Bards have been a constant source of amusement in video games for decades. Whether they’re accompanying a Witcher on a quest to locate a monster or simply stringing together a tune in their local tavern, their enjoyment stems primarily from offering players a nonviolent way of interacting in worlds often shaped and defined by violence. Across video games they can fulfil a number of roles, from boosting the morale of your party to introducing romantic subplots to serving as historians or community figures. But the bardic tradition goes back much further than you might expect.

Originally, the title of “bard” was used to describe Celtic tribal singers from Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, who would perform eulogies and satires for rich patrons with the use of instruments such as the harp or the crwth. A common theme of their songs was the inhospitality or failure of the rich to pay debts, as well as tales of heroic deeds, religious ballads, and songs of adulation or praise for their benefactors. Over time, however, the term has been broadened significantly to include a number of similar cultural traditions, including the Southern European minstrel and the Norse skald.

Credit: Bethesda Softworks

First introduced in The Strategic Review Volume 2, Number 1, the bardic class in Dungeons & Dragons functions as a “jack-of-all-trades” and borrows aspects from this same multitude of traditions. It usually occupies a supporting role in an adventuring party, allowing the player to use songs in order to cast spells and inspire others. This balanced approach means players can roleplay and resolve conflicts through methods other than violence, such as charm and suggestion, letting you take a more charismatic and social approach to the game.

The association of the bard with spells and magic is one that likely stems from legend and their close proximity to the druids. The Welsh chronicler Elis Gruffydd, for example, wrote of a Welsh bard named Taliesin, who was said to possess the ability to predict the future. However, the perception of the bard as a magician was likely fermented in the public’s imagination with the arrival of the Pre-Romantic and Romantic poets, such as Thomas Gray, Felicia Hemans, and William Blake, who drew not only on the bard as a performer and keeper of lore but also as a prophet and seer. You can see this within Gray’s “The Bard: A Pindaric Ode,” as the titular bard curses King Edward I of England and his conquest of Wales from the heights of Snowdon: “Ruin Seize thee, ruthless king!” Shortly after, the bard follows up with another prophetic act, a premonition of ruin for both parties: “The different doom our Fates assign. Be thine Despair, and scept’red Care, / To triumph, and to die, are mine.”

