Do you remember being born? Is there such a thing as a curse that can change your past? Can a closed door become an open door without actually opening?

Well, no. Obviously not. Those questions are absurd. Unless you’re watching Petscop.

When you’re watching Petscop, the very fact that these questions have been asked hints at a whole world of mystery—one that has kept a dedicated community of viewers hanging on every word, studying every frame, and piecing together what’s been treated as a giant, mystifying puzzle.

Something like Petscop couldn’t really have existed at any previous point in time. It’s a series of videos that, at first, appear to be just amateurish uploads of footage from an unreleased video game, complete with halting, unpracticed voiceovers by the player. It’s the kind of thing you might stumble across during a deep dive into YouTube, among the thousands of Let’s Plays and game analyses that get uploaded on a daily basis.

However, it doesn’t take long to realize that there’s something different about Petscop, and over the course of its 24 videos, it slowly turns into a surreal, haunting, and often unnerving journey, filled with themes of abuse, trauma, and obsession.

I notice you named your file “Strange situation.” Is that your name?

To say that Petscop isn’t a real game is… mostly accurate. Nobody ever tried to develop a PS1 game by that name, and all the creators, players and testers hinted at in the videos are entirely fictional.

But on Tony Domenico’s computer, there’s a file called “Petscop.exe.” Everything seen in the Petscop videos comes from that file.

Every aspect of Petscop—its programming, graphics, music, voiceovers, and recordings—was created by Domenico. He says it all started after he watched a talk called “Stop Drawing Dead Fish,” which discussed how computer-based art can be “alive” in ways that drawings and animations can’t.

Afterwards, he had a dream about a livestreamed “puppet show” that used a game engine. Dreams being what they are, Domenico has since forgotten the details, but the concept came up again during a conversation with a friend about possible “creepy” projects that they could work on.

“First he was talking about the idea of animating a Let’s Play by hand,” Domenico said. “Then, as we talked about it more, it became, ‘What if you actually made the game?’”

The more Domenico thought about it, the more he realized that he had ideas for what a game of that sort would be like.

His dream wasn’t the only influence. Domenico says that Petscop drew a lot of inspiration from creepypastas such as Ben Drowned, a story regularly shared around the internet about a bootleg copy of The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. While playing, the narrator experiences a series of strange events that at first seem to be minor bugs, but as they increase in scope and bleed into real life, he gradually realizes that the game may be haunted by its previous owner. Petscop also drew inspiration from Marble Hornets, a YouTube series that follows the aftermath of a low-budget movie shoot during which the filmmakers ran afoul of the supernatural creature Slender Man.

Domenico also noted that movies by surrealist filmmaker David Lynch had a huge impact on his work. “Inland Empire is probably the largest single influence,” he said. “You know, this whole thing of being trapped in a cursed film, you can make certain connections.”

