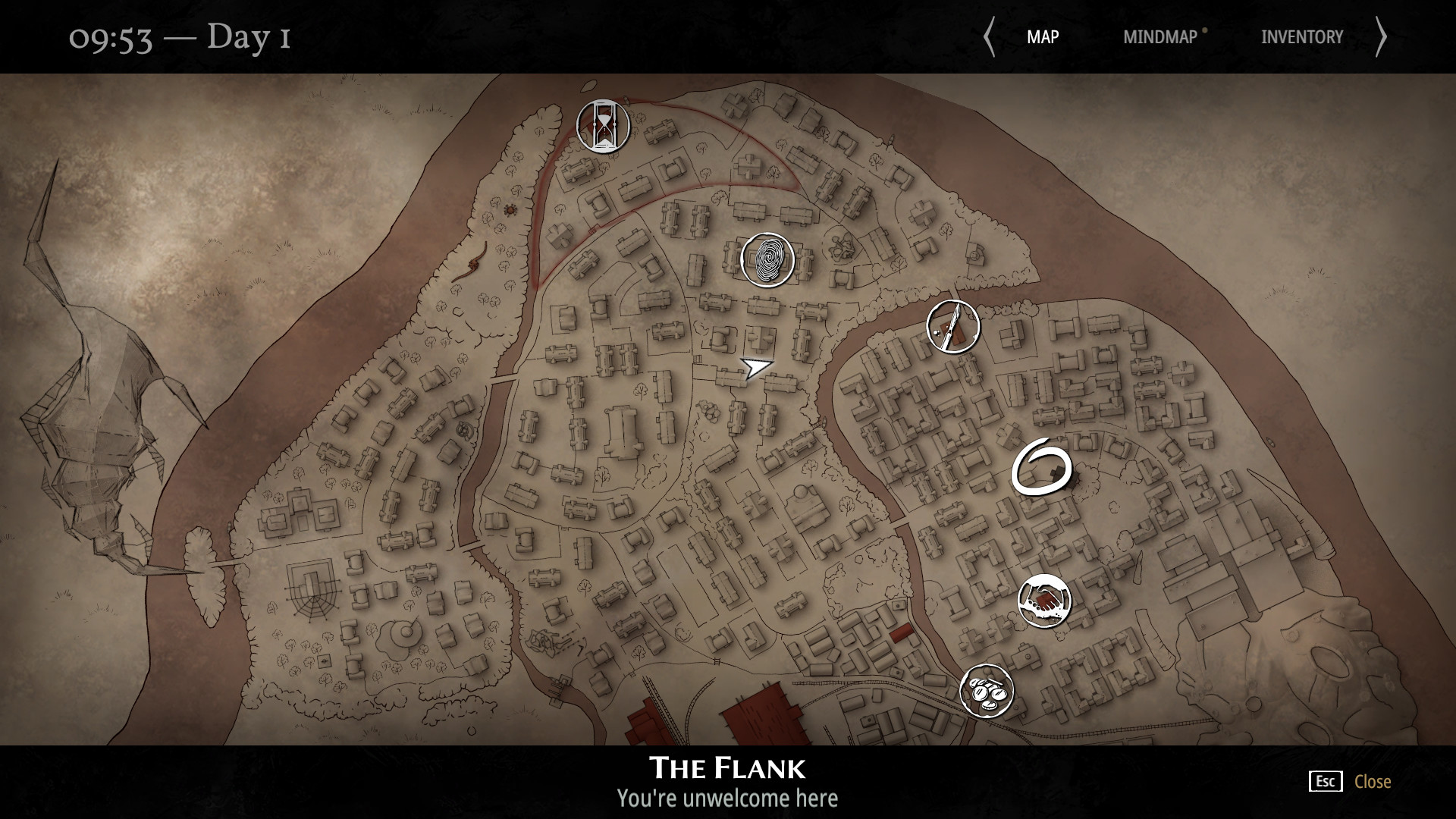

For the most part, there were no concrete influences on Pathologic 2 beyond Pathologic. “It was borderline impossible to draw [direct] inspiration at times, because there were no analogues!” she said. But she does trace the item descriptions to another game renowned for its difficulty, joking, “It would be silly to deny that everyone copied the lore-in-the-item-descriptions thing from Dark Souls—and yes, so did I.” Meanwhile, the evolution of the map, with players uncovering locations as they go along rather than having it all marked from the start was directly inspired, she said, by Hollow Knight.