Credit: inXile Entertainment, Krome Studios

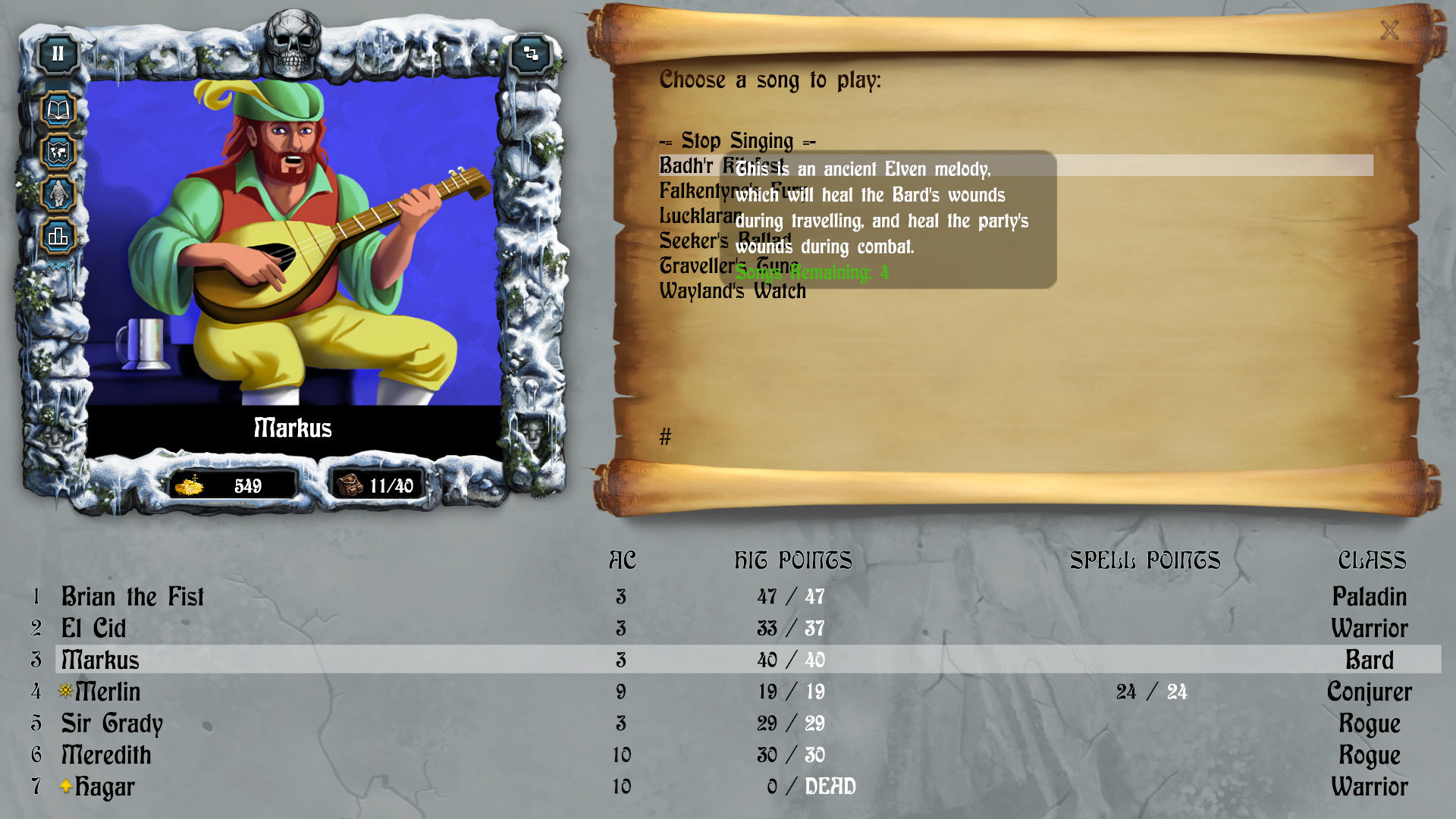

As generations of game developers huddled over their computers in the hopes of translating the experience of Dungeons & Dragons into code, the bard quickly established itself as a staple of class-based role-playing games, again offering an alternative to more traditional hero classes. The Bard’s Tale, for instance, not only features a bard as its narrator, but also allows players to recruit bards into their parties to heal allies, cast protection spells, and soothe angry monsters in battle—an addition that introduces variety to the combat. Likewise, the Final Fantasy series has also included the bardic class across several of its games, giving players the ability to sing and cheer their allies in battle, as well as scare off enemies, and temporarily hide from attacks. In both these cases, the bard expands the vocabulary of combat beyond violence, flipping the system on its head. Much like their association with magic, this portrayal also has a historical basis, calling to mind the performance of the Irish Ollamhain Re-dan or Filidhe poets who would lead their armies into war with music before watching passively from a distance.

Credit: Square Enix

With Final Fantasy IV, Square momentarily abandoned this class-based approach, instead designating the role of bard to a single character, Prince Edward. Edward inherits many of the same traits of his predecessors, but also takes advantage of the bard’s romantic potential, likely for dramatic effect. Much like Orpheus, the “Thracian bard” whose wife, Eurydice, was killed shortly after her wedding day, Edward’s beloved Anna is murdered early in the game when the Red Wings bomb the kingdom of Damcyan. The bard’s heartbreak is what motivates his journey, as he is haunted by the ghost of his dearly departed. But unlike Anna’s father—Tellah, the fiery and confident sage—Edward is plagued by doubts and isn’t necessarily seeking revenge. Instead, he simply wants to find peace for those he has lost by helping the rest of his party defeat the evil sorcerer Golbez. This is what makes him such a fascinating character to have in your party. He isn’t your typical hero, acting as a contrast to the rest of the group.