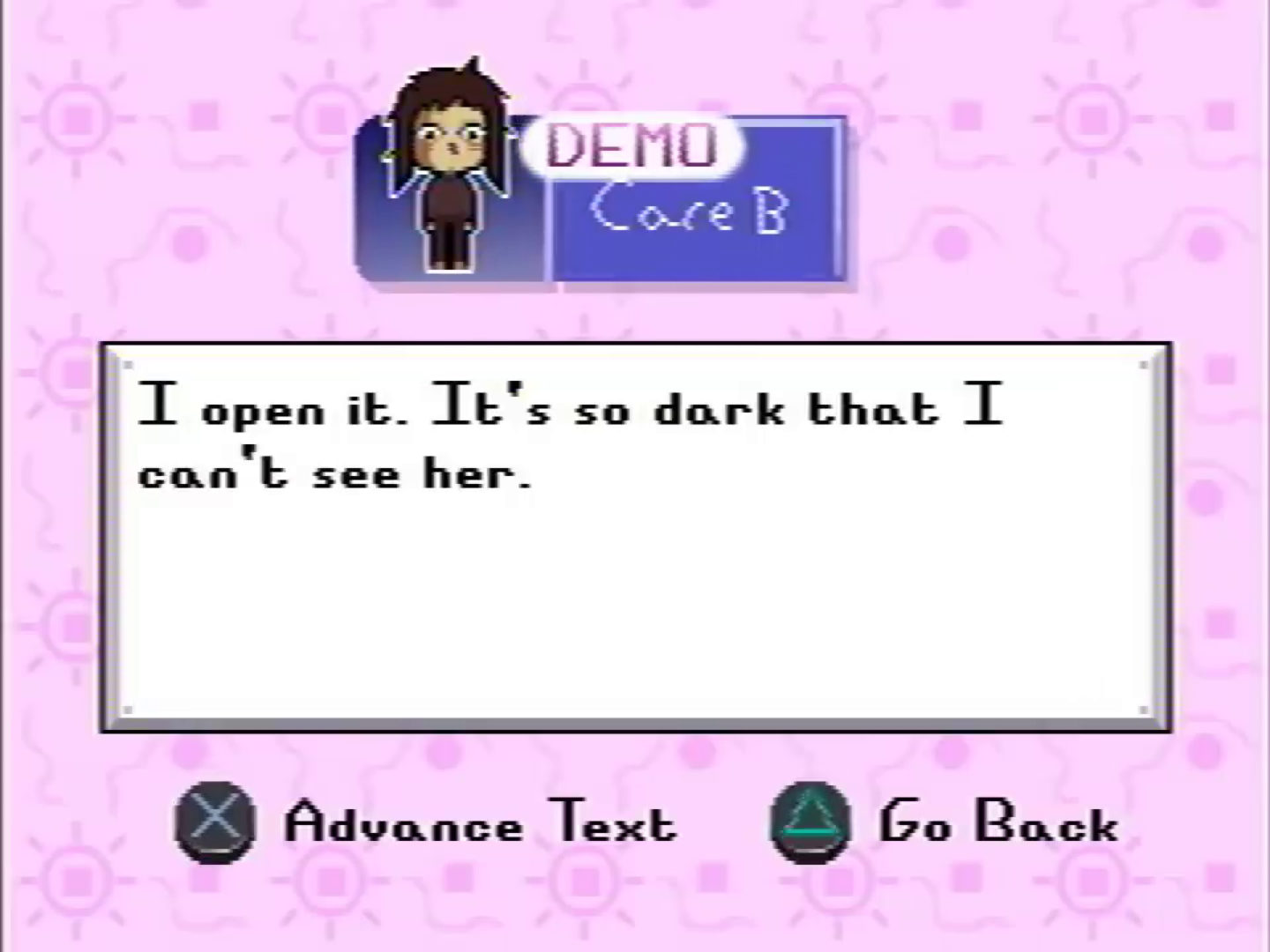

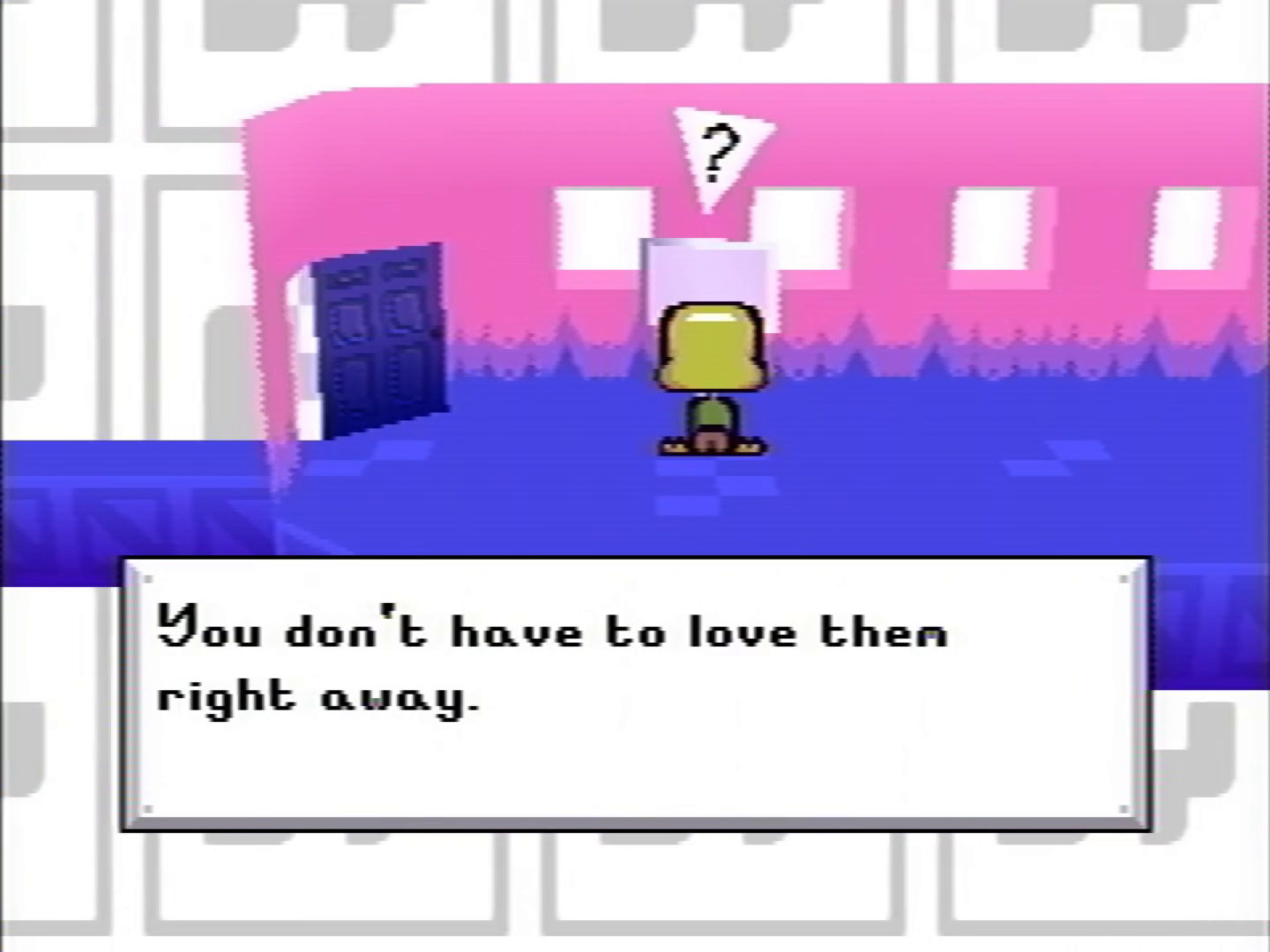

He also drew on some psychological experiments and therapeutic practices. For example, a clear reference is made to the “Strange Situation” procedure, which is used to observe the attachment between children and their caregivers. There’s also a scene that involves playing a board game with what appears to be a school counselor—a strategy that therapists sometimes use to analyze a young patient’s behavior.

“It was all stuff I read about years prior,” said Domenico. “I may have read about them further as I was starting, though I don’t remember now.”

On top of all that, he started working on the project because, well, it sounded kind of easy.

“I hadn’t finished anything substantial in a while and wanted something undaunting to get back into it,” Domenico said. “I guess it started as kind of a shallow thing.”

This actually is not the interesting part

Of course, the last word any Petscop fan would use to describe the series is “shallow.” That’s something that’s made clear in in the very first video, where you hear the nervous-sounding voice of the character Paul, who explains to an unnamed person why he’s uploading the videos.

“This is just to, uh, prove to you that I’m not lying about this game that I found,” he says. “I’m just gonna walk you through everything that I’ve seen so far, and uh… obviously it will be exactly as I described it, because this is it.”

In a normal Let’s Play, the style of dialogue would be a turn-off—an indication that Paul is nothing but a rote amateur who has no idea how to make a video interesting for his audience. But in the context of Petscop, it adds a thick layer of realism that sucks the viewer in. Most of us, if we tried to upload something to YouTube, would sound like Paul: stumbling over sentences, struggling to put into words exactly what’s on our minds.

It’s never outright explained who Paul is talking to, but there’s clearly a backstory between the two characters, with hints scattered throughout the series that are left for the viewer to piece together on their own. That’s how it goes with a lot of things in Petscop: Nothing is said explicitly, but there are plenty of breadcrumbs that imply something larger, and darker, at play.

“I like stuff that leaves a lot of room for the imagination,” Domenico said. “The way I thought about it was, I’m only showing a slice of things. I hoped to get across a feeling like there’s a lot more here, something strange and complex happening in the background, and you just aren’t getting a full view of it.”

What is shown—in the first video, at least—is footage of a strange, brightly-colored PlayStation 1 game about catching unusual pets inside an abandoned facility. Catching these pets requires the player to solve a number of puzzles, such as sliding a bucket under a living rain cloud or slipping into a cage after flipping a switch that slowly closes the gate.

The puzzles themselves are a little unusual, but they follow a sort of logic that a player could reasonably figure out given enough time to experiment.

If you pay enough attention, however, you’ll notice that something’s off about a number of little details. A sign laments that “we have failed to remove all of the Pets from their homes.” Another sign tells the player not to be discouraged if they run from you. A trophy calls one Pet “a real champ” for its refusal to leave its cage.

To make sense of this, Domenico said, you need to try to get into the mind of the fictional game’s developer.

“That beginning part of Petscop was still created by someone,” Domenico said. “That’s a really important thing. Everything is there because somebody decided to put it there. And so you can wonder, who was it, and what was their state of mind?”

Any unease caused by these strange elements are soon found to be justified by the end of the first video, where it’s revealed that the game contains an entire hidden world that dwarfs what’s on the surface.

It’s a massive, dark plane, holding mysteries and impossible puzzles that reveal a story about kidnappings, deaths, and an unknown group of conspirators that seems to be forcing Paul to keep publishing videos.

This is a little more than I was expecting to see

Petscop wasn’t shared to the public until after the first four videos were uploaded, and there was already a lot to digest in that first wave. It’s creepy, though not in the way that threatens anyone directly. It’s kind of a slow burn that strongly implies that there’s something horribly wrong. It’s a kind of horror that Domenico wishes there were more of.

“Every October I’m like, here’s that mood again, and I get kind of excited about it,” he said. “Then I remember that the majority is cheese, or pure misery, or torture, or all of the above. That is not my thing. The whole vibe repels me and makes me feel kind of sick.”

“So it’s like, anything can happen. People could jump out of your TV, that kind of thing. I love trying to bring myself back to that.”

