In the era of Metacritic and lengthy YouTube thinkpieces, it’s easy to assume that negative reviews can have a major impact on a game’s success. We’ve all anticipated a game, perhaps even succumbed to the hype, just to see it get dragged on the internet upon release. The big red number looms mythologically large in the video game marketplace, a crimson bell tolling a game’s death on arrival.

But what really happens when everyone thinks your game sucks?

Poisoning the well

“Developers tend to be of two types from what I’ve seen,” said Mark Lefor, 3D artist for Trials of Ascension: Exile. “Some read every review and let the good and the bad really get to them. The second kind seem to look at the reviews more like data and treat good and bad reviews the same way.”

If negative reviews do emotionally impact a developer, there’s usually a good reason for that.

Credit: Forged Chaos LLC

“Generally teams take it hard largely because of all the hard work they put into it,” said Jeff Lander, whose studio Big Red Button Entertainment developed Sonic Boom: The Rise of Lyric. For a character that runs so fast, Sonic is a franchise that stumbles a lot, especially in 3D. This particular 2014 outing garnered a tragic rating of 32 on Metacritic. GamesMaster put it simply by calling it “possibly the worst blotch on Sonic’s record,” while Eurogamer was a bit less gentle. “It pains me to say it,” Dan Whitehead wrote, “but Sonic Boom needs to be the last noise we hear from the blue hedgehog for a very long time.”

“Sonic was its own story with lots of issues, many of which are well documented,” Lander said, “and certainly the harsh reviews didn’t help but there were more forces at work.

“Realize no one starts out saying I want to make a lower-than-50 rated game,” Lander said. “Even on a low budget you want to do good and spend years on it. But stuff happens and sometimes it doesn’t go well. The hardest is when you know it is actually pretty good but for whatever market reason reviews are not good and people pile on. Then it really hurts. But the team usually develops a squad mentality that as long as the culture is still good people will probably stick it out. Particularly vets. Everyone has had bad games. Some worry about reputation and may move on.”

Credit: Sega

Like other pretenders to the throne, Haze was deemed a “Halo Killer.” But creative director Derek Littlewood, who’s now the studio design director at Sumo Digital, didn’t agree with that moniker and said it was uninvited. “I think the idea of two competing developers, making FPS games for rival consoles, was an exciting narrative for some, but it wasn’t a thing that had any basis in fact,” Littlewood told Engadget back in 2014. According to that report, a new engine and pushes from Ubisoft to add more content created a troubled development cycle, and the hype surrounding it created a wave of backlash when the team didn’t deliver.

“It sure isn’t fun reading a negative review of something you’ve put years of your life into,” Littlewood told EGM, “particularly when the development process hasn’t been entirely smooth (which, well, there’s at least some correlation between difficult dev cycles and less than stellar reviews).”

But instead of letting the negative reviews beat him down, Littlewood took them as a learning experience.

“I thought the vast majority of reviews I read for Haze were pretty fair,” he said. “The thing that hit me the most wasn’t the critique but rather the overwhelming sense of disappointment. For people to value your company highly enough to be disappointed, that’s a pretty privileged position, and seeing people hope for something great and then feel let down—that hurt probably more than anything else. But I don’t think they were wrong to be disappointed. The game just wasn’t what it should have been.”

Credit: Ubisoft

One strategy is to not read reviews at all. When Yaiba: Ninja Gaiden Z came out, reviews criticised everything, especially its attempt at humor. Eurogamer thought that “some of the jokes might raise a smile if you’ve recently suffered a head injury,” and Jim Sterling, writing for The Escapist, said that it “manages to be one of the worst games of the last generation, right at the very end of it.” But lead designer Cory Davis didn’t let them get to him.

“I don’t read or think too much about the reviews of my projects,” he said. “It would poison the well from which they emerged. I’m trying to break the status quo, and I don’t expect reviewers to always get it when the project is released.”

What really matters to Davis when it comes to feedback on his projects are the communities surrounding those games. “It can take years for the community to come to a consensus on the quality of a project. I pay very close attention to what they say over the years.”

Credit: Koei Tecmo Games Co., Ltd.

