Hieronymus Bosch’s famed triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights houses divine secrets. Unveiling a strange paradise of desires and foreboding creatures, its populace whispers and glare at each other as if aware they’re being watched. Heaven. Hell. The whimsical decadence that connects the two realms.

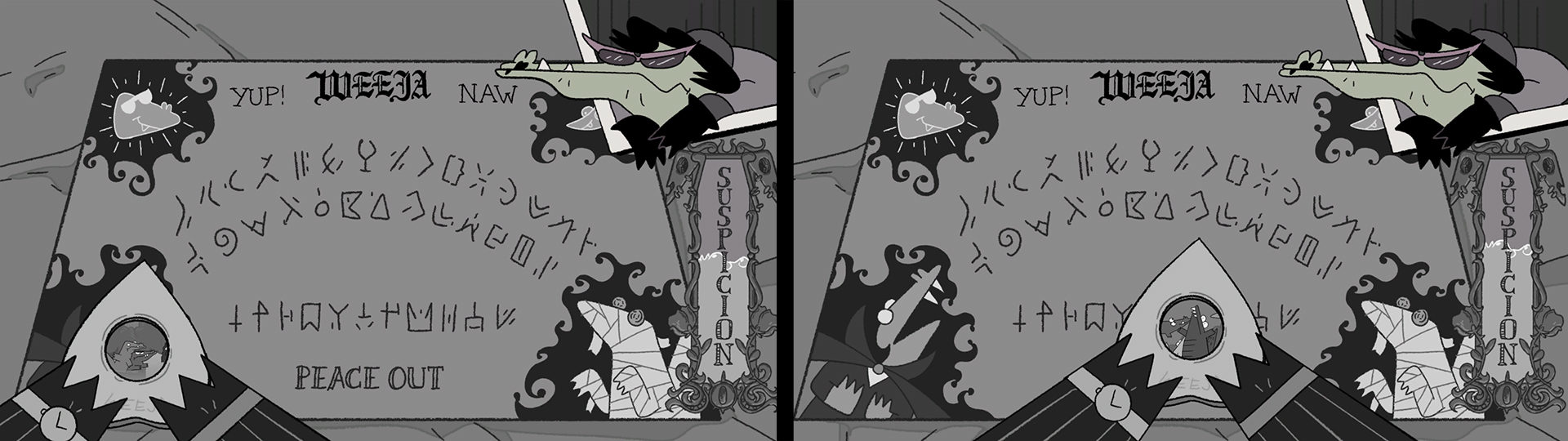

Lindsay and Alex Small-Butera recreate the 500-year-old Dutch painting in their new game, Later Alligator, but replaced all the “scary hell stuff” with jolly cartoon gators. The haunting wispy humanoids swapped for googly-eyed, fun-loving green sweeties. As part of a seance sequence, a planchette is held across a board to chase a tiny ghost, revealing glimpses of the Bosch spoof from the spirit world. It was only after going all-in on the tapestry that the Small-Buteras realized the joke might not land if you can only see it one planchette peephole at a time.

It was a pain in the tail to program too.

“The original concept was so simple,” Pillow Fight producer Jo Kreyling said in an email. “We were continuously unhappy with it, drawing more, coding more. We iterated on the concept a ton and lost probably a whole week.”

Credit: Smallbu, Pillow Fight

Lindsay and Alex Small-Butera, known as Smallbu, are long-time animators, nabbing an Emmy for their work on Adventure Time but best known for their viral Baman Piderman toons. As Pillow Fight, Jo and Conrad Kreyling have published visual novels such as We Know the Devil and Heaven Will Be Mine, each emphasizing their artwork but not fully animated.

When the two decided to collaborate, fusing their skills as animators and game makers, they made a motto to keep things simple. The motto backfired throughout the game’s development, as we discussed during a talk at the Toronto Comics Arts Festival, over email, and in a crowded glass elevator where we appropriately shared a lack of enthusiasm for heights.

Pat the alligator never asked for trouble. Anxiety-wrecked and decked out in a red neckerchief, Pat suspects that his yammering has gotten him into hot water with the larger alligator family. The kind of family who don’t take too kindly to yammering. You take to the streets of Alligator New York City, meeting with affiliated family members, playing their minigames, and trying to deduce just what’s in store for poor ol’ Pat.

The city is something of an anachronistic space, with flip phones cohabiting with barbershop quartets and trolley cars. The city looks informed by ragtime ’80s family restaurants, but more animated than the clockwork tiltings of any Rock-afire Explosion. Alex Small-Butera’s family is from Long Island, and the region’s inherent tackiness fed into the game’s direction.

“One of the biggest inspirations for the look of the game was a cache of pictures taken of the interiors of old, ornate homes from the ’50s and ’70s,” Lindsay Small-Butera said. “Have you ever been to Long Island? It’s like being in a fever dream. It’s all kitsch, it’s pretty wild.”