Even historical references were scant. Slovtsov mentioned the 1910 plague outbreak in Manchuria as a touchstone during development, but Ice-Pick Lodge only became aware of the incident after the first game was already out. Pathologic brought them to the plague in Manchuria, rather than the plague in Manchuria bringing them to Pathologic.

Playing the game requires a period of adjustment from the player. And that adjustment isn’t just to the mechanics and the nature of the setting, like most games, but in how the checklist nature of so many modern free-roam games doesn’t really apply. “Pathologic 2 was designed around an incomplete playthrough,” Golubeva explained. “The idea is for the player to fail, miss quests, and overall play suboptimally.”

A key component of this is the ticking clock. Quests and events are tied to specific days and the moments flow by all the while until the day is over, providing a fixed window for you to either show up and accomplish some stated goal or ignore it altogether. A character might, for example, inform you that your late father’s house is being sold off unless you do something, but it’s a multi-step questline and, in the meantime, you’ll likely have other matters to attend to on the other side of town. “It does create a rather special tone,” she said, “that fits Pathologic 2 so well: that of indifference, of the world living on its own.”

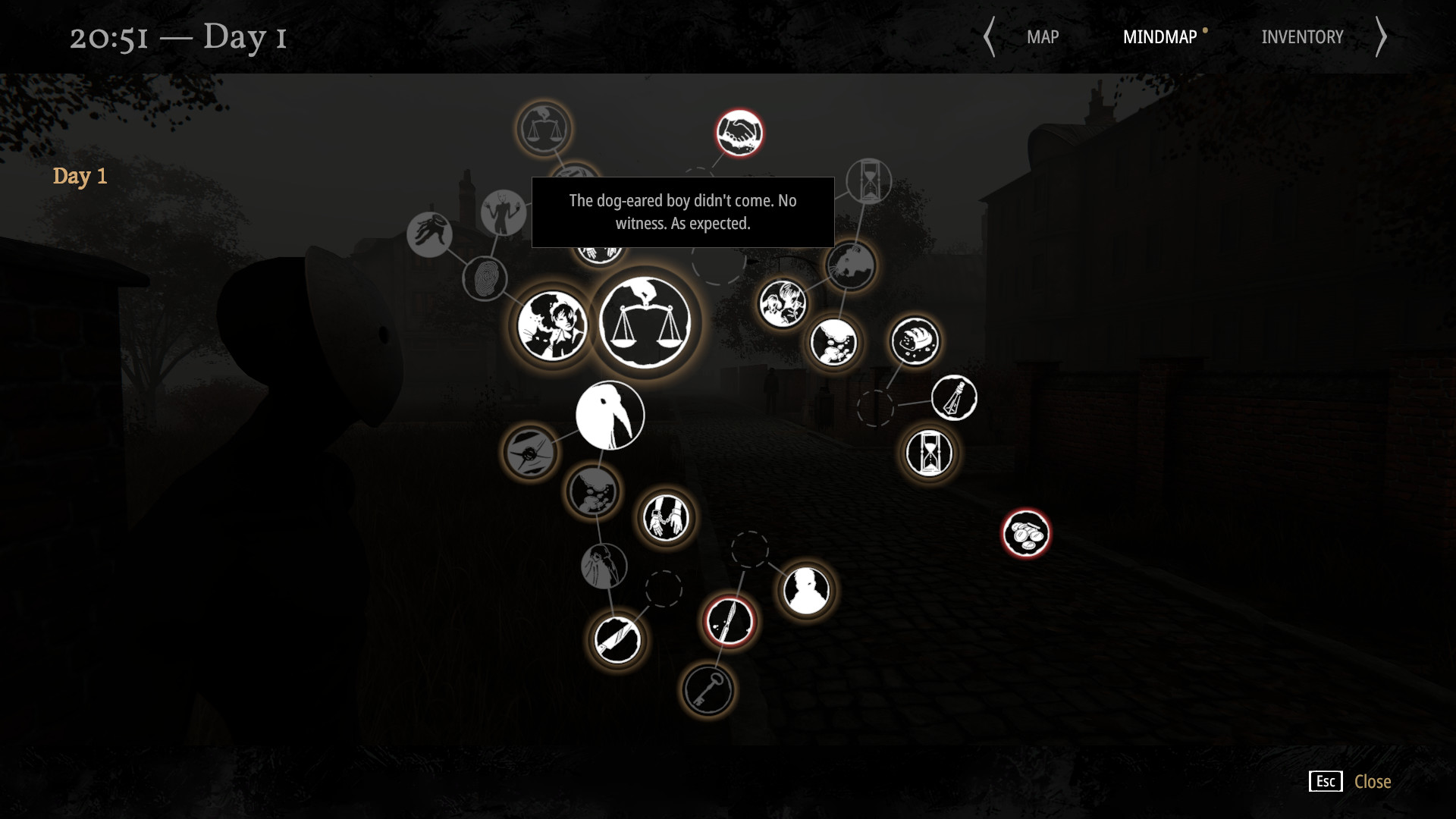

In a presentation transcribed for Game World Observer, Golubeva discusses the game’s mindmap, a tracker for quests and events. It’s a sort of story web, where proximity to other nodes denotes related plot points. In contrast to the original game, there is no marked main quest and instead a scatter of multiple points of interest; you make choices about what to follow up on and what to ignore, and the game, crucially, marks them as complete.

“We didn’t want the mindmap to have holes and create a completionist itch in the player,” Golubeva said over email. “Pathologic 2 is very much a game of uncovering secrets, of weaving knowledge together. We wanted this to feel as natural as possible, and making the mindmap feel ‘complete’ even when you haven’t actually found all possible threads was part of that.”

Sometimes inaction is even the right decision—the house-selling quest, for example, seems designed as a time-waster, forcing you to run back and forth across town and, in the process, teaching you that not all plot threads are worth directly following up on. What is it to you, after all, if someone gets rid of the elder Burakh’s diseased home? It’s one more strange detail players must adjust to, though it feels natural once you grow accustomed to it—few games accommodate blatant inaction, let alone as a correct decision. But for as well as it fits the tone and the atmosphere of the game, it was difficult for the developers to accommodate.

