Video games have looked to the military for inspiration for more than four decades—at least as far back as 1974’s Tank. Contemporary shooters that meticulously recreate the weapons, equipment, and uniforms of soldiers represent many of the biggest games on the market today, their profiles only elevated by the recent surge of esports. Now, however, two organizations are looking to bridge the gap in the opposite direction.

The Military Gaming League and U.S. Army Esports seek to link the gaming communities that exist among the active duty military and veterans with the wider esports world. These organizations bill themselves as using competitive play to humanize the military and build a more nuanced representation of those who serve. One could be forgiven for being dubious about those motives. In 2018—the same year both MGL and Army Esports began official operations—the U.S. Army failed to meet its recruiting goal for the first time since 2005, when the Iraq War was at its height.

There’s a real and justified concern about the American military-industrial complex moving so directly into the world of gaming—a space predominantly filled with young people, no small number of whom are lonely and impressionable. In talking to the individuals running these new military esports ventures, however, it becomes clear the reality is far more complex.

“I saw there was a space there, an emptiness, where military service-members and veterans didn’t really have a space to play with each other, compete, make their own way through the esports world,” Travis Williams, chief executive and co-founder of Military Gaming League, told EGM. “That’s how I began thinking about having a league that’s catered specifically towards service-members and veterans but that also caters to their emotional needs of the individual, helping with PTSD and stuff like that.”

Moving away from active service in 2017, Williams began working for various nonprofits that assist veterans before deciding to found MGL. As an avid gamer himself, and knowing how many service members also played, he wanted to merge the outward-facing support of a nonprofit with the passion and collaborative nature of competitive video games.

Primarily centered on esports, MGL is probably more accurately described as a gaming community for anyone who’s currently serving or has previously served. Once your service has been verified, you’re welcomed in with open arms, with a private Discord as the main forum for members. From there, MGL organizes “Branch Battles,” which separate teams by service branch—Air Force, Navy, and so on—and preferred games. Those who want to compete seriously can do so, while those who don’t can play casual multiplayer matches instead.

Even just having this refuge can be a huge comfort. According to a 2011 USGAO report to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, shame, fear, and personal embarrassment are among the greatest barriers to ex-soldiers seeking counseling or treatment. Having a place where they feel understood and don’t have to explain themselves can help relieve some of these burdens and offer reassurance that mental illness isn’t something to be ashamed of.

“We open our doors to them and make it known their military family is still available to them even after they’ve left the service,” Williams explained. “Just being around and able to come game with other like-minded individuals and not have to be judged by people who don’t necessarily understand what you’ve been through, I think that in itself is a way for them to treat their individual injuries.”

