“To create a space that is other […] as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled.”

Michel Foucault

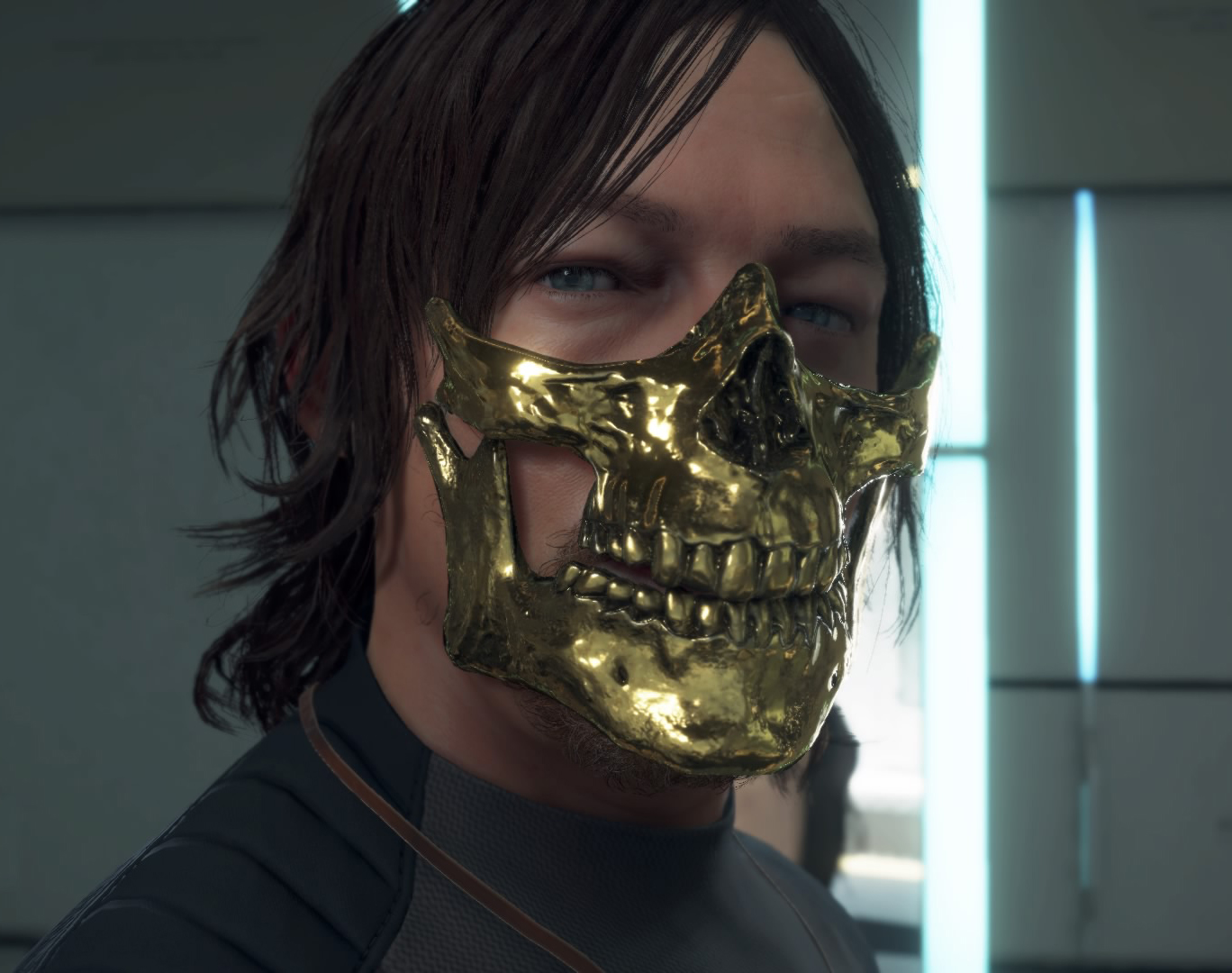

Sam Porter Bridges looks at his reflection in the mirror. He washes his tired face. He fools around with a new hat, trying to forget about the events happening outside the room for a moment. Then, unexpectedly, a flash of light emerges. The man in the golden mask appears right behind him—but nobody’s there when he turns around. Seconds later, the camera reveals that Sam’s the one wearing the mask now. A quick transition puts him out of the trance and back to his bunk bed, any glimmer of hope or security introduced by those four walls reduced to a mere dream.

I came to adore the private rooms in Death Stranding during my extensive and tiresome 96 hours with the game. These safe environments provide shelter and a bed to sleep on after a long day reconstructing an online network throughout a decaying depiction of the United States. Regardless of how muddy your boots are or the amount of blood on your suit, everything can be washed away with a shower—or almost everything.

