“Why am I in an industry where my mere presence means I’m going to get death threats?”

It’s a question Meghna Jayanth, writer of 80 Days and the upcoming Sable, often asks herself. As a high-profile Indian woman who has spoken out on representation, sexual harassment, and creeping white supremacy, her very existence offends some people. But to others she’s proof that they, too, can make it in the industry.

Five years ago, Jayanth, now 33, was reluctant to see herself as a role model, but after the best part of a decade in games she’s more comfortable with the label. “People have come up to me and said that [they feel] there’s a space for them here, that the issues that matter to them are being talked about,” she says. “I really want more brown and black faces in the industry… If my visible presence in the industry makes other people feel like they belong here, that’s a good day at work for me.”

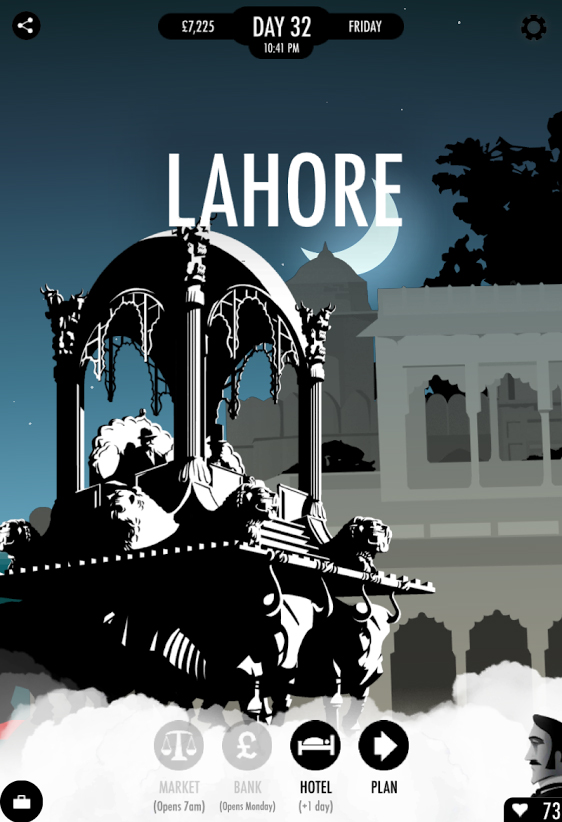

Naturally, it’s not just developers from marginalized groups that look up to Jayanth, who also has writing credits on Horizon: Zero Dawn, Sunless Sea, and Falcon Age. Her work with British studio inkle, developer of 80 Days, established her as one of the most talented narrative designers in the industry. Jayanth wrote most of the game’s 750,000-word script, for which she won a U.K. Writers’ Guild Award, while curled on a sofa in her cozy flat in Bow, East London—the same sofa I sit on as we speak. A pajama-clad Jayanth would stay up until 2 a.m. to get her thoughts on the page, filing copy to inkle co-founder Jon Ingold, with whom she jointly wrote the game. “It’s steeped in so many all-nighters, and so much stress.”

She’s lived here 10 years, but now she’s leaving that sofa, and that stress, behind. Her and her partner, Robert Morgan, creative director at augmented reality studio Playlines and Jayanth’s perennial first reader, are packing their belongings into boxes when I arrive. “Sorry about the mess,” Jayanth says. But for a couple about to uproot and move to Brighton—via Bangalore, India, where they’re staying with Jayanth’s parents for a few months—their apartment is remarkably ordered. The only hint of chaos is the stacks of scrubs and lotions in the bathroom, and the dregs in the soap dispenser. “Anything that’s on its last legs is getting used up.”

Their move starts a new chapter in Jayanth’s winding story. 2020 will be a year of transition: It will mark the release of Sable, from debut studio Shedworks, and the full launch of Red Queens, a partnership between Jayanth and writer Leigh Alexander, a long-term friend. As she did with 80 Days, Jayanth has plenty of freedom to write what she wants with Sable, which follows a young woman finding her place in the world. But Jayanth wants more. She wants to make her own games, rather than freelancing for different studios. Red Queens, the culmination of everything she’s learned in the industry so far, is her chance to do just that.