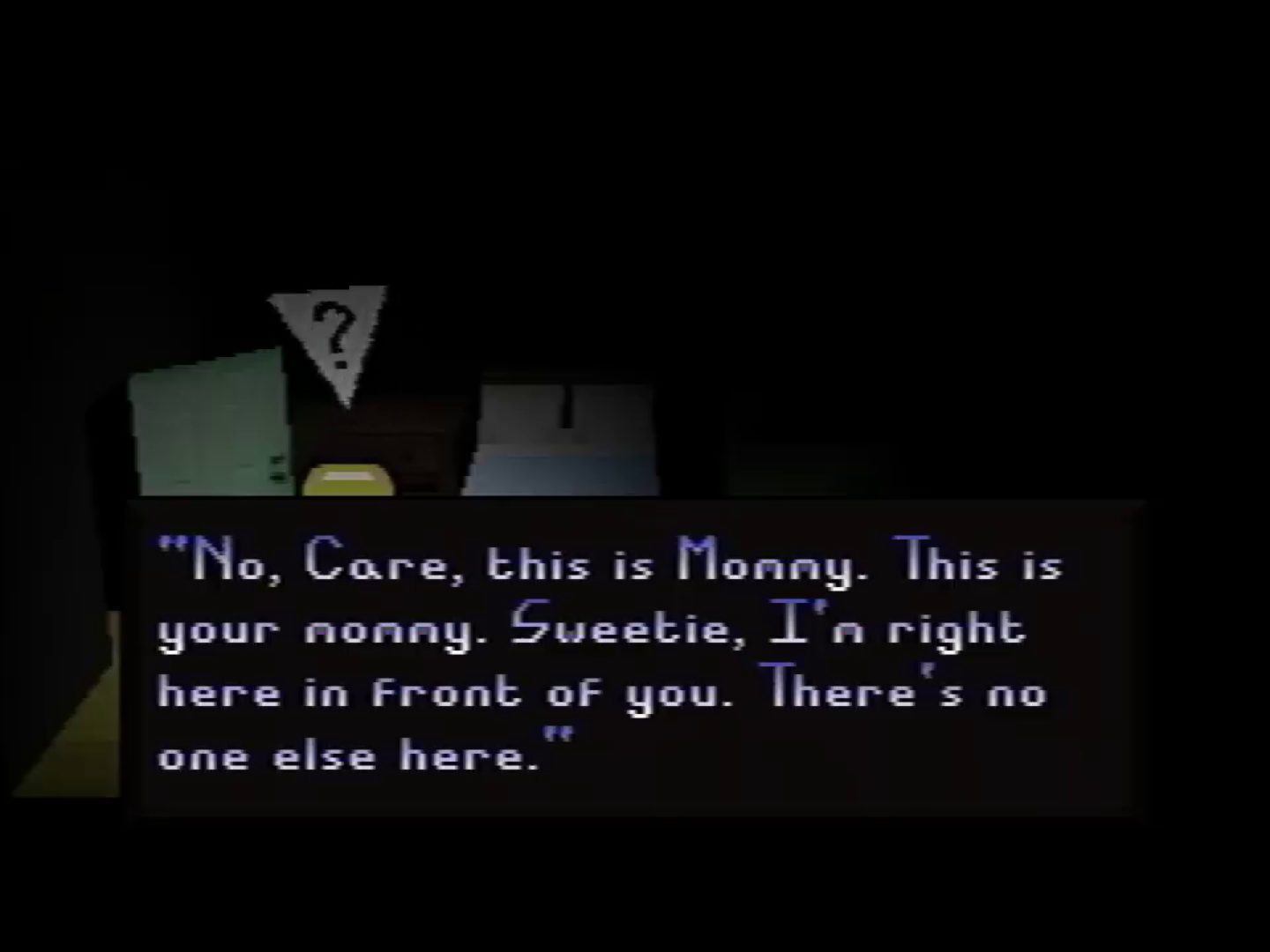

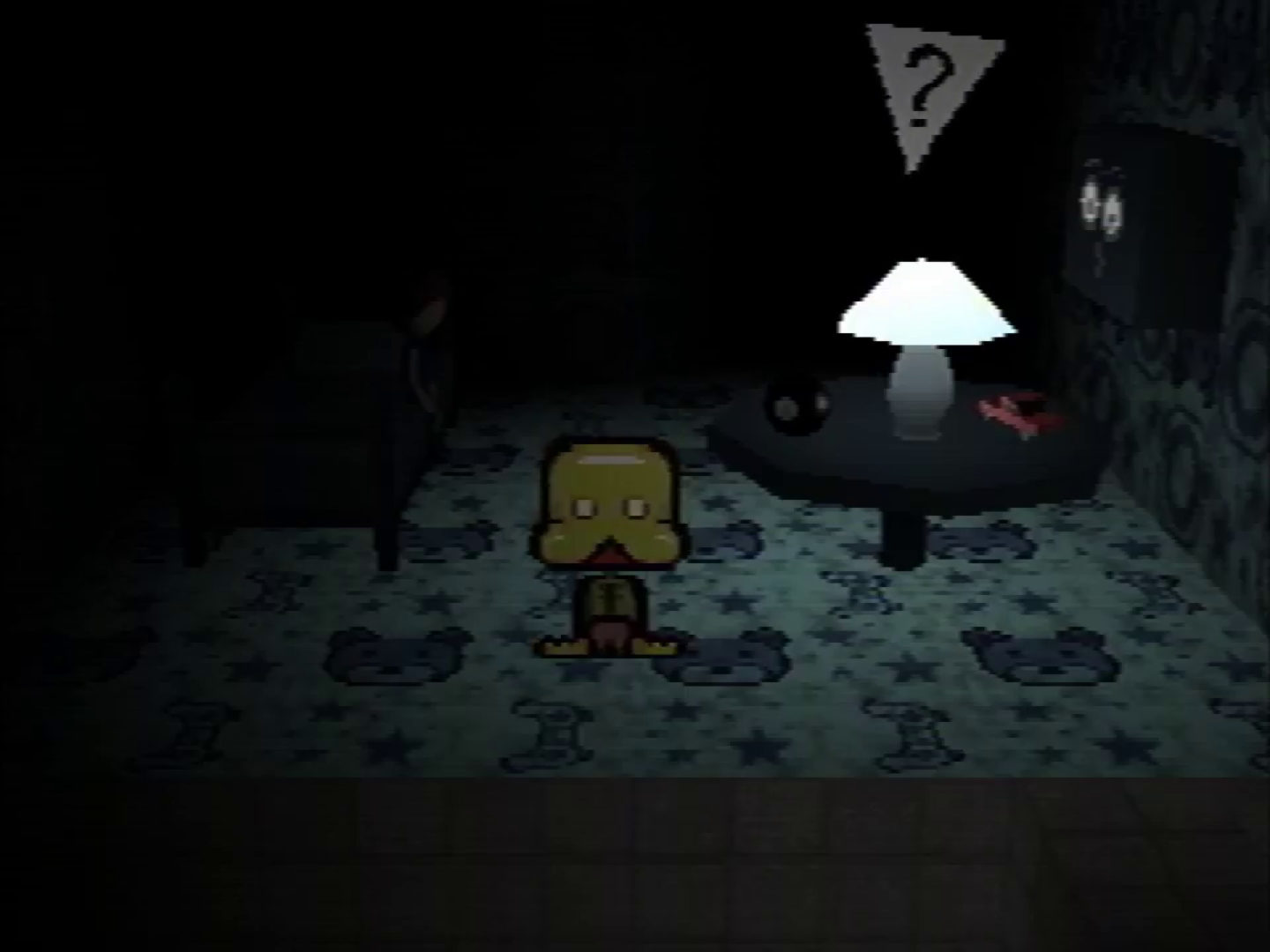

There’s a door that appears after a long period of searching a seemingly endless open field, which only opens after Paul lets the game run idle for a few minutes. A strange tune plays as the path forward is revealed. There’s a mirrored bedroom in which Paul acts as someone else’s reflection, which goes out of sync while the same music plays. “Quitter’s room” is written on the floor, and there’s a note on the wall that asks “Do you remember being born?”

