It’s been 20 years since I traveled to the moon, defeated an evil Magic Emperor, and fell in love.

Like many gamers of a certain age, I was obsessed with Japanese RPGs during the mid-’90s. I played the Chrono Triggers and Final Fantasies, Suikodens, and Breath of Fires, but few games have stuck with me over the years with the same intense emotional connection as Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete.

A PlayStation remake of a Sega CD game called Lunar: The Silver Star, Lunar: SSSC was developed by Game Arts and released in North America in 1999. It tells the story of young Alex, an erstwhile adventurer with dreams of following in his hero’s footsteps to become the next Dragonmaster. At his side is Luna, his childhood friend with a literally magical voice, and entrepreneur-in-the-making Ramus. Together, they set off on a journey that will change their world.

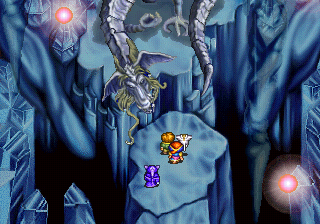

Credit: Working Designs via LunarNET

What makes Lunar: SSSC worth celebrating on its 20th anniversary? For me, the answer is very personal. A huge part of my youth was spent playing through Japanese RPGs with friends. I’d lug my PlayStation and trusty Commodore 1702 monitor to my friend’s house where we’d set up side-by-side and play through our own copies of Lunar: SSSC—comparing notes, racing through dungeons, and trying not to spoil ourselves by watching each other’s screens too closely. It was an immensely satisfying experience and helped Lunar: SSSC stick with me in a way that even my other favourite Japanese RPGs of the time didn’t and cemented a lifelong friendship.

While everyone else was writing Final Fantasy VII fanfic, my first serious attempt at writing a novel was Lunar fan fiction with the serial numbers removed. Two decades later, Alex’s epic adventure to become Dragonmaster holds a special place in my heart. Like him, I was a kid on a journey trying to discover myself.

But there’s also a broader answer, because Lunar: SSSC, like the Sega CD original, encapsulated the bright and vibrant style of 16-bit Japanese RPGs. It’s like a Saturday morning cartoon: effervescent and earnest, and more concerned with adventure and kindness than the grittiness and antiheroes of some of its most popular contemporaries.

When asked about Lunar’s greatest selling point in a 1996 interview with GameFan magazine, Game Arts’ COO at the time, Toshiyuki Uchida, said, “I think that it will make everyone who plays it very happy.”

It made me very happy, indeed.

Silver Star History

Sega’s CD add-on for the Genesis/Mega Drive, known as the Sega CD in North America and Brazil and the Mega CD everywhere else, was not long for this world. It only sold about 2.24 million units worldwide before Sega dropped it to focus on its upcoming 32-bit system, the Sega Saturn. But despite the system’s overall lack of success, Lunar: The Silver Star managed to be one of its few shining stars.

“It took the market by storm,” wrote Sam Pettus for Sega-16 in July 2004. “Lunar was the first mega hit Mega CD title, selling well over 100,000 copies (its entire production run) during its initial market debut. Sega of Japan directly attributed increased consoles sales to Lunar, and it caused many companies in the industry to sit up and take note of the system – including a certain American importer of Japanese RPGs looking to back the new system with the rather unusual name of Working Designs.”

Reviewing Working Designs’s North American version for GameFan, Skid called it “far and away the best RPG I have ever played,” and GamePro‘s Lawrence of Arcadia claimed Lunar: The Silver Star was “not just the best Sega CD RPG ever, but one of the best on any Sega system.” Fans and critics alike were, ahem, over the moon.

Under the leadership of its president, Victor Ireland, Working Designs piggybacked off the series’ success on Sega CD and localized Lunar: SSSC with a level of dedication and professionalism that was rare at the time. The PlayStation remake hit North American shores on May 28th, 1999, just a few short months before the hotly anticipated Final Fantasy VIII. While the Sega CD original had a small, passionate fan base, Lunar: SSSC found new life for the series with the suddenly enormous North American audience for Japanese RPGs spawned by the huge and unexpected success of Final Fantasy VII two years earlier.

