“Pancake games” is a term used frequently among virtual reality aficionados to refers to non-VR titles. Like “walking simulators”—a term mocking that genre’s perceived lack of interactivity—the phrase originally carried a slightly derogatory tone, pointing to the VR community’s burgeoning fatigue with traditional video games. But it was also born out of sheer convenience, as a means of easily capturing the essence of what games that aren’t on VR, augmented reality, or mixed reality platforms lack. Plus, it’s just plain amusing to think of these games as soft, floppy pancakes.

“I likely saw it on Twitter first (as short-hand nomenclature tends to occur a lot on character-limited messaging). I’ve seen a decent number of VR peeps use it. ‘Flat games’ is sometimes used. ‘Pancake’ is just more fun,” Anton Hand, the CTO of creative studio RUST LTD, told me.

Credit: Sony

But in 2019, the overwhelming majority of games, whether measured by the number of new releases or dollars spent, are still pancakes. Last year, the combined market for VR, AR, and MR gaming brought in $6.6 billion dollars, according to SuperData Research. Over the same period, the game industry as a whole generated nearly $135 billion, per Newzoo. Official sales numbers for VR games and hardware are difficult to come by, but the figures we do have paint a similar picture. In March, Sony announced that it had sold 4.2 million PlayStation VR headsets. As of this summer, the PlayStation 4 has sold more than 100 million units. If virtual reality represents a sea change for gaming, the tide has yet to come in.

Sitting opposite the data is an undeniable and enticing truth: VR has long been about submerging players in an alternative, artificial universe, but it’s only now closing in on the fictionalized versions painted by science fiction stories. Rather than just functioning as platforms for flight simulation or military training—like it had been for the past few decades—modern VR promises a more immersive reality that could revolutionize not just gaming, but also the way we interact with one another. Among the VR developers and experts I spoke to for this piece, there exists a widespread belief that we’re still at the beginning of an industry, not the middle or the end. Virtual reality, they told me, is only going to get more ubiquitous from here.

“Between Star Trek, Black Mirror, and Ready Player One, it’s tough to exist in 2019 and not know what VR is,” said David Jagneaux, senior editor of virtual and augmented reality news site UploadVR. “People see it everywhere now and are curious—it’s about making the impossible possible.”

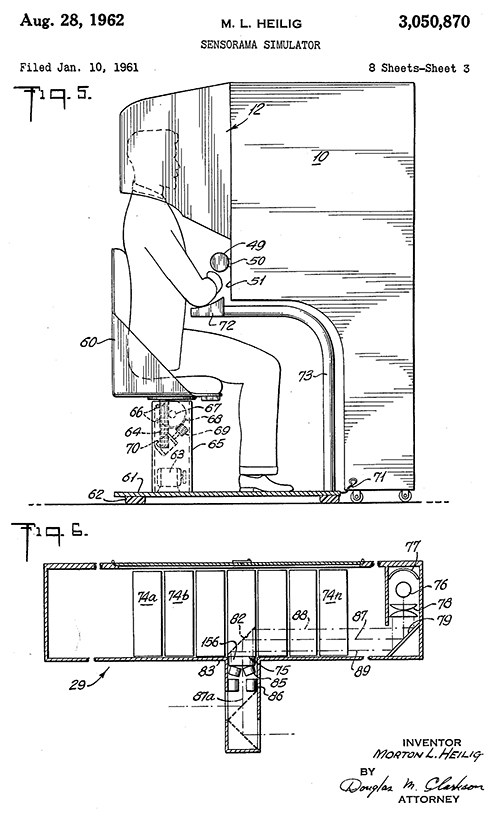

Far from being a recent phenomenon, VR as we know it today has been built upon innovations that date as far back as the 19th century. Some of its rudimentary elements, like stereoscopic images that trick the brain into seeing depth in pictures, existed in the 1860s. Most of what’s fundamental to modern VR can be traced back to designs invented in the 1950s, the most notable of which is filmmaker Morton Heilig’s Sensorama. The Sensorama is a bulky machine that resembles an arcade cabinet, but with an extended display that lets you stick your head inside. While it lacks any conventional interactivity—there are no inputs—users can experience the spectacle of New York City, complete with tactile feedback like smells and winds that are triggered at specific scenes. A few years later, Helig also created—and patented—a head-mounted VR display called the Telesphere Mask.

These inventions weren’t commercial successes, but they paved the way for future VR headsets—like the lofty-sounding Sword of Damocles, developed by Ivan Sutherland in 1966. Between 1970s to 1990s, pioneers like artist David Em with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory began to create navigable virtual worlds. In 1978, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology even developed an interactive map of Aspen, Colorado. The following year, Eric Howlett designed the Large Expanse Extra Perspective (LEEP) system, which was groundbreaking for its rendering of depth and realism, providing the conceptual basis for most VR helmets today. And then there’s Jaron Lanier, often considered to be the founding father of VR, who went on to expand on the field with VPL Research, one of the first companies to develop VR products exclusively.

