In 2006, Bloomberg published a deep dive into the then three-year-old Second Life called “My Virtual Life.” Written as though a traveller had just stumbled into a bizarre foreign city, the article describes the “seriously weird” Second Life as the “unholy offspring” of The Matrix, MySpace, and eBay. It also compares Second Life to World of Warcraft, otherwise apparently known as the business world’s “new golf.” In the most dated prediction, we’re told that virtual worlds like Second Life could become “far more intuitive portals into the vast resources of the entire Internet than today’s World Wide Web” and could even challenge Windows as a framework for presenting software to users. It also highlights the money being made by users and the corporations rushing to invest. It’s a perfect summation of the hype that was impossible for Second Life to live up to and that “My Virtual Life” was far from alone in creating.

To put that hype in context, Second Life’s 2003 launch preceded World of Warcraft’s by 17 months and came when only 54.7 percent of American homes had an internet connection. The idea of socialising in an expansive digital world, and using built-in scripting languages and modeling tools to fill that world with your own content, was still new to many people. Today, the average child learns about these concepts (and their limitations) through games like Minecraft or Roblox, but SL looked like a mature, broad, and high profile step-up from EverQuest, which targeted hardcore gamers, and the cartoonish simplicity of Habbo Hotel, which was aimed at teens. There was confusion and uncertainty over what SL could and should be used for, so an assumption grew that it could do anything.

But by 2007, as Second Life was appearing in CSI and The Office, Wired was turning bearish on a service they had previously proselytized. In 2009, Forbes declared that the Second Life hype had “fizzled.” And by 2011, Slate and TechRadar were running “Hey, whatever happened to Second Life?” retrospectives as though it was a relic of antiquity. Reports of Second Life’s death were as exaggerated as claims that it would revolutionize technology, as it continues to chug along today for the benefit of a hardcore fanbase. But between 2006 and 2009, as the Second Life hype was building the steam it would need to dramatically barrel over a cliff, five guides to Second Life were published by Wiley with the official cooperation of SL developer Linden Lab.

The books are time capsules of the hopes of dozens of SL users and Linden staff interviewed for them, and looking back on them today reveals a medley of the mundane, overoptimistic, and insane. There are predictions of long term government and media presence mixed with basic etiquette tips mixed with a look at Second Life’s sex work community. Of the four “organizations who earn substantial amounts of money blogging about Second Life,” one URL now sells steroids, one is now home to an IT company, and one stopped publishing in 2013 (but briefly resurfaced in 2016 to write a bizarre interview with the obnoxious neo-Nazi troll weev).

A general purpose book called Second Life: The Official Guide came first, in 2006. It received a second edition in 2008, the year that also saw the release of The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Second Life: Making Money in the Metaverse, Creating Your World: The Official Guide to Advanced Content Creation for Second Life, and Scripting Your World: The Official Guide to Second Life Scripting. The series closed with 2009’s The Second Life Grid: The Official Guide to Communication, Collaboration, and Community Engagement. Glossy textbooks of 300 to 400 pages each, together they can take a reader from learning the basic concepts of a digital world to programming their own tip jars for the Second Life business they might decide to open. Some of their predictions for the future of Second Life are reasonable, and some make “My Virtual Life” look restrained. So what did these books get right, and what did they get horrendously wrong?

While some of the users and locations they mention are still active, they’re mostly a collection of dead and dormant links that serve as a testament to the same raw speed of the internet that the books warn you about trying to keep up with. The web presences of Amethyst Rosencrans and Nyteshade Vesperia, quoted for their expertise in running Second Life sex businesses, have both petered out, although not before Vesperia was able to debut 2015’s X5 Cock with “incredibly realistic mesh design” and “unparalleled BDSM owner control.” Genvieve Hutchence, who in The Entrepreneur’s Guide gives advice on Second Life escort work, has only a Facebook page with nothing but four 2008 photos from SL to her digital name today. Professor Sadovnycha, owner of the BDSM education Princess Reform School is also MIA, as are Second Life fashion blogger Celebrity Trollop, owner of “one of the virtual world’s oldest and most popular clubs” Jenna Fairplay, Second Life real estate moguls The Otherland Group, “founder and CEO of … one of the largest content creation companies in SL” Aimee Weber, and many, many more.