It is, as Golubeva put it, “a shit-ton of headache. Designing a narrative where most events can be missed by simple non-participation is a pain, and there’s no way around it—just a lot of reactivity. There are characters in the story who work alongside the protagonist, who will finish his ‘main quests’ for him—at a price. This was our way of ensuring the most crucial story beats happen no matter what. Aside from that, though? You just have to keep a lot of variables in mind and write many versions of the same dialogues.”

Particularly when coupled with its dreamlike story and nightmarish imagery, the experience of playing Pathologic 2 can feel bizarre and obscure. You might stumble upon a solution by accident or receive advice in a dream while you sleep, and around town there are rituals of ambiguous purpose. Does it accomplish anything to bury a doll in the ground at the behest of some children, to buy a bull that allegedly speaks, or to follow the kids’ rules when exchanging items at their hidden stashes? And even if it all means nothing, do you dare not to do these things and risk finding out?

But the game’s final structure is actually quite straightforward compared to what it once was. “In the beginning of development,” Slovtsov said, “there were no quest markers and many quests didn’t follow the ‘breadcrumbs’ logic where every step… gives you information on what to do next. We wanted to create an ‘old-school’ adventure feel where the players feel like an explorer of both the game-world and the story. Unfortunately, even our internal playtest showed that players are not ready to delve that far into the past of gaming right now, so what we did is make all the ‘main’ story content much more straightforward… while doubling down on obscure optional game mechanics like kids’ stashes, blood-drinking roots, hidden optional events, etc.”

In the final game, the plague spreads in a fixed pattern to accommodate the storytelling. Originally, though, it was based on ambiguous factors the player wouldn’t have been totally privy to—dropping an infected item on the ground, speaking to townsfolk while infected, even just the number of trash cans you’ve looted. “Inevitably,” admitted Golubeva, “some people note that it sounds really cool—and it does, which is why we tried this approach, but more than anything, it was a slog to play.”

