One day in grade six, I spotted a copy of The Blair Witch Project on Eric’s desk. I remember glaring at it through a math lesson. A sterile plastic cassette that was still conjuring a national panic. While the studios weren’t hiding its fictional status, people still weren’t convinced that the Black Hills of Maryland were safe. The Blair Witch, never shown and known only through the dread she instilled, made the cassette feel like a cursed object. The less we saw, the more we became intimidated by our own conclusions. There’s more to fear in the dark.

Now, in 2019, the Blair Witch has returned—just not on videotape. Bloober Team, the developer behind Layers of Fear and Observer, is releasing The Blair Witch Project on August 30th for Xbox One and PC, taking inspiration from the original film’s found-footage style for its own torrid walk through the woods. The studio’s knack for misdirection feels like a good fit. Even the developers of the original Blair Witch games seemed excited to see their take on the material.

After all, this isn’t the first time the infamous film has been adapted into a video game. Gathering of Developers—the original publisher of Max Payne, Tropico, Serious Sam, and Mafia—launched three Blair Witch Project tie-in games in the span of two months, each made by a different studio.

The speed at which these games—Rustin Parr, The Legend of Coffin Rock and The Elly Kedward Tale—came together is spooky, even by the standards of PC gaming’s ’90s heyday. The Blair Witch Project first hit theaters in July of 1999. All three games were in players’ hands by November of the following year. EGM spoke with the developers and publisher behind these largely forgotten titles to find out how an existential horror film became three gun-slinging action games.

The original Blair Witch Project was a micro-budget sensation. An unusual production, great care was taken to selling the illusion that its three documentarians had vanished in the Black Hills through online supplements, TV specials, and the decision to cast of amateur actors. There’s as much lore about the film’s Sundance debut as there is about the Blair Witch herself, that even producers and distributors were duped and demanded answers about the footage. Joe Jing, designer of the first Blair Witch game, told me that one of his advertising buddies was fooled by the film’s promotion. The scary little tape became a phenomenon—and nothing undoes a phenomenon quite like itself.

Movie studios weren’t going to lay a horror hit to rest during the Scream era. Blair Witch got a hasty sequel without the involvement of creators Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez. Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, no longer presented as found footage, followed a group of youths obsessed with the original film dooming themselves by camping in the suddenly elaborate house of Rustin Parr, the Blair Witch–driven killer central to the first film. It’s early-aughts trash horror to a fault, with stock characters—prep, goth, stoner—and a soundtrack that featured Marilyn Manson, Elastica, and Nickelback.

Everything that Blair Witch set out to do differently was swiftly ruined by studio mechanizations that demand sameness. But the video game adaptations, oddly enough, might not have happened without Book of Shadows.

The deal to make a trilogy of games was cut at E3 1999 by Gathering of Developers founder Mike Wilson, now one of the founders at Devolver Digital. In an email, Wilson said that the rights to The Blair Witch were quickly passing from the small original Floridian producers Haxan to Artisan Entertainment. Even though they couldn’t get Myrick and Sánchez on board, Artisan was dogmatic about getting more Blair Witch for Halloween. Book of Shadows would eventually make that cutoff, releasing on October 27th, 2000. Gathering of Developers, for its part, wanted games out alongside the sequel.

Those who worked on the games don’t recall many stipulations from the studios and had no interactions with the filmmakers. To avoid creating paradoxes, the three dev teams decided to make prequels set in different centuries.