From the moment I saw its oversized cardboard box, I knew Lunar: SSSC was different. Its gorgeous embossed cover flipped open to reveal more details about the game—which came alongside a hardbound instruction manual full of more art, interviews with the creators, localization notes, and a walkthrough of the game’s early hours. Just opening the box felt like a high-quality experience, and that feeling continued as you were greeted by the game’s fully animated opening movie. These sorts of collectors editions are common now, but nobody was doing them in 1999.

Where other games at the time were going big and splashy, Lunar: SSSC maintained the roots planted in the early ’90s Sega CD original—offering a battle system that seemed simple on the surface (each character only had access to a handful of spells/abilities, there were no limit breaks, no splashy animations), but proved to be deep, tough as nails, and, importantly, fast. While many of its contemporaries like Final Fantasy VIII used smoke and mirrors to hide load times as they drew up 3D models, Lunar: SSSC thrust players into the action within seconds, and thanks to a robust auto-battle mechanic they were bashing enemies almost immediately.

“Lunar made great counter-programming for the more progressively designed RPGs of the era by sticking to a more traditional structure and look,” Jeremy Parish told me when I reached out to ask him about Lunar: SSSC‘s place in JRPG history. It had no CG cutscenes, he continued, “just hand-drawn sprites and a combat system that seemed to owe a lot to SSI’s Gold Box D&D games from a decade prior. At the same time, the remake made a few forward-thinking quality-of-life changes, like getting rid of random battles.” Lunar: SSSC took the cult-classic experience of the Sega CD original and “struck a great balance between old-fashioned and contemporary.”

I first crossed paths with Parish, EGM alumnus and current co-host of the retro gaming podcast Retronauts, on the official Working Designs message boards back when he was known colloquially as ToastyFrog. I came for the games, but stayed for the tight-knit community of fans eagerly waiting for the localization company’s next U.S. release. Over the years, Parish became one of the most prominent voices covering retro games.

“The Sega CD version had its charms,” Parish told me, “but once I’d played the remake I never felt an urge to go back to the original.” The PlayStation release improved the user experience with a lot of quality-of-life improvements: “No more random battles, no more silent gaps as the background music looped, no more ALL-CAPS CONVERSATIONS, nicer visuals.” Lunar: SSSC took the story laid out in the Sega CD original and fleshed it out in many ways, including providing new layers of complexity to the game’s antagonist, Ghaleon.

At the time, Peter Bartholow of Gamespot called it “a must-buy for fans of the series,” lauding its story and gameplay. Similarly impressed, The Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine said, “Don’t mistake this for some nostalgia-warped vision of how all the ‘real’ RPGs ended with the death of the 16-bit machines—Lunar deserves to be played based on its own merits.” As the lead reviewer for EGM, John Ricciardi praised the remake. “It was well worth the wait. Even if you played through the Sega CD version, I still highly recommend you check this version out, because a lot has changed.” Ricciardi praised the game’s story and dialogue, going so far as to say Lunar: SSSC was “easily the most well-written RPG” he’d ever played. Fellow reviewer Che Chou was new to the series but agreed with Ricciardi. “I was surprised at how well the game holds together for being six years old,” he said. “As usual, WD’s trademark humor is present, but it doesn’t seem to override or distract from a very engaging story.”

Lunar: SSSC allowed series fans and newcomers to revisit a classic from a new perspective. Now, 20 years have passed since the remake’s release, and gaming has changed immeasurably in that time. Pop culture, and the standards we hold it to, are different. Japanese RPGs have become a lot more complex, driven by myriad systems, and generally appealing to smaller, niche audiences. In this contemporary light, Lunar: SSSC’s successes—and flaws—are more obvious than ever.

Now you’re here, now you’re not

Lunar: SSSC sold over 220,000 copies in the U.S. in 1999, placing it third among RPGs for the year behind only Final Fantasy VIII and Planescape: Torment. But Final Fantasy VII had cast a long, dark shadow over the JRPG landscape. It ushered in a new era of prerendered backgrounds, gritty, futuristic storytelling, and darker tones.