It might be due to the exhaustion or simply the constant torment of his journey through paranormal vistas, but Sam’s mind quickly begins to materialize his worst fears. This hostility tears down the walls of otherwise monotonous visits to these protected spaces. Lingering horrors show up to spoil his brief respite, acting as illusions that might as well be nightmares come to life, recreating the dangers he witnesses in the wilderness. It might be a safe room by definition, but our perception of it as such becomes compromised.

Credit: Sony Interactive Entertainment

Over time, I started to feel dread during these moments of rest. BB, the baby inside the pod that you carry throughout most of the game, is probably Death Stranding’s most harmless character. Yet, in another surreal sequence, you can see him punching the glass case—at first a game that Sam gladly plays with BB, but one that devolves into an aggressive outburst. The baby bashes harder and harder against his glass prison, first with his tiny fists, and then with his head, until he finally manages to break through. Witnessing that moment, I was as terrified as Sam.

Death Stranding lures you into these supposedly safe environments only to subvert them into sources of fear afterwards, setting traps in the most mundane actions to showcase that nowhere is truly safe. The game’s unexpected cutscenes made me think about the way video games have introduced safe rooms over the years, serving as stationary checkpoints to replenish oneself and plan ahead without worrying about a sudden attack—and how some have started to break the promise of immunity, both physically and psychologically, from the inside.

In an interview with PC Gamer, the director of the Resident Evil 2 remake, Kazunori Kadoi, reflected on the purpose of safe rooms in games, especially those within the horror genre: “We thought that having nothing but tension throughout the whole game would be exhausting for players, so we designed the save rooms as a safe place to take a breather from the horror.”

As Gloomwood developer Dillon Rogers expressed during a 2018 interview, these spaces thrive in providing emotional releases. “A large part of the drama of safe rooms is the hope they represent. The context that the player may actually survive this nightmare,” he explained.

Providing players with relief and respite has been the main role of safe rooms throughout the years regardless of the genre. It’s natural for players to trust these save points as secure places, as one would never expect enemies to disrupt them—the Santa Monica flat in Vampire: The Masquerade, for example, feels like home after a couple of visits. Likewise, camping in Darkest Dungeon can help your party to forget about the eldritch horrors imprinted on their shackled minds. But there’s a risk of being ambushed during your sleep, triggering a combat encounter where your party is at a disadvantage, deprived of light. All previous efforts to calm and cure them are put in jeopardy. Careful strategizing can only decrease the chances these ambushes occur, not prevent them altogether. There’s one character in particular, The Shieldbreaker, who can trap her teammates in an illusion during the night, giant vipers manifesting themselves as the group struggles to fight in the desert, far away from their tents.

Credit: Red Hook Studios

Kadoi, the Resident Evil 2 director, also reflected on why it wouldn’t be fair to change their purpose, at least in Capcom’s survival horror series: “I don’t think we should ever break the rules as far as letting the player be attacked and hurt in the safe room. We’re supposed to establish rules by which you play and complete the game, and it would be unfair to break them like that just for the sake of a twist.”

To some extent, that’s exactly what happens in the Raccoon Police Department. Protagonist Leon Kennedy finds lieutenant Marvin Branagh in the last few moments before the infection running through his veins completely takes control over him. During this first act, Leon begins to explore the station and its whereabouts. While there are other safe rooms that slowly reveal themselves the further he ventures into the building, this main hall serves as the first save point in the game, while simultaneously acting as the heart of the police department to which all the branching hallways will eventually lead you back. But at one point, the lieutenant can fight no longer. He becomes one of the many undead creatures roaming the station, menacing the starting area he once guarded. From that moment, lifting up your gun before entering the hall becomes mandatory. Anything can be waiting for you behind that door.

