It’s rare to witness the birth of a new genre in games. Reinventions and resurgences are common—true originality, less so. Yet over the past five years, we’ve seen a fascinating new type of game emerge, to both mainstream and critical success, across a spectrum of titles that seem to defy easy classification. Exemplars like Return of the Obra Dinn, Outer Wilds, Heaven’s Vault, and Her Story may differ in setting, theme, and even some aspects of gameplay, but anyone who’s played them will recognize a common thread. Still, how do you link together a time-hopping insurance assessor, an alien explorer, an archaeologist and her robot, and a nameless investigator? Last year, game designer Tom Francis did just that when he coined a new term: information games.

In his design talk on the subject, Francis describes the genre as one where the player’s goal is to acquire information, but also to use that information to create new theories, which players can then use to go in search of even more information. In many ways, these games can be considered a direct reaction to the heavily defined and gamified role that information plays in the detective and puzzle genres. Rather than telling you, “This is an important clue,” or, “This is how a detective sees the world,” they instead focus on the self-determination of your own reasoning. As Francis explains in his video, “It’s using the real world, the kind of skills you would use if you really were a detective.”

This was the goal of Sam Barlow’s Her Story, not just a new breed of detective game, but a response to what Barlow saw as a tendency among big detective games to railroad players, stumbling over the challenge of making mechanics out of solving crimes. It is also undoubtedly the first information game, uniting a wide array of influences—including Portal, Phoenix Wright, the riddle books of Kit Williams, and detective TV shows such as Homicide and Cracker—into something novel. In Her Story you are charged with piecing together the circumstances of a murder by searching for video clips in a police database. By searching for keywords and watching the resulting clips, you gradually discern the underlying truth of the mystery.

Credit: Sam Barlow

“Really the starting point for Her Story was the decision to focus on the interrogation room (and process), using that narrow constraint to fuel the game,” Barlow told me. “I spent over half the development time on paper—first researching the idea intensely, then reading police textbooks, academic studies, real-life interview transcripts, and watching recordings of interviews.”

Barlow described building a prototype that relied on a series of transcripts from a real-world criminal investigation. Even though the transcripts were entirely organic rather than the work of a game designer, navigating them by searching felt “structured,” he said. “I picked up on hints, I made deductions, I followed threads in the story. That was a huge moment, because the way that made me feel was like nothing I’d experienced in another game. The combination of freedom and deduction and exploration was really something. That was when I decided I’d do something similar—I wouldn’t design, or enforce a path through the game, I’d create something organic, rich, and layered and trust that from that, each player would create their own interesting journey.”

Eventually, Barlow shifted how he would frame the game’s story: The player wouldn’t be a detective trying to solve the case, but a third party diving into the interviews well after the fact. “That immediately opened the game up to be non-linear, and with the cold-case angle it really emphasised the sorting-through, the mining for information, and putting the jigsaw together,” Barlow said.

This idea of a third party highlights a unique way many information games position the player. Often, as in Her Story, the character essentially acts as an interface, allowing players to personally invest and create their own narrative of discovery. Your searches and deductions reflect a self-determination. As Francis notes in his video, that’s an important point of distinction between information games and traditional puzzle games: You’re not making “a guess about what the designer was thinking.” These theories, discoveries, and narrative beats gain power because you divined them. That determination also ties into a freedom of approach, what Barlow called the “non-linear,” as players are pushed to pursue their own instincts and follow pathways the designer may not have intended.