There are scattered exceptions to the exodus, like Nexeus Fatale. Introduced in The Entrepreneur’s Guide as “one of the leading DJs in Second Life,” Nexeus worked the SL launch parties for Popular Science and The L Word, among other high profile gigs. In the book, he lauds the ease of interacting with his audience and the variety of music that residents appreciate, while advising aspiring DJs on how to avoid scams and copyright pitfalls. While his DJing days ended in 2012 he’s still an SL regular, telling me, “What keeps me active is that I get to explore. I try new things out, I do absolutely no-work-what-so-ever. But I appreciate it more because I’m a part of a bunch of communities. And that’s what I think Second Life has really begun to turn into, kind of a virtual Reddit.”

So while it’s easy to flip through these books and conclude that the world has long since moved on, but Second Life didn’t die so much as it quietly powered through the insane expectations that were created for it. In 2019 the Second Life community forums saw a spirited discussion on “Tipping Guidelines for Gentlemen Clubs” (in another throwback, one employee of a Second Life club comments, “Most of the women I work with, myself included are professional phone sex operators”). In the game’s subreddit just shy of 6,000 users share screenshots, discuss their favorite in-world creations, offer shopping deals with slick videos, and troubleshoot technical problems. Complaints that Second Life is dead and requests for tips on getting into SL can be found on the same page.

As of 2017 there were a reported 600,000 active accounts, with contemporary concurrent users hovering around a maximum of 45,000. Even accounting for some bot activity, that’s better than a legacy MMO of comparable age like EverQuest. No SL user will again grace the front page of Business Week because of all the money they’ve been making, but no one is predicting an imminent plug-pulling either.

The Official Guide’s 11 credited authors include Wagner James Au, who was Linden’s “embedded journalist” for Second Life’s first three years and who still covers SL and other virtual worlds on his blog. He compared the “hype phase” of ’06 to ’08 to the “recent euphoria over Bitcoin and social media and Fortnite, all mashed together into a single package—because Second Life had all those aspects.”

So when you see that all the heralded government, corporate, and media clients left Second Life almost as soon as they entered it, it’s hard not to view their retreat as a sign of failure. Vestiges may remain, but the NBA no longer monitors its “basketball fan’s paradise” where fans can view “real-time 3-D diagrams of games as they’re played,” Coke isn’t still slinging merchandise, and the SL Reuters bureau is long dead. But, as The Second Life Grid writer Kimberly Rufer-Bach explains, the reality was more complicated.

“When the first real-world organizations came into SL, they were mostly educational institutions quietly doing small research projects. But then came the marketing projects, which generated and lived on hype. It was not realistic to figure a copy of a real-world store was going to make big bucks selling virtual shoes or shirts. There weren’t yet enough avatars in SL to make enough money. Plus, they were competing against established brands in shops run by SL [Residents].

“Similarly, I don’t think anyone figured that the SL userbase would visit a company’s virtual shop and then run out to buy real-world items. Leveraging the hype was all about getting press for your organization by being one of the first to enter into this cutting-edge virtual world. For a while it was a sure thing; hire some SL developer to establish your organization’s presence, and you would reap lots of profitable press coverage. Because of this, SL unfortunately experienced a flood of carpetbaggers promising clients unrealistic things that couldn’t really be done with the platform, while underpaying Resident content creators, sometimes disappearing without paying at all.”

That’s not to say that Second Life was a hapless victim of corporate bullies. The Official Guide encourages you to “Go on a scavenger hunt on Microsoft’s island, take a Sentra or a customized Solstice for a spin around a race track, go surfing on the Weather Channel’s beach, hang out with fans of Showtime’s The L Word in a re-creation of the show’s locations, then play around in IBM’s codestation developer sandbox. … These companies and their experiences be joined [sic] by countless others, providing residents with a chance (if they’re interested) to merge real-world consumerism with their second lives.”

In an interview for The Entrepreneur’s Guide, Linden Lab CTO Cory Ondrejka went further in painting a picture of Second Life as a corporate utopia. “Even with video conferencing, you can’t really get up, move around, pace. … And Second Life helps with [that]. You have place, embodiment, and a method for having real-world style conversations a la a cocktail party (i.e., multiple, parallel conversations). I think the first new opportunity is going to be helping companies that have dispersed work forces save money on recruiting, on-boarding, training, and collaboration. This is a lot like what IBM has said they are working on. But they are just scratching the surface.”