Even as she recounts a 2018 health crisis that forced her to take six weeks off, or the abuse she faced after hosting the 2019 Independent Games Festival Awards (“only a week or two of harassment,” she says), she laughs well, and often. Between numerous cups of coffee—half regular, half decaf—she slips out to her small balcony for cigarettes but carries on answering questions through the open glass door, blowing her smoke sideways into the cold London air while smiling and joking. She seems like a woman who’s more optimistic about her work, and perhaps her life, than she’s ever been. And with good reason.

It’s impossible to separate Jayanth’s writing from her upbringing. Just as Passepartout roamed the world in 80 Days, she spent her childhood traveling, and grew up between the U.K., Bangalore, and Saudi Arabia. Once, she and her family spent a night with a group of Bedouin monks: Her parents are both doctors and a patient had invited them into the desert as a thank you. “There was a monitor lizard tied outside the tent,” she recalls. “My dad, who’s a vegetarian, said, ‘Oh, what an interesting pet’—only to discover that, of course, they’d spent three days preparing this lizard, and it was a delicacy that was going to be cooked for the feast that night.”

Jayanth’s father inhabits her earliest gaming memories. Whenever she reached the magic carpet lava level in Disney’s Aladdin on the SNES, she’d put the controller in his steady surgeon’s hands. “The sizzling sound is still in my dreams,” she says. “I hate ‘A Whole New World’ to this day. Rob says it’s one of the most romantic Disney songs. He’s wrong.”

For the young Jayanth, playing games was always cooperative, never exclusionary. As the only kid with a console among her friends in Bangalore (she’d bought it in the U.K.), everyone would gather at her house for bouts of Street Fighter. “I was never particularly good or competitive, but it never felt like a big deal.”

She played SimTower, Civilization II, plenty of interactive fiction and—not with her father, this time—the original Grand Theft Auto on an old DOS PC that needed 12 floppy disks to boot up. “I don’t think I did any of the main missions in GTA. I was just going around stealing things, mowing down Hare Krishnas. That was a big part of it,” she jokes. “I personally don’t like Hare Krishnas. We don’t have to get into that. Better if we don’t. They try to sell me Bhagavad Gitas on Oxford Street, and I feel a little bit annoyed by that, because they’re white people in dreadlocks trying to sell me my own culture for a markup.”

Games were seminal for Jayanth, but she was never into gaming culture. Because she traveled a lot, games were sometimes a solitary joy: She didn’t have the best time in school, she says, and her console was often her escape route. But she didn’t read gaming magazines, or keep up with gaming news and trends. She skipped a few console generations, and it wasn’t until university back in the U.K., where she studied English Literature at the University of Oxford, that she first played on an Xbox 360. She spent an entire holiday with GTA IV, and it was a struggle. She wasn’t used to controlling a camera with an analog stick.

“Even though I loved games and I’d played a lot as a kid, having these new controllers… it was a complete learning curve.” She’d heard friends rave about Halo, and tried it, wanting to learn and love it. After much frustration, it clicked. But she recognized that if she hadn’t known the joy waiting on the other side of mastery, she would’ve given up.

It’s part of the reason she loves mobile gaming. Anyone can play on a touchscreen, which opens games up to a whole new audience. It’s allowed her parents to keep up with her work, too. She showed them all her writing early in her career (including her Harry Potter fan fiction). They played and loved 80 Days, but they got distracted by buying and selling items to make money between ports and forgot about the whole Around the World bit, she says.

While studying at Oxford, Jayanth directed the prestigious Oxford Revue comedy group, whose former members include Rowan Atkinson, Maggie Smith, Michael Palin, and the late Terry Jones. She describes the job as halfway between a nursemaid and a traffic warden: She herded smart, young Oxford men (Jayanth was one of three girls in the 20-strong group) around the Edinburgh Fringe, where the group went down a storm. “They were constantly bringing women home… You’d wake up and wander into the living room and there would just be naked people.”

