In April 2015, P.T. became the most high-profile casualty of digital distribution in recent memory. Released in August 2014 as a PlayStation 4 exclusive “playable teaser” for Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro’s Silent Hills, P.T. became a phenomenon in its own right. Critics showered the brief horror experience with accolades, and YouTubers churned out hundreds of reaction videos. Then, in the wake of a highly public falling out between Kojima and Konami, the publisher cancelled Silent Hills and eventually removed P.T. from the PlayStation Store. Players who didn’t already have a copy downloaded to their consoles lost access to the title forever.

For a game so popular to almost completely disappear in an era when preserving games should be easier than ever speaks to a larger issue: that publishers have almost sole discretion of what happens to their games. And P.T. isn’t the only victim of this phenomenon within the last few years. When Razer shut down the Ouya servers, it erased a small but significant chapter in Android gaming from existence.

But in both instances, dedicated preservationists have gone to extreme lengths to protect the software. PlayStation 4 owners have saved their copies of P.T. locally, and, as Nicole Carpenter recently reported for Vice, a grassroots movement searched for and downloaded every Ouya game possible. Even St.GIGA and Nintendo’s ill-fated, ahead-of-its time Satellaview, which used TV signals to broadcast downloadable games to Super Famicom Memory Pak owners back in the early ’90s has faithful dedicated to the cause of preserving its titles.

Noble as they are, amateur efforts to save games from extinction can only go so far. Limited by time and money, one person can only save so many games. Thankfully, as game publishing veers more in the direction of a digital model, even more formal efforts are on the rise and doing their best to legitimize video game preservation. But professional preservationists and historians are only just starting to catch up, while more games every day are in danger of fading away.

Video Game History Foundation founder and co-director Frank Cifaldi started as an amateur preservationist 20 years ago.

“I have been preserving video game history in one form or another myself since maybe 1999,” he told EGM. “It’s just always been my cause in life, and I’ve always done it as an individual while working various jobs, eventually in the video game industry itself. [Founding the Video Game History Foundation] was just a natural step to start the thing I thought should be in the world.”

After working as both a games journalist and a developer, Cifaldi decided in 2010 that he should start a nonprofit that furthered the preservation of games and game history. Five years later, Cifaldi quit his job to fully focus on incorporating a nonprofit, and formally launched the foundation in 2017. Lewin, who is also co-owner of the Seattle-based games retailer Pink Gorilla, reached out to Cifaldi after hearing about what he was trying to do.

Credit: Still taken from Video Game History Foundation video

“I feel like physical retail releases are pretty safe,” Lewin said. “There were a lot of people who were doing that already, but Frank was the first person I saw to be like, ‘No, we need to save the press releases to save the context around it. We need to know what people’s attitudes were around this, before and after the game’s launch and during development.’ That part has always been really interesting to me as a researcher. So that was like, good, someone gets that it’s more than just saving the games themselves.”

The VGHF takes a multipronged approach to preserving video game history. One of its biggest efforts is the reference collection, which is comprised of magazines, books, and other promotional and marketing materials from 1981 to 2000, the bulk of which comes directly from Cifaldi’s personal collection. Recently, Cifaldi and volunteers spent a month in Minneapolis combing through Game Informer’s archives and also received a hefty donation of Canard PC and PC Gamer issues from PR firm ICO Media. The endgame for all this is to establish a permanent library dedicated to archiving these print materials.

The foundation’s other major effort goes toward creating a massive online, searchable digital library that includes scans of game packaging, videos, marketing and PR items, and most importantly, playable binary code and internal development materials like source code.

It probably goes without saying that the latter materials are the hardest to get. Source code is among the most prized possessions of any game publisher. Letting other developers pick apart a game’s basic building blocks, especially if that game’s a hit, would be like a magician showing an audience of rivals how to perform her best tricks.

But for organizations like the VGHF, getting that source code isn’t about replicating a mega-hit title. It isn’t even about bragging rights (mostly). It’s about education and giving developers tools to not only make better games but to avoid mistakes that past developers have made.