Ondrejka went on to speculate on international business relations, saying, “In the real world, if you want to do a business meeting, you’d hire a simultaneous translator. In Second Life, you could have a HUD attachment that allows you to request translation between language A and language B which hits a web service, pages available translators, and tells you their rates per minute. They log in, stand with you, and now you conduct the meeting just like you would in the real world. But that would just be the start. … Think about using Second Life to set up a direct connection to tailors in Asia. You build the outfit you want in Second Life, they pull it from the client, combine it with your real-world dimensions, and FedEx you bespoke clothing. It could be cheap for you in terms of custom clothing—say US$100 an outfit—and still be very profitable for them.”

Ondrejka left Linden in 2007, before The Entrepreneur’s Guide was even published, and in 2010 Linden killed Second Life Enterprise, which offered secure, troll-resistant environments to companies like IBM that had, by that point, largely vanished from SL. One corporate client dubbed its use of the platform a “costly mistake.” Slack, a vastly simpler workplace collaboration tool, has over 10 million active users today.

It turned out that business in Second Life worked when it involved Second Life, when you were selling cool clothes, running a fun social hangout, or offering more erotic animations. But no one really wanted an elaborate digital façade for their non-SL business dealings. In a section called “Helping Outside Customers Understand What Second Life Is About” that now looks prescient, a user recounts a story where “an outside female client came into Second Life and happened upon a Gorean slave girl. ‘It was not pretty,’ Foolish said of the client’s reaction to seeing a female avatar in a slave-like situation. ‘But the fact is, if she was warned and educated about the fact that nobody in Second Life can really be forced to do anything, the situation might have been avoided.” That may have been true, but why talk your clients into conducting business in an environment that also caters to Gorean slave girls in the first place? SL doesn’t host business meetings anymore, but people are still “Looking to get into GOR” today.

The Entrepreneur’s Guide was written by tech journalist Daniel Terdiman, who was one of the most prolific writers on Second Life at the time. Reflecting on his book, he told me, “SL was one of the most-exciting topics in technology. Every big name you can think of was opening up in SL, and while there were obviously major problems (usability being the most threatening), it looked like it could grow to be a major platform with millions of users, tons of brands, and a flourishing economy. That notoriety was why I was able to get a book contract very quickly. Of course, with every hype cycle comes a crash, and in SL’s case the crash came so quickly that by the time the book came out we were already well past hype and into the skepticism cycle. Brands were pulling out, and we had trouble selling the book.”

The unsustainable hype was produced in part by the fact that, to outsiders, it was never entirely clear what you were supposed to do in Second Life. Articles like “My Virtual Life” continually lumped SL in with MMOs like World of Warcraft even though WoW’s “endless medieval-style quest for virtual gold and power” had little to do with SL’s social and business aspects. Even the terminology was confusing. Do you play SL? Use it? The press tended to say “gamers” or “users” even as Linden pushed “Residents.”

But confusion for some meant a blank slate for others. Dr. Karen Zita Haigh, who co-wrote Scripting Your World, had “literally never heard of the thing” before a colleague asked her to collaborate on the book. Haigh, a software engineer whose extensive resume includes work for NASA and DARPA, was intrigued by a virtual world that revolved around construction instead of weaponry. “It seemed like a really cool environment. I liked the idea that people could build their own things. My sister-in-law, she lived in the States, but her mom lived in Poland. They got on Second Life together to go shopping. Women playing computer games was not statistically common. I take a look at the abstract, and I thought they needed someone with a little bit of a different perspective than nerdy guys.”

Scripting Your World is the most technical of the books, walking readers through programming basics using examples like a bee that searches out flowers in your virtual yard. The need for the book seemed clear: “From a documentation perspective, [Second Life] was crowdsourced, so the documentation wasn’t reliable as you wanted it to be. That’s why you needed a textbook.”

Haigh highlighted two key aspects that made scripting in Second Life accessible to the masses: It was relatively easy to jump in and start learning, and it let users produce fun outcomes. “They did event based programming really well. That’s one of the things that’s really tough for new programmers to understand, this idea that you’re not in control, something else is. I had never run into an event-based programming language that was well-documented, they sort of assume everyone is going to understand it. I certainly had never been taught it, I picked it up as I went along.”

And picking it up was exactly what the book let otherwise novice programmers do. “We got comments from reviewers saying ‘I never did any programming before in my life, but I was able to do it.’ It was typically something simple, but they could do it. The nice thing about Second Life as a teaching construct is that you got immediate feedback on how well your system was working. And it was tangible, it was interesting. The whole way they handled particle effects was really cool. You as an end user could control very ephemeral things. That [had previously been] really tough to give a user access to.”

