At GDC in March, Google CEO Sundar Pichai took the stage and spoke at length about how the company’s employees love to solve hard computer science problems. He boasted about the DeepMind AI’s prowess for mastering games like chess and shogi, AlphaStar’s success against StarCraft II pros, and how they developed scalable simulations for their autonomous vehicle technology.

It was the preamble to the unveiling of Stadia, a cloud-driven service that aims to cut out the requirements of a owning beefy PC or home console to play video games. The initial presentation was scant on specifics. A number of concerns—from stability to data caps to input latency—materialized across the internet soon after the reveal.

In June, Google hosted another presentation with more details. A subscription-based service will allow users to stream games at 4K resolutions and 60 frames per second. This subscription will also include a limited selection of games. Consumers who instead opt to use the service without paying a recurring fee can stream games at up to 1080p, but this free version will not be available until after launch.

Phil Harrison, vice president and general manager for Google, confirmed in a series of E3 interviews that the price of games on Stadia will be the same as they are on other platforms, and that he expects ISPs to solve data cap concerns.

Credit: Tequila Works

The June presentation answered some questions surrounding Stadia, but others remain. What will happen to a customer’s digital library of games if Google eventually decides to discontinue Stadia? Given Google’s history with pulling support for their products, it is a fair concern.

Like a rainbow trout, the average lifespan of a Google product is just four years according to Killed by Google, a website which purports to be a graveyard for Google apps, services, and hardware. At the time of writing, the website has catalogued nearly 200 products that have been shut down or have a finite amount of time left.

“I know that in 10 years from now—assuming my Switch is still working—I can put a cartridge in and it will run that game,” Cody Ogden, the software developer who created this digital cemetery for Google products, told EGM.

In a bit of irony, Ogden and I had a lively conversation using Google Hangouts, which will not be around for much longer. An epitaph on Killed by Google reads, “Done for in 3 months, Google Hangouts was a communication platform which included messages, video chat, and VOIP features. Execution date is tentative. It was over 6 years old.”

Ogden said that he created the site over a weekend and received help from GitHub contributors during Hacktoberfest, a festival for open source coding, and that it really took off around the time of Stadia’s reveal. He is hesitant about playing what he called “the prediction game,” but was not brimming with confidence about the prospect of being able to access his Stadia library in 10 years as easily as he can access his physical Switch library.

Credit: Ubisoft

Ogden has been using Google products for 10 to 15 years, by his estimate. Scores upon scores have come and gone. He was a power user of Inbox by Gmail, which shut down this past March, much to the consternation of its users. The unceremonious shuttering of the service was what initially sparked Ogden to make Killed by Google. Losing Inbox represented an enormous hit to his personal and professional productivity.

While the loss of a product like Inbox was an inconvenience, the loss of a social networking and chat app called Meebo marked something more personal for him. He made friends and cultivated relationships over Meebo.

“Now I have no way to reach them now that that community is disbanded,” he said. “Having that go away was very stressful. It was like, ‘How am I going to stay in contact with these people. I’m just gonna lose them.’ It’s not the technology itself, it’s the way I was communicating with people behind the technology.”

Others, like Justin Gray, have been burned before in the primordial fire from which services like Stadia emerged. In Gray’s case, it was OnLive, a cloud gaming service founded in 2003, which finally went defunct in 2015. Gray accrued a modest library of games that went up in smoke overnight.

“When OnLive shut down I lost access to all the games I bought, and there was really no recourse of getting my money back,” he said.

Gray said that he would have been happy had they simply offered him an executable file or Steam keys for the games that he suddenly lost access to, but that was out of the question. This experience has not inspired confidence in him towards Google’s latest product.

“So if Google’s Stadia somehow shuts down, or if Google decides Stadia isn’t making enough money and shuts it down, anyone who buys games on there might be shit out of luck,” he said.

According to Gray, what would assuage some of his doubts would be for Google to confirm that, if Stadia goes “belly up,” customers will retain access to their library in some form.

Credit: Coatsink Software

Alex McCumbers, co-creator of Forever Classic Games and contributor to the SNES Omnibus books, is likewise concerned about the lack of concrete details on the matter from Google. He reached out with a statement:

“Stadia has one major problem, unclear longevity. Games exclusively launched on Stadia run the risk of being lost to time due to the online-only nature of the platform. Until there’s some sort of ability to download DRM free games or use physical media, all of Stadia is temporary until proven otherwise and therefore lacks the value of a typical game purchase.”

Others are slightly more optimistic, like Reddit user Eagle736. “Given the money and time invested for Google to enter the gaming industry, I don’t see Stadia being a platform they will be as fickle with.” Still, it has to be acknowledged that sentiments from most consumers who I spoke with were far more skeptical.

For instance, one individual I chatted with, who preferred to go by his initials, C.W., said, “The average lifespan of a Google service is 4 years and 1 month. I think that sums up most people’s concerns pretty succinctly.… I have games on Steam I bought nearly a decade ago, and I don’t think they’re going anywhere. I would guess if I ‘bought’ a game on Stadia it would be gone in 4 years.”

It is unclear whether or not Google will provide a remedy to consumers if Stadia eventually goes the way of 171 (and counting) of its other services.

As first reported by 9to5Google, the official FAQ page for Stadia was updated early on in July. Although none of the updates mentioned this specific concern—that of Stadia shutting down completely—one answer does now promise that games will remain available in consumers’ libraries even if they’re pulled from the store subsequent to purchase.

I reached out to numerous developers who are working with Google to get their thoughts on this, but each and every one either declined to comment, citing being bound by strict NDAs, or never responded at all.

Google also declined to comment.

Header image: Google via EGM

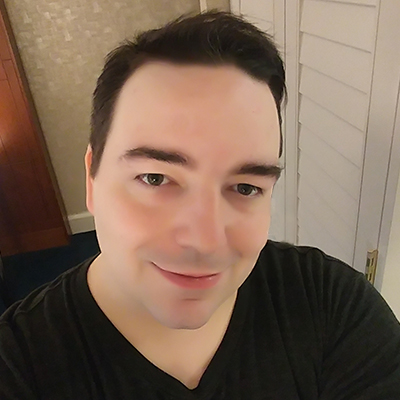

David O’Keefe is a freelance journalist and photographer who smiles at the very mention of leopard geckos or Warcraft 3. He studied journalism at The College of New Jersey in his home city of Trenton and was taught photography by the Pulitzer-winning John Filo. As a result of his struggles with depression and social anxiety disorder, David has also become a vocal mental health advocate. He covers games, esports, tech, and entertainment. Follow him on Twitter @DaveScribbles and peruse his portfolio on Muck Rack.