Despite these strides in progress, VR was far from becoming a household tech. For years, development focused primarily on tools for industrial training in the military, medical, and aviation industries, as well as for designing automobiles and aircraft. It was only in the 1990s that consumer-friendly VR headsets were produced. One such headset was the Sega VR with its head-tracking capabilities, but the device ran into issues of motion sickness and nausea among test groups, and a planned home release was eventually canceled. The Virtuality Group developed its namesake gaming system, complete with headsets, exoskeleton gloves, joysticks and even networked units that allow multiple players to game together. Yet these failed to take off commercially since they were sold for exorbitant prices—Virtuality was priced at an eye-watering £25,000. Interest in VR was piqued but could not be sustained, a tension exacerbated by a 1992 sci-fi film The Lawnmower Man. Featuring VR as a neon cityscape with iridescent avatars, the movie was one of the first instances of VR in mainstream media, setting the public’s expectations of the tech.

Credit: New Line Cinema

One of the more infamous experiments in VR was Nintendo’s Virtual Boy, a clunky console that had to be propped on a flat surface of a specific height (a table, for instance). The brainwave of famed Nintendo developer Gunpei Yokoi, development on the console was rushed due to pressure from then-president Hiroshi Yamauchi, who wanted it released quickly to buy time for the Nintendo 64. This mandate severely reduced the development time for the console, which forced Yokoi’s team to make compromises and resulted in the console being released in an unpolished state. Notoriously panned by critics, the Virtual Boy’s monochromatic red display, high price, and low-quality games doomed it as a commercial failure. While a compelling concept, the console wasn’t given the opportunity to live up to its fullest potential.

Despite these innovations, VR was met with relative indifference throughout the 2000s. It wasn’t until 2010 that the poster boy of modern virtual reality, Palmer Luckey, rejuvenated the conversation with the Oculus Rift’s first prototype. Valve quickly followed up by developing the HTC Vive with Taiwanese consumer electronics company HTC, while Sony released its PlayStation VR in 2014. In 2016, former Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé stated in a Bloomberg interview that Nintendo would consider investing in VR—but only after the company saw widespread, mainstream adoption of the technology.

Such sentiment is why Adarsh Muthappa, the co-founder of VR startup AutoVRse, felt a pressure to develop solid VR indie games. “Gamers expect incredibly polished games from triple-A studios, but no big studio is ready to invest the time and money in VR without indies testing out the medium first. So it is on us indies to produce and release engaging VR titles first. With this comes a certain responsibility to ensure high quality experiences for gamers,” he said. Unlike mobile apps where the worst outcome of poor game design and performance is probably game lag, Muthappa elaborated, motion sickness in poorly designed VR games can result in players growing averse to the platform on a broader level, potentially swearing it off completely.

Eddie Lee, founder of games studio Funktronics Lab, echoed this, adding that the business of VR games already has a “fundamental economic problem.” Making games as a living is already challenging, but players’ sky-high expectations for VR can aggravate the issue. “Modern gamers are conditioned to expect high-quality production values in games, especially core gamers who go to VR to be deeply immersed in the realism of the experience. This usually translates to high-budget productions, which is in direct contention with the very limited VR gaming market. As markets continue to develop and grow this will change, but we are not there yet,” he shared.

Credit: Funktronics Lab

While VR has yet to truly bust through into the mass market, the reveal of a makeshift cardboard VR headset for the Switch this year—the Nintendo Labo VR Kit—is a sign that Nintendo is at least willing to test the waters. Taken with Fils-Aimé’s previous statements, that’s a meaningful endorsement from one of gaming’s most important companies. Meanwhile, triple-A studios like Bethesda and Gearbox have been porting their games to VR, in another indication of the optimism expressed by developers towards the technology.

As a VR veteran who has been dabbling with the technology since 2004, Hand from RUST LTD was particularly awed by what he saw as the massive leap of progress in VR. “I actually think the amount of advancement we’ve seen in the past three years, especially compared to the rest of VR’s history, has been explosive and has been incredibly impressive. I think anyone who isn’t pleased with where we’ve gotten from the Vive’s initial launch to now, doesn’t understand how hardware works and how long it takes these sort of things to work,” he said. “The fact that we went from everything is broken all the time to actually [being able to] plug this stuff in and it just works, in that period of time is rather impressive.”