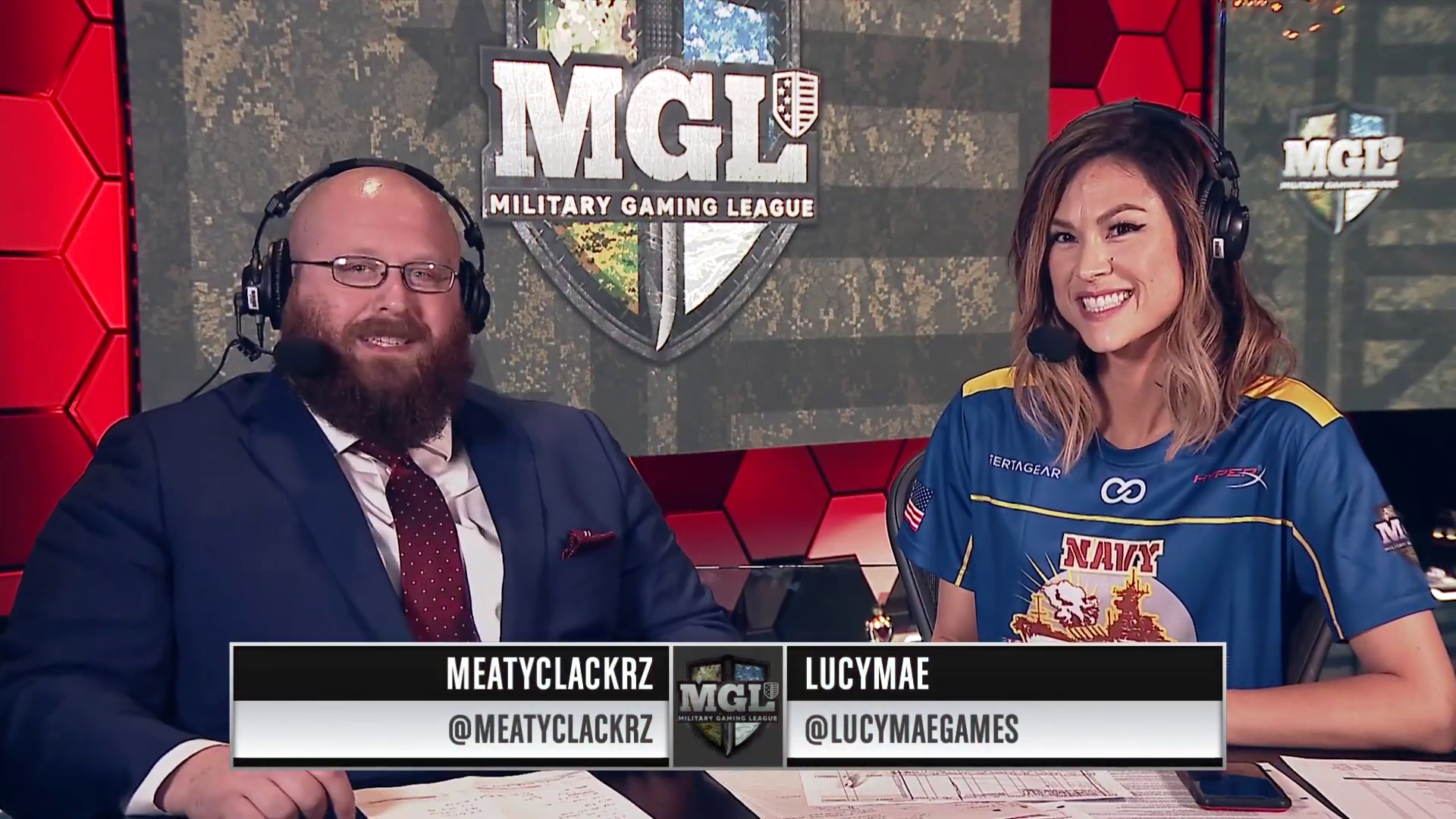

This isn’t to say the “league” part of its name is just for show. This spring, MGL ran its first major LAN event, a PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds tournament in Las Vegas, involving a massive stage setup, almost 60 competitors, sponsorship, and an official broadcast. The competition saw the top five duos teams from the Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marines, and Navy all vying for the top prize in an evening-long skirmish. Esports and streaming personalities—including Twitch partner and Rogue streamer Kat Contii, host and shoutcaster Lucy Mae, and Ghost Gaming’s Kevin “Miccoy” Linn—were in attendance, further legitimizing MGL’s efforts.

values on par with other major esports events.

Credit: Military Gaming League

“A lot of entities want to support what we’re doing,” Williams said. “We did this PUBG event, we’ve done stuff with Ubisoft before. I think people understand it’s a really good way to give back to service members and veterans that are in the gaming space. Sometimes it might seem like there’s not a lot certain people can do to help out veterans. In the gaming world, I think they’re realizing MGL is a really good avenue to help out.”

Military Gaming League has worked in concert with other groups—including U.S. Army Esports, which was created in September 2018. Unlike MGL, Army Esports is part of the Department of Defense and only open to active service members, who can try out on a rolling basis to compete in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, Rainbow Six Siege, Overwatch, and League of Legends. Bringing together people from the military and reserves stationed all around the world, the venture is an attempt to better showcase the lives of those in service.

“Every time I engaged with somebody that had no previous information about the Army, they didn’t realize that the majority of us still had the exact same hobbies as they did,” said Sergeant First Class Christopher Jones, co-founder of U.S. Army Esports. “The conversation started as ‘Oh, you’re a paratrooper,’ and all these other things, and I said, ‘Well, yeah, I’m that, but my passions are gaming and watching anime and these other things,’ and the more that happened, I started to notice that we might need to actually push this out.”

Army Esports sits at the intersection between advertising the military and humanizing it. On the one hand, it exists because it might persuade members of the American gaming public to become soldiers. On the other, it reminds us that service members aren’t completely defined by their life in the field. Traveling with his Xbox, Playstation 2, and Nintendo Gamecube while stationed overseas—not an unusual sight on an army base, he pointed out—Jones wanted to help people understand that military life and gaming weren’t mutually exclusive. A Street Fighter V tournament was put together with the help of MGL and streamed on Twitch, featuring SFC Jones co-commentating, that acted as a proof of concept. That concept has since expanded into a proper organization, through which the active duty and reserves can advertise their skills and love of games to the masses.