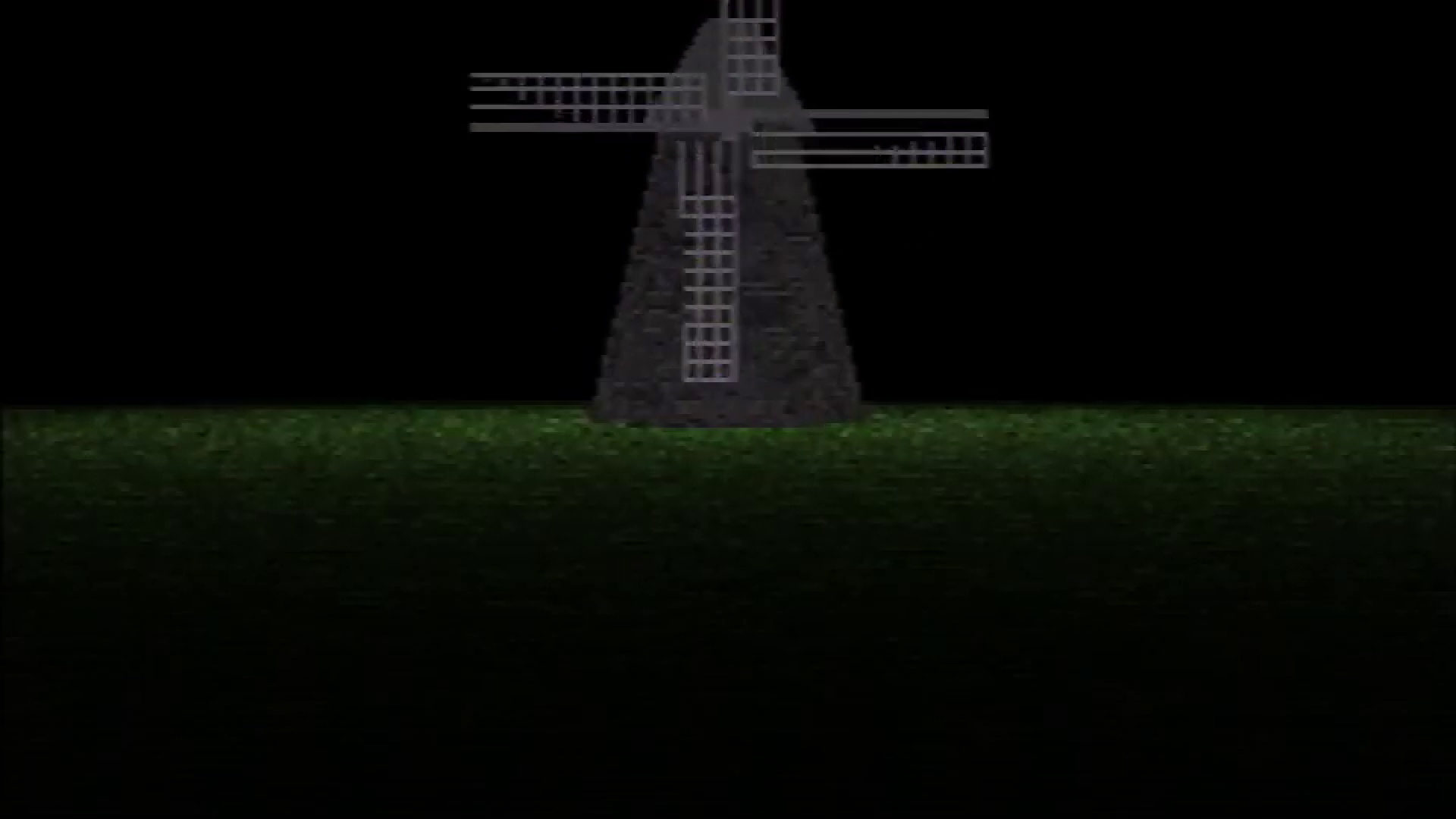

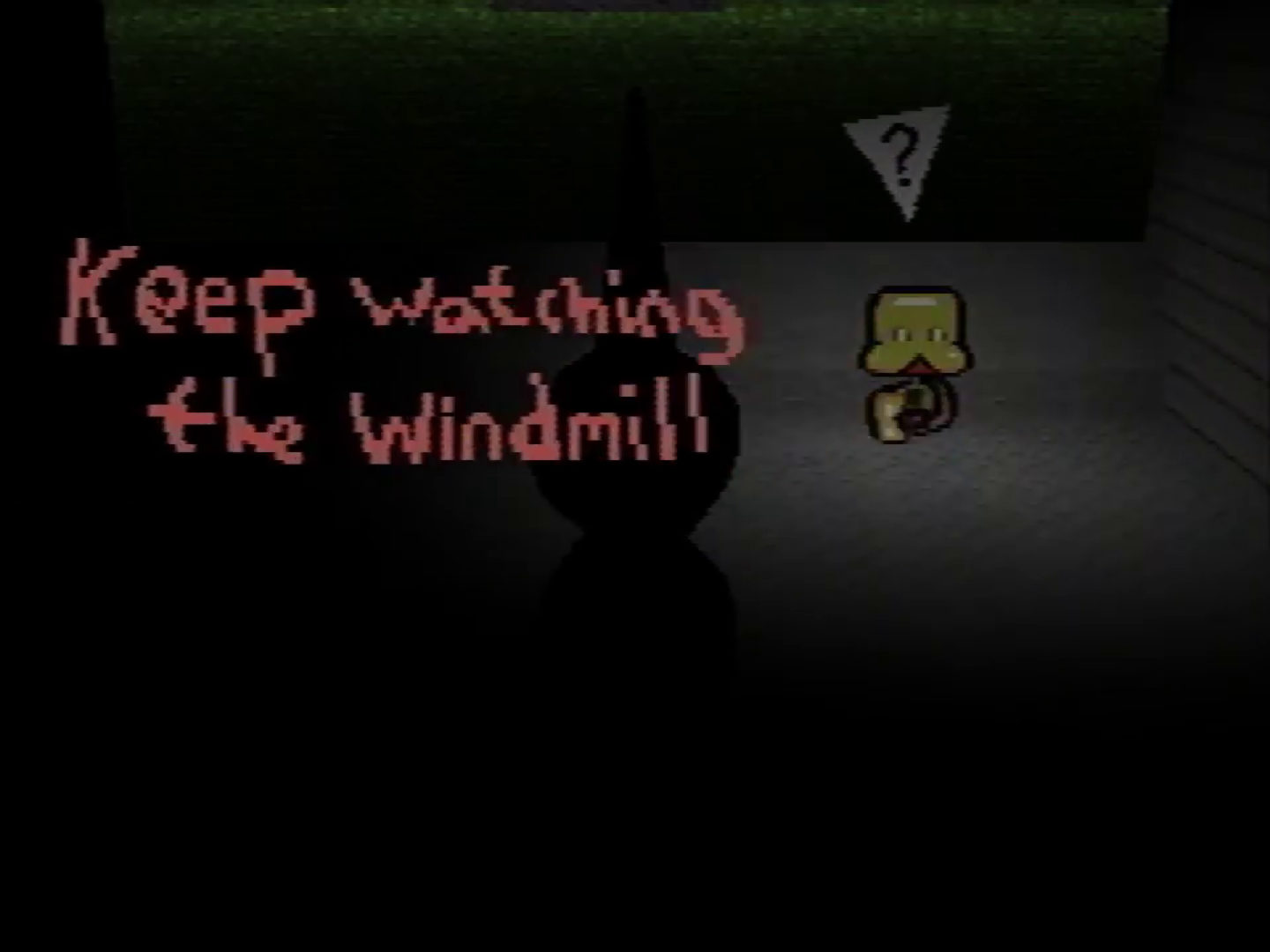

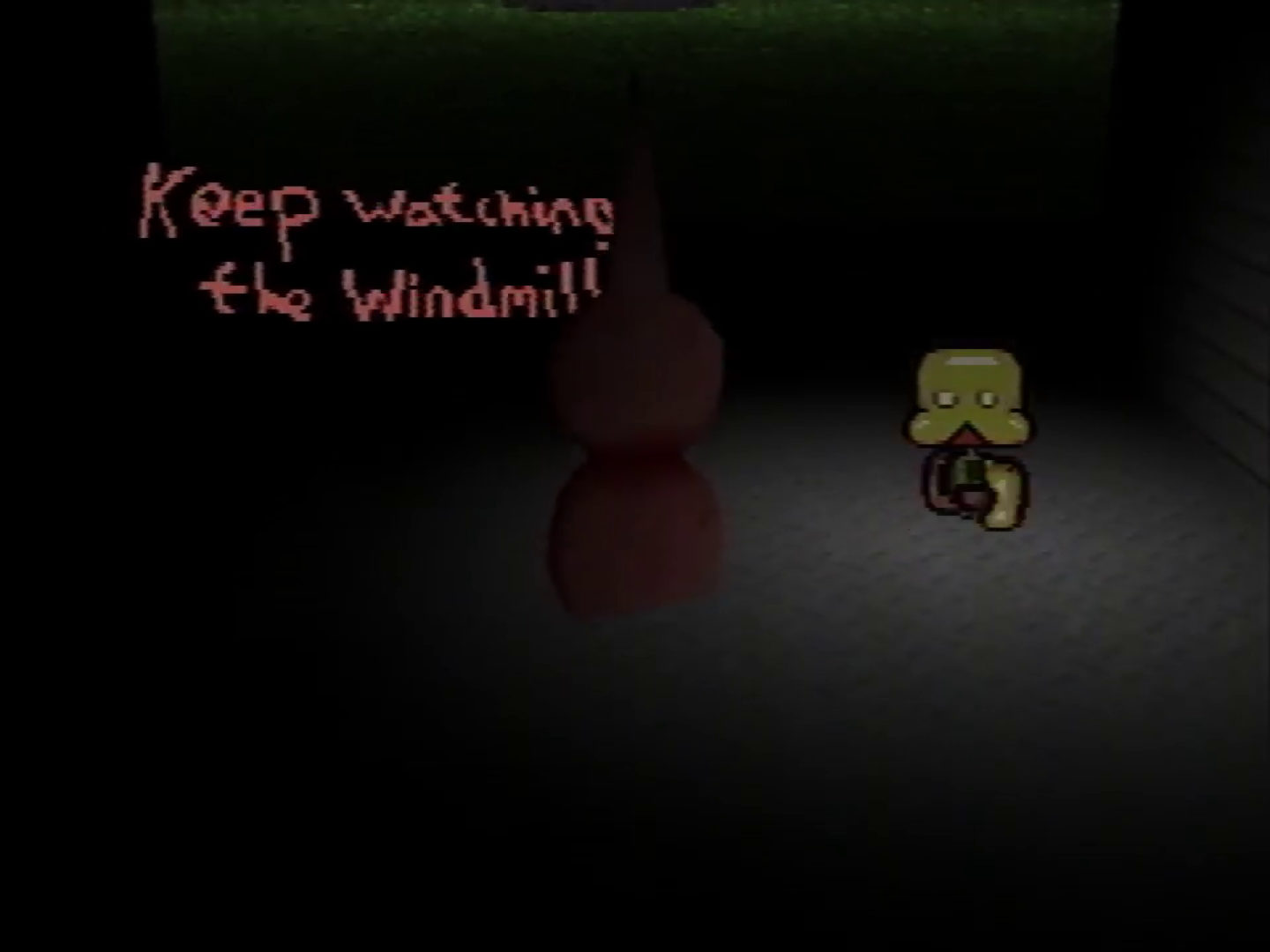

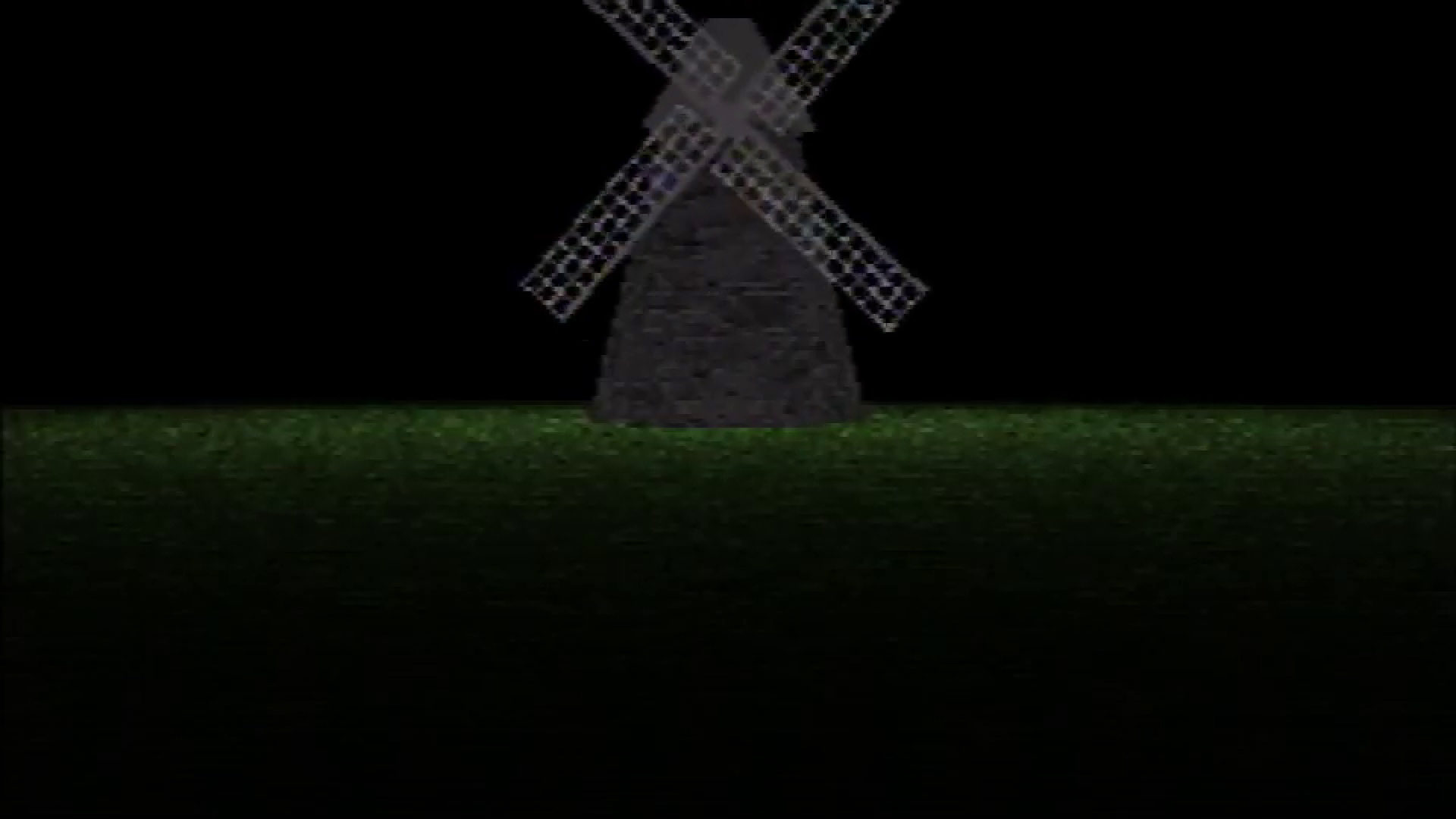

There’s a strange “tool” that looks like an awl, or a gourd, or a womb, which lets Paul ask it questions, but usually answers with “I don’t know.” This tool is seen drawn in crayon, over and over again, and hung on the walls of the passageway leading up to it. It tells Paul to “keep watching the windmill” that’s seen on a screen behind it—Paul later finds where the windmill should be, but sees nothing but its foundation, bare on the ground.

It’s a one of the series’ regular motifs: puzzles, challenges, and obscure hints that stretch the limits of what a player could be expected to solve or piece together. Each unusual moment adds a strange sense of apprehension that could really only work in the medium of fake Let’s Play videos.

“Each example has its own purpose, but in general, it felt important to me that I take advantage of the ‘fake game’ format,” Domenico said. “That meant doing things that I couldn’t reasonably do in a real game.”

It all creates a feeling of dread that’s hard to put a finger on. Domenico doesn’t think he’s the only person who wants that kind of experience in a horror work.

“I don’t even necessarily know what I want,” Domenico said. “But I always want something really strongly, and can’t find it. A lot of stuff on the internet these days is getting so, so close. People are actively looking for it now, whatever it is.”

Hello, folks. I guess this is for all of you, now

A day after the fourth video was published, it was shared to the public on a small subreddit called /r/creepygaming, by a user named “palescowitz.” (Domenico confirmed he was indeed the one behind the account.) The title of the post was fairly straightforward: “Videos of a mysterious unfinished PSX game from 1997, called ‘Petscop’. There’s something hiding in it.”

“I was expecting mixed reactions,” Domenico said. “I thought people might think it was stupid, and was bracing myself for that.”

That wasn’t quite what happened.

The replies were universally positive, and that initial Reddit post ended up being the only time Domenico ever needed to directly promote one of his videos. Viewers started latching on to all the connections and implications of everything and getting drawn into the uncanny atmosphere that left them ill at ease.

They noticed the hidden images in the loading screens and the things in the background that Paul didn’t seem to notice. It drew people into the narrative—and that was by design.