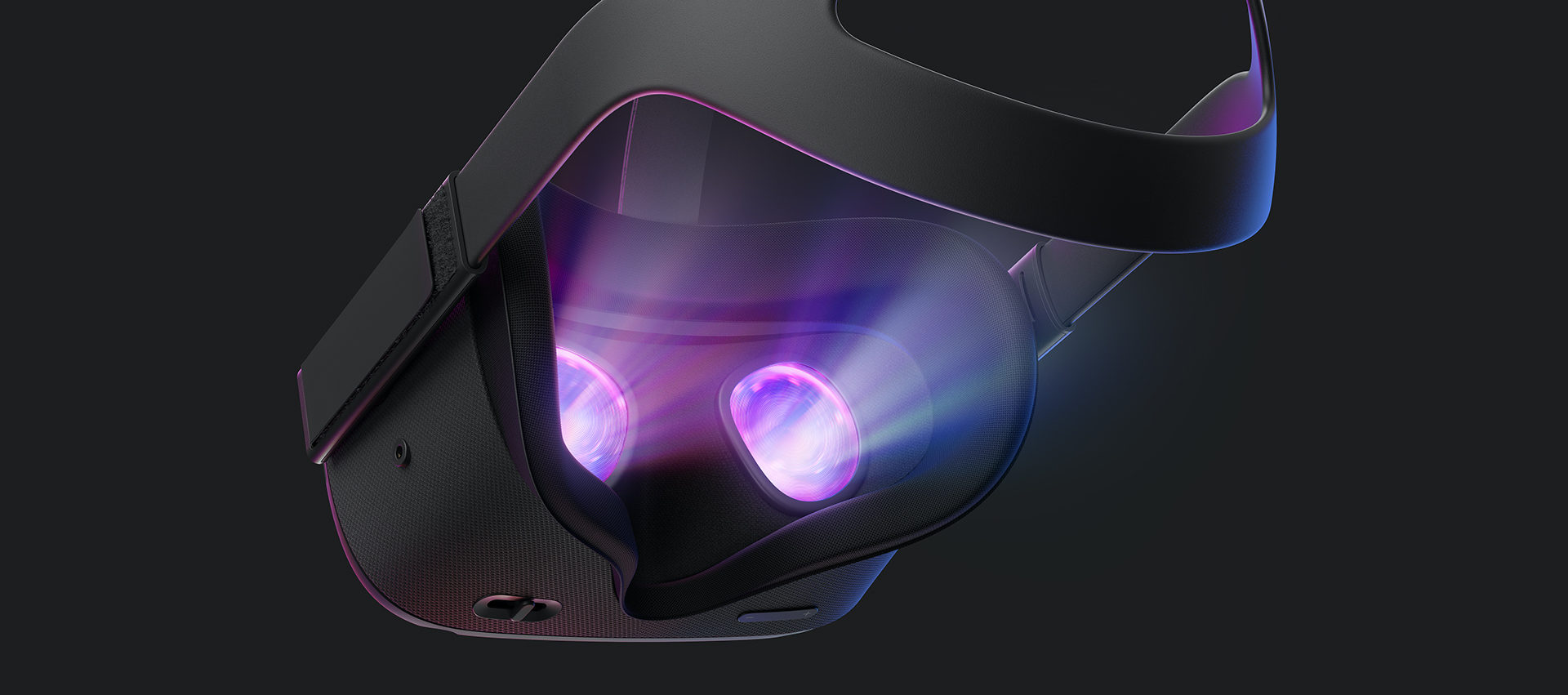

An example of this breakthrough is the pace of new innovations in VR. Take for instance the Oculus Quest. It’s an untethered, all-in-one VR headset—all you need is to put the headset on, without any additional equipment to experience its VR games. Such advances seemed unimaginable just a mere decade ago. “Now, we have the Oculus Quest, a full 6-DOF standalone system at $399. Who could have thought we would achieve all this in such a short period? As a game developer who’s used to console cycles of six years, seeing the scene evolve at such blazing speeds is extremely exciting, but also very bewildering!” Lee said. And with Oculus Quest offered at this relatively affordable price, it isn’t such a stretch to expect that VR headsets will only become cheaper, while with performance that allows games to be both immersive and responsive.

Credit: Oculus

Hampering some of the enthusiasm for VR, however, are the latent issues the platform faces. In its current state, virtual reality still isn’t too consumer-friendly. Jagneaux, for instance, told me of his hesitancy to recommend the HTC Vive or Oculus Rift to his friends, given the complex setup required. In the same vein, Ana Valens, a freelance reporter who regularly covers VR news, suggested VR requires some finesse and skill to properly set up while some kinks are still being ironed out by manufacturers. “I recently received an Acer Windows Mixed Reality headset for work, and it took some time to set up: I had to plug in the right cables to the right USB ports for my graphics card, make sure my room had enough space to use my controllers freely, position myself in the best manner possible for unconstricted flow (so I don’t slam my fist into my monitor), and then learn both the Windows Mixed Reality interface as well as SteamVR’s. I also had to troubleshoot some issues getting the latter started,” she added.