“One of our goals is that video game source become educational tools instead of trade secrets,” Cifaldi said. “We believe that you’re not going to get better insight into how a game works and functions than you would actually being able to go inside the game and see how it works and functions and see, you know, cut content and documentation of how these tools work.”

Despite the foundation’s intentions, source code is near impossible to come by. When they do get access to it, it’s usually thanks to individual rights holders. Maybe the foundation’s best get so far was getting the source code to Disney’s Aladdin. Because it didn’t get the code from rights holders, Cifaldi said the foundation won’t publish the code. Instead, the VGHF did its own research and published its findings in an extensively detailed blog post.

The relatively recent launch of the Video Game History Foundation speaks to an emerging trend of collectors legitimizing their hobbies by incorporating. One of the most prominent examples of this phenomenon is the National Videogame Museum in Frisco, Texas.

John Hardie, Sean Kelly, and Joe Santulli started collecting video games in the early ’80s, and all three shared an interest in finding out more about the people who made the games they loved. Back then, the names of designers and developers were “closely guarded secrets,” according to Hardie, because publishers didn’t want competitors to poach their talent. During Atari’s Tramiel Technology era, Hardie occasionally cold-called the Atari division’s phone number and entered random extensions to speak to programmers and developers about their games and the people who made them.

It wasn’t until the early ’90s, however, that the three future founders of the museum would actually meet—at least through mailing lists and collector’s guides. In 1991, Santulli co-founded Digital Press, a collector’s guide and fanzine dedicated to documenting and archiving pricing and information about video games. A Nintendo obsessive, Santulli sought out experts in different manufacturers and publishers and enlisted Hardie to write about Atari and Kelly to write about Intellivision and Vectrex.

“We will put every ounce of information we knew into that guide,” Hardie said. “You could find out Easter eggs, and who wrote [the games], and maybe if it had a name change.”

“We were reading the chips and looking for messages and strings of text,” Kelly added. “There wasn’t an internet [back then]. Well, there was, but it was in its infancy. There really wasn’t a lot of information out there, so we were creating that information.” What made this process of tracking down information even more difficult was, even by 1991, a lot of the companies whose games and histories they were archiving were already gone.

Eventually, the trio met in person and participated in World of Atari in 1998, a resurrection of an old tradeshow event focused solely on Atari. It was a fun event, according to Hardie, but the group didn’t really connect with the plans the organizers had for the event.

“They were going to expand it and they had these big plans,” Hardie said. “It was going to be like a mini E3, and we didn’t really feel like that was the right direction. We felt that it should have been [about] collectors and more than Atari, so we split off and started our own show.”

That show, which would premiere in 1999, was the Classic Gaming Expo, and it would plant the seeds for what would eventually become the National Videogame Museum. Hosted occasionally in California but mostly in Las Vegas, the Expo was the first of its kind and ran until 2014. While the main focus was bringing industry figures like Activision co-founder and Pitfall designer David Crane, Apple’s Steve Wozniak, and Atari’s Nolan Bushnell to speak and allowing vendors to peddle their wares, another major draw for the show was a makeshift museum that Hardie, Kelly and Santulli built from their personal collections.

“The museum really took off,” Kelly said, “and every year, John, Joe and I were still doing the same thing we were doing before Classic Games Expo, which was gathering up stuff. ‘I got this, I found this.’ Every year, more stuff would show up at the museum, and the biggest question we got was, well, ‘Where can I see this outside of Las Vegas [at the Expo]?’”