But Haigh soon lost interest in Second Life once she had solved the technical puzzles it offered. “I really enjoyed seeing how far I could push the rules. [For example], how small can you make things and still make them useful? Once I had exhausted all the possibilities I logged on a few times, I set up a little shop. But my interest was the scripting, the programming, the making it do cool things. But it was sort of like ‘Now what?’ I didn’t have a new challenge I could tackle.”

Answering the question of “Now what?” is where Rufer-Bach’s book, and the book James Au worked on, came in. To the extremely online, a book that has to introduce the concept of furries and cyberpunks feels like a tutorial for your baffled grandparents. Sentences like “Clad in fashions of a bygone time, usually in black or other dark colors, and perhaps accessorized by large jewels, vampires tend to live in richly appointed, atmospheric regions where it’s always night,” read like comical anachronisms.

But the books had to normalize a culture that was building for years before it hit the mainstream. Rufer-Bach, who was an active content creator in Second Life, explained, “My book was intended to answer the questions that I was asked all the time by my clients. I would get questions like, ‘What’s a Furry, and is a Neko a Furry or something else, and can my avatar somehow shake hands to greet the Neko that is coming to the meeting, or do we bow or something instead?’ [My clients] were very aware that there are cultural differences in etiquette in real places, and probably in virtual ones, too. No one wants to accidentally have bad manners.”

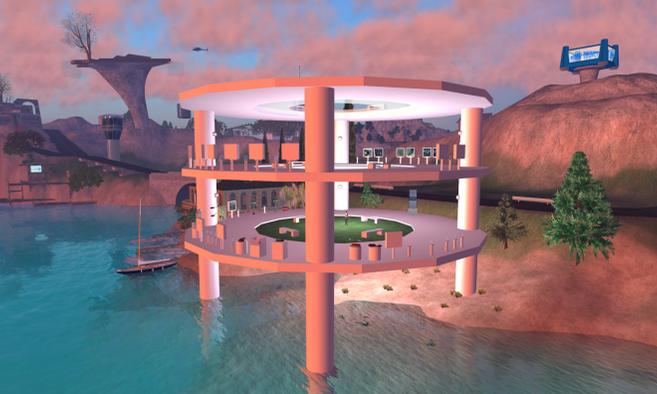

Credit: Liden Lab / Virtual Worlds for Adults

Rufer-Bach stressed that her clients had productive fun playing around in Second Life. Not coincidentally, the kind of clients that she mentioned, such as “immersive language-learning projects, particularly the British Council,” were making inherent use of the medium instead of just being there for the sake of it, and were therefore not the kind getting a lot of media attention. Again, The Official Guide is proud to highlight celebrity appearances by Bruce Willis, Arianna Huffington, Duran Duran, Oasis, Frank Miller, Cory Doctorow, William Gibson, Kurt Vonnegut, and a host of politicians, leading to a beautifully ridiculous photo captioned “Judge Richard Posner and a Furry fan.” But it’s unlikely that Kurt Vonnegut was sticking around after his interview to buy virtual Reeboks.

Credit: Linden Lab

It was instead people like Nexeus who stayed and embodied SL’s core userbase. Describing himself as someone who wanted to be a DJ from the time he was a kid making mixtapes with an FM radio and a cassette recorder, Nexeus DJed in Anarchy Online before taking the skills he’d learned to SL, which offered him an infrastructure and tools that he otherwise never would have had access to. “Virtual worlds fascinated me because of their ability to be living, breathing storybooks. These worlds often didn’t have a voice and style similar to mine, [so] I felt that not only could I provide something unique to help enrich the storytelling (in the case of Anarchy Online) or to enhance an experience (in the case of Second Life) but I could also try something ground-breaking.”

The appeal for Nexeus was that the game’s social spaces were defined by the users, not built into a game with its own rules and lore. “I would be hired for a fashion show, where there’s planning [of a model’s pacing and clothes], and a reaction based on how that was all presented. There were also events where people performed as cover bands of popular artists, but had a DJ [for] the pre- and post-show. Then there were club parties and special events hosted in themed locations. Unlike a game environment, I would never know what the crowd would look like or how they would react. If I were performing an event that was underwater, and playing a song that was slow and dark, I could tell the audience to change into something that glowed. H&R Block had me do a few events… there wasn’t anything really normal, everything was unusual because at the time everything that was being done was new.”

