To tell the story of A Life Well Wasted, you have to start at the end: Armageddon.

Well, the Armageddon of gaming magazines at least, including the initial closure of Electronic Gaming Monthly in 2009. At the time, Robert Ashley was a freelancer for magazines like EGM and, alongside musician Sam Frigard, one half of the psychedelic-pop duo I Come to Shanghai.

He quickly realized that he couldn’t handle the grind of writing for websites and really needed a new job. He didn’t have formal radio training, but he had gathered equipment and skills from recording and mixing music.

“So I had this idea: What if I made a radio show about video games? What if I made all the music for it myself? What if I did it in a fast-cut style with hundreds of tiny edits? I bet I could put out one of those every month.”

That’s Ashley, from the introduction to “Big Ideas,” episode six of A Life Well Wasted. Like the NPR shows that inspired it, the show is immersive and largely focused on regular people with fascinating stories to tell. Episodes often devote as much time to, say, interviewing a collector, the founder of a gaming-themed art gallery, or the hosts of a fan-fiction radio show as they do profiling prominent industry figures. Bolstering this is a distinctive blend of longform interviews and music, the latter provided by I Come To Shanghai.

“Even when I worked for magazines… I always felt like an outsider,” Ashley told me. “I would go to a conference like GDC or E3 and I’d spend the whole time feeling like I didn’t belong or something, and so there are these marginal people in the business who I’ve always been attracted to. Having stories about them makes me feel like more of a part of it, I guess.”

Courtesy Robert Ashley

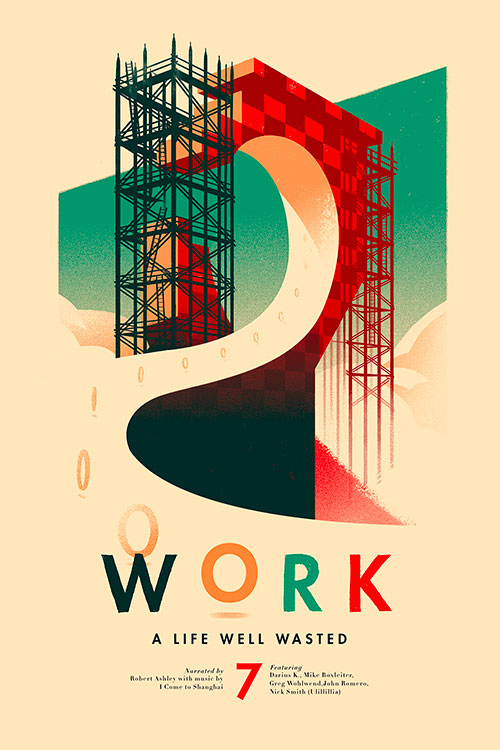

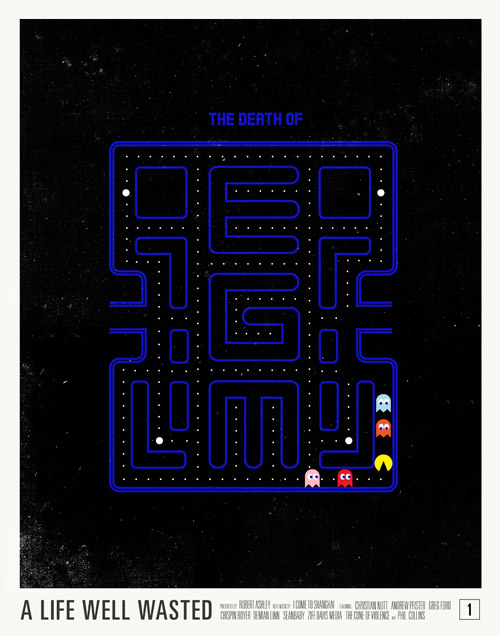

Each episode has a theme, like “Why Game?” or “Gotta Catch ’em All,” with the inaugural episode focusing specifically on Electronic Gaming Monthly. Posters designed by a fan of the podcast, Olly Moss—now well-known for his work with the design firm Mondo and on the Campo Santo game Firewatch—offered a revenue stream for Ashley.

After six episodes between 2009 and 2010, the show went on hiatus until 2013, when it returned with the episode “Work.” The episode, which included an interview with id Software co-founder John Romero and a profile of eccentric internet personality Nick “Ulillillia” Smith, didn’t sell itself as any kind of coda for the show. In fact, Ashley even solicited tips for future stories at the end. But since then, radio silence.