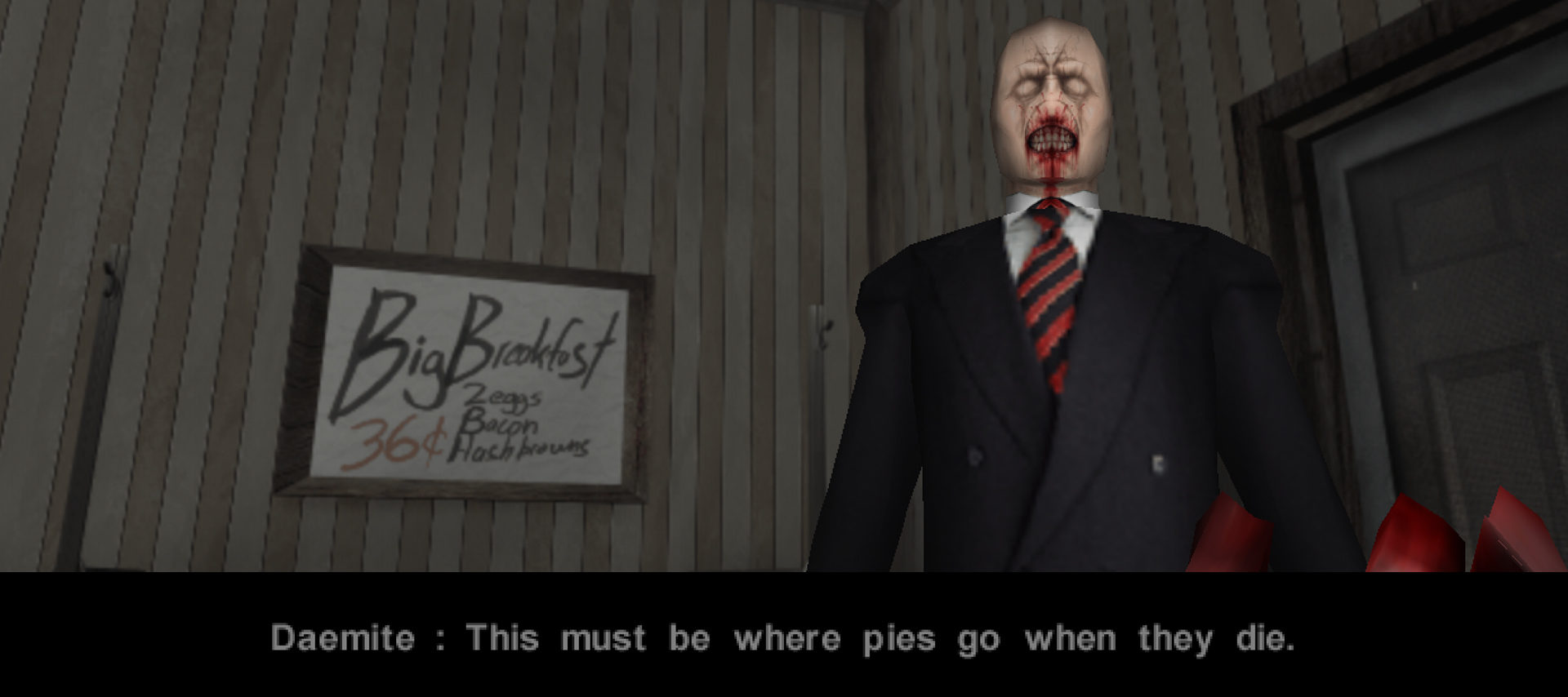

In stark contrast to the original film, you do see monsters in Terminal Reality’s The Blair Witch Vol I: Rustin Parr. You see plenty in the first 10 minutes. You’re attacked by skinless zombies. Then three were-bats lunge at you. Some reptilian ghouls pop out here and there.

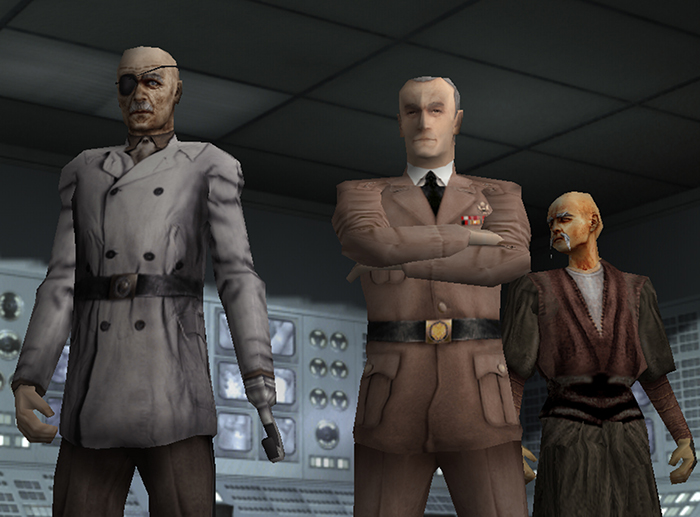

The game’s British, beret-wearing protagonist, Elspeth, seems unperturbed about the horrible beasts storming around. So do her companions, a one-eyed army officer, a leather mama, and a martial arts guy dressed uncannily like Ken Watanabe in Batman Begins. They’re casually fearless, a stark contrast to the film’s cast infamously glazed in dirt, tears, and mucus pleading for help through cold, shredded whimpers.

This is because these characters are on loan from Terminal Reality’s previous horror game, Nocturne. Nocturne followed Depression era paranormal investigators hunting down vampires and Frankenstein mobsters as part of a covert organization founded by Theodore Rosevelt. The star of that adventure is named The Stranger, who comes barreling in with dual pistols during the Blair Witch game’s tutorial. This team, you soon learn, is tasked with investigating the Rustin Parr murders.

Joe Jing, Rustin Parr’s designer, regrets that the crossover connection wasn’t made more explicit, but said that building the game out of Nocturne was the only way to make the tight deadline. “I think the development and outcome was less than ideal for almost everyone,” Jing said. “Blair Witch movie fans weren’t necessarily gamers and gamers weren’t necessarily clamoring for a game set in that world. Even Nocturne fans weren’t thrilled the game wasn’t a true sequel.”

