I found myself at a standstill.

I’d been asked to write on the ways climbing is depicted in games for the new EGM, but I couldn’t find the correct approach. I thought first of writing about how the belay system used by climbers—especially free climbers like those seen in the documentary Dawn Wall, who have to perfectly complete a sequence between two fixed points before moving to the next “level”—could very well have been a blueprint for early game designers breaking games into sequences. Or perhaps a story writing about the evolution of climbing in games from the two dimensional Donkey Kong to the virtual-reality world of The Climb. Good ideas, but I discarded both—the former interesting but too brief, the latter too pedantic and lengthy.

It wasn’t until I was hired in January to write a separate piece about Free Solo, the popular and Academy Award–winning documentary covering Alex Honnold’s ropeless four-hour ascent up the 3,000 feet of El Capitan, and its possible effects on climbing culture for Blue Ridge Outdoors Magazine that an angle occurred to me.

And it would lead me to one of the most tragic events I am ever likely to cover as a journalist.

Climbers use extensive safety equipment to protect them on their ascents. They hammer in bolts, work with partners, and spend much of their time managing their risk. The vast majority of games that depict climbing do not bother with such tediousness; that would slow down gameplay.

The free solo climber is similarly unencumbered by safety measures. They are free to focus on the primary task at hand: to ascend and to not fall.

Credit: Sony

Climbing in games is an exercise, albeit an exaggerated one, in virtual free soloing. Looking at the virtual free soloing of in-game climbing through the eyes of real-world free soloist would offer not only a unique view into gaming, but also a unique view into the mind of a free soloist.

I needed a free soloist for both articles, but with free soloing being one of the most taboo, dangerous, and controversial styles of climbing—and because free soloists are typically loners and hard to find in general (and very unlikely to go on the record for an interview)—finding one as a primary source is no easy task.

But I was lucky.

In February I was introduced to a free soloist, one of the most avid and underground practitioners in that forbidden art. And he was available and interested in being my primary source for both the outdoor climbing article and the piece for EGM.

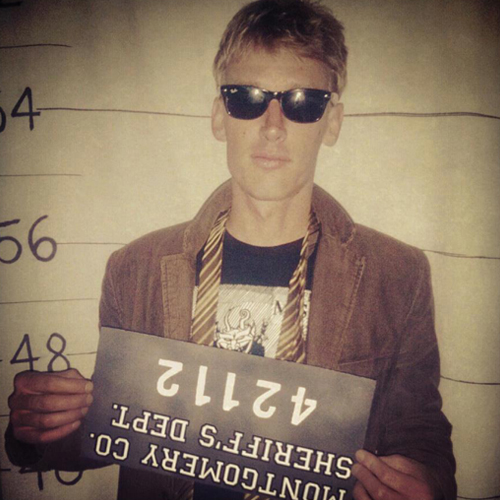

His name was Austin Howell. He was 31, and on June 30th, two weeks after I had completed the last in a series of lengthy interviews with him, he fell 80 feet to his death.

Filmmaker Adam Nawroot was the first to recommend that I interview Howell. Nawroot specializes in outdoor photography, and we were discussing Jimmy Chin, the producer and primary videographer of Free Solo. We talked about the inherent worry of how, if Honnold fell, it would be emotionally devastating to members of the filming crew who’d witness him “fall out of frame.”

When I asked Nawroot if he knew of any free soloists that might go on the record, he did not hesitate. “Have you heard of Austin Howell?”

I found Howell on Facebook and sent him a message. While awaiting his reply, I brought him up to other climbers I interviewed the following day.

One responded: “That guy is going to die for sure. He’s out there. I think most people feel that way. He’s got a reputation like that in the climbing community. He’s not all there.”

from his YouTube channel.

Another: “Austin seems to be putting on a show for people. Shock value is his value.… I hope the dude doesn’t wipe out, and on camera. That would suck.”

I read everything I could find about Howell online: his interviews in magazines and on podcasts, the responses to his YouTube channel, his website that anticipated an upcoming documentary about him.

He had been free soloing for years, mounting cameras to the base of rock faces to document his ascents. Recently, he began using drones to better capture the size and scope of his climbs. I read about his affinity for John Muir, John Bachar, and Mike Reardon, and his belief that part of the vibe of free soloing was the solo aspect, a sort of spiritual oneness that comes when one is alone on a rock face.

I thought his fellow climbers may be jealous of his recent fanfare, judging him as indulging in vainglory in a style of climbing that, up until Free Solo, had been mostly hidden from public view.

I decided to proceed with Howell as my primary source, and we set up our first phone interview the following weekend.

It was apparent from our first phone conversation that Austin Howell was a well-spoken, well-versed, and thoughtful young man. We scheduled the interview to coincide with a five-hour drive from his home in Chicago to the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, where he would spend the weekend scouting out free solo ascents.

After introductions, and before I asked a question, he jumped right in:

“Soloing, in one way, is the most obvious way in the universe. The known written history of climbing in the United States began with John Muir in 1888 climbing Cathedral Peak at El Capitan. The carabiner and the piton didn’t come around until [decades later]. Essentially he free soloed that cliff to the top of it, and free soloed it back down. We’ve got Pueblo people a thousand years ago making these houses in the rocks without carabiners and belay systems.”