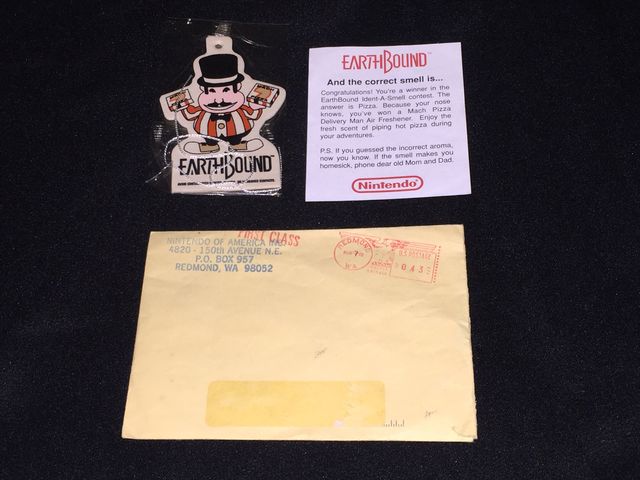

Credit: Still taken from National Videogame Museum promo video

In 2004, the three brought their museum to E3 for the first time, setting up an exhibit in Kentia Hall. Back then, Kentia Hall served as something like a respite from the madness and chaos of the main show floor—a place for “third parties and scrubs,” Hardie said with a chuckle. “We set up this crazy booth. We had a little arcade we had living rooms and it was just fantastic. The music was blasting people having a good time.”

At this year’s E3, the National Videogame Museum had a sizable exhibit in South Hall, right next to the Fortnite booth.

It took until 2009 for Hardie, Kelly, and Santulli to formally incorporate the museum as a nonprofit. Even at that point, they still didn’t have a home base. They were still traveling with their exhibit, shipping their collections out to Las Vegas where they’d pick everything up and drive it around the West in a truck, doing around five shows a year over the course of a few weeks, all while still holding down day jobs.

Then, in February 2012, the museum founders brought their exhibit to the D.I.C.E. Summit, where they met Gearbox president Randy Pitchford, who suggested that they visit Frisco, which at the time was starting to become a professional hub for the industry. The idea was to meet with city officials to see if Frisco would be a good fit as the museum’s permanent home.

“Randy sometimes gets a bad rap, but he’s the most generous guy I know,” Hardie said. “He flew us down, he put us up. He used to run Gearbox Community Days where they would do auctions, and that money was always earmarked for us as a charity—because we were a nonprofit—to help us grow and continue.”

After their initial pitch meeting with the city, Kelly continued to fly down from Chicago for “like a hundred meetings.” The city liked the idea of having a permanent video game museum and invested $1.3 million in a space for the trio within the Frisco Discovery Center, which was also home to the city’s Sci-Tech Center, a black box theater, and an art gallery.

After over a decade of not making any money from the Classic Gaming Expo (or, if they did, investing it into more arcade machines for the exhibit), the National Videogame Museum finally had somewhere to settle down.

In the run-up to the opening, all three founders were flying back and forth every two or three weeks to build the museum themselves, even going so far as to set up all 11,000 feet of CAT5 cable running through the exhibits. Even now, Hardie is the only one of the trio who now lives in Frisco, having retired from his job at Verizon to focus on the museum full time. Kelly and Santulli still live in Chicago and New Jersey, respectively, where they run video game stores in addition to their work on the museum.

Opening its doors to the public in 2014, the National Videogame Museum houses 10,000 square feet of exhibition space, with an additional 1,500 to 2,000 square feet of storage. On top of that, the museum owners have seven more storage units located off-site that are “bursting at the seams,” Kelly said. Even this doesn’t match the original vision of the museum, which required 50,000 square feet for 56 exhibits. Currently, the museum has 20 exhibits, but there are eventual plans for expansion.

The most grandiose plan for the museum—one cut from the initial design—is a 10,000 square foot research library where pretty much every game in the collection would be available to play on every system, alongside press kits and other printed materials for those games. On top of all that, the library would have “little Makerspace-ish type rooms” where, for example, developers could back up the data on old cartridges onto EPROM burners for their own personal use—or to donate to the museum, if they want.

The National Videogame Museum is a testament to video games as cultural and historical artifacts, which legitimizes the industry as a whole, and that’s in part because it isn’t just three guys putting some stuff behind glass cases.

“We have curators that are experienced in the museum,” Hardie said. “We do run a lean [operation], but that was one of the areas that had to be, you know, professionals come in.”