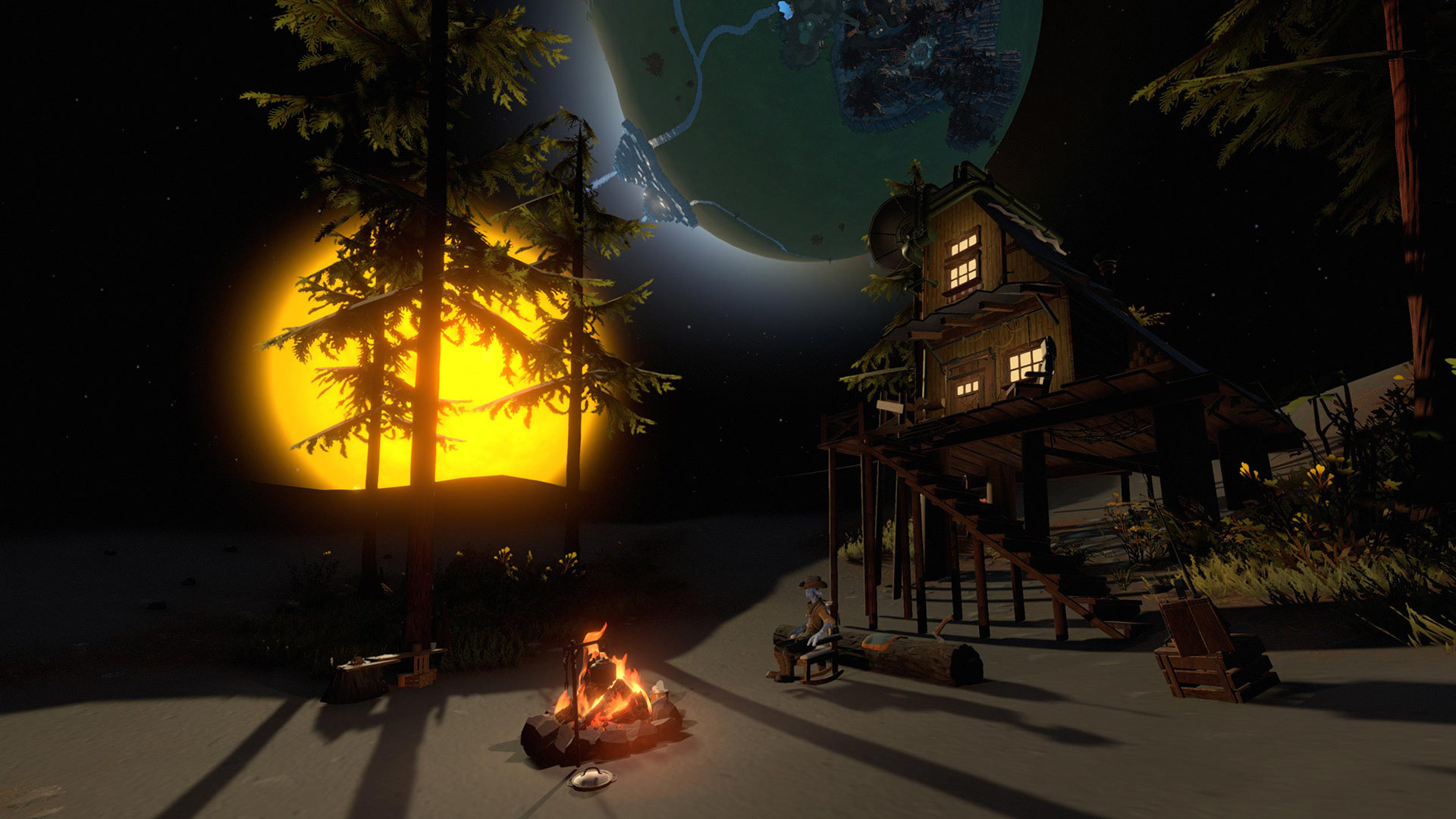

Few games channel that sense of freedom better than Outer Wilds, with its mysterious playground of planets and lost Nomai ruins. “We like to joke that Outer Wilds is about tricking people into doing science,” Loan Verneau, creative lead at Mobius Digital, told me. “What we mean by that is we let people come up with their own hypothesis and then test those hypotheses. One of the great things about doing and learning about science is how it changes the way you look at the world.”

By placing players on a repeating 22-minute loop, Outer Wilds dares them to imagine, to develop new theories to test in its often dangerous world. Death, however, merely resets the loop—allowing the player to start over with whatever new information they’ve obtained. As with Her Story, the discoveries are non-linear, echoing that same freedom to investigate whatever lead you wish. It provides a playful sense of exploration which is easy to appreciate when you consider the game’s goal, as Verneau described, of merging a backpacking aesthetic with realistic spaceflight.

Credit: Annapurna Interactive, Mobius Digital

But this junction of high-tech and low-tech is just one of several dualities Outer Wilds explores. “The game aesthetic was always one reminiscent of the fall season. This is the end of things but there is a great beauty to the world at this point in time,” Verneau said. Like fall, Outer Wilds balances on a precipice of both life and death, warmth and cold, hearth and loneliness. The system lives, but beneath its surface lies the ruins and remnants of those long-gone.

That final point in particular is worth noting, because information games commonly call to mind the practice of archaeology. For information to be exposed, one presumes, it must first have been buried. Every information game features a special method of uncovering knowledge. In Her Story it’s the search terms; in Return of the Obra Dinn, the Memento Mori, a pocket watch that lets you revisit scenes from the past. But both Outer Wilds and Heaven’s Vault utilize the trope of discovering history in more straightforward ways.

“Archaeology has been in games for a long time. Environmental storytelling is detective work, it’s about reading clues; archaeology is the same process, only for places that are significantly more ancient,” Heaven’s Vault co-creator Jon Ingold said. “The main innovation that I see, both in Outer Wilds and Heaven’s Vault, is that the information you figure out from reading the environment isn’t just color, but core: You need it to be able to progress. We recently had a review from Heaven’s Vault by an archaeologist, who described it as a game about traces, and I loved that. It’s about uncovering traces, marks, lost signs and trying to bring them to life and give them meaning.”