Of the four teams currently competing, the Counter-Strike and League of Legends squads have seen the most action, taking on American universities in friendly skirmishes as they solidify their lineups, turning a few heads with their comparative skills. “A lot of people in the industry who’ve seen them compete or watch them play have told me there’s a lot of potential here,” Jones asserted. “A lot of them have no previous professional experience. All the way down to the fighting games, we had one of our guys compete in the Northwest Majors [a fighting game tournament with a large prize pool held annually in Seattle], and a lot of the professional players are starting to watch these young soldiers who, before this, would’ve never been seen.”

Credit: Ubisoft

As nice as that positive spotlight is, there’s still an elephant in the room: that this is all a marketing gimmick to boost flailing recruitment stats. Army representatives have appeared on major networks talking about wanting to entice gamers into joining the ranks. This may be a great opportunity for soldiers and reservists to explore their hobby, and to help develop a better kinship between civilians and the military, but it’s also an elaborate PR move.

It’s not the first of its kind, either. Since the early 2000s the United States Army has developed and published America’s Army, a series of free first-person shooters that let players explore army life as a recruitment tool, all the way from boot camp through to active combat. The first three titles—released in 2002, 2003, and 2008, respectively—received positive coverage from the gaming and mainstream press alike, but some observers questioned the ethical implications. Gaming academic Dr. Nina Huntemann called the use of tax-payer money for the project “frightening.” Military journalist Nick Turse considered the games “only the tip of the military’s video iceberg,” taking the opportunity to collate other, often overlooked instances of the government stepping into entertainment aimed at young people.

After numbers of prospective soldiers dipped in 2005, the Army debuted a (very mid-2000s) advertising campaign featuring America’s Army. In 2008, it doubled-down on targeting children and teenagers by sending the most recent installment to schools. Though the series’ profile has waned somewhat, August of last year saw the announcement of a new America’s Army game, tentatively scheduled for release in 2021.

Credit: U.S. Army

The role of U.S. Army Esports within this broader tradition makes it easy for skeptics to write off as a simple propaganda tool. It’s hard to imagine the initiative existing if it couldn’t provide the Army with more than heightened morale. Jones was careful in his response when asked about criticism of Army Esports being used for recruitment: “We just want to start the conversation. We are an all-volunteer army; no one has to join. Only 30 percent of our population’s even qualified. At the same time, we can start that conversation, and even if you don’t enlist in the United States Army, we can still play games together.”

In large part, MGL’s Williams believes, it’s about altering perceptions. “There’s a certain stigma sometimes between civilians and the military. The civilians don’t really understand what the military does besides what they see on TV and in the news. There’s a deeper meaning to what the military does and so many other jobs and things you can do,” he said.

These answers beget bigger questions, such as whether defense forces should be advertising at all, and what forms are ethical for those ads to take. But it would be misleading to view these esports initiatives as only recruitment drives. The Military Gaming League is providing support to people who badly need it, and Army Esports is creating extracurricular structure that may very well be a literal lifesaver for those stuck in troubling circumstances on active duty. At a time when veteran services are often lacking and the mental health issues service members face are only becoming more multitudinous, these programs have the chance to serve as vital sanctuaries.

No matter how many difficult questions remain, the ties between the U.S. armed forces and gaming are unlikely to weaken in the years to come, and not just because of recruitment. According to Williams, there’s another major factor behind this convergence: the future of warfare itself. “There’s so many skills that gamers have that could help in the military, and vice versa. The military’s becoming more technologically advanced, and the people that are going to be good at working these new systems and these digital battlegrounds are going to be gamers.”

Header image: Ismail Seghier for EGM.

Anthony is a freelance writer and dream warrior published in PCGamer, PCGamesN, GamesMaster, Digital Trends and Variety among many others. He enjoys comics, professional wrestling and buying band merchandise as a form of self-care. His favorite games include Hollow Knight, Gorogoa and Brutal Legend, and he believes ‘Divine Intervention’ is Slayer’s best album and there’s nothing you can do about it. Tweet him horror movie recommendations at @AntoMcG.