An example of this, Hardie said, is how paperwork and press materials are preserved. “Everything gets put in a bag with acid-free backing,” he explained. “We have microchamber paper that prevents the yellowing and PVC-free bags, and everything is catalogued in our system.”

It’s this kind of professionalism that legitimizes video game preservation as a historical necessity. No one knows that better than Dr. Jon-Paul Dyson, the vice president of exhibits and director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games at the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York. The museum has the world’s largest collection of play—toys, dolls, video games, and more—at half a million artifacts in its collection, with 60,000 of those coming from its electronic games collection. A portion of the gaming artifacts are on display in both permanent and temporary exhibits that contextualize the games within history and give attendees a chance to play for themselves. The Strong’s particular interest in video games is in the transformative effect that playing and learning have on each other, and how older methods of play compare to video games.

“There’s a conversation going on between these older play forms and games,” Dyson said. “The same play mechanic may be expressed very differently in different games. For instance, shooter games—what’s the relationship between playing cops and robbers in your backyard and playing Fortnite on your screen? There’s parallel play going on there—continuity but also change. They’re both shooter games to some extent, but they’re expressed differently. So our interest [in video games] grew out of this deeper look at play.”

Dyson has been at the Strong for over two decades. While studying for his Ph.D in American history with a concentration in 19th century cultural history, he received a call from the Strong asking if he was interested in a job. Dyson was able to combine his interest in video games—he got his start with the text-based mainframe games and of the ’70s—with his formal training as a historian to apply the same methodology that scholars use to investigate other fields of study.

Because video game preservation is such a young field, and because most of the scholars and professionals working in this field are gamers themselves, there is a personal and emotional motivation to making sure that the history of games is recorded, more so than in other historical fields. For Dyson, it’s important that the personal motivations for recording video game history don’t compromise the objective, professional approaches to conservation.

“We treat conservation in ways that are unique to, say, an arcade game,” Dyson said, “but in many ways the principles are the same that a museum would apply to whatever method of conservation you’re using.”

Dyson gave an example of how they would restore an arcade machine while also making sure that its original condition could be reinstated. “We might use a glue that, in the future, someone could go back and undo that. Or we might take the panel off and replace the panel but keep the original panel so that you could go back and restore it to its original condition. I think there’s both an emotional drive to our interest in the subject, but in the same token, that needs to yoke to professional, objective approaches.”

This is where Dyson sees the interchange between amateur collectors and professional preservationists and scholars being hugely important. As he pointed out, “Oftentimes in any cultural medium… like art, for instance, a new style comes along, it’s going to be private collectors who see that it’s important, then institutions tend to follow. It’s the same thing with video games.”

What collectors and amateur preservationists perhaps lack in training, reach, and long-term stability, they gain in the kind of flexibility that larger institutions don’t have. In that sense, there’s an equitable, almost yin and yang relationship between the two different groups.

“Each has a different role to play,” Dyson said. As an analogy, he compared them to different kinds of boats: “One is like the smaller destroyer or [patrol torpedo] boat zipping around, that’s the individual [collector], while the institution, like a museum, is more like a battleship or an aircraft carrier. It can’t turn around as quickly, but there are other things that it does well.”

How people experience video game history is another important question when it comes to preservation. When it comes to literary history, there’s only one real way to experience a book. The same can be said about film, though you could say that reading a film’s script is just as important as watching it on screen (not to mention the difference between watching on a theater screen and a laptop screen).

Video games are even more complex. Not only are they an audio-visual medium, but the most important aspects of understanding and experiencing games derive from player interaction.

Both the National Videogame Museum and the Strong National Museum of Play have dedicated spaces where attendees can get hands-on experience with certain games. The NVM has an entire area at the end of its tour where attendees can experience a faithful recreation of an ’80s arcade, complete with dozens of cabinets. The Strong has dedicated stations where attendees can play games as well, with a focus on giving participants a novel way of experiencing those games. This is especially true in one of the museum’s most popular exhibits: a giant Super Mario Bros. controller that multiple people can play at once.

