On February 11th, a leaflet from the U.K. charity English Heritage was photographed and posted on Twitter to some controversy. The leaflet showed a games controller being speared by a sword, with the caption “Isn’t it time we make their virtual world history?”

Fast-forward to today and this question seems even less laudable than it did at the time, with the virtual world of video games acting as an important sanctuary in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to speculate that tweets and screenshots of Animal Crossing: New Horizons will be historical sources for understanding the experience of people self-isolating during this crisis.

After the online backlash to the leaflet, English Heritage was quick to step back from its marketing campaign. “We’re sorry for missing the mark on this one. This was intended to be a tongue-in-cheek take on a debate among parents, who this leaflet is aimed at. We certainly didn’t intend to dismiss the value of digital culture but appreciate how it came across.” The leaflet seems even more incongruous when you consider that English Heritage has hosted Minecraft workshops and a VR reconstruction of St. Augustine’s Abbey, one of the more than 400 historic sites the organization manages and promotes.

Perhaps this all seems like a storm in a middle-class teacup, but that’s precisely why it deserves a closer look: English Heritage aimed its marketing not just at parents, but middle class parents specifically—those that have greater financial access to both heritage tourism and video games.

It’s to English Heritage’s credit that it swiftly apologized. (At the time of writing, the charity has not responded to an interview request). As Conor Clarke, marketing and communications manager for the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, put it, “English Heritage responded brilliantly to it. I have since arranged for their team to come and visit our museum for a tour. Hopefully we can work together on something in the future.”

I got in touch with Clarke after seeing his brilliant riposte to the English Heritage leaflet. Via the NVM Twitter account, he posted a pixelated image of a sword and games controller with the tagline “Isn’t it time to start celebrating our virtual history?” Touché.

The English Heritage marketing reflects “a pretty outdated sentiment—that video games are a waste of time, and not seen as educationally or culturally worthwhile,” Clarke said. “This has been contested and challenged for decades now.” The existence of the National Videogame Museum itself is a very tangible argument against trivializing an entire medium. It first opened in Nottingham five years ago, before moving to Sheffield in late 2018. The curatorial team is managed by the British Games Institute (BGI), the game industry’s answer to the British Film Institute (BFI), and hosts a range of interactive exhibitions.

One of the BGI’s trustees, Catriona Wilson, believes that media exaggeration has played a big part in fostering contempt for video games. “In reality, the media has a lot to answer for, in so many areas of modern life,” Wilson said. “Too often, video games and gaming culture are blamed for antisocial or criminal behavior. For some reason it is seen as an easy scapegoat, perhaps because many people have seen gaming as ‘just’ for fun.”

Wilson is the head of University College London’s Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. She was first introduced to the NVM and BGI while working as collections manager at the Guildford Museum. “Guildford has a stellar video game heritage—and future,” Wilson said, “and I had started to develop this as a key collecting focus.” Wilson emphasized the importance of games in both her professional and personal life, as she shares the hobby with her son. “My son has access to screens and gaming, just like he has access to green spaces, playgrounds, museums, castles and libraries.” With the advent of COVID-19, access to digital space has taken on a new significance. In general, Wilson said, she does consider gaming a core aspect of managing her well-being.

The view of video games as hapless pastime is impossible to disentangle from the media’s worn-out stereotype of “the gamer”: young, white, cisgender male, and antisocial. A 2019 report by the Entertainment Software Association stated that 46 percent of gamers are female and 54 percent are male, at least in the United States. (There was no mention of other gender identities). What’s particularly striking is that the people making games in the United Kingdom resemble the stereotype a lot more (though not necessarily the antisocial part). According to a Ukie 2020 Games Industry census, 70 percent of people working in the industry are male, 28 percent female, and 2 percent non-binary. Furthermore, 10 percent are from BAME—a British term for “black, Asian, and minority ethnic”—backgrounds, and 12 percent attended an independent or fee-paying school, the latter being double the national average. To be fair, the U.K. games industry does have a high proportion of LGBTQIA+ workers compared to the national average, but it’s still disproportionately white, male, and middle-class.