“There’s this thing, which Marble Hornets may have made popular, of involving people in your videos by hiding things in them. Giving off a feeling that there’s maybe more here that you aren’t seeing,” Domenico said. “That’s great, especially for the people who never find those hidden things. Just knowing there’s something that you aren’t seeing creates a great atmosphere for horror.”

It soon became clear to viewers that there were shapes, ideas, characters, and themes that were all repeated and tied together in ways that hinted at something going on that’s much larger than an unfinished game.

And so Petscop’s popularity began to grow. A community gathered around the videos: a subreddit, a wiki, a Discord server. Thousands, then tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands of people subscribed to the Petscop YouTube channel.

“After it started blowing up, I felt sick for a while, because I didn’t know what was going to happen. But after that wore off, it was just fun,” Domenico said. “It was such pure luck. It feels absurd sometimes.”

Part of the community became dedicated to finding connections and meanings. YouTube channels like Game Theory, Nightmare Masterclass, and Pyrocynical made their own analysis videos. In addition to the wiki, fans wrote a 129-page shared Google Doc documenting what they knew, all in the hopes of getting to the bottom of just what was happening.

Domenico tended not to look at those discussions. He found that reading the theories and discoveries was unsettling. “In general, it’s uncomfortable when people look at your work through a magnifying glass,” he said. “But also, people approach things in very, very different ways. I think that’s great, but I don’t need to see it all.”

He would, however, pop into the Discord and subreddit after he released a video. Viewers’ initial responses were something he found far more interesting than the in-depth speculation that followed.

“I liked reading immediate reactions, because those were more based on the feeling of the video,” Domenico said. “But those reactions were filtered through words, of course. It might have been nice to actually see more people watch the videos for the first time, as they were being released.”

You can’t go back in time

Domenico had been making games, music, and art for over a decade by the time he created Petscop. He’d never received anything close to this type of response to anything he’d made before.

Before Petscop, his game 8:Capsule, created for a 2010 contest in the TIGSource forums, was the project that had garnered the most attention. The rather abstract puzzle game requires players to figure out which objects to throw at which targets in order to progress to the next level.

It placed third in the contest and eventually faded into obscurity.