As well as directing the group, Jayanth took charge of the cleaning schedule, and taught vital life lessons, such as how to chop an onion. “A member of the Revue, whose name I won’t mention but is currently a Guardian columnist, said to me the words: ‘Aren’t toilets self-cleaning?’ At which point I said: ‘No, darling, your mum does that.’”

It was at the Fringe that Jayanth met one of her idols, British stand-up comedian, writer and director Stewart Lee, another former member of the Revue. She queued up for an autograph, and when she reached the front, Lee asked: “Aren’t you too young to know about Fist of Fun [Lee’s BBC Radio 1 series]?”

“I said the only three words I’ve ever said to Stewart Lee. ‘Yes,’ ‘No,’ and then, ‘Maybe.’ And then I left, and I never saw him again. There’s no recovering from that.”

At Oxford, Jayanth met her partner, Morgan, while directing a Terry Pratchett play. Morgan, an ex-boyfriend of Jayanth’s best friend, auditioned for the part of the Evil Hunchback Duke. “I really didn’t want to cast him. I’d texted my friend, ‘Your shit ex-boyfriend has shown up.’” Morgan, however, was “annoyingly good”: during an Out-Damned-Spot-style monologue, he cheese-grated his hands in a way that made a horrifying noise without dealing any lasting damage. Her friend was fine with the casting and, later, on-board with the couple’s relationship. So was Jayanth’s mother, who wanted to know what type of conditioner Morgan used. “He had really long, ridiculous hair at that point. He’d wash it in beer and stick pens in it.”

After leaving university, Jayanth hopped between design roles before landing at the BBC in London, primarily working in the broadcaster’s games commissioning arm. She was laid off when the entire team relocated to Salford, near Manchester, in 2012, and with time on her hands, she moved back in with her parents to begin work on Samsara, a piece of interactive fiction set in 18th century Bengal.

It remains her biggest ever project, and she still hasn’t finished it. She submitted a chunk to Failbetter Games’ StoryNexus competition knowing that, at the very least, it’d get her writing in front of judges Susan Arendt, at the time executive editor of The Escapist, and Mike Laidlaw, then creative director of the Dragon Age series (Laidlaw praised Jayanth’s “evocative, lavish writing”). Samsara won and, perhaps more importantly, caught the attention of the developers at inkle, who asked Jayanth to write for an upcoming mobile game based on Jules Verne’s classic novel, Around the World in 80 Days.

If Jayanth had known the scope of what she was getting into, she would’ve been overwhelmed, she says. Under her hand, 80 Days grew and grew. At the start, she had near-total freedom. The team had built the bones of a world, but were busy finishing Sorcery 2! and needed a writer to steer the ship. “I wrote a mechanical camel race, and they were like, ‘Right, that’s how we want to do steampunk.’”

She used that freedom to its fullest. 80 Days was almost entirely text-based, so if Jayanth wanted to invent a mechanical train with a horse on the front that breathed fire, she could—and did. She spent months researching, drawing on a wide range of sources, including the work of poet and writer Amal El-Mahtar, who had envisaged a “steampunk without steam” in a world where water is scarce.

Credit: inkle Ltd.

Jayanth also wanted to decolonize Verne’s novel, the story of a rich white man traveling the British Empire. Verne had researched every location meticulously, except India, it seemed. He’d never traveled there, and essentially wrote the made-up version of the country recounted by colonizers: the India of, in the words of Inspector Fix, “mosques, minarets, temples, fakirs, pagodas, tigers, snakes, elephants!”

“That can be painful to see that lack of care,” Jayanth says, “and that care is what I wanted people to feel when they played that game, from all over the world.”

Jayanth never played 80 Days in full until the recent Switch release, she says. During playtests, she’d purposefully avoid her own writing, solely visiting locations written by Ingold, and therefore never made it around the world. That’s perhaps why she didn’t realize just how good a game she and the team had created. “I had reconciled myself to the fact it was going to be a game played by eight people.”