“Many games these days use similar mechanics and problem/solution patterns, so players often ‘tune out’ while playing them on autopilot,” Slovtsov said. “From the very beginning, one of our design goals was to make players aware of what they are doing at every step.” This meant being clearer about the game mechanics, quests, and locations. For example, while walking through an infected district you might hear the cries of a baby. There are rewards for rescuing an infant from the plague, but without map markers to indicate the baby’s location, playtesters assumed it was merely ambient noise, a complement to the droning music of the infection that sounds as if the black particles in the air are all somehow giving a doom chant. It’s darkly funny, in a way; the atmosphere is so thick with dread that a wailing child fits right in.

Much of the resulting game asks you to make compromises, to weigh your current knowledge of the mechanics against the potential for progress. Muggers in white face paint roam the streets at night with knives, clashing with town guards and chasing after you if they spot you. Though you’ll likely have some sort of weapon by the time you encounter these characters, weapons aren’t durable. Repairing them eats resources you might otherwise trade, and carrying a back-up takes valuable inventory space. Sometimes, it’s better to flee. As the clock ticks down, after all, there’s likely some other task you have to accomplish.

And yet fighting a mugger can bear fruit: Even if he only has a sewing needle and a button in his pockets in addition to some coins, such apparently meaningless objects are useful in the town’s barter economy. Children, naturally, love sharp objects and are willing to trade a bullet they’ve found on the ground for a sewing needle or pair of rusty scissors. Rather than firing the bullet from your gun (if you acquire one), you might then trade the bullet to a guardsman for some stale bread that’ll keep you fed just a little while longer, at the expense of gaining some thirst. If you’re truly desperate, maybe you’ll give up your lockpick.

“At the beginning of the game, we focused on explaining all of the core game mechanics as clearly as possible (and I believe we’ve managed that) but when that’s done, we leave the player alone with this newfound knowledge,” Slovtsov said. And with that knowledge, you make further discoveries over time and in the moment, like how muggers found on the ground, dead, never seem to have anything on them. Fight one alongside a guard and you’ll learn why: The guards aren’t above going through a mugger’s pockets alongside you. The presence of a guard certainly provides backup and protection, but it also presents a potential liability because, after all, you’re one of the town’s few doctors. You need the supplies more than them. It’s beneficial to fight in back alleys away from prying eyes, if you’re confident enough in your own abilities and hopeful enough that you won’t be ganged up on.

“It is never a binary choice with predictable consequences that you make with a press of a button in a dialogue,” Slovtsov said. “It’s just you trying to be aware of your actions and taking responsibility for the consequences. You might cause the death of a key NPC by selling all of your medicine that you could have used to save them. Instead of that, you go and buy surgical tools to cut out organs, in hopes of making a cure that will save more people down the road.

“The difficulty of Pathologic 2 comes not from the fact that you have to [metaphorically] kill a dragon,” Slovtsov continued. “The difficulty comes from the fact that you have to remember that while you will be fighting the dragon, the princess in the other castle will face mortal danger and probably die.”

Of course, fighting a dragon is in itself no easy task. Upon release, Pathologic 2 faced criticism for how punishingly quickly its various hunger, thirst, and other meters tick down, eventually causing damage over time. Upon death, the local theatre director revives you, tut-tutting your performance while imposing a permanent penalty like a lowered health bar for the next attempt. This is the intended outcome: that you try, die, and try again—albeit not before arguing with the director over whether his punishments are even particularly fair and, in the process, getting into a debate that considers the very nature of role-playing within a video game. But for many people, it also felt merciless and inaccessible.

Initially, the developers were hesitant to make any changes. Golubeva said the game “strives to be a Gesamtkunstwerk, i.e. ‘an all-embracing art form,’ and by that I don’t mean self-praise; we tried to create an art object where every component served its overall purpose. You wouldn’t turn off the sound for a (non-silent) movie, or replace the soundtrack with something to your liking; so why would you turn off gameplay elements in a game?”

As Slovtsov said was the team’s goal, the game forces you to think about every decision, and the difficulty is an intrinsic part of that, balancing the need for food against the need to meet with the children in dog masks at the other end of town against the need to give another character at another end of town some medicine because their district is infected.

“In games like Pathologic 2,” Slovtsov said, “balance is not just a mathematical equation.” He noted that the barter economy began with an Excel sheet that calculated things like the player’s potential resource accumulation, from which prices and drop rates emerged from—but these initial impressions had to be re-examined once they actually played the game themselves.