Greg Lobanov’s 2018 game Wandersong takes this concept even further, capitalizing on the bard’s potential for innovative game design. Here you play as a character who uses their ability to sing to solve puzzles and resolve conflicts. You do this by navigating a wheel of musical notes and inputting patterns or performing in time with onscreen prompts. The game communicates this approach succinctly in its opening scene, where the bard picks up a sword, only to be quickly disarmed. This communicates to the player that this won’t be your typical action-platformer or even your bog-standard hero, with the bard abhorring violence in favor of other methods, such as communicating with monsters, curing creatures, and reuniting lost souls. It’s an approach that feels genuinely refreshing, constantly subverting our expectations of the genre within boss fights and other confrontations.

Credit: CD Projekt RED

Perhaps the most notable bard in all of gaming is The Witcher’s Dandelion. (In the popular Netflix series, he’s known by his original Polish name, Jaskier, a reference to the flower commonly known as “buttercup” in English.) Dandelion acts as a foil to the sarcastic monster slayer Geralt and is depicted as a philanderer whose carnal appetites and impulsive actions never fail to land him or his friends in trouble. This is something you can observe in the quest “Broken Flowers” in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, as Geralt must visit a number of women who had encountered Dandelion prior to his disappearance to find out the bard’s whereabouts.

Dandelion is a much bawdier depiction of the bard, yet in spite of this he proves himself a dependable ally and an invaluable resource at times, helping Geralt to resolve some of his more complex contracts peacefully. Such as in the case of the first Witcher game, when Geralt uses Dandelion’s poetry to put the soul of a murdered bride to rest, or in The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings, when he is dragged along to seduce a succubus accused of killing soldiers in order to find out her side of the story. His relationship with Geralt is a delicate give and take, with the bard able to squeeze some stories out of his adventures with the Witcher in exchange for acting as bait.

Of course, bards also appear more generally within role-playing games, usually as NPCs populating cities and towns. As an example, in the first two Fable games, players can employ a bard to sing about their heroic deeds and spread their renown among their fellow townsfolk. This is an activity that feels in keeping with the series’ fascination with heroes and speaks to the perception of the bard as a pillar of the community. In the third game, this feature was removed, however, and replaced with a more entrepreneurial approach: Players can pick up the lute themselves to earn some extra gold in a Guitar Hero–like rhythm game.

In The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, bards are also a common sight, performing in the damp and dreary taverns of Tamriel or studying in the prestigious bard’s college in Solitude. What distinguishes them from other NPCs in the game is that you can request for them to play songs to teach you about Tamriel’s history. These include pieces such as “The Dragonborn Comes,” “Ragnar the Red,” “The Age of Aggression,” and “The Age of Oppression.” In The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, bards are not only a form of entertainment, but also the local historians and the voice of the people. Depending on where you are in the world, for example, you can encounter bards who are singing either pro-Stormcloak or pro-Imperial songs, with their music detailing the conflict and the mood in the neighboring area.

More recently, we’ve even seen bards make appearances in games where they don’t necessarily exist, at least not officially. In Mordhau, players have taken advantage of the in-game lute to create their own builds, momentarily stopping the violence with performances of popular songs. This has become such a popular trend that killing bards in the game is generally frowned upon, with both sides usually choosing to leave them be or risk being labelled a “bard killer.”

Credit: Triternion, via Reddit user _magicm_n_

The bard has been a persistent figure in popular culture for centuries. An amalgamation of different traditions, it has come to represent both an ideal and an alternative to the traditional fantasy hero. In video games, bards have appeared as both playable characters and as NPCs, where they can provide refreshingly non-violent ways of interacting within the world. Though they are undoubtedly a fairly stock character, there is still variety in how they have been portrayed, with creators trading on their classical associations to create complex and emotionally compelling characters as well as amusing departures from the status quo. In a medium dominated by sword-wielding heroes and tough-guy protagonists, it’s fun to pick up an instrument and let loose once in a while. Or take a break from fighting to enjoy a show in a quiet corner of the world.

Header image credit: CD Projekt RED

A freelance journalist and lapsed musician from Manchester, U.K., Jack Yarwood spends most of his time playing Sea of Thieves online and the rest of his time tweeting about his obsession over on Twitter. Apart from writing, he’s also started branching out into video, making short films on the U.K. initiative Girls Game Lab and indie development in his home city. He has a particular interest in gaming communities and deep dives into game design.