It was at the 2014 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco that Jayanth got her first glimpse of how monumental 80 Days could become, a full eight months before Time magazine named it Game of the Year. The inkle team walked into the conference, glanced up at the giant jumbotron, and saw their game scrolling across. “We stopped and looked up at that, then looked at each other. It was just this little game, I’d made it mostly in my pajamas, sitting on the sofa, typing away,” she says. “It was an extraordinary experience. You’ve been working on it in your home without showing it to anybody. It’s like going from a dark room into the light, and you’re blinking.”

80 Days received three GDC Award nominations, four BAFTA nominations and three IGF nominations (winning the Excellence in Narrative award). It wasn’t enough to shake Jayanth’s impostor syndrome—“I still woke up and looked at my blank page and thought, ‘My god, am I going to be shit today?’”—but it was part of a process that made her more proud of her writing.

What she remembers most fondly about 80 Days is its hopefulness. It deals with war and racism, but “there’s very few evil things you can do,” which feels poignant in today’s geopolitical climate. “People are fundamentally good, and that’s something that’s hard to…” she tails off. “I’m trying to keep the faith at the minute.”

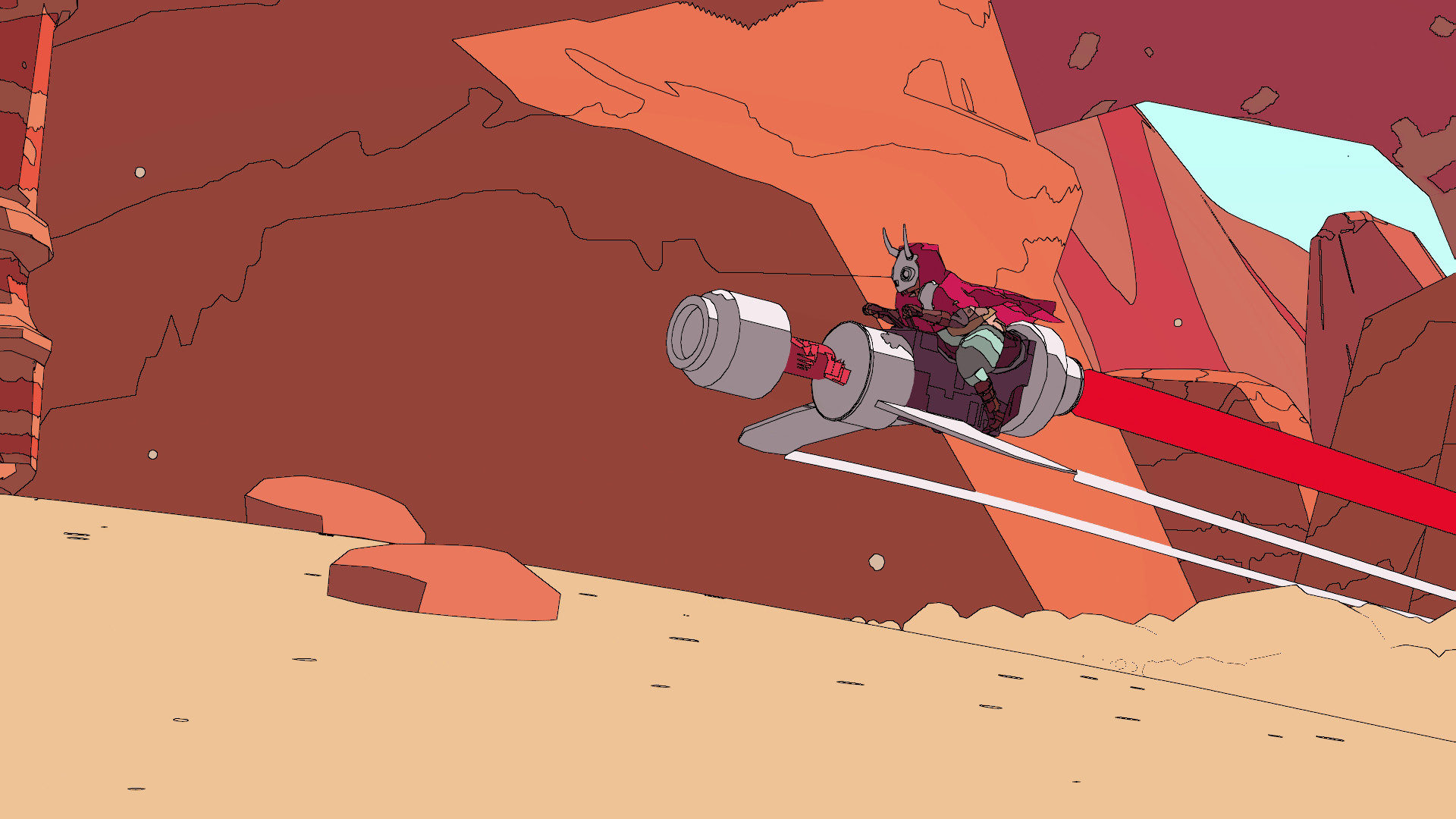

Her inherent optimism about humanity extends to her current work on Sable. Its setting is ancient and alien, and cultural norms shift as you traverse the map. But, in a move that’s almost unheard of, you explore the large open world entirely without combat. “That opens it up to a much bigger audience. I feel like I could put my mum in front of it in a way I couldn’t with a Zelda game, because she’s going to be attacked.”

Credit: Raw Fury

While 80 Days was about being a tourist, Sable is about inhabiting a world and inhabiting a character. It’s part spiritual journey, part gap year: The eponymous protagonist must travel around, talk with strangers, and find her place in society. Ultimately, as is customary in Sable’s universe, she must pick a mask to wear for the rest of her life, one that reflects her chosen clan or profession. When the player chooses a mask, the game ends.