Despite a decades-long legacy as a technology for enterprise use, modern VR as a gaming platform is rather nascent, so these inconveniences are to be expected on some level. Given the medium’s relatively short history with gaming, most developers interviewed for this piece faced common challenges around navigating VR gaming mechanics that have yet to be established. Imagine, for instance, a red line that floats on top of an enemy’s head in a game. In a pancake game, most players would instinctively see this as a health bar that will become shorter as the enemy is being bludgeoned to death. It’s a convenient, familiar shorthand that makes it easy to communicate crucial gameplay information. But in VR experiences, any non-diegetic interface—that is, elements that are not part of the in-game universe—may impede the immersion that’s so important to players. The old solutions won’t always work.

Hand explained why such seemingly simple issues can become so multifaceted for VR designers, raising the need to display the player character’s health as an example. “On a pancake game, [we can put a bar in the] lower left hand corner that isn’t going to disrupt other elements of play. In VR there is no obvious thing. Attaching UI elements to the head is infuriating. It almost feels you’ve got a bug that’s always stuck there. Putting it on the hand can be an issue because it can either intersect or obstruct something you’re holding, or not be visible when you have your hands down at your sides.”

Credit: PsychicParrot

Jeff W. Murray, who developed the VR game Axe Throw VR, offered a similar outlook. “The rules on ‘interactions that make sense in VR’ haven’t really been written yet, so we’re all sort of feeling our way around menus and game interactions to see what works and what doesn’t. We can fall back on a lot of game mechanics, like leveling up or unlock systems etc. but it’s how we interact with those systems that’s unique to VR.”

One idea Murray had is to seamlessly adopt the habits we have from the real world in VR. “When we go into VR, we take with us a whole bunch of expectations and conventions from both gaming and the way we interact with the real world. Finding ways to represent those conventions or work around them or to give them context so that your world makes sense requires more than just making it look good, or making it sound good or making the controls work—you need all of those and then some relationship to real-world action.”

There is also a litany of other challenges, from minor annoyances that offer unique challenges to VR game development, to bigger concerns that impede mass marketing adoption. Haptic resistance, or issues with touch sensations, is one concern, as pointed out by Nima Zeighami from Agency XR. Another is that most VR headsets today are tethered, which leave users extremely prone to accidents. “Having to constantly avoid tripping over a wire and being restricted to a short distance away from a PC or game system is severely restricting,” said Jagneaux. “There also isn’t a good, universal form factor yet. Some people prefer the halo design of the PlayStation VR and Oculus RIft S, while others prefer the more common headset style of the Vive, Index, and original RIft.”

Others suggested that movement in VR is another point of contention, since there hasn’t been any real design need to innovate alternative approaches in pancake gaming. Ken Thain, senior VR producer of studio Archiact VR, said he feels the physical constraints inherent in VR means new methods of traversal must be developed. “We started development with this challenge in mind for our most recent VR game, Freediver: Triton Down, where swimming is the way you move in the world. We were able to create a very unique and innovative experience when facing this movement problem up front. But between swimming and zero-G, your movement options that just involve your hands become limited,” he added.

Credit: Archiact VR

Even though VR’s tech still isn’t as prevalent as devices like smartphones and tablets today—or even standard gaming consoles—there’s plenty of enthusiasm surrounding the medium. Some developers believe VR headsets and systems will become an integral part of the household in as soon as a decade. Others believe that VR will mostly remain the plaything of the niche, “core gamer” market. “I see VR being commonplace in all technical workplaces, and even in retail and showrooms. I see it being a large chunk of the niche ‘hardcore gamer’ market. I see it being a sizeable but small chunk of the greater entertainment landscape, still behind movies and television and not as big as traditional games yet, but getting closer year over year,” Zeighami said.

As journalists, Valens and Jagneaux even see lots of potential for virtual reality in esports and streaming circles. “I think there is great potential for many of those trends to be leveraged as long as they’re adapted accordingly. The VR League is doing a good job of making active VR games like Onward, Echo VR, and others exciting to watch competitively. Streaming is tricky because 2D screens can’t accurately convey what it’s like inside VR, but we try our best at UploadVR!” Jagneaux said.

Lee summed up the sentiments of those I spoke to most succinctly: “Even though VR has not really blown up as we all expected it would, I still feel very fortunate to be a part of this industry, and am very excited and hopeful for the future.”

In this, he is hardly alone. From its origins in speculative fiction and early innovations to its recent resurgence, VR has always been defined in the popular imagination by a hope for the future. Whether that immersive, fantastical vision of tomorrow will ever become our present remains uncertain—but that won’t stop creators and tinkerers from toiling to make it a reality.

Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity.

Header image: Harsimran Sain for EGM

Khee Hoon Chan is a freelance writer and copywriter from Singapore. She has written for Unwinnable, Rock Paper Shotgun, Polygon and other fine publications.