Credit: Nexeus Fatale via Facebook

That Nexeus found himself doing shows for both SL regulars and a tax preparation company highlights the push and pull SL experienced between the hype and the needs of its dedicated base. “The hype was exhilarating. WoW made virtual worlds, as a concept, easy to grasp. It allowed for Second Life, a world where you can build and be anything you want to be, just that much more enticing. It really felt that we were all the pioneers of something that had arrived. The media hype felt justified. The problem was while they would cover some of the amazing things within Second Life, they would also find the clickbait that revolved around sex and sexuality. It was a double-edged sword. Second Life allowed people to express themselves creatively, professionally, but also sexually. That last bit was often [the focus]. I personally felt [that was misguided]. Some of us were very annoyed that, while all of these brands were entering the space and we were doing amazing creative things, the hype would hover around THAT.”

There was certainly no shortage of sex gossip, with one 2007 column declaring “Whatever brings you to SL, you’ll soon find that sex is everywhere” and a 2008 piece gawking at a marriage that was supposedly ruined after the husband “romped with two virtual floozies” standing out as lurid examples. But the final two chapters of The Official Guide, “A Cultural Timeline” and “The Future and Impact of Second Life,” further highlight Linden’s own divided focus between SL’s core users and its media darling status. The timeline is introduced with overwrought claims like “‘I’m not building a game,’ Philip Linden once said, ‘I’m building a new country.’ And in many ways, the history of Second Life thus far resembles the first centuries of America itself.” But when Linden is able to get out of its own way, there’s also legitimately compelling information, like SL becoming a surreal battleground between supporters and detractors of the Iraq War, how SL came at the right place at the right time to attract a furry community, and how the co-owners of an adult animation and toy store became a real life couple.

The speculation on Second Life’s future opens with an acknowledgment of the residents that power it, saying, “As long as the residents themselves are creative and inventive, then there will be new things to see, new places to go, and new concepts to explore.” Then it’s implied that SL’s growth “could well be world-changing” and speculated that “It’s quite likely that 3D spaces will become an integral part of the online experience in the very near future, for a very large number of people.” The example use case is “being able to click through a [news] story and get launched into a 3D re-creation of the location where the story took place, where you could walk around and discuss the events with other readers who happened to be there at the same time.” Today the idea of a walking comments section with real-time access to voice output sounds horrifying.

Linden’s own hype reaches its loftiest with comments like “Imagine being able to access from SL from literally anywhere [with wearable computing], holding conversations across worlds, or overlaying your friend’s SL avatar on them when you see them in your first life,” and “What excites me the most about the future of Second Life is its potential to fundamentally improve the human condition.” Second Life may not have improved the human condition, but it certainly highlighted certain aspects of it. Terdiman referenced an infamous 2006 interview that was invaded by a horde of trolls wielding flying penises. In 2016 Justin and Griffin McElroy’s YouTube series Monster Factory dickishly (but hilariously) crashed a serious philosophical discussion group with their demand for dogs to be given the vote. Early attempts at high-minded self-governance also ended in failure and the installment of regulations by Linden, like a libertarian city-state suddenly realising that it needed tax revenue to function.

But that emphasis on the users who will be doing the work remains, even if the heroism of that work was wildly overstated. According to Rufer-Bach, “The hype washed over and through the virtual world, but the sorts of projects that preceded the hype had strong roots and didn’t all wash away, and some are still flourishing. Residents are still doing what Residents have always done in Second Life.”

Just what are Residents still doing? James Au provided some highlights. “The majority treat Second Life like a kind of Sims-type dollhouse for their avatar, tricking it out with the latest user-made fashion/skins/accessories/housewares. Second Life users who create and sell content make as much money from Second Life as [Linden] does. Probably the second biggest niche are roleplay communities, who’ve created roleplay regions inspired by Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Fallout, etc. Then third is likely a sub-niche of extreme adult roleplay, some of which has led to a huge lawsuit. There’s also a small but very active community which reflects Second Life’s glory years, when it was embraced as a platform for creating art and imparting 3D-based education, and for using it as a tool for real life therapy. For instance, there’s a community for using SL to address Parkinson symptoms.”

Nexeus, who for a time transferred his skills to real-life New York City bars, stepped back from nine years of online DJing when the money dried up, and when it just stopped being fun. “[When] the big real world companies I was working with [left] I had to go back to DJing community events [all the time]. Which was fine for a while, but the value that people had for DJs decreased. Maybe this is egotistical of me, but I think I set the bar for a lot of DJs in Second Life. I wrote a few articles that were widely read, I mentored many DJs. When I head to events now, I hear [DJs] using the exact same formula I would years ago, and I don’t think I helped people realize that DJing, like all things, evolves. I also lost sight of the prize. I got involved in many things that drew my focus from what I was enjoying in Second Life. I think if I stuck to being the community guy who provided entertainment I would be happier about my experience in the platform.”