The overarching story is relatively small, and Jayanth says her job is to do “as little writing as possible.” Moments of drama come from smaller-scale stories discovered when players poke their head around corners. It’s a big risk, she admits. “We’re making a bet that we can engage people with a smaller, more emotional story that can still have drama and conflict and humor but doesn’t follow many of the traditional routes to that.” In making Sable’s story about the journey, rather than the destination, Jayanth is railing against an obsession with endings. The sad truth about video game narratives is that very few players see them through to the end, “so the key for me in Sable is a sense of narrative payoff and enjoyment all the way through.” She’s also rejecting blank slate protagonists: Sable will have views and a history of her own, and a personality that changes as the game progresses.

Just as with 80 Days, there exist obvious—and perhaps less obvious—parallels between the lives of Sable and Jayanth. “It’s partly the story of somebody leaving their clan behind, and going out into the world, and maybe being unsure of what they want to do in life. I feel like that’s really universal.

“But I personally am bringing into it my experiences as an immigrant, my experiences as someone brown, the questions: Do you want to assimilate into a culture, do you want to fit in, do you want to leave your past behind, or do you want to embrace it, be proud of it? I don’t think there are any right answers to these questions. Sable is a game of me growing up too, and feeling more like an adult. It’s a game that I’m writing looking back on that period in my life, of where you weren’t really sure about yourself.”

Credit: Raw Fury

Viewed through the right lens, it’s a power fantasy, she says. Sable has freedom to decide her own future, to carve her own path, to choose her own mask. But it’s not a “radical freedom” where players can do what they want without consequences. Despite its modest narrative, choices you make in Sable will have a bigger impact on the world than they did in 80 Days. Actions will have costs, even if that action is standing up for something you know to be right.

It’s a fact of life Jayanth knows all too well. Whenever she stands up for a cause, she’s always thinking: “Is it worth it? Do I want to do this? I’d better lock down my [social media] accounts. And that’s a real shame. You shouldn’t have to self-censor yourself, and I think there’s a lot of that going on. You want to be successful in the industry, but not too successful, because that will draw attention or ire.”