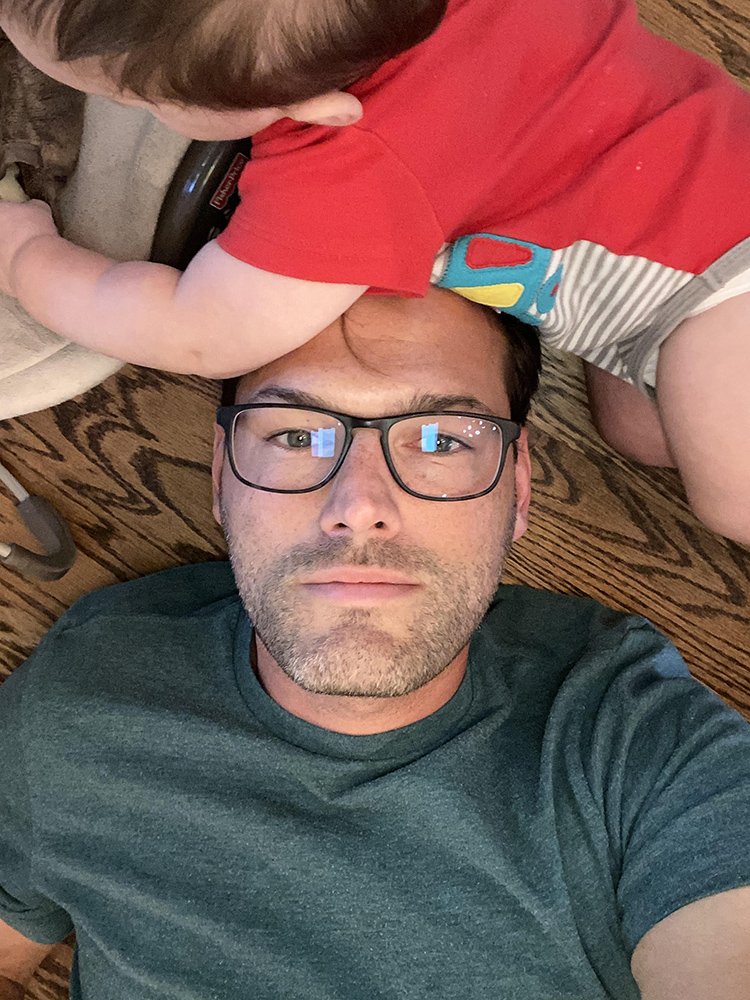

Ashley now lives with his family in Norman, Oklahoma, and he’s not done with A Life Well Wasted just yet. Work on the next episode is already underway, with the potential for more to follow after that.

“I would think that if I cannot get [the next episode] done this year that I’m just gonna have to drown myself in the creek,” he laughed.

Ashley, originally from Texas, developed a love for gaming magazines around middle school.

“When I was a kid I didn’t get to buy games, kind of like ever… but my mom would always buy me gaming magazines. I was really obsessed with that stuff, specifically EGM.”

Ashley got his break while studying at the University of Texas as an English major, writing video game reviews for the student newspaper. After college, he moved to Washington, D.C., with his wife and started working at Wolf Camera. But he was “desperate to figure out how to make something happen professionally” and started sending out writing samples, eventually landing freelance work with EGM. After his wife got into grad school at UC Berkeley, the couple moved to California and Ashley started a “full-time freelance writing gig” at EGM, making music in his spare time.

Eventually, Ashley got burnt out reviewing games and transitioned into feature writing, which helped lay the foundations for A Life Well Wasted, as did his regular stints on the influential GFW Radio podcast, which ran between 2006 and 2008. Around this time, Ashley found himself growing increasingly frustrated with the limitations of magazine journalism.

“[Magazines like EGM] did, toward the end, allow me to do more people focused stories, but I got very frustrated with getting on a plane and flying 12 hours to someone’s game studio and meeting all kinds of interesting people but then coming away with it, writing a story about ‘What are the 10 guns that they’re gonna let you shoot in this game,’ just really fucking lame ideas of what kinds of stories you could write about a game.”

Courtesy Robert Ashley

When he first decided to start the podcast, Ashley was “really nervous.” He had managed to make a living for years by freelancing, turning down full time jobs in the process, but the closure of magazines like EGM around 2009 forced him to adapt. “Luckily, my wife had a pretty generous stipend in grad school, and we had saved enough to give me space to experiment,” he said.

Ashley’s experiments have proven fairly popular. Episodes of the podcast have been downloaded over 951,000 times, according to Libsyn statistics shared with EGM. Surprisingly, 52,000 of those downloads have come since 2017. Despite the long gap between releases, new listeners are still discovering A Life Well Wasted, with Ashley estimating that episodes get “a couple hundred downloads a month” these days.

In addition to the posters Moss designed, which Ashley used to package and mail himself with help of a fan, the podcast has also sold t-shirts as a means to generate revenue. “After paying Olly way less than his popularity demanded and paying for all the printing and shipping… I could net somewhere between $4k and $8k [per episode],” Ashley said. “It wasn’t exactly a lucrative gig, but it felt okay at the time.”