“If we just had a normal version of Super Mario Bros., people wouldn’t play it,” Dyson said. “Well, they might play it, but [the giant controller] is a unique experience. One of the most interesting things that happens around these moments is the intergenerational conversation that’s happening. A lot of parents coming in, this is the game they cut their teeth on as kids, and it’s probably one of the few games where they can beat their kids, and you see this conversation going on where they’re teaching their kids how to jump or what they need to do in the game. And so it’s a great chance for dialogue, and that’s something we’re interested in, people thinking critically about these things.”

Unfortunately, it’s just not possible—at least at the moment—for either museum to make every game ever made available to play and experience. If video games are something to be studied, even the most niche, retro titles should be available, if not to play, than at least to view. In 2011, the Strong received a six-figure grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which it used in part to fund the International Center for the History of Electronic Games’ Video Game Play Capture Project, which Dyson estimated recorded 4,000 games from before 2005 on their original systems. It’s impressive, but smaller, independent outfits have been doing a similar thing for much longer and in much greater numbers.

That’s where World of Longplays is the destroyer to these museums’ battleships. Boasting over 800,000 subscribers on its YouTube channel, World of Longplays posts a new longplay video every 12 hours, seven days a week, adding up to a whopping 730 uploads each year, and that doesn’t even include the “quicklook” videos that function as not-so-longplays for smaller titles.

World of Longplays comes from a tradition of gamers documenting in great detail how games play from beginning to end. The term “longplay” has been around since the ’80s, when German magazine 64’er first used it to describe written walkthroughs. In the early 2000s, Reinhard “Monty Mole” Klinksiek adopted the term to describe full-length video playthroughs of Commodore 64 games.

In 2005, Mikael “Hipoonios” Persson started RecordedAmigaGames, a now-defunct website similar to Monty Mole’s that focused on Amiga games. Gerhard “ScHlAuChi” Weihrauch, one of World of Longplays’ main admins, grew up playing Amiga and started uploading his own videos to RecordedAmigaGames. Eventually, the site grew in popularity among Amiga fans and, as more members joined, interest in uploading longplays moved beyond a single gaming platform. Eventually, in 2008, World of Longplays was born.

Weihrauch estimated that, as of June 2019, there are over 10,000 games represented on World of Longplays’ YouTube channel, which has been active since June 2006. Over the last 13 years, these videos have been viewed over 800 million times. The group currently has videos scheduled all the way to early November, with new videos being uploaded every day.

Many people volunteer to upload videos, but there’s a small core group that keeps everything organized. Along with Weihrauch, admins Mad-Matt, NPI, and Reinc help organize the site and upload videos to Archive.org, which itself has almost 30,000 video game-related videos, including reviews and more. Weihrauch also works with kireev20000 and Frederikct112 to upload the videos to YouTube, while admin Connor maintains the FTP and Asnivor helps with the website tech. Finally, there are several noted longtime longplayers: Spazbo4, RickyC, Tsunao, JagOfTroy, Ravenlord, Ironclaw, Geekmeister, Eino, Genbu, xRavenXP, Mariofan88, mihaibest, Lemmy556, georgc3, and JohnX895. It’s a massive effort undertaken by only a handful of people, and the only funding comes from ads on the videos—this in spite of the fact that videos are often demonetized due to copyright claims. Weihrauch estimated that he currently has over 6,000 content ID match emails in his inbox.

World of Longplays didn’t necessarily start as an effort to preserve games, at least not for Weihrauch. As a game designer and developer, Weihrauch found that capturing gameplay was a convenient way to communicate design decisions to coworkers. Similarly to how the Video Game History Foundation views source code, Weihrauch viewed longplays as educational tools for developers, especially for games that weren’t readily available, as well as a way to give fans of older games a chance to experience them again. But as the group continued to put together more longplays, the idea of hosting a video museum on YouTube in order to preserve the experience of lost or rare games began to make sense.