Still, Nexeus seems content with where the aging platform is at. “In many ways it feels like it kept the original goal of the platform. It still has a vibrant community, which I find surprising and interesting. There’s a lot to improve, but I don’t think there’s the pressure it had to do it now or else. Things can be thought through, communities can be developed and people [can] make the decisions about what they want to see and enjoy and have. Its technology still has the same limitations, [it’s] still a resource hog. It still relies on downloading a program to run it. I couldn’t give someone a link to hop on and join my events. But I think part of its legacy will be when you see truly immersive experiences that aren’t gimmicks, that provide value for users and marketing for companies.”

Ironically, accessibility is perhaps now Second Life’s biggest problem. There’s 16 years worth of history, geography, and terminology intimidated newcomers need to absorb, and code can spaghetti into a nightmare. Au explained that “Many of the content creators, being novices, don’t always optimize their mesh models; consequently, Second Life is extremely difficult to use as a social experience, because the frame rate has been utterly borked by high poly mesh content.” Second Life essentially still exists to cater to long-time Second Life fans.

These books were all massive projects for their writers. Rufer-Bach described a year-long writing process that involved pulling completed chapters out of the hands of her copyeditor so she could revise based on sudden changes in SL. Terdiman worked for six months on top of his day job, an “extremely challenging” process that at points was “significantly behind schedule.” And Haigh worked “every weekend full time for eight months. The really frustrating thing was that after all of that work, the book comes out, it’s gorgeous, all of us are super thrilled with how it looks, great reviews were coming out, people seemed to love it. And a month later it got [pirated]. It popped up everywhere, and it [killed sales].”

But in reflecting on the legacy of both their own work and Second Life, they saw far more positives than negatives. Rufer-Bach, who saw The Second Life Grid be adapted as a university textbook, said, “From that community have come friendships, marriages, and children. A friend of mine redecorated her virtual house over and over, then homes of friends, then other avatars’ homes. Eventually, we didn’t see her inworld so much, because she learned so much that she closed her virtual interior decorating business and started a real-world interior decorating business! I watched friends without previous experience learning to make avatar dresses or write code in SL, until they learned so much they ended up with new real-world careers as artists or programmers.”

Haigh, whose book was also used in schools to teach introductory programming, saw Second Life as laying the groundwork for games like Minecraft and Roblox that rely on user-created content. “I think it impacted the gaming industry, broadly. I don’t know if Minecraft would exist without having Second Life come before it. There’s a lot of things that they broke ground on. And by making it essentially crowdsourced, people who wanted a capability would build it. People, as a society, tend to be far more creative than the engineers you hire for a company.”

Credit: Linden Lab

Terdiman also highlighted the platform’s open-ended nature. “I think SL will always be remembered for being extremely innovative when it came to allowing users to create and do whatever they wanted. If you had the technical chops to achieve something in SL, the platform more or less allowed you to do that. That no-rules approach made it seem exciting and unusual. In the end, that same approach probably got it in trouble. But there hasn’t been another virtual world that has given users the creative freedom SL did, and I’m not sure there will be any time soon. Platform developers are scared of the consequences of unfettered creative freedom, and I can understand that. It’s just a shame we haven’t seen more of it.”

The Final Chapter of The Official Guide closes with the bombastic: “People will use this interface to help manage and publish their lives, explore distant places, identify and support problem areas, re-create local landscapes in the real world, make informed political decisions, and better understand the movement of people, ideas, and money—as well as don giant fire-breathing monster avatars and slog through virtual cities. Christopher Columbus, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, Godzilla, and the Mario Brothers would be equally blown away.”

But the book opened with a simpler statement: “Second Life is and always will be a representation of the world as we know it. It has been conceived by and is being created by humans, and people tend to do things in a certain way. It doesn’t matter whether the world they’re in is virtual or ‘real.’ … All these banal truths become even more true in Second Life. It lets you concentrate single-mindedly on the pursuit of your own, private happiness.”

Second Life never blew away the Mario Brothers. But in a way Second Life is and always was what it claimed to be: a digital environment for users to do whatever they want to do within it. It just took a while to figure out what that was.

Mark is an editor and columnist at Cracked, a regular contributor to Macaulay Culkin’s Bunny Ears, and has written a novel you can check out here.