While Lindsay cites Professor Layton as one of her favorite games, the movement of Alligator New York City draws from Smallbu’s animation traditions more than games are usually granted. From the lounging lizards of the park to busybodies zipping up and down the antique store staircase, the backgrounds are less typical idle animations and more like vertical slices of a cartoon. Add on pop-up surprises when you click around the environment, a la Freddi Fish, and the final game has somewhere in the ballpark of 40,000 frames. Unfortunately, you can’t just draw a video game and hope for the best.

The Small-Buteras met the Kreylings at Conrad’s birthday, back when he was living with some of Lindsay and Alex’s chums in (regular human) New York City. The idea of making a game was floated by team Smallbu soon after. Plans loosely bounced between the two animators until the idea of Later Alligator got stuck in Lindsay’s head. Smallbu approached Pillow Fight games with their dark comedy about dark green reptile folks.

“When I’m thinking about investing in a pitch, usually I look at the track record of the creator,” Jo Kreyling said. “Do they make things that make people gasp? Is it original, and interesting, and does it have appeal for an audience shopping for something new?” As different as Later Alligator looks from the rest of the Pillow Fight catalogue, these qualities made the project a fit for Jo.

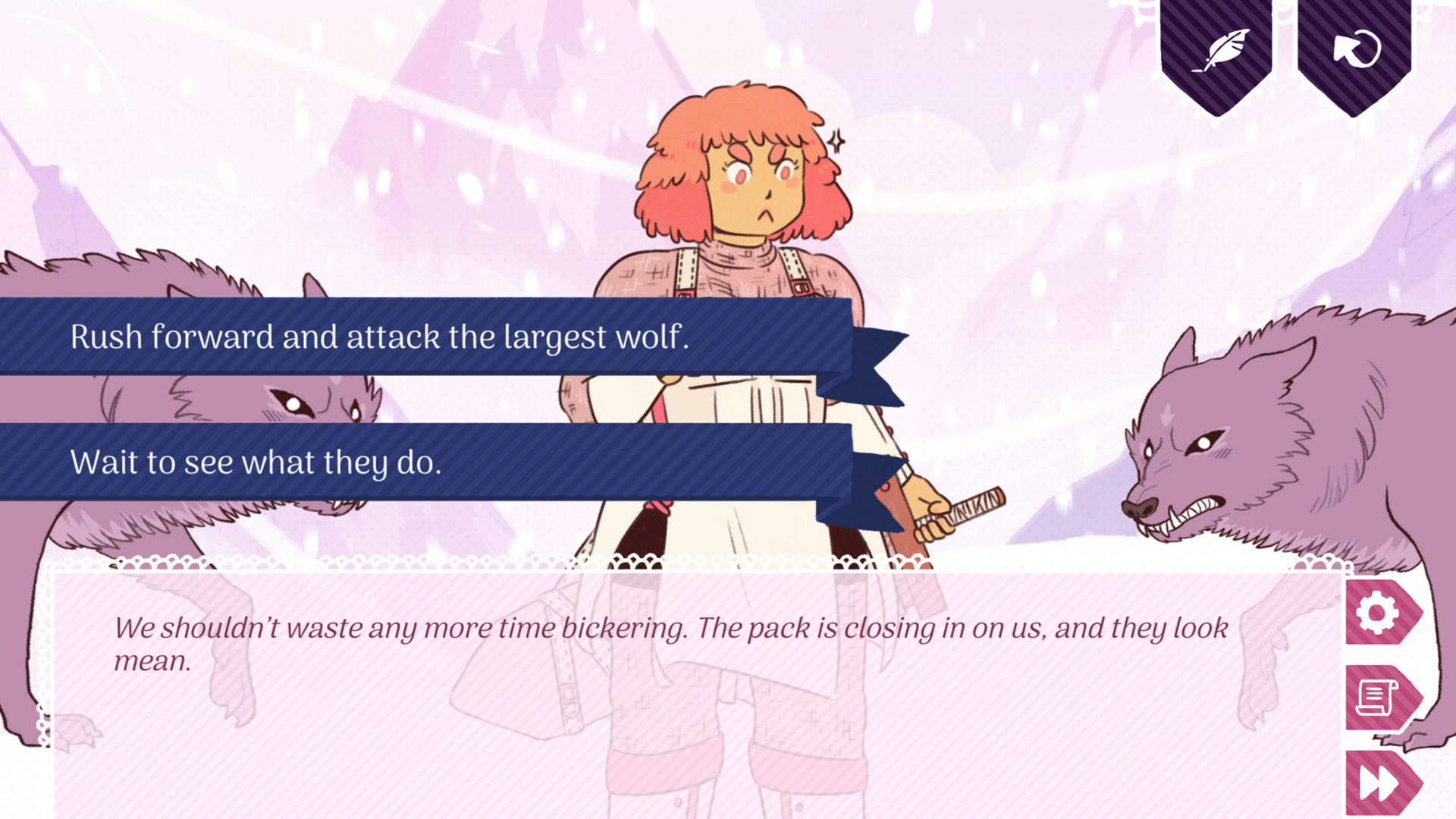

Fully animated games were never the end goal for Jo Kreyling, but she did fess some envy over cutscenes found in Japan’s visual novels. “We wouldn’t have built a game like this without [Smallbu’s] vision driving it,” Jo Kreyling said. Pillow Fight’s games, like many visual novels, have dating elements to them but Lindsay felt that sleuthing alligator pals was a more natural fit. “I can’t make a romance game because I’m shy,” she said.