Credit: Inkle

This act of bringing lost signs back to life is, of course, historical translation. Outer Wilds gives players a tool that nearly instantly translates the ancient Nomai language, but the act of extracting information in Heaven’s Vault is a far greater ordeal. With the help of archaeologist Aliya Elasra and her robot Six, players traverse the Nebula, uncovering and solving a series of complex translation puzzles. For each, you must select meanings for sections of individual phrases, gradually building a vocabulary through trial-and-error as well as experiments in usage and context. But this arduous path to true meaning reflects the games’ historical context best of all.

“History is a mess, and to make deductions about history is always unsafe,” Ingold said. “We wanted to get away from the idea that history is a ‘puzzle to be solved,’ rather than a mass of stories to be unravelled, retold, and reconsidered from one generation to the next. Heaven’s Vault has 5,000 years’ worth of history to discover, full of murders, revolutions, uprising, falls, rises and re-emergences. Everything you discover should lead to more questions, more discoveries. And none of it is static—it’s all fueled by the player’s explorations, their translations, and the elements of the game world they connect together.”

The beauty of Heaven’s Vault lies in a world where everything exists as part of a larger connected context—symbols within words, words within sentences, and, in the same way, humans within history. Translation relies on the inherently contextual meaning of language. Change a single word, and the whole shifts.