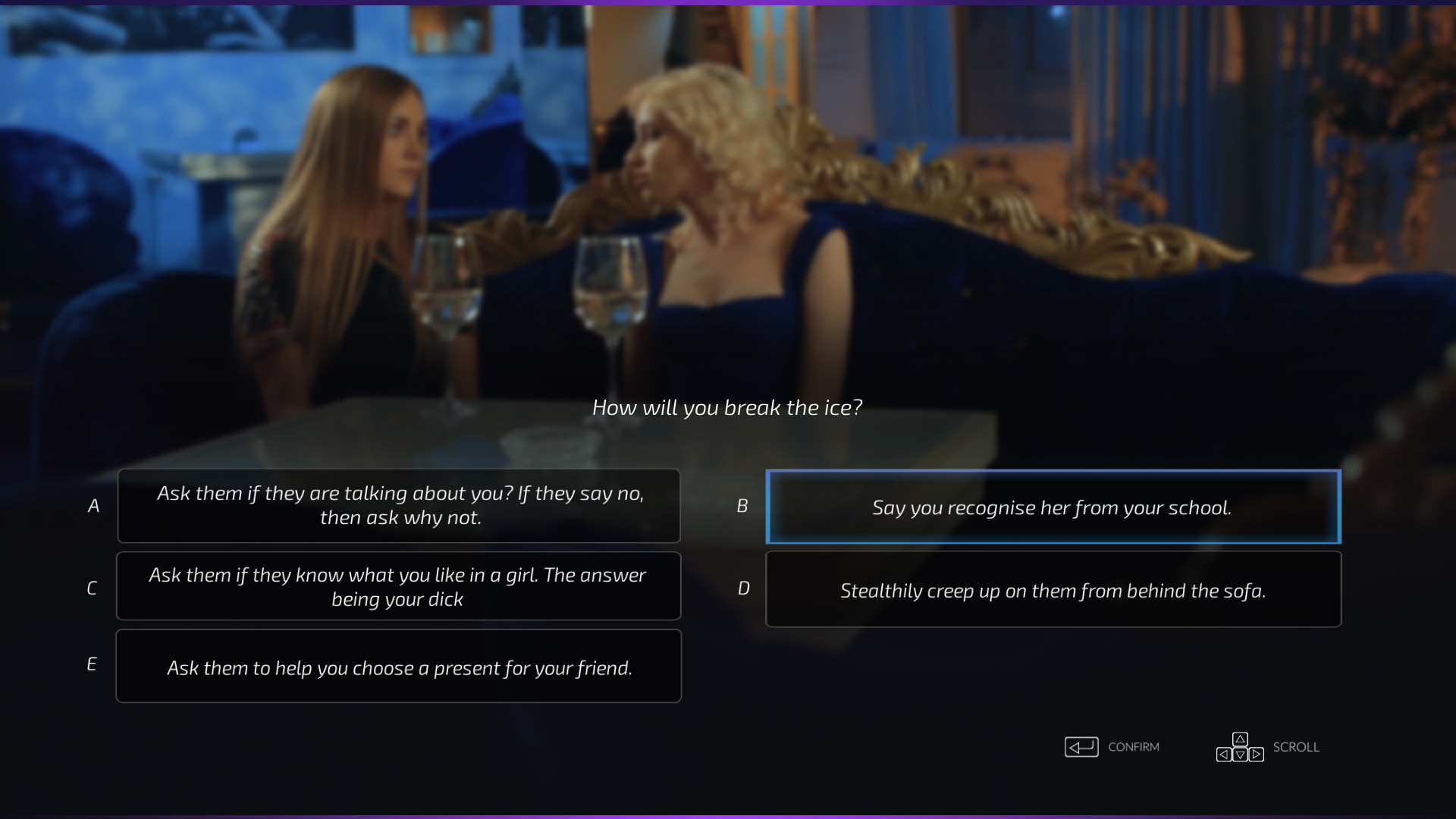

In the case of Richard La Ruina, however, reviews for the first Super Seducer were an extremely personal affair. Kotaku called it a “Dragon’s Lair for assholes” and Level Up co-founder Carys Afoko said that it was “training for the next generation of Harvey Weinsteins” in a Guardian article the media outlet has since taken off its website after agreeing to an out-of-court settlement that awarded La Ruina £12,000.

“Anyone can say, I don’t like Richard, he’s creepy, that’s not defamation, but if you say, this game teaches men how to rape women, that’s proven subjectively false and we can prove that in court,” La Ruina said.

All the negative reviews and attention surrounding Super Seducer “actually made me hate critics,” he said. “It’s someone who couldn’t do what you’ve done but can’t give you any credit for it.” La Ruina saw the negative reviews as “very personal. They picked on individual things in the game. They’d even insult stuff like the music. Couldn’t you just say you liked the music? Wouldn’t your review be more balanced. You could say I hate Richard, I hate the game, but the music was pretty good or it was well-shot. Give it something to kind of balance out the negative.

Credit: RLR Training Inc. and Red Dahlia Interactive

“We had such a small team, so it’s a specific person if you’re talking about each individual complaint about it,” he continued. “You’re kind of attacking a specific individual and the reviews were quite personal, which is not something you’d ever see with a title from a big publisher that had thousands of people working on it.

In La Ruina’s mind, the reason why press surrounding Super Seducer was so negative is simple: “They want to write a story that is like: this is the most horrible game ever. They want those clicks because it’s good clickbait. And they’re ready to throw anyone under the bus, and they’re ready to misstate facts.”