After Petscop ended, though, people started looking at Domenico’s old work again. The game that received the most attention, called Nifty, shares certain elements with his more-famous work. The two games are purportedly made by the same fictional company, and some of the same cryptic symbols are shared between them. Both have darker stories lurking beneath what, at first glance, appears to be an innocent, if quirky, game.

“I enjoyed that continuity. It felt like I’d been slowly developing this thing over time,” Domenico said. “There were a few people who played Nifty ‘back in the day,’ and I wanted to communicate that feeling to them as well.”

When Domenico started Nifty, he intended to create exactly the sort of simple, abstract puzzle game that it first appears to be on the surface. “That didn’t turn out to be very interesting,” he admitted.

To spice things up, he started making levels that caused things to go completely off-the-rails. The result was a game with outside-the-box puzzles that forced players to read the game’s config files, delete saves, and edit file contents.

“I was learning Game Maker, and I wanted to use all the features of Game Maker that I could for the puzzles,” Domenico explained.

It’s a growing organism

There’s also a very creepypasta-esque backstory hidden behind Nifty, involving hints at previous releases of the game that caused emotional attachment to its main character that eventually led to several cases of suicide.

It’s the kind of creepy story that appeals to Domenico—the kind where you feel a sense of dread not just for the characters on screen, but for yourself as well.

“It’s not that you’re scared of anything in particular. It’s like when you’re a kid, and you haven’t been in this universe long enough to have this really solidified feeling of what can and can’t happen in it,” Domenico said. “So it’s like, anything can happen. People could jump out of your TV, that kind of thing. I love trying to bring myself back to that. I think you can do it by messing with basic expectations, operating on a foreign set of rules, making it difficult to predict what’s going to happen.”

Domenico announced on Twitter that the game only has superficial similarities to Petscop, but now he admits that there’s more to it than that.

“I can’t deny that there’s a certain thematic continuity stretching across all that stuff. It’s more accurate to say that they aren’t canonically related.”

Despite being such an enigmatic piece of work with ties to his more popular creations, Domenico would rather people didn’t dig up his old stuff. “I’m not proud of that stuff, as it exists. I mean, that’s part of why I recycle ideas,” he said. “For the people who didn’t already know about my work, I’d rather Petscop bury those old things than draw attention to them. But of course, that’s not how it works.”