Lunar: SSSC was decidedly not that. One of the most remarkable aspects of Lunar: SSSC‘s story isn’t just that it found success, but that it managed to carve a bright, friendly place for itself in post–Final Fantasy VII world. How did this Saturday morning cartoon, with its bright visuals, sweet story, goofy enemies, and pun-filled dialogue do it?

“Working Designs did a great job of positioning Lunar in the wake of Final Fantasy VII,” Parish said. “There was a lot of newfound enthusiasm among PlayStation fans for JRPGs, and at the same time anime had really begun to enter the mainstream. The Lunar remakes managed to touch on both of those things, thanks to the extensive, re-animated cutscenes that helped relay the story.”

Despite their vast differences, Lunar: SSSC and Final Fantasy VII share one foundational plot element: The hero loses his love interest.

There are a lot of similarities between Luna and Aeris—they’re both healers with a mysterious past and quiet personalities—but the differences in the way the games handle their respective fates is a clear illustration of how the Japanese RPG was changing by the time Final Fantasy VII released.

Few moments in gaming history can match the cultural impact of Sephiroth killing Aeris at the end of Final Fantasy VII‘s first disc. The series was no stranger to killing (and reviving) its characters, but never with the emotional stakes and impact as this defining moment. After picking myself up off the floor, my hormone-soaked teenage heart pounding, I was filled with a righteous anger. Chasing Sephiroth had so far been an exciting adventure, but now it was personal. Catharsis in this instance came through vengeance. Cloud’s loss of Aeris could only be satisfied by reciprocal violence.

On the other hand, Luna is kidnapped by Magic Emperor Ghaleon in a similarly shocking moment about a third of the way through Lunar: SSSC. Where Final Fantasy VII motivates the player through anger, Lunar: SSSC instead challenges them to press forward, not just to defeat Ghaleon, but to save Luna even as she unwittingly becomes the Magic Emperor’s greatest weapon.

Toshiyuki Uchida told GameFan he wanted players to fall slowly in love with Luna, so that “the feeling of ‘I have to save her’ comes naturally.” Boy saves girl is a trope as old as time, but Lunar: SSSC is a brilliant example of how to motivate the player by building a strong emotional connection between them and the characters.

“The late ’90s were all about edginess and attitude,” Parish told me, “and most RPGs that began to make their way to the U.S. at the time keyed in on the dystopian aspects of Final Fantasy VII. Lunar wasn’t about that. It had a sincerity and sweetness to it that set it apart—I mean, the big plot event of the first chapter hung on one of the main characters singing a ballad. Even with Working Designs’ snarky localization, the good-hearted spirit of the game still shone through.”

A proactive protagonist

“Whatever.”

The recent Final Fantasy VIII remaster has introduced a whole new generation of gamers to Squall Leonheart’s catchphrase. His ambivalence towards, well, pretty much everything, was one of the game’s hallmarks and helped pave the way for antiheroes like Yuri Lowell from Tales of Vesperia and Ryudo from Grandia 2. Whether he was a true antihero or just wanted to be perceived that way is up for debate, but he took Cloud’s antipathy to a whole new level. At least Cloud was fiery in addition to being a lone wolf who cared more about himself than saving the world from eco-disaster. Squall was the prototype of a moody teenager who didn’t know how to process his emotions.

To a teenager like me, I felt seen. Squall and Cloud were edgy, and they pushed back when other people told them what to do. But their reluctance also meant they were often reactive protagonists. Instead of driving the story forward, they responded to the actions of others and the events unfolding around them.

Alex was different.

“I don’t remember when it started exactly,” he says during the game’s opening, “but the dream of having a fantastic adventure in far-off places grabbed my heart early and has yet to let go.”