“It’s a feeling that is hard to put into numbers without playing the actual game. That is why there is a debate around the game’s difficulty, since it is balanced not completely around the numbers, but around something highly subjective.”

And that subjectivity is ultimately what led Ice-Pick Lodge to relent. Golubeva drew a comparison to other mediums: “There are certain kinds of art that require skill, education, and so on to consume, like classical music that can be hard to appreciate if you know absolutely nothing of musical theory. Anyone with enough time and access to information can educate themselves to appreciate classical music better, but it may be physically impossible to improve one’s twitch skills or sense of time. And it’s not fair to just exclude people who can’t—like, it’s not right on a fundamental level. Which is why we decided to add difficulty sliders in the end. If the idea behind these settings is that all people are different and we can’t predict their level of skill, then it’s only natural to provide granular settings so that anyone could find the right combination.”

The current form of Pathologic 2, then, is remarkably malleable in terms of difficulty. It comes with a disclaimer about the intended experience and offers detailed explanations of each slider’s function. You can, Slovtsov noted, even make the game harder by increasing the damage output in fights. But the triumph of Pathologic 2 is that, even with these mechanics cranked down to a tamer level, it’s difficult to plan anything. On an initial playthrough, that’s because things keep changing, the economy upended by the sudden introduction of meal vouchers or the disappearance of the children, who could be relied upon to cough up something useful in exchange for literal peanuts.

But it’s also a result of the game’s obscurity, a staunch refusal to tell you everything. It’s tough to hoard food because there’s no concrete number for how much of the hunger and thirst meters will be refilled by a tin of meat or a bottle of water; just “a lot” or “some” or “a little.” Perhaps your attention even shifts elsewhere during your careful supply-gathering and you waste too much precious time, or you run out of inventory space while your storage closet is on the opposite end of town. All the while, the clock ticks down, forcing decisions and compromises without an obvious path of which storylines to follow up on, or which ones you can afford to ignore. You have to manage your time, and there’s never enough of it.

“Like [2009 horror game] The Path, we don’t actually want the players to just follow the road,” Golubeva said. “To this end, some quests are detrimental, some are hidden, and some of the most beautiful and intriguing moments (like seeing the real universe from the Polyhedron) have no gameplay merit or even practical connections to the plot. Some subplots are rather deeply hidden, some events only happen if you explore a lot… a big world only feels alive if it’s rich with secrets.” The game’s DLC story, The Marble Nest, lessens the survival mechanics in favor of storytelling, but its mystery gets no easier to solve—how do your actions affect the world around you? Do they at all? How can you be sure, without just doing it all over again?

One character describes Town-on-Gorkhon as “a crucible for remaking the mind and spirit.” In-universe, the layout of its streets, the design of the buildings, and even to a degree the plague itself is a ruling-class experiment upon the populace. The effect of Pathologic 2 as a cohesive work is similar: a crucible for the player where each disparate element is calculated to exert pressure, from the mysteries of its interlocking storylines to the horrifying atmosphere of decay and despair that makes even a journey out onto the empty plains feel unsettling. It is so single-minded that lowering the barriers of traditional video game difficulty does not lessen its suffocating impact.

If, as Slovtsov said, the game is about being human, then being human in this case is to be confronted with your limitations as a player, as a decision-maker, as a person. To face the enormity of the world’s mistakes and struggle against them, never truly feeling triumphant; there are no obvious solutions for remaking the world. “I fully understand how [power fantasy] games are considered more ‘fun’ and people prefer them,” he told me. “But to communicate with a player on a more personal level, we had to distance ourselves from that approach.”

“Designing a narrative like this goes against basic rules of game design,” Golubeva said, “and we made a point to create a number of situations where your choices and actions clearly matter and have visible consequences. But it can actually be interesting at times to make the world indifferent. And realistic, too.”

Some quotes have been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

All images from Pathologic 2. Credit: tinyBuild.

Steven Nguyen Scaife is a grumpy freelance writer based in the Midwest. He has covered a variety of pop culture for outlets like The Awl, Buzzfeed, Fanbyte, Polygon, Rock Paper Shotgun, and others, while doing regular reviews for Slant Magazine. He does not yet own a cat and tries to be funny on Twitter @midfalutin.