Credit: Double Fine Presents

Both Clarke and Wilson think that teaching young people about the richness of video game history is key to its future diversity. Clarke cited his colleague Gina Jackson, who said that the work the NVM and BGI are doing is “out of concern for the future. We want to inspire and educate new kinds of game-makers to make new kinds of games.” Clarke expanded on this point: “If we want videogames to be more diverse and reflective of a number of experiences, and advance it as an art form, then showcasing that diverse history is vital.”

That being said, having the time and money to experience a wide range of video games is a privilege. This is why establishing an artistic canon for video games is a double-edged sword for accessibility. The weight of history can be an inspiration or a gatekeeper. “We would think it very odd for a budding filmmaker or writer or indeed any other creative professional to learn their craft without some reference to past films or novels,” Wilson said. Institutions like the NVM can provide an opportunity for a potential game maker to experience older games first-hand. Clarke cited the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum as other organizations invested in curating video game exhibitions, but admits that there is still work to do to cover a broader range of gaming history.

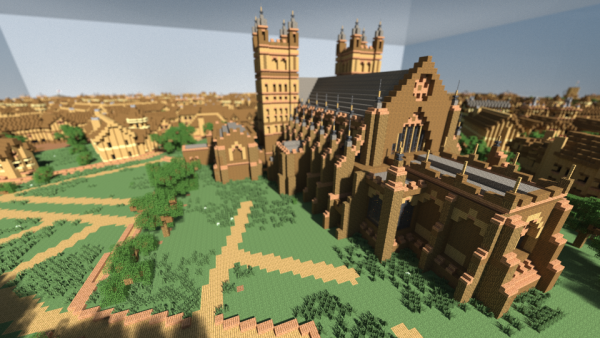

rendition of 18th-century Exeter.

Credit: Microsoft, via RAMM.

It is laudable that the NVM has included local video game heritage in a display called “Made in Sheffield,” which is a reference to the city’s history of steel manufacture. Sheffield steel made its way to the dining tables of stately homes; now stately home visitors take home Sheffield’s games. Just as video games historians and preservationists have aspired to create analogue game museums, traditional heritage institutions like English Heritage have been keen to use games as a hook to draw in wider audiences. As Wilson explains, “Museums like Tullie House and the Royal Albert Memorial Museum have incorporated Minecraft into flagship exhibitions and learning programs that help to introduce a passion for history to new audiences.”

There’s less difference between visiting a stately home and playing a video game than it may appear upon first glance, most notably in how they exist as human-made relics of a specific time and place. Just as demolishing a heritage building would erase a moment in history, failing to preserve video game heritage would create “real risk that this part of our lives would not exist for future generations to understand,” Wilson said.

This risk is now even more apparent with museums like the NVM closing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Currently we’re totally independently funded, with a vast majority of those funds coming from ticket sales,” Clarke explained. “As we’re currently closed to the public due to the Coronavirus outbreak, we are gravely in danger.” The NVM has launched an emergency appeal, as its indefinite closure may soon become permanent if they can’t get funds to cover the core costs that would normally be supported by ticket sales. The loss of the U.K.’s only museum dedicated to video game culture and education would be akin to taking a blade to a rich tapestry; connections lost and loose threads untied.

We need institutions like the NVM to provide space for critical, diverse histories of gaming. Critical histories that acknowledge the disproportionate access that middle-class white men have had to video games are crucial lest we repeat mythologies that cast industry success like pulling a sword from a stone—the purview of “chosen ones.” Respecting video games as an art form requires recognition that they have a history, which is why it was so disappointing to see the English Heritage leaflet’s attempt to jokingly skewer their cultural credibility. However, if we do acknowledge that games have a history, we can imagine that they can and will change, rather than just infantilizing them as a fast food medium of instant gratification. The joystick can be mightier than the sword, and the irony of the English Heritage leaflet is that it has now become part of that which it apparently sought to destroy: video game history.

Header image courtesy National Videogame Museum.

Florence is an archaeologist and freelance games journalist living in London. They do independent research into archaeology and video games. Their Animal Crossing: New Horizons island is called Youtopia and you can either find them there or on Twitter @florencesn.