“At the beginning of the design process, we drew amazing sketches for each other to describe actions and how things should look,” Jo Kreyling said. “We prioritized which games would be hardest conceptually, and worked from both sides to describe what we thought would be a good gameplay experience. The animators would animate, and Pillow Fight would build a prototype, and we’d discuss, sometimes argue, about the best solution for each minigame. Sometimes, we were wrong! Some games were abandoned or redrawn, and sometimes we the devs had to get a little clever.”

Credit: Pillow Fight

Animation and games are, obviously, compatible fields. World-building and sequential thinking apply naturally to both. Writing for a game instead of a cartoon wasn’t any obstacle. Mostly. Lindsay said it felt weird to give the player control when her natural impulse is stay planted in the director’s chair. But the small team didn’t prepare their Toronto lecture about easier adaptations or the little quirks of game design.

One of the first big shocks to the system was the amount of space quality animation consumes. Jo Kreyling said that loading and memory usage is a problem in any game, but the amount of animation cycles cohabiting any single scene just kept eating and eating. Packaging individual PNGs, every asset in the game, became part of the solution towards optimization, but Kreyling said that the loading was tweaked up until launch.

“Making the game has taught us entirely new ways in which to export animation files,” Lindsay Small-Butera said, “of which we will probably not need again in the foreseeable future. Them’s the breaks on this dink of an earth!”

All the minigames were their own mini-nightmares. Like with the Ouija seance, they chose simple activities that they assumed could be programmed easily. Think crane machines and three-card monte. Some of the least suspecting minigames grew into the biggest headaches. They were especially ride-or-die about including a pinball machine (not that I, the guy writing a book about pinball, blame them). Conrad apparently talks at length about mid-century urban developer Robert Moses’ efforts to ban pinball in NYC. Getting a pinball cabinet into Later Alligator required experimenting in both 2D and 3D, and listening to enough flipper sound effects to be haunted by them.

“Most of what we wanted we managed hell or high water to find a way to cram it in,” Lindsay Small-Butera said, “severing perhaps a few years from my total life span. There were a few minigames that fell by the wayside just for time’s sake, or because they were incredibly annoying. So no one will probably miss that.”

Animation! Game making! Neither are easy! At all! Games like Cuphead, bringing to life rubber-hose era Fleischer cartoonery, have been a smash hit. Cuphead required nothing less than seven years, an international team of artists, and remortgaging a house. Smallbu and Pillow Fight didn’t go so far as to put their equity on the line, but bringing Later Alligator to life has landed them in dicey financial straits.

“I don’t think anyone should have to remortgage their home to make good or interesting art and the lack of funding of the arts in general in America is a greater problem,” Lindsay Small-Butera said. “It’s scary! I know there are options like Kickstarter to get these things off the ground from the beginning a little more effectively, but not everyone striking out to make a game has the brand recognition at first to attract enough support to crowdfund something.”

After crashing through the process, Lindsay said that she’d be hesitant to make another game. If she did she’d have a better idea of the kind of project she’d enjoy creating. A game that would allow her to focus on art assets, writing and directing alone: a “guided experience” or “an interactive storybook.” In the more immediate future Smallbu are putting together a feature-length film.

“To make something indie often is a labor of love that is near impossible,” Lindsay Small-Butera said, “and only comes to fruition because of the sheer will to make it happen of those making it. This often involves poverty, ridiculous hours, and health issues.”

Games are hardly the only difficult creative field. Diminishing returns on independent art seems to be a source of frustration for Lindsay. When she sees an “amazing YouTube video” clocking only 2,000 hits, she thinks of all the times these platforms fail to bring the good stuff to her attention. And that “society sucks.” She doesn’t know the solution to these issues, but she does hope fans are more proactive with engaging in what they like, even if it’s as simple as sharing it around.

Later Alligator’s five-person team wanted to make a smaller game with more modest features and it still proved to be mountainous work. Through dedication and “discovering deep wells of talent and patience for each other,” it hatched into something gorgeous.

A cute, nebbishy little alligator, born somewhere between heaven and hell.

Zack Kotzer is a former carny and current writer out of Toronto. His work has been published in The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, Motherboard, Polygon, Kill Screen, and a column in NOW Magazine. His first book, Keeping the Ball Alive, details the history of the only pinball factory to survive the ’90s. He collects Fido Dido merch.