Alex is sitting quietly at Dyne’s memorial, meditating on stories of his hero, and yearning to be able to do good in the world. He doesn’t wait for trouble to find him. Instead, alongside his ambitious best friend, he sets out to find adventure himself by exploring a nearby cave, chasing rumours of a dragon. It’s a trope, to be sure, and, in the post-Final Fantasy VII world, when gamers were yearning for moody antiheroes, it might have felt quaint, but it immediately drew me into Alex’s world. There was a kindness to Alex’s journey that I hadn’t found in any other games. I wanted to join him as he pushed forward through the world, chasing his goals, and helping others along the way.

In an interview for the game’s North American instruction booklet, scenario writer Keisuke Shigematsu revealed that the original concept for Lunar: The Silver Star was to tell the story of a young boy who travels the world spreading democracy. This evolved into a more traditional “good versus evil” plot by the game’s final release, but you can still see the influence of the original idea in Alex’s desire to reach out and change the world because he wanted to help people.

One of the game’s most shocking moments comes at the end of the first disc when Nash, a foppish wizard in training, betrays the party by destroying its airship. It hits the player like a hammer to the gut, but it also feels inevitable. “Characters in the Lunar world are not perfect people throughout the game,” Ryousirow Hasukawa, who was responsible for much of Lunar‘s scenario development, stated in an interview with Lunar.net. Just like people in real life, “they have weaknesses and faults.” Nash doesn’t betray his party because he wants to hurt them, but just the opposite: He’s afraid of the coming confrontation with the Magic Emperor and believes he can save his friends from what he perceives as a hopeless fight. He’s ashamed of his actions, and acts from a place of weakness, but his motivations are a complex mixture of fear and love.

Press X to talk

Lunar’s not only a story about Alex and his party. It’s “also about all the townsfolk and other inhabitants who live on Lunar,” said Hasukawa. “They have backgrounds of their own. We had this in mind when we were developing the game.” The goal was to make the game stand out from its peers by providing depth to the world. NPCs weren’t simple set pieces or window hangings, but instead did a lot of heavy lifting when it came to providing world building, plot momentum, and even character development that fell outside the plot’s main path.

It wasn’t unusual, even during the PlayStation era, for NPCs to wander around saying the same thing from the beginning of the game to the end, like they were caught in a time stasis. Sometimes multiple NPCs would utter the same useless and often poorly translated bit of fluffery. “Aren’t cats great? This one’s a little big, huh?” a little boy says to Cloud in Wall Market early in Final Fantasy VII. Game Arts and Working Designs wanted more than this. Your characters, including Alex, often banter back and forth with townsfolk and other NPCs. They joke about Nall’s love of fish in Lann, cringe their way through Meryod, and stand out as tourists in Meribia. It’s a brilliant example of how the tone and texture of a story can be enhanced for the players who go out of their way to look for it.

At a time when the biggest JRPG in the world suffered from a dreadful translation, Working Designs saw an opportunity not just to bring Lunar: SSSC to a new and larger audience but to make it a full, robust experience, something that elevated what many gamers thought was possible from a translation. This wasn’t a slapdash operation—it was a full-bore, highly polished localization, which, at the time, was nearly unprecedented.

“Anyone can do a straight translation,” Ireland told PSIllustrated at the time. But doing so can often miss the game’s original intent and mood. “To understand the mood, emotion, and feeling of a piece and convey that to a completely different mass audience in a completely different culture is quite difficult.”

As someone who spent a huge chunk of my childhood and teenage years buried in novels, it was refreshing to play a game that had obvious care and attention paid not only to its story (because games before this had good stories, even if good localizations were few and far between), but its writing and localization made me realize that games could sit alongside books as equals. Lunar: SSSC stood alongside the work of Square’s Richard Honeywood (Xenogears and Chrono Cross) and Alexander O. Smith (Vagrant Story) at the pinnacle of localization at the time. In the 20 years since, we’ve seen some truly marvelous writing—from Dragon Quest VIII, to NieR and its sequel, to Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door.

Uchida wanted Lunar: The Silver Star to be “a piece of art that happens to be expressed as a video game.” But without dedicated and talented partners like Working Designs, English speakers never would have experienced this. Two more recent remakes—2002’s Lunar Legend on Game Boy Advance and 2010’s Lunar: Silver Star Harmony on PSP—are testaments to how much the game suffers with mediocre localization.