Credit: Ubisoft

It was dusk, and I was sitting at a table on a covered back patio watching the flashes of lightning accompanied by the rumbles of a spring thunderstorm. Howell was in heavy traffic and would break up the conversation by talking about how his new truck had an automatic transmission, how times like now he missed his old manual. When my internet connection flickered and I had to restart the recording, he joked that he felt his colleagues had not done a good job—he had previously worked climbing and maintaining telecommunications towers at 300 feet, exposed to the elements.

We revisited that part of his past in another interview, while discussing the Notre Dame climbing sequence in Assassin’s Creed Unity.

Howell related Arno Dorian walking beside the cathedral looking for the best ascension of the tower to himself walking modern day city streets with fellow climbers. It reminded him of Alain Robert, the 56-year-old free soloist known as the “French Spiderman,” who is renowned for climbing city structures such as the Eiffel Tower and the Sydney Opera House but has never attempted Notre Dame.

“We’re always looking at these little gaps in the brick and mortar, wondering where we can dig our fingers into holds and make a way up,” Howell said.

That first night, for hours, we spoke through the thunderstorms about all sorts of climbing, and what led him to free soloing.

He was the kid that climbed the tallest tree in hide-and-seek, never to be found. He took up rock climbing at an indoor gym in college, and a coach there encouraged his natural ability. He won an expensive rope and some safety gear at an outdoor climbing competition at a county fair in his home state of Texas, a prize he says changed his life. After transitioning to outdoor climbing, he continued to excel. Using his new rope, he acquired the necessary requirements to become a lead climber—in a shorter amount of time than most. Climbing lead requires you to go long stretches between safety bolts, attaching ropes for fellow climbers. If you fall, you drop a distance equal to the slack in your line to the previously attached bolt, which can be upwards of 30 feet. Even with safety measures, lead climbing carries a significant risk of injury. Howell thrived under the pressure.

in a still from his Vimeo channel.

He didn’t call it an epiphany, the first time he’d released himself from the ropes. He’d been halfway up a steep rock face and felt weighted down by the heavy bag of bolts on his back and the ropes on his shoulder. He’d simply unhooked himself and passed the gear to his climbing partner. To most this would seem an act of lunacy, a death wish. For Howell, it was natural and freeing. He had been climbing for two years, and he spent the next 10 climbing primarily as a free soloist.

He completed hundreds of free solo ascents across the country. We discussed how he filmed his climbs and began posting the videos on YouTube. One of his videos, documenting a free solo ascent completely naked save for a hat, made it onto MTV’s Ridiculousness. With the growing attention being paid to free soloists after Free Solo, he had began to attract a larger following within the booming danger-sport landscape, alongside the skyscraper parkour and perilous selfies taken atop towers and on cliff edges.

He spoke with confidence: “When the rope is off you can’t afford to slip. People talk about soloing as if it is one mistake, one slip, and you die. But really, that is so evidently false to be laughable. Except if you pick the wrong route, ideally you should be able to reel that in and recover.”

Route selection is everything with free soloing. In another conversation, this time on a recorded video call, I showed him video clips of The Climb, a virtual reality climbing game developed by Crytek for the Oculus Rift. He felt the developers were onto something with their attention to the problem-solving nature of climbing.

Credit: Crytek

“This looks like a legitimate rock climb because these movements are physically possible, unlike [other games] where there are those wild jumps that are just not physically possible.” I could see his pet bird climbing in and out of his shirt and flying free in his Chicago apartment.

“The Climb does have a few big jumps in it, but I could imagine a competition climber making those jumps. They are in the realm of human possibility.”

When I pressed him about whether he was born fearless, he denied the premise of the question. He said he was not fearless. That he planned routes to avoid being in situations that would cause fear or panic. That fear led to a flow of adrenaline that ultimately caused you to make poor decisions that got you into trouble.