And yet, Domenico admits that when he finished Nifty, he couldn’t keep his mind off of what he had created. “Petscop evolved partly from Nifty,” he said. “I kept thinking about that game after I finished it. I developed a whole story around it, which I combined with other ideas I had, and it eventually became its own thing.”

You might be confused as to what happened

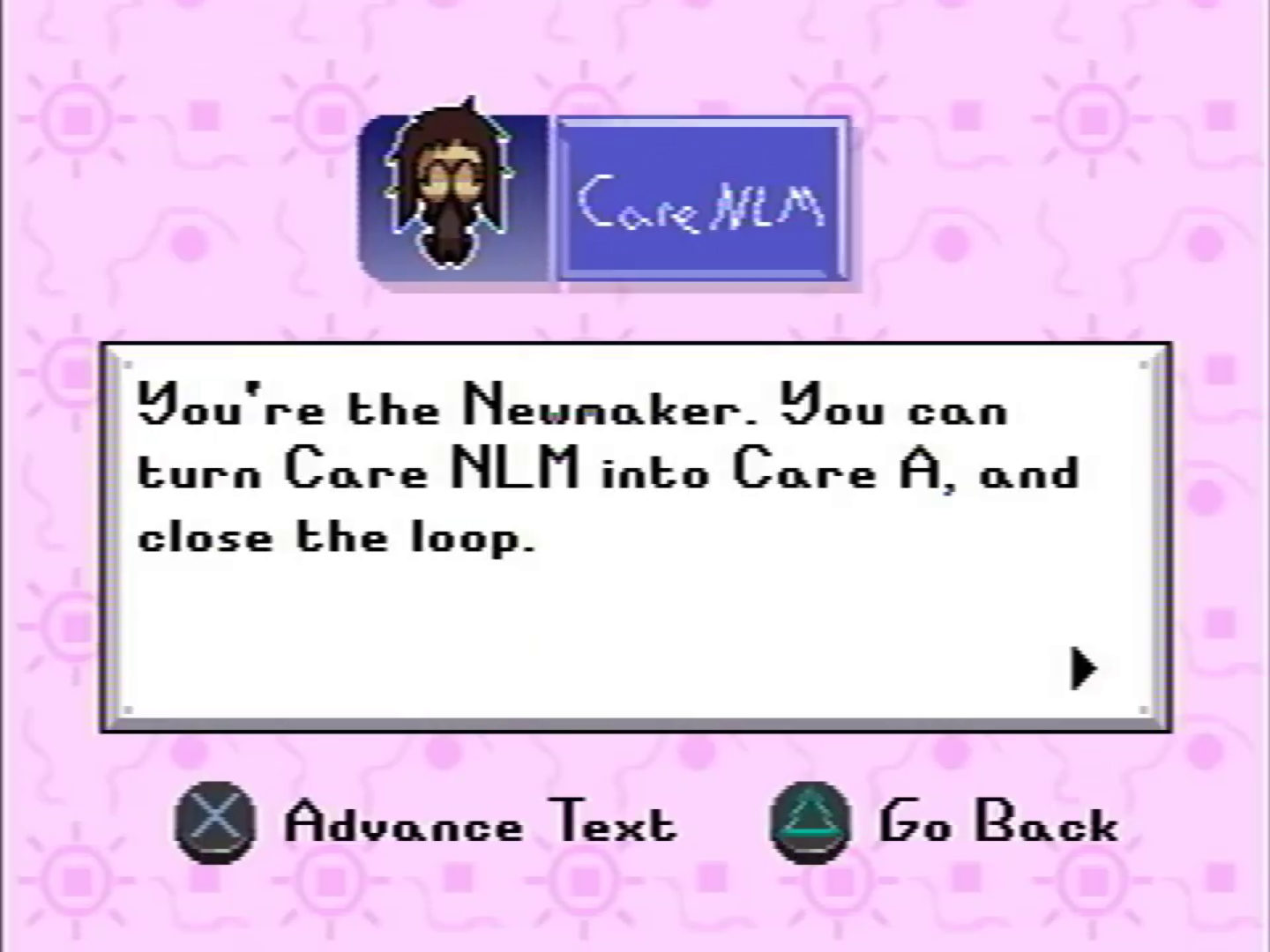

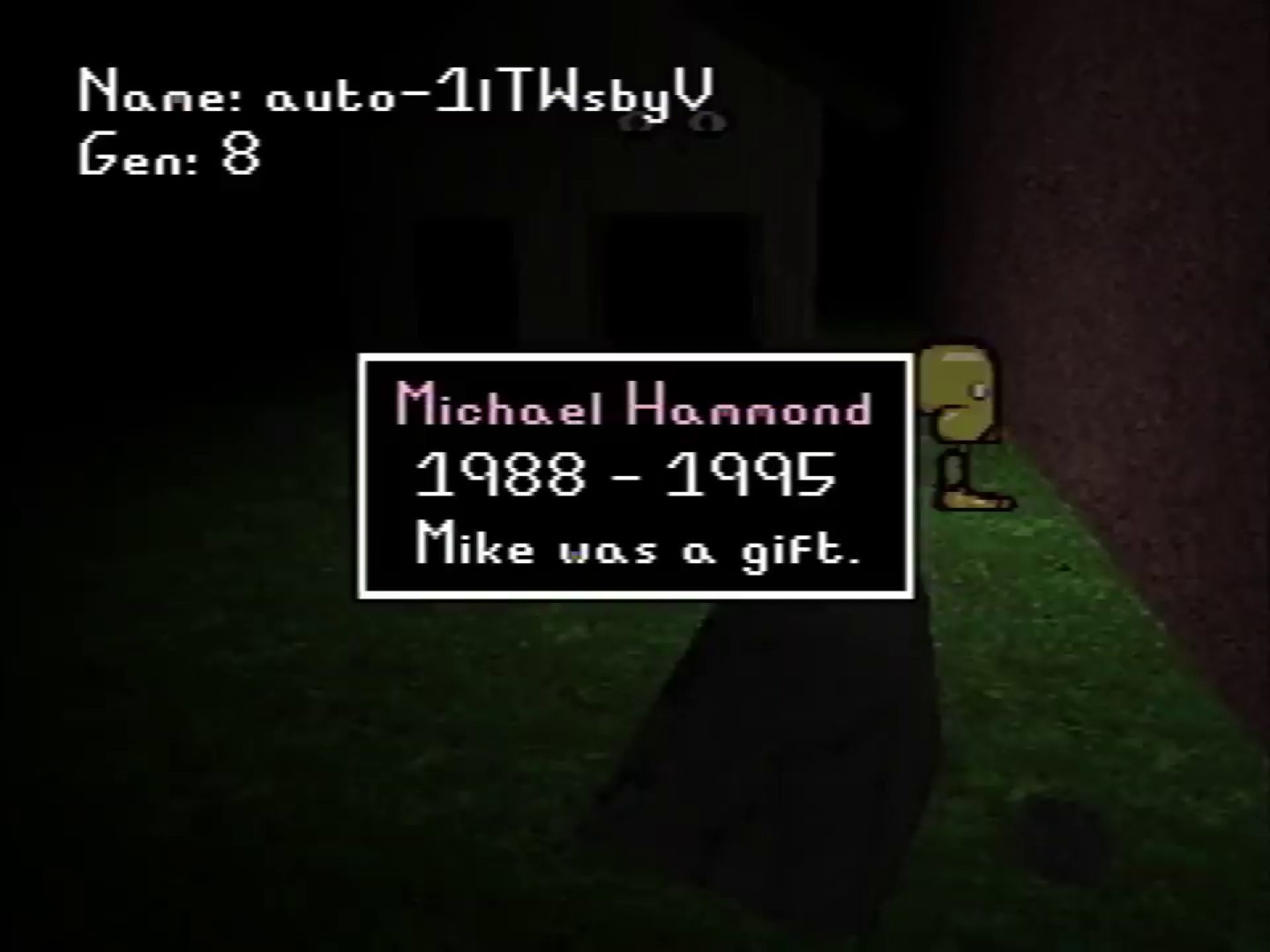

For anyone paying attention, the rough outline of Petscop’s narrative isn’t too difficult to hash out. It revolves around a man named Marvin, a tragedy that killed his childhood friend Lina, and an incident in which Marvin kidnaps his own daughter, whom he believes to be Lina reborn. There’s also a failed attempt to change a girl named Belle into someone named Tiara, a traffic accident, and a connection between Paul, the game, and his family.

But if that’s all there was to it, it wouldn’t have garnered such a dedicated fanbase that still wants to figure out its mysteries, and what different parts of the video imply about the story, the nature of the game, and what exactly it is that they’re watching.

What, for instance, does playing Stravinsky’s Septet have to do with rebirthing? What’s the purpose behind the two calendars from different years in the ghost room? What are we meant to learn from the video of dozens of pyramid-headed characters?

There is a story that ties it all together, Domenico said. He set forward with an idea of who the characters were, what their motivations were, and what the meaning behind the events was. Having that in place, he believes, means that viewers can intuitively sense that everything ties together.

He’s not going to tell us what he had in mind, though, and he allowed his gut feelings to influence what showed up in the videos.

“I chose what details I wanted to include, based on what felt good,” Domenico said. “Now that it’s over, that’s it. Saying more would be like extending the series.”

In fact, he intentionally left gaps in the story because he felt like adding too much detail would ruin the sense of ambiguity that he was aiming for. This led to him scrapping some work when he realized it set too many things in stone.

“Early on, I wrote a lot of stuff for a ‘Petscop Discovery Pages’ website that I was going to release with the first video, along with a developer journal. That material could have destroyed the series immediately,” Domenico said. “I used that website in a later video, too small to be readable, and that was the perfect amount of detail. You can just make out the pictures, and see how much text there is, and you’re informed of a page called ‘Your Child,’ and that’s all the information needed. I was so happy with that.”

He says his viewers seem to have understood most of the themes he was trying to get across. But if it was his goal to outright explain his intentions, he wouldn’t have made such a hard-to-penetrate series to begin with.

“There’s room for interpreting it in different ways, based on your own experiences and what you care about,” said Domenico. “I prefer not to explain it in words myself, because that would take away from personal interpretations, and because I think too much is lost in that translation into words.”

Everything you say will become the truth

Domenico has remained insistent that his viewers’ personal interpretations are more important than anything he had in his head when he made the videos. He’s too close to the work to accurately analyze it—anything he gets out of Petscop would be based on his thoughts while creating it, rather than the seeing what’s actually in the videos.

“After working on something for a long time, your perspective on it is really messed up,” Domenico said. “I say other people have a more valid perspective because, for better or worse, it’s more based on the work as it actually exists.”

Some of his fans have shown frustration at these statements, many of them having approached the series’ mysteries as something that they were meant to get to the bottom of through carefully inspecting all the details. That wasn’t Domenico’s intention.

“It’s not a puzzle to be solved, and there is nothing that I would call a ‘solution,’” he said. “I like ambiguity, not as a tease or a challenge, but as something that stands on its own.”