Jayanth weighed those questions when preparing for last year’s Independent Game Festival Awards, which she’d been asked to host. The week before the event, Brenton Tarrant, a 28-year-old man from New South Wales, Australia, had opened fire on two Christchurch, New Zealand, mosques with shotguns and semi-automatic rifles, killing 51 people and injuring a further 49. For Jayanth, the links to GamerGate—the 2014 online campaign that harassed minorities, women, and progressive voices in the industry under the guise of protesting ethical failures in games journalism—were clear. “It felt [with GamerGate] as though we rejected that campaign of hatred,” she said during the award ceremony. “But it’s actually never felt closer to me right now. A mutated strain of that poison that made video games its testing ground has bubbled up in Christchurch, New Zealand. It fueled a monster who went to a mosque with murder in his heart, and if we don’t utterly, and vocally, and wholly reject these people—these Nazis, and fascists, and white supremacists—then we are inviting them in.”

The online abuse was immediate. “The week after, YouTube recommended me a hate video of my own talk—a little indication of the late-capitalist dystopia we live in,” she says. But Jayanth knew it was coming, and therefore “wasn’t very upset at all by the response. Anyone who gets upset when you say ‘We don’t want Nazis in our community,’ is not somebody you want in your community. I found it really bizarre that people would say ‘There are no Nazis anymore’, and come all the way to my Twitter account to say it.” Sometimes, those very same users would have social media profiles full of coded attacks on Jewish people, Jayanth says. “These are not just some people making an off-color remark on Reddit, this is not political correctness… They genuinely hate people who are unlike them.”

More upsetting was the fact people who had supported her were targeted too. “People who were tweeting at me to say, ‘It was so nice to see a brown woman on stage’; anyone visibly of color; anyone who had pronouns in their profile, they were targeted, and got a stream of harassment.” Soon after, at GDC 2019, Jayanth found a Vietnamese sandwich shop she adored, and wanted to tweet about it. But she thought twice, fearing that it would become a target.

The industry is still not doing enough to root out white supremacy, Jayanth says. It still needs to fight the sort of “radical tolerance” she discussed in her IGF speech. Tolerating everyone means you’re tolerating the people that talk the loudest and are the most angry, she argues. “If we want to call ourselves artists, then our responsibility can’t only be to money… Just because these people like your game, does it make it okay? And if that’s your audience, those are the people who are vocal in your community, who isn’t speaking up?”

Making open communities is a process of curation, she says, and “pissing off Nazis is a good thing to be doing. As an industry, it just needs to be okay, it just needs to be something we accept: That is the standard of moral behaviour.”

Jayanth is most encouraged by what she sees in the mid-tier indie space, where companies can afford to curate their communities, get to know their audiences, and create healthy relationships with fans. She’s seen it with a Titanic Storyscape game she wrote last year: Women in their 20s and 30s “making memes and talking about your characters. That to me is really heartening: the sense of broadening in the industry.”

That mid-indie space is also leading on diversity, she says. She saw the effects firsthand while working on Falcon Age, developed by Outerloop Games. The company’s founder, Chandana Ekanayake, grew up in Sri Lanka, and the diversity on the team created an atmosphere where “we didn’t have to make the argument, we could just get on with it.” Jayanth believes the inherent customization in games means the medium can lead the entertainment industry in terms of openness and inclusiveness. It allows people “to see themselves, to have different skin tones, to have a range of love interests that accommodate for different sexualities.”

Jayanth doesn’t reserve her opinions for award ceremonies, interviews, or tweets. 80 Days was feminist, anti-colonialist, and anti-racist, and designed with those messages in mind. It felt fun and subversive. She always wants her work to say something original, or at least interesting, about the real world. It’s deliberate—although much of her writing isn’t, she says.