While only one Blair Witch game used Nocturne’s characters, all three games used Terminal Reality’s proprietary engine. Rune creators Human Head Studios and SiN makers Ritual Entertainment had no experience making horror games. Jing recalls crash courses with reps from the other studios on how to use the, in Jing’s words, “not user friendly” engine. Jing also said that, despite the film’s cast standing zero chance against the otherworldly, Gathering of Developers wanted a heavy action slant. The main characters of all three games, in all three eras, wear wind flapping dusters and pack heat.

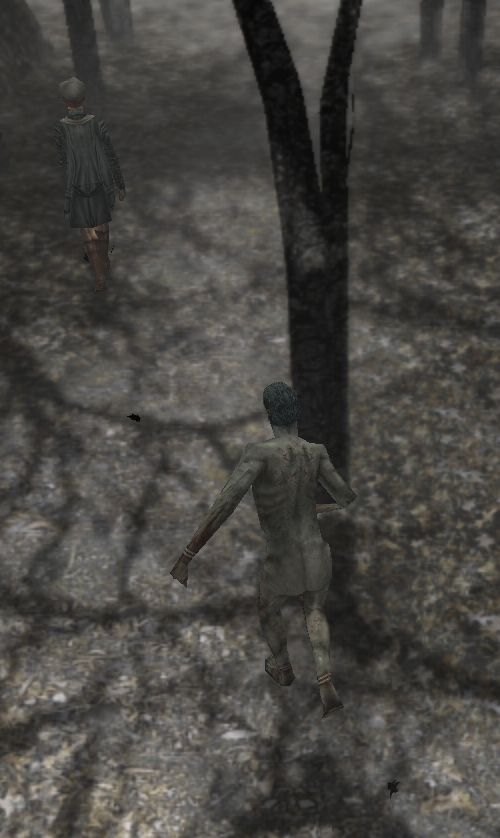

Human Head’s The Legend of Coffin Rock concerns an injured Union soldier coming to in the woods, joining a search party to find the now-missing girl who discovered him bleeding by a tree. The Elly Kedward Tale, from Ritual, stars a witch hunter tracking Kedward, a banished wyrd woman. This third part serves as a loose origin story, assuming the Blair Witch came to be in a place resembling a Quake map.

Jonathan Galloway, art director and designer on Elly Kedward, said he wasn’t scared by the film, but discussions about the movie in following weeks served as inspiration. “We basically had a few tentpole details to weave around,” Galloway said. “The name Elly Kedward, a time period and a location. We drew what we could from the first film, other games, and any additional mythos and theories we could dig up.”

Even if there aren’t explicit canonical mistakes with respect to the source material, the three games are tonally inconsistent. Pumping a semi-mechanical, semi-zombified golem shaped like the famed twig figure full of lead just doesn’t feel very Blair Witch-y.

Book of Shadows couldn’t escape its natural trappings as a year-2000 horror sequel, and the PC action tie-ins couldn’t escape their inherent impulses either. All three begin with interrogating or irritating the locals, but once the dead rise from their graves, guns are permanently out from their holsters.

In her first night in Maryland, Elspeth suffers a vivid nightmare where all the kind townsfolk are demonified. Even in her worst dreams she’s still Neo, and very few of the vicious creatures make it more than a few steps. Throughout Coffin Rock, Lazarus, the Union soldier, has flashbacks to the Civil War. You dispose of Confederate soldiers in the past and then blast away their ghosts in the present—a unique kind of overkill. Elly Kedward takes you to “the demon realm,” where you fight no less than the lords of Hell itself.

Two decades later, the developers of the original game trilogy know the circumstances and limitations to what they made. They know why they’re not classics. Jing told me in his first email that he didn’t think anyone remembered his game, and still seemed stunned that the studios managed to pull off the trilogy at all. Galloway cited crunch as a key factor.

Wilson, for his part, spots a direct lineage between his work on the Blair Witch games at Gathering of Developers and his accomplishments since then. Blair Witch, he said, “further cemented” the philosophies he employs at Devolver, comparing the underdog success of Myrick and Sánchez to Nuclear Throne’s Vlambeer and Hotline Miami’s Dennaton.

“They were cool dudes from Florida who had suddenly been cast into the spotlight,” Wilson said of the original film’s creators, “[an] example for what was still possible with a small team and no budget.” He wants to see more games made like The Blair Witch Project and fewer like Book of Shadows.

Looking at the current media landscape, it’s hard to argue. There haven’t been many Blair Witch Projects since The Blair Witch Project. And it’s not because people stayed out of the woods.

Header image: Blair Witch Volume II: The Legend of Coffin Rock

Zack Kotzer is a former carny and current writer out of Toronto. His work has been published in The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, Motherboard, Polygon, Kill Screen, and a column in NOW Magazine. His first book, Keeping the Ball Alive, details the history of the only pinball factory to survive the ’90s. He collects Fido Dido merch.