Better red than dead

The voice of the masses has power. We see how word of mouth and buzz on the internet can affect things like a movie’s opening weekend or reactions to a YouTube video. It is often believed that this applies just as strongly to games as well. When the scores are bad and the critics all pan a title, it’s easy to believe that the game has tanked. With such forces against it, how could anything succeed?

However, other factors beyond reviews seem to have a larger effect on whether or not a game has market potential.

“I think it depends on the game,” Littlewood said. “Games with franchise or brand recognition will be less affected by review scores, for instance, whereas for a small indie title, a round of great reviews can be a huge boost (and the inverse for bad reviews). But that said, the picture is clearly much more complex—we all know of games with so-so reviews that have sold vastly well, just as we all have a special game we remember that was critically acclaimed then sold about ten copies.”

Credit: Ubisoft

More than directly impacting sales, negative reviews can cause publishers to reel in the marketing plans on a new release. According to Lander, “bad reviews can sour relationships with publishers such that they don’t put marketing behind it.”

“I can say I have had many conversations with friends in the industry where the publisher was very supportive and excited about marketing a game and working with the team,” he added. “But then with negative reviews that kind of publisher support dried up and conversations about sequels and expansions ended. You see that sometimes make its way in the news where a publisher announces a sequel but then the support is pulled based on market perception.”

Ironically, negative reviews can sometimes help sell a game. “Negative reviews can actually have a positive effect if the developers can show they are trying to fix the problems,” said Lefor. Trials of Ascension, for example, is still in early access, and if potential players see that a developer has put work into a game and is listening to its fans, they might be more willing to give the game a shot.

Credit: Ripened Peach Games

Jenna Fearon, whose studio Ripened Peach makes “sexy games for adults,” said that a negative review of the game actually helped it sell more copies because, in some instances, any press is good press.

“People rarely review our games,” Fearon said. “There was one review ages ago on Rock Paper Shotgun [for the game Sex Sim], and although it was pretty down on the game (because yuck, sex!), it got us a ton of traffic and sales.”

In the end, there’s one number that matters more than a review score, and that’s the almighty dollar. Especially when it comes to getting a sequel, public opinion is a minor part of the equation.

“I’d guess reviews are a small part of the picture,” Littlewood said, “but if a game reviews poorly but still goes on to sell well, I’m certain that game has a much better chance of getting a sequel than the converse.”

Unfortunately, the inverse can also be true. Even if a game is a critical darling, if it doesn’t put up the numbers, that could spell the end of an entire series.

“I have a good friend who was recently on a [triple-A] game sequel to a game that was a critical hit and reviewed really well,” Lander said. “The sequel had equal buzz and strong reviews but for whatever reason didn’t sell and the publisher dropped the franchise. So reviews are clearly not the most important thing.”

Moving on from negative reviews

For most developers, negative reviews aren’t the end of the world. In some cases, they can actually help developers, albeit circuitously.

“A bad review with good constructive criticism can be more helpful than a good review that is just telling you how awesome everything is,” Lefor said.

What’s more important to studios looking to hire developers isn’t necessarily that a game reviewed well, but that it was finished at all.

“As an employer,” said Lander, “I may ask why does a candidate think a game turned out bad. But I always say, ‘Did it ship? If so, congrats.’ That is hard enough. Sometimes you don’t get publisher support, or the leads are fighting with each other or pub or scope or console targets change, whatever.”

Credit: RLR Training Inc. and Red Dahlia Interactive

Not everyone lets go of the negative reviews, however, least of all Richard La Ruina. After the criticisms of the first Super Seducer, La Ruina said that for the sequel his team tried to “pander a little bit so we added in the female perspective levels and Charlotte as my co-host leaving feedback, we were a lot more careful, and now the user reviews for SS2 are actually a little bit worse than SS1. Some people are saying it’s the SJW version of Super Seducer.” However, despite what La Ruina claims, user reviews for the game on Steam are currently very positive.

“I lost a lot of respect for critics,” La Ruina said. “Now I look at the user reviews, where before I might have trusted the IGN or whatever review. I’d be totally fine not receiving another critic review for whatever we make.”

In the end, the kind of negative attention that Super Seducer attracted can take a toll, especially on people who aren’t used to or ready for it. La Ruina saw this happen to people who worked on his game, specifically the women who featured in it.

“If someone is not used to being a public figure,” La Ruina said, “I think it can lead to loss of sleep and depression, all kinds of problems, to have your name dragged through the mud or to have people on Twitter saying they hope you die. That’s hard for people who aren’t used to being celebrities or used to the public eye.”

Header Image Credit: Koei Tecmo Games Co., Ltd.

Writing from a basement in Silent Hill, Wilds is one who draws his inspiration for writing on things like having never beaten Battletoads, errant commas, and old cartoons that only received one season. He has penned words for sites like Playboy, Polygon, Unwinnable / Exploits, and Paste. He’s best found on Twitter @StephenWilds.