It’s not even that Domenico wants his fans to come up with their own stories about what happened—he just thinks that the sense of uncertainty and fear that comes with the series to be the main focus. “It’s not that I’m asking people to literally fill in all the blanks with their own answers, either. That’s fine, but if you do that, you’ve removed the ambiguity, and changed the atmosphere of the entire thing,” he said.

Even so, the hand of authorial intent is still visible in some elements of the series. Themes of childhood trauma and rebirth, for example, are impossible to miss.

“There’s this sort of abstract idea of being lost and corrupted in an irreparable way that just feels so deeply sad and scary. Lots of different ideas and images feed into this. Rebirth feeds into it easily,” Domenico said. “It doesn’t come from experience. I had a good childhood.”

Some things, you can’t rewrite

One thing that Petscop is not meant to be about, Domenico insists, is the death of Candace Newmaker. However, the series did make direct references to that tragedy.

Newmaker, originally born Candace Tiara Elmore, was a 10-year-old girl who died in April 2000 after her adoptive parents took her to an unlicensed therapist. The therapist wrapped her in a flannel sheet and covered her in pillows as part of a “rebirthing” ceremony. She suffocated inside.

In Petscop’s first 10 episodes, there are plenty of references to the tragedy. For instance, Paul’s player is referred to as “Newmaker,” the endless dark field is called the “Newmaker Plane,” and the label of “quitter’s room” appears to be a reference to how the therapist called Candace a “quitter” when she was unable to free herself from the wrappings.

These references took on a life of their own once they were discovered. Many people following the series fixated on them, with the belief spreading that Petscop was about Candace Newmaker.

This was not Domenico’s intent. After revealing himself as the creator of Petscop, Domenico tweeted out an admission that the references were intentional—and said that including them “was extremely stupid of me.” The tweet is still pinned to the top of his Twitter page.

The references, Domenico said, were only meant to tie into the themes of rebirth that are seen throughout the series. Looking back, he says he believes it wasn’t appropriate to reference a real-life tragedy in a work like Petscop.

“A decision like that, to reference a tragedy involving real people, should have a lot of weight to it. It should have been something I treated very carefully,” Domenico said. “I did not treat it carefully enough. But also, I feel that this series was just not the place for that kind of thing.”

When he came to this realization, he made a few changes to how the series would play out.

“The changes were subtle, because I was never gonna go much deeper with the references,” Domenico said. “Mainly, I avoided using the name Newmaker again. I didn’t want to emphasize it any more than I already had.”

We can play something else if you want

With Petscop now behind him, Domenico’s set his sights on another project—one that he says he’ll complete in its entirety before he starts revealing it to the public. One thing he will share is that it will apparently have some connection to the 1997 PC game Lego Island.

“I loved that game. It’s the silly and relaxed atmosphere, plus the mystery of it—I mean, at the time, I thought there were secrets, but actually I’d already seen everything,” Domenico said. “There’s not much to it. These days I also like it because it’s so rough and broken.”

Domenico said that there’ll still be an element of horror to the project, but that he plans to tell the story in a much more straightforward manner than Petscop. Other than that, he doesn’t have much that he wants to reveal yet.

“It’s still pretty early on,” Domenico said. “Though I have a lot planned, those plans usually change dramatically as a project goes on.”

He also sees this new endeavor as a welcome change of pace following a project that’s taken up the last few years of his life.

“I loved making Petscop, and I’m proud of it, and I’m happy that I get to move on to something else,” Domenico said.

Phillip Moyer is a Vegas-based journalist and lifetime game junkie. He grew up reading games magazines and chose his career path in hopes of one day writing for them. In addition to writing for EGM, he has been published in TheGamer and TouchArcade, and works at a local news station.