Credit: Capcom

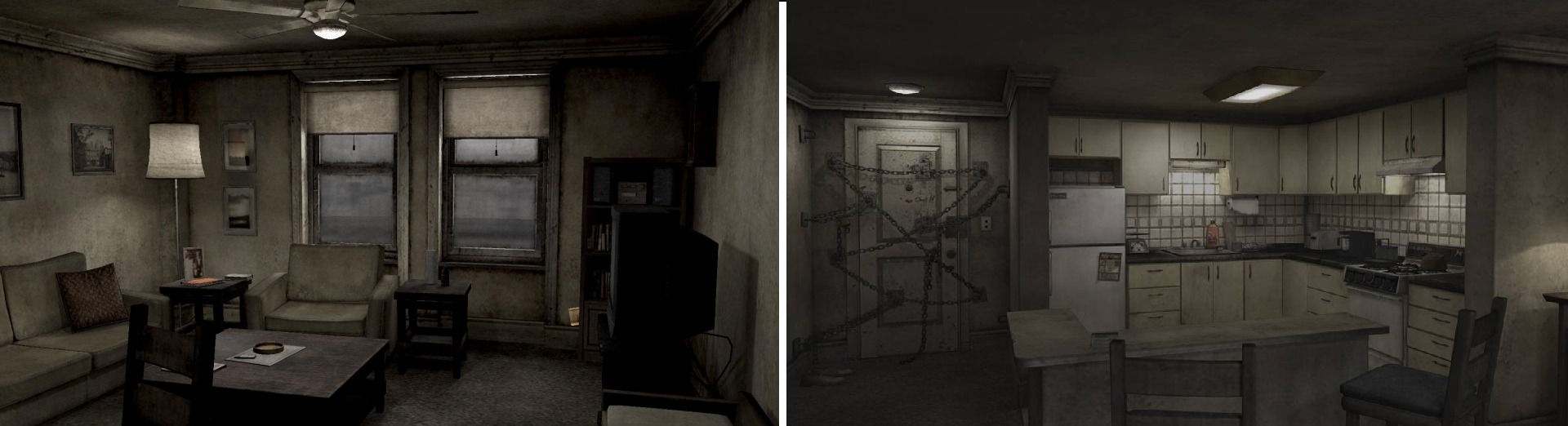

Silent Hill 4: The Room masterfully played with the concept of unsafe rooms back in 2004. Room 302 has an equal importance with protagonist Henry Townshend, serving as both the starting point of the story and a recurrent, evershifting space.

Imagine waking up in your apartment after living there for two years, only to find out that the door is locked. In the most unimaginable scenario possible, this comes from the inside—several chains and padlocks prevent you from stepping outside and resuming your routine. The fisheye peephole lets you see people from time to time, but no one seems to hear your calls for help, no matter how loud you scream and kick the door. This previously safe space is now a prison cell.

Henry is only able to exit through a hole in the bathroom, which grows bigger and bigger, but he eventually needs to return. This isn’t just so the story can progress, but also so that you can save your progress: You can only do so inside of room 302. It is, by definition, a safe room. But there’s nothing harmless about it. Over time, it begins to come to life in the worst possible ways. There’s a thin line between the psychological and the physical here, as Henry will start seeing eerie transformations of everyday objects, along with the presence of hauntings that decrease his health. Most importantly, these visions start to inhabit his home, or what’s left of it, as physical entities. Visitors show up even when the door is tightly closed from the inside, and the only way out guarantees similar (or even worse) fears.

Credit: Konami

Silent Hill 4 rips apart any semblance of safety piece by piece, and distrusting even the most mundane actions becomes the norm. The air feels heavy. Your shoes are misplaced. There’s a putrid smell coming from the fridge. The TV keeps flickering, the figure of a man upside down blurring itself behind the static. The shadow of a child now lives in the closet, and you can only hear their sorrow. The couch where you used to read or fall asleep now has blood all over it. In the most vicious moments, Henry can see a reflection of himself on the other side of the peephole, portrayed as a living corpse—a mirror of his current state, the apartment draining what’s left of his humanity, using his life force to make these nightmares stronger.

In all these examples, safe rooms share many similarities. Their purpose is to give players a breather, a chance to refocus or realize how physically battered they are. But when their transitory nature is twisted even further, giving these places a personal hook either through the plot or the emergent stories created during recurrent visits, it’s easy to fall into the trap created by the illusion of solace with a quiet room, words of encouragement from a friend, or the warm touch of a bonfire. Safe rooms can be great narrative spaces with accumulated value, but it’s the thought of encountering a threat inside that makes them so frightening. It has happened before, and nothing can prevent it from happening again.

Subverting expectations isn’t new in media, especially when it comes to horror. But toying with an element that might as well be considered tradition at this point, a place where the player is supposed to be able to let rest, is completely different. Disrupting the expectations of safe rooms compromises your perception not only in the game you’re playing, but beyond it as well. You’ll begin to fear mundane interactions that aren’t supposed to change. The initial glimmer of hope from locking down a door becomes pointless when danger could come from the inside. Candles and medallions become necessary to protect yourself from the hauntings inside your apartment, or your life will slowly be swept away from you. Now, the thought of returning home sends a shiver down your spine.

Next time you step into a safe room, think twice about immediately relaxing your muscles and taking that long awaited deep breath. Memorize every nook and cranny, as they might not be in the same place during your next visit. Plan an escape route, and don’t be fooled into thinking that this place only belongs to you.

Be extra careful when looking at your reflection in the mirror—you might notice there’s someone else trapped inside those walls.

Header image: Konami

Freelance journalist from Argentina. Frustrated bassist. Learned English thanks to video games. He runs Into The Spine, a site that hosts stories around games and what they leave behind, along with supporting both upcoming and established writers. He’s probably listening to music right now, or procrastinating on Twitter.