“I’m coming from the game design side and I saw, especially in the digital age, lots of games disappear forever,” he said. “There’s no physical releases anymore for some games. So that’s how I saw, yeah, we have to document them correctly.”

Early on, there weren’t many rules for how longplayers recorded the games. Since it was mostly for fun, participants could just record gameplay and submit them to the site. Over time, however, and especially as preservation became more of a focus for the group, it became more important to formalize how these games were recorded. Longplayers recording open-world games have to at least finish the main quest and all the story-based sidequests. For simpler, more linear games, 100 percent completion is encouraged, but for more narrative-based titles like those from developer Quantic Dreams that have multiple different story choices and outcomes, longplayers only need to complete one playthrough.

A key aspect to World of Longplays’ guidelines is recording games in the best possible video quality, and the best way to do that is to use emulators—not just because of the quality you can get from emulated games, but also because they basically make recording longplays possible without the videos being way longer than they need to be. While not every console has been emulated yet—at least not to World of Longplays’ standards—certain multisystem emulators like TASVideos’ Bizhawk presents nearly perfect recreations of the original systems that make recording longplays possible in the first place. These emulator makers “are the real heroes,” Weihrauch said. World of Longplays even has a Patreon that it uses to fund one of the Bizhawk devs to support more systems.

Emulators are especially handy when it comes to recording longplays because of tool-assisted emulation. Generally used for tool-assisted speedruns and superplays, this kind of emulation combines the use of save states with recorded button inputs per frame to present a “recording” of gameplay that cuts out all the stuff that might cause playthroughs to be longer than necessary—deaths, for example. YouTuber Bismuth smartly compares the process to how a player piano reads and performs music. (It’s also exactly how older games like Super Mario Bros. and the original Doom used to run “demos” on their startup screens.) The use of tool-assistance means that, especially for more difficult titles, the time a longplayer spends recording gameplay is usually significantly longer than the end product you can watch on YouTube. Weihrauch, for example, played DonPachi for the Sega Saturn and spent 8 hours recording what ended up being a two-and-a-half-hour video.

Even after all that effort, YouTube’s aggressive demonetization policy and automatic copyright strikes present a challenge to World of Longplays.

“Our museum-like approach is not something YT likes,” Weihrauch told me over Skype chat. “There is probably 30 percent of our videos claimed by random [claims]. When [our network Screenwave Media] asked [YouTube] to treat us more fair, they basically said, ‘All you do is play the games and upload the videos without much effort involved—so that doesn’t get any protection.’”

Weihrauch sees “broken” copyright laws as a larger hindrance to game preservation, not just when it comes to funding World of Longplays’ videos.

This is especially true for publishers like Strictly Limited Games and Unseen 64 who want to re-release old and possibly forgotten games to bring them to a new audience. Weihrauch witnessed this firsthand when he took part in Project Hardcore—a restoration of DICE’s previously unreleased 1994 Mega Drive and Amiga game.

“Who owns [Hardcore]?” Weihrauch asked hypothetically. Originally, the game was signed by developer and publisher Psygnosis, who was mostly known as an Amiga developer before moving its publishing efforts to include Mega Drive and other consoles. Sony acquired the development arm of Psygnosis and turned it into Sony Studio Liverpool, while Psygnosis’ publishing arm remained independent. However, in 2000, Sony also acquired Psygnosis’ publishing rights, too.

This is where it got really hinky. “Psygnosis had contracts in paper format with DICE, which was a four-man team at the time,” Weihrauch explained. “Who has contracts in paper that are 25 years old? Which company has that? Sony said, ‘Yeah, we probably have the rights since we bought Psygnosis, but we don’t have any paper contracts anymore, so how would we know if we actually have the rights?’ And that’s a problem with a lot of these old games.”

Another example of older games falling victim to the mess that are copyright laws and publishing rights is Turrican. That game “was originally published by THQ. THQ went bankrupt, and no one knew who had the rights. [German development studio] Factor 5 tried to get back the rights, but THQ was bankrupt and no one knew who had the rights. So trying to get back the rights so they could make a new Turrican game took them almost 10 years.”