Ashley conducted many of the interviews for the podcast in person, occasionally traveling by plane just to secure a good story. For example, his interview with hardware engineer and Tilt Five CEO Jeri Ellsworth was conducted after he saw her give a talk at a Maker Faire in Northern California. They sat in his jeep, both facing forward, and had an “incredibly personal conversation.”

“I feel like it would’ve never been that way had we not been sitting in the car,” Ashley said. “The quiet space and a place where so many people end up having these kinds of conversations… The thing that I crave most is for someone to just be really themselves.”

This closeness, however, can have drawbacks. Ashley recounted a time he was followed to a concert by an interviewee who wanted to keep talking about their life.

“[People] don’t have someone who is willing to sit and listen for as long as they want to talk about whatever,” he said. “A lot of people need that.”

He also ran into trouble when the office of the Tetris Company’s Henk Rogers complained that Rogers’ profile was included in an episode that also featured Jonah Falcon, a blogger and actor who claims to have one of the world’s largest penises.

“This is why I don’t interview people who are, y’know, big in the business because they have a lot of PR levels and shit that I just refuse to navigate,” Ashley said.

Ashley expressed regrets for his portrayal of Falcon, who experienced some online abuse after his appearance on the podcast.

“I know now that you sometimes have to challenge someone if you’re gonna use something that’s gonna make them look in a way that they don’t wanna look,” Ashley said. “I really just want people who come on the show to hear themselves when they hear it… I don’t want them to feel regret about it.”

Courtesy Robert Ashley

While uninterrupted monologues carry the main storytelling segments, the podcast is defined by music and clever, dense editing. In one episode, a cosplayer listing off her costumes is cut into an impromptu rap song. In episode six, Ashley took contributions from listeners pitching their dream video game and turned them into a five-minute musical odyssey.

“Each [episode] took more time than the last one, because I was always turning up my expectations of what it was I wanted to do,” said Ashley, who spent “a couple of hundred hours” on some later episodes.

“[When] I got into the obsessive zone, I would work on it all day and half the night, just going kinda crazy on it… I didn’t want to move.”

Ashley is keen to emphasize that he never worked entirely alone—his wife was “indispensable” in the editing process, filtering out uninteresting moments for non-gamers, and his bandmate Frigard helped with music. After the first six episodes, Ashley moved to Athens, Georgia, to work on music full time. After releasing episode seven in 2013, Ashley and his wife had their first child while I Come to Shanghai focused on recording the album Low Pressure. Released in 2017, the album was the culmination of years of work that Ashley described as “maybe the most creative hell I’ve ever been through.”

“[Sam and I] went totally nuts and lost our minds, and I think that’s probably at the heart of all of my creative problems and self-doubt, just really going down the rabbit hole of that whole thing and in the process just getting so far away from podcasts,” he said.

Ashley has been a stay-at-home dad with his children in recent years. He described experiencing “a crisis of self-confidence with everything that I do.” Podcasting had taken off in a major way, and human-interest game journalism was on the rise as well.

“I had such a hard time with it for a while where I just looked back at the things I made, both podcasts and music, and I had a really negative attitude about it,” Ashley said. “Lately, I guess I’ve been able to look back and feel good about things again.”

However, Ashley occasionally has a hard time connecting with modern gaming culture as it’s transitioned from being considered marginal and nerdy—“Only weirdos were into it”—to a mainstream pastime with a minority of “obnoxious trolls who act like horrible people to women online and various other people.”

“I started out celebrating the culture of games because I had met so many really cool and interesting people who were involved,” he said, “but it’s that ‘online effect’ when you get exposed to the negative side of a culture.”

“I’m not gonna have stories about the parts of the culture that I find gross. I’m gonna go out and find people who are the opposite of that.”

Following its upcoming return, Ashley anticipates he’ll continue to produce A Life Well Wasted on some level in the future, viewing it as an art project rather than a consistent, commercialized product. He said he’s accepted his fate as “a middle-aged dad musician whose band didn’t make it.”

I asked if he’d considered abandoning the podcast at any point since the last episode released, now more than seven years ago. “A smarter person would have probably moved on by now,” Ashley replied, “but I’m the kind of person who can’t give up on something once I’ve started it. I have to finish it.”

And if podcasting doesn’t work out?

“I think I can always be a greeter at Walmart. That’s the economic future that I always see as a possibility,” he laughed.

Header image derived from poster for A Life Well Wasted Episode Six: “Big Ideas,” courtesy Robert Ashley.

Niall is a freelancer from Ireland; he accidentally fell into Lordran one time and he’s still looking for a way out. Previous bylines with outlets like The Irish Times and Rock Paper Shotgun.