Broken Designs

But that’s not to say Working Designs’ work was perfect. At the time, many fans were critical of the Western localizers for putting too much of their stamp on the final product, making the experience of playing Lunar: SSSC very different in English versus its original Japanese release—and not just in terms of story, dialogue, and writing, but by changing fundamental elements of the gameplay, too.

It’s easy to get lulled into complacency by Lunar: SSSC‘s sugary visuals, humour, and story. It wants you to feel invigorated and energized. But, in reality, especially compared to the Final Fantasy games of the time, which were pretty breezy outside of optional battles, Lunar: SSSC is tough as nails. Especially the Western version. Working Designs took their role as localizers seriously and made many, many tweaks to the gameplay, almost all of which aimed at making the game more difficult than its original Japanese release. Enemies do a whopping 45 percent more damage, and provide 14 percent less experience and 10 percent less silver when defeated. These changes turn the game into a grindfest, requiring players to tiptoe into dungeons, push through until they’ve burned through their resources and retreat to town to restock. It adds a significant amount of artificial playtime to the game, and feels at odds with the emotions the storytellers and visual artists were trying to convey.

In many ways, Lunar: SSSC is a quick, snappy experience, which makes Working Designs’ gameplay tweaks all the more incongruous. Though a longer game would probably have been a selling point at the time, Working Designs’ gameplay changes markedly lengthened the playtime, to the point it created frustration for new players—and required the plot to take a backseat to simply grinding enough gold to properly outfit the party for the upcoming dungeon.

Still, time has been kind to most aspects of Lunar: SSSC. Its story holds up nicely, the graphics are still beautiful, and the battle system is simple and fun. But there’s one element that was difficult to ignore back when it was released and impossible to ignore now: the jokes.

One of the common criticisms leveled at Lunar: SSSC, even at the time of its release, was its reliance on fourth wall-breaking pop culture references—which included, but weren’t limited to, Bill Clinton and M&Ms. Game Arts and Working Designs created a rich world that felt real and lively, but chatting up an NPC and hearing a joke about the Tootsie Pop owl ripped you right out the experience.

These pop culture references and puns are regrettable, but what really sinks the ship is the constant hammering of humor that can best be described as juvenile. (This in itself is ironic. Ireland admitted the humor was added by the localization team because he finds Japanese humor to be too direct and “infantile.”) Jokes about masturbation, regular objectification of women played for laughs, and a transphobic introduction to one of the game’s main characters are only some of the examples that might’ve made me laugh when I was 15 but had me groaning while replaying the game at 35.

It reeks of a desperate attempt to stand out from the crowd, as though the game were ashamed of its cartoony graphics and relatively lighthearted story at a time when Final Fantasy VII and Xenogears were taking players on darker journeys. It’s too bad, because Working Designs’ writers really knew how to hit the sweet spot with the game’s more serious and touching moments. As Parish pointed out to me, the localizers relegated most of this humour to NPC dialogue, making it semi-optional and keeping the game’s main story beats and emotional core relatively intact. Lunar: SSSC had all it needed to stand the test of time against its peers without the dick jokes.

“At the time—before referential humor was bludgeoned by Family Guy and The Big Bang Theory—no one was writing RPGs like that,” said Parish, “and very few publishers took the time to rework games so comprehensively for the U.S. market unless they were censoring content to meet Nintendo of America guidelines. It’s easy to criticize Working Designs, but they were working from a sincere place.”

I’m going on an adventure

“Sincere” is perhaps the single best word to describe Lunar: SSSC. It wears its heart on its sleeve, and is wrapped around a core of sweet, sticky kindness that very few RPGs have ever replicated. Coupled with Noriyuki Iwadare’s infectious and upbeat soundtrack, this all lends to the irresistible feeling of adventure that permeates the game from start to finish. Thanks to Alex’s go-get-’em personality, the rich world, the swift pace, and the bright visuals, every moment playing the game feels like an adventure. “[We] were trying to make each other laugh,” Ryousirow Hasukawa recalled of his work with his fellow scenario writers while speaking with Lunar.net.