She doesn’t like detailed outlines and believes games should be at least in part discovered by their creators, not planned. “If there’s too much I’ve decided on beforehand then it feels very paint by numbers to me.” She describes herself as a pragmatic, logical person—but when it comes to her craft, she enjoys a dose of mysticism. On her best days, the words pour out. She gets in a “state of flow,” and six hours flies by. She’ll forget meals, and her friends know she’ll often ignore texts. In this state, she doesn’t have to overthink her writing: she can just be in the moment.

Her mysticism comes with an occasional dislike of what she calls “tinkering.” Her partner is her first reader, and he edits at the sentence level, but if something’s not working Jayanth would much rather throw the whole idea away and start afresh than try to patch it up.

As she writes—which she likes to do at home, alone, rather than in a café—she listens to music that fades into the background, with lyrics that she either can’t understand or are so familiar that she barely hears them. For Sable, she’s listening to Turkish singer Gaye Su Akyol, which gets her in a desert-punk headspace. For 80 Days, it was Kanye West’s Yeezus (I can’t shake the image of Phileas Fogg nodding his head, top hat bobbing in time to “Black Skinhead”).

But while that approach hasn’t changed, the way her work fits into her life has shifted drastically. During 80 Days, filing words at 2 a.m. worked because Ingold, who had just become a father, was invariably still awake. Now, Jayanth avoids late nights and strives for a work-life balance. Weekends, often elusive to freelance writers, have become real.

It took a moment of crisis for Jayanth to change. For years, she’d worked her body into the ground, and put off proper treatment for worsening chronic pain. “I became obsessed with that next short-term deadline,” she says. “I’d been so used to pushing myself and scheduling myself to the point where, if I’m healthy, I can get all of this done. But if I lose a few days to chronic pain… it was stressful falling behind. I think I had to get to a point of crisis to really rethink how I approached work.”

That point arrived in 2018. Doctors had diagnosed her with endometriosis, but her condition worsened despite hormonal medication, and she was regularly suffering from bouts of pain that couldn’t be managed by strong painkillers. “I’d never been unable to hit a deadline before, and I killed myself to do that in the past. But for the first time, physically, emotionally, psychologically, I just couldn’t do it. I had lost my sense of joy in the work.” Jayanth descoped her involvement with numerous projects and effectively took six weeks off, getting on top of her health and rethinking her approach to writing. Now, she exercises more, makes time for a social life, and ensures writing doesn’t overstep its boundaries.

In a sense, she’s lucky she was able to take that time off. Not everybody can afford to, especially those who are early in their careers. The odds, Jayanth explains, are stacked against them, and the industry is built on exploitation and overwork. Developers are taught that they’re only worth their productivity, and that passion trumps everything. “Passion is an excuse for long hours, passion is an excuse for burnout. I think a lot of people came into the games industry because they love games, and it’s so easy for that joy to be taken advantage of,” she says. “It’s a constant battle against that tide, that vortex sucking you into overwork.”

Jayanth sees issues of labor as central to many of the industry’s ills, including the lack of representation for minority groups. For her, improving diversity is more about retention than recruitment: “It’s less important to me that we get more minorities into the industry than it is we treat minorities well, and we change the industry so that it’s not more grist for the mill,” she says.

She also views the abuse of women in games as, fundamentally, a workers’ rights issue, and points to the importance of unionization. “We’re all here to work, and this is all stuff that gets in the way of our work. It’s a shame so many of us in the industry have had to spend so much time clearing up these messes, or navigating around these roadblocks, or certain individuals, or structures, or systems that stop you doing your work and thriving in this industry.”

Last year, after an anonymous Twitter account began naming alleged abusers in the industry, Jayanth accused Alexis Kennedy, developer of Sunless Sea and Cultist Simulator, of exploiting young women, calling him a “well-known predator.” “Alexis Kennedy has a pattern of ‘befriending’ young women who are entering the industry and then crosses professional boundaries with them,” she wrote. “This is exploitative. I know this now because he did this to me, when I approached him as a young woman looking for career advice and work.” Failbetter Games writer Olivia Wood and creative director Emily Short also spoke out against Kennedy, who has denied wrongdoing.