These kind of Kafkaesque scenarios for developers who just want to bring their old games to a newer audience might seem frustrating, but they’re endemic to the video game industry, and they make preservation efforts that much more difficult.

The most common obstacles to preservation efforts, according to those I talked to for this story, are the publishers themselves—though not without good reason.

Of the VGHF’s efforts to acquire more source code, Cifaldi said that “the main concern is basically that people will acquire trade secrets, like the secret sauce of a game, and then reproduce it. The other main concern being a little scarier, which is we don’t own the entirety of this source, so we can’t donate it,” which speaks to the jumbled mess that is video game intellectual property rights.

For Dyson at the Strong, most of the museum’s archival materials have come from creators like Will Wright, Broderbund Software’s Doug Carlston, and the folks at Toys for Bob who created the Skylanders series. When it comes to working with bigger publishers, however, it’s all about finding a win-win approach to gaining materials.

“The focus of most people who are in the industry right now is their current project,” Dyson said, “and I totally get that from a business point of view. They have payroll, they have to meet certain targets… so history is less of a concern for most people.” In that case, the Strong tries to find ways to work with publishers that will benefit both them and the museum, such as celebrating the anniversary of a major title that’s getting rereleased.

The National Videogame Museum founders have come to the same conclusions. “The real difficulty is that we have to show how preserving their history can positively affect their bottom line,” Kelly said. “Unfortunately, that’s what most [executives] are concerned with, is that ‘we need to make some money to survive.’ You know, we understand that, but it’s difficult to show definitively how preserving the history of your company and what you guys have done affects your bottom line.”

Sometimes, however, preservationists and historians can do just that. Kelly recalled when Activision was releasing a collection of its Atari 2600 games for the original PlayStation, but the company didn’t even have the data for those games: “I had to actually read the Activision cartridges and supply them with ROM images for their own Atari 2600 games. Nobody in the company knew how to get the data off of the cartridges, so they were reaching out to hobbyists, and I had to illegally read their cartridge and provide them with the ROM images.”

We’ve moved beyond the time of the Atari 2600, when publishers simply saw their games as disposable, and bigger companies are getting somewhat better at archiving and maintaining their own histories, but with live service becoming the business model for the biggest publishers, games can change drastically over the course of their life spans. As Eric Kaltman wrote in his 2016 essay “Current Game Preservation is Not Enough” for Stanford’s How They Got Game program, “The incredible production rates of current games, and the inability to currently preserve them all will lead to a situation where predominantly single player, non-networked games are overrepresented (or in many cases the only representatives) in the playable record.”

This commentary seems even more prescient in 2019. The gigantic Fortnite booth that towered over the National Videogame Museum’s exhibit at E3 represents a game that changes dramatically every few weeks. What happened to Fortnite’s original map? Does Epic have it safely stored away somewhere?

It’s a struggle even to just get press materials from publishers—something that would take no time for a PR person to send to the museum, Hardie said.

“Twenty years from now, John and I will be really old men and we probably won’t care very much anymore,” Kelly said, laughing, “but who’s the next generation of museum curators? Where are they going to find that stuff? So that’s part of what we do. We store as much stuff as we can, but some stuff, there’s no files we can download. All you do is go online and view crap.”

Even though video game preservation is still in its infancy, it’s already come a long way. The Computerspielemuseum in Berlin has over 300 exhibits in its permanent collection, and the Game Preservation Society has been collecting and restoring games from before the 2000s for at least eight years now. All of these ventures are born out of passion for games and the industry—an emotional, personal connection leads preservationists to preserve, at least for now.

“When interest in video game preservation and history first started, it was mostly passionate individuals who were motivated by their own personal love of the media,” Dyson said. “What you’re going to find as the field develops is that more and more people are coming in and doing this work because they recognize it’s important, not just because they have a personal stake in it.”

Header image courtesy of the Strong National Museum of Play

Michael Goroff has written and edited for EGM since 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @gogogoroff.