Credit: Annapurna Interactive, Mobius Digital; Inkle

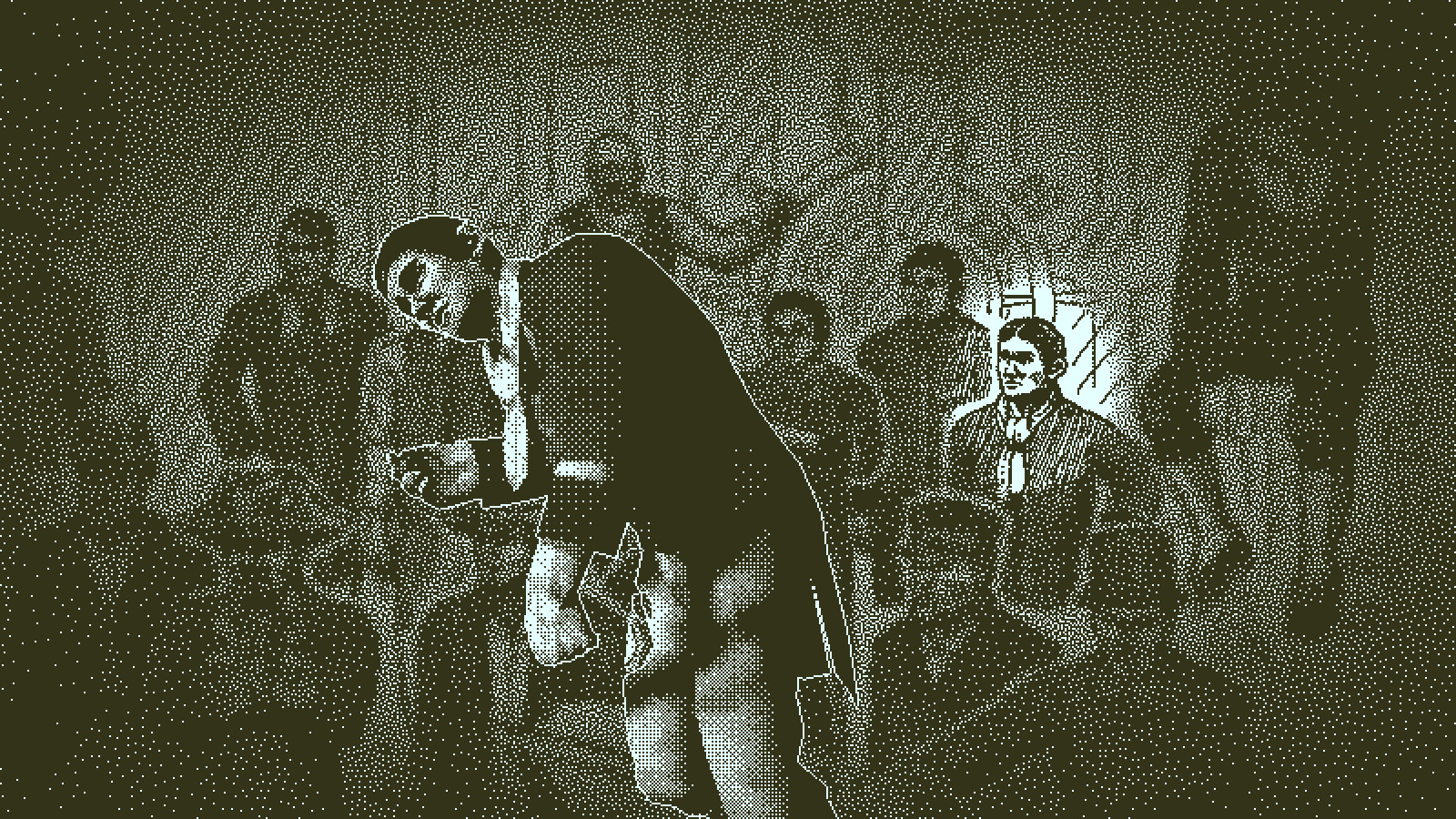

It is the same for Return of the Obra Dinn. As an insurance assessor, you are charged to uncover the fates of 60 souls, tragically lost on a sea voyage, each consisting of a name, a cause of death, and a killer. Because you have access to a list of names, matching fates to the people you see in each scene directly contributes to identifying the others. “The fact that the game uses a process of elimination is, I think, a reason that the deduction is as open as it is,” creator Lucas Pope said.

But just as this openness is important, so to is the game’s restriction. As Sam Barlow explains of restriction: “The only way to let players feel free and give them a possibility space that is fun to explore is to impose some bounds, a limitation, the structure within which they get to play. More ambitious games have lots of systems and lots of smaller restrictions (you can shoot this, but not this; you can climb this wall, but not this wall; you can open this door, but not that door). But I think if you say ‘no, focus everything on this, and here’s its constraint’, it feels liberating.”

What makes Return of the Obra Dinn so special is this paradoxical freedom born of limitation. Using the Memento Mori to see a soul’s final moments creates a restricted gameplay loop, but at the same time you can wander the ship, accessing any memories you’ve unlocked in the order you choose. It provides both an open world of information and a focused means of engaging with it. But it also represents restriction as an aspect of solo development. “When it comes to making games, in most cases I’m working with such limited resources that it’s important for me to try to do things differently from other games, so I’m not competing with them directly,” Pope explained. “I don’t have the resources to make the same kinds of things that larger teams can.”

Credit: Lucas Pope

Her Story channels a similar balance of restriction and openness: an entire database of clips, yet only access to five at a time, limited by the search terms you use to find them.

Despite their freedom, restriction is a surprisingly important element of information games. For example, Obra Dinn will only confirm whether your deductions are correct in batches, once you’ve identified the names, causes of death, and killers of three crew members.

“The system was originally designed explicitly to prevent cheating,” Pope said. “I learned from Papers, Please that immediate feedback for player performance is important, and I wanted something similar for Obra Dinn. Unfortunately, marking fates correct as they were entered couldn’t work because it’d be too tempting to cheat, even for honest players.”

Heaven’s Vault also uses a similar system, removing an incorrect word-meaning after it has had the chance to cause a failed deduction. “This kind of balancing is always a trade-off between false positives and false negatives,” Ingold said. “No validation, and players quickly feel swamped and overwhelmed, and they throw the game away as impossible. Too much validation, and player’s feel they’re ‘supposed’ to get every translation right; and worse, that they can and should brute-force every problem until they get it right. All information games strike this balance between what you confirm and what you hold back, and I think it’s one of the things that’s fascinating about them.”

Despite the many variations that exist between them, what unites these games is that player-driven sense of curiosity and how it’s utilized as a game element. More than almost any other genre, information games are incomplete without the player. The curiosity and wonder that each of us carries within ourselves is their driving force.

For Lucas Pope, that wonder came from the Mac Plus games he played when he was a kid, for which Obra Dinn became “a visual ode.” For Outer Wilds it’s science and discovery—as Verneau said, “We wanted players to explore because they were curious about the world.” In Heaven’s Vault, Jon Ingold finds wonder in the guesswork of history, the tension between tangible truths and “mysteries that delight us.” And for Sam Barlow, it comes down to the trust that he, as a designer, places in the player. Because that’s the real origin of information games: freedom born of trust.

“How do we allow an invested player to reveal story in a way that is personal?” Barlow asked. “By understanding that this in itself is the reward.”

Header image credit: Return of the Obra Dinn, Lucas Pope

Sean Martin is a poet and game journalist living in the South West of the UK. He has written for Wireframe, Eurogamer, PCGamer, PCGamesN + many others. He writes about varied subject matter, from climate change to rat representations in games. You can find him rambling about anime and Total War on Twitter @LoreScavM.