More women came forward to speak about the harassment they’d faced from other developers in what the mainstream press dubbed “gaming’s #MeToo moment.” Jayanth went public, she says, because it “felt like an important thing to do”—it was a way of protecting other people in the industry. “Nobody goes through this, or puts this stuff out publicly, if you haven’t run out of any other way to deal with an issue. It was really about the safety of our colleagues—it felt worthwhile to do that for other people.”

The result of abuse, whatever form it takes, is a loss of talent, which is bad for both studios and players. A single instance of abuse can be devastating, she says, because it makes people feel like they’re not good enough. “I had a lot of people share their stories with me, which was amazing and saddening—powerful, in a way. But what I really heard over and over that their presence was not wanted, that they weren’t good enough. And that’s so often not the case.

“I think there isn’t enough of an understanding still about the power differential. I think a lot of these stories have been about older men in positions of mentorship over younger people. It’s hard to overestimate how powerful a position that is. I know personally people who have, many women and minorities largely, who have left the industry because of terrible experiences they’ve had, for various reasons. This is a huge loss of talent: many incredibly talented people who are either no longer writing or no longer in the industry altogether.”

The stories that came out last year were just the beginning, she says: a foundation from which the industry needs to build. “I know there are so many more stories of say, abuse and exploitation in the industry, where people don’t feel able to say anything about it, but I do think that’s changing… I think it’s people that have power, and people who are less worried about retaliation, that’s where it needs to come from.”

Jayanth can now count herself among that group with power. It’s a power earned through her actions and words, through activism and through work. From Samsara to 80 Days she built a reputation. Sable reflects her growing up in the industry. And after Sable comes Red Queens.

When Jayanth first met her Red Queens partner, Leigh Alexander, in 2015, they had an instant connection. “I cried, she cried. It’s one of those Thursday evenings at GDC.” By the fourth time they met, Alexander was flying out to India to stay with Jayanth’s family.

Red Queens, announced last year, won’t kick into gear until Jayanth finishes work on Sable. Initially, the pair will likely consult with other developers on existing projects where they can have a real say in the direction of a game, twisting established universes in unexpected ways, in the same way the recent Watchmen TV series did with the original 1980s comics. But ultimately they want to make their own games. Jayanth wants full control over her work.

“What’s really exciting about Red Queens is there’s so many ideas we have, and it’s suddenly opened up a new avenue. The big thing is having creative control. We’ve both learned a lot in the industry and we’re both ready to find that next level.” They already have one game of their own in the works that Jayanth can’t discuss, but she does talk about her love of romance games, of episodic stories, and of mobile gaming. “I’ve always loved dating sims. I’m also a huge BioWare fan… that mashup of interactive fiction meets simulation game meets romance. We both really love genre, so I think it will be really exciting to do interesting, surprising, subversive genre work that’s forward thinking.”

She also wants to reach a more contemporary audience: the kind of players that might’ve been put off by the heavy steampunk elements of 80 Days, for example. Red Queens’ games will be “mechanically sophisticated, drawing players in with concepts, settings, that are more familiar to them.” In a nutshell, it’s “games made for people who aren’t maybe ‘core gamers.’ There’s loads of stuff out there for core gamers. But gaming is mainstream now. There are all these non-traditional gamers in the mainstream market, and we’re committed to serving that audience with quality and respect. We were that audience as well.”

Launching her own venture is “terrifying,” but the trials of the past few years have prepared her for it. “The scrutiny last year was hard, but it felt a little bit like trial by fire. Once you’ve been through that fire, you know yourself, you know what you stand for, you know what you want to do. It feels like growing up in the industry… It’s been a process of letting go of that impostor syndrome. And now, embracing the idea that, actually, we have something interesting to say.”

In other words, Meghna Jayanth has found her mask.

Header image credit: Credit: Darren Salanson for EGM

Samuel is a freelance journalist. When he first played TF2, he couldn’t work out how to fire his gun—until he read a troubleshooting guide. You can find him on Twitter @SamuelHorti.