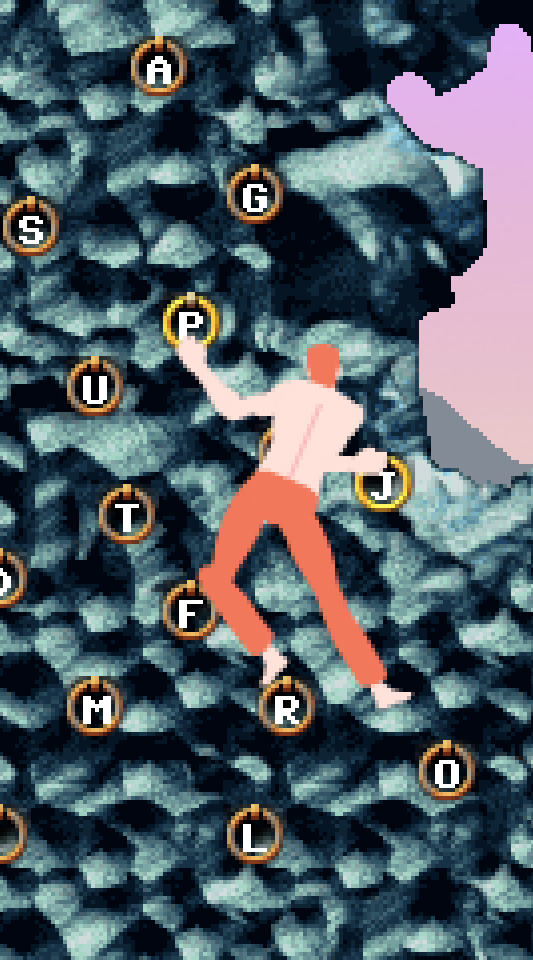

The last game Howell and I spoke about was Bennet Foddy’s Flash game GIRP, in which players use the letters on the keyboard to climb a two-dimensional cliff over water. What this game lacks in visual realism it makes up for with a realistic dynamic swinging motion, which Howell believed to be one of the best displays of climbing mechanics he saw in any of the games we looked at together, only surpassed by The Climb.

When the climber falls from the cliff in GIRP, he splashes safely in the water.

While playing GIRP, Howell spoke of his hero Michael Reardon, a free soloist who perished falling into the ocean in 2007 during an ascent of a seaside cliff in Ireland. Reardon, the ominous master that Howell never met, fell into the chilly water and was never seen again, swept away by a rogue wave.

Credit: Bennet Foddy

Howell told me he had incorporated Reardon’s “smell test” when selecting routes: If an ascent contains high-risk sections that would require an extraordinary effort to overcome, the ascent “smells” bad—it’s not one a climber is meant to free solo.

Perhaps Austin Howell misread the smell test when planning his route at North Carolina’s Linville Gorge June 30th.

I learned of his death two days later as I was spell checking the final draft of Blue Ridge Outdoors article. I had Googled the name of the gorge, since it was the site of Howell’s first free solo climb. The top search result read, “31-year-old free climber falls to his death at Linville Gorge.”

I cannot describe the emotion reading that invoked in me, writing this just a week later. It is too soon to put into words.

I recall Howell complimenting some of the games’ attention to detail in how they depicted unforeseen insects scurrying around handholds and birds coming out of nowhere and offering surprise. Unknown factors like these, he said, are terrifying to a free soloist. Eighty feet up on that summer day, it will forever remain a mystery what caused his hard, long fall.

Two weeks prior, I’d been enjoying a cool drink in a comfortable chair beside a swimming pool, my laptop open on a table underneath the shade of a tall umbrella. I received an email from the lead designer of The Climb at Crytek, and the idea had occurred to me that Howell could offer valuable input for future iterations of the game. It was the weekend, and I knew Howell would be preparing for his next climb. We had talked about working together on other projects, so I called him out of the blue on Facebook video chat. He answered.

I had to adjust my laptop screen from the glare of the pool, a hundred golden alien glowworms shimmering about its surface in the sort of beautiful reflection writers, painters, and game designers struggle to capture.

I told him the articles were coming together nicely, and we joked about Crytek flying him to Berlin to pick his brain. I told him how I wanted to travel to New York to track down Bennet Foddy and said he should come with me to ask Foddy how he’d so well captured the “swinging dynamic” Howell had praised extensively.

The radiating heat had quieted the morning chatters of the sparrows and larks, all surely resting now in the shade of the surrounding dogwoods and lilac trees.

The serenity of the moment drew a stark contrast with the first time we spoke, during that dusk storm, when the thunderclaps rumbled through the Appalachian ridges surrounding me so loudly that Howell could hear them through the phone as he drove to his next climb, causing him to pause and ask me, “Are you sure now is a good time?”

Today was different. It was clear skies, what aviators describe as CAVU—ceiling and visibility unlimited—the best forecast for pilots and climbers and all those who yearn to spend every waking second outdoors, looking out from the vantage gained only from a great ascent.

My girlfriend joined me while we were talking. She’s a better writer than I am and had been helping me get my climbing articles together, and she wanted to talk with him too. He waved to her on the camera. After our long conversations, it was as if I was introducing her to an old friend.

They talked about his fianceé, and it turned out one of the songs Howell listened to before a climb was on my girlfriend’s playlist. She had lived in Chicago, and they talked about the city. They hit it off while I sat back and listened to them talk. I winked at the camera and requested he not flirt with my girlfriend while I went inside to make another cool drink.

We joked and laughed about my tendency to be long-winded during interviews. For a couple of hours that hot day, as he packed his bags and I periodically adjusted the umbrella to keep the shade, we didn’t talk about video games. We didn’t talk about climbing at all.

Header image: Austin Howell free solos at Kentucky’s Red River Gorge in a still from his YouTube channel.

Hart Fowler is the former publisher of 16 Blocks Arts and Culture magazine. He currently works as an independent journalist for both national and regional magazines. He recently has been writing about the opioid crisis, war veterans, art, podcasting, and outdoor recreational sports. His recent collaborative efforts in short-form fiction are currently in the works to be published in both print and podcast form. You can see some of his work at hartfowler.com. Follow him on Twitter @JHartFowler.