GungHo’s recent release of the Grandia HD Collection on the Nintendo Switch puts the spotlight on Game Arts’ Lunar follow up, Grandia, which was in parallel development with Lunar: SSSC and very much a spiritual successor to the Lunar games. It features a best-in-class battle system that takes some of the core elements of Lunar’s battle system, like positioning and character-specific skills, and expanded on them with roaring success. More importantly, though, Grandia also built on Lunar’s foundation of great characters, excellent NPC dialogue, and a bright, colourful story with a kind heart and adventurous bones. It’s easy to look at Grandia to see what the Lunar series would have become if the original Lunar 3 didn’t sink under the weight of the legal disputes between Game Arts and Studio Alex. (For more on that, check out this decade-old thread on the Lunar.net forums.)

Lunar: SSSC‘s impact beyond the 32-bit era is difficult to track. Even later Lunar games, like the forgettable Lunar: Dragon Song on the Nintendo DS, seem to forget the lessons of their forebears. “It’s a shame,” Parish said. “Lunar and especially Lunar 2 were fantastic examples of how to elevate bog-standard takes on a genre through considerate tweaks and genuine care. Both games were much more memorable in practice than they sounded on paper.”

Perhaps the modern series that best captures Lunar’s spirit is Falcom’s Trails in the Sky. In 2015, Kotaku writer Jason Schreier called Trails in the Sky the “best JRPG of the decade” and directly likened it to the Lunar games. He lauded the game for its characters, deep battle system, and writing. Sound familiar? Trails in the Sky is “a game for anyone who wants to dig into a brand new world and just explore, talking to every NPC and checking every hidden corner for secrets.” From guardspeople to vagrants populating seedy inns, nearly every NPC in the Trails games has a name, personality, and backstory. “Keep talking to them between every plot point and you might see them fall in love with one another, or get married, or go traveling to other cities where you can find them and chat with them more.”

Like Lunar, an impressive amount of ancillary world- and character-building is handled by NPC dialogue. The game’s party are active participants in conversation, and the world is filled with rich, interesting NPCs that reveal many facets to the world and the characters that would be glossed over or missed entirely in other JRPGs.

To the moon

“How the hell are you selling that much of this little 2D RPG?”

Ireland was probably paraphrasing Sony’s end of things in this interview with Lunar.net, but it’s a good question. How did a remake of a niche 2D Sega CD game during the halcyon days of moody protagonists, pre-rendered backgrounds, polygonal characters, and interactive CG cut-scenes, become such a success?

At the time, Lunar: SSSC was by far Working Designs’ highest selling release. “It’s not even close,” Ireland said. His answer to Sony’s question about how Working Designs was selling hundreds of thousands of copies was simple: “It’s all about word of mouth. All the Lunar fans keep talking about it and people want to experience the game and Lunar has a great reputation since almost everybody who played the original loved the game.”

Lunar: SSSC thrived in a post-Final Fantasy VII world because it offered players an experience that speaks to our desire for adventure and kindness, for helping others, and feeling invigorated to keep pushing forward. It was the perfect antidote to Square’s hyper-serious turn. Lunar: SSSC felt real not because of grown-up characters, curse words, or themes of climate change and theology. Instead, it felt real in the same way our favourite Saturday morning cartoons felt real: These were characters we could root for and aspire to be.

We played because we felt like we were making a difference. Not because the world was crumbling and we were the only ones who could keep it together—but because we pushed forward toward our own with a determined goal.Uchida wanted players to fall in love with Luna, but what we really fell in love with was Lunar.

Header image: Working Designs via LunarNET

Aidan Moher is a Hugo Award-winning writer and editor, with work appearing on Kotaku, Barnes & Noble SFF Blog, Tor.com, and elsewhere. He lives on Vancouver Island with his wife and kids, but you can more easily find him on Twitter (@adribbleofink) or his website—where he talks obsessively about fantasy novels, scanlines, and 16-bit JRPGs to anyone who will listen.