Giant mechs do not make the slightest bit of military sense. A 10-meter, 75-ton behemoth that plods onto the battlefield in full sight of every enemy before it might as well wear a “Place Artillery Fire Here” sign—assuming the pointlessly complicated machinery is even functional on the day of battle. But if you can accept the conceit on the basis of “giant mechs are awesome,” BattleTech is one of the more storied franchises to embrace the idea.

BattleTech launched in 1984 as a tabletop wargame called BattleDroids, before George Lucas’s lawyers suggested a name change. It grew to encompass novels, RPGs, collectable card games, multiple video game genres, a long running MUD, piles of fanfiction, and a terrible cartoon. The franchise has gone through fallow periods that included bitter legal battles, confusing ownership changes, and droughts of new content, but now it’s once again experiencing a boom. In 2019, Piranha Games released MechWarrior 5: Mercenaries, the first single player MechWarrior game since 2002. Last year also saw Harebrained Schemes’ turn-based BattleTech release a wave of strong DLC, while a Kickstarter for a tabletop expansion raked in a staggering $2,586,421.

The primary appeal of BattleTech is of course the BattleMech fights, whether they’re in the form of dice-based tactical struggles or a twitchy arcade shooter. But a franchise doesn’t last this long without a deeper draw, and there’s something about the setting that speaks to its fans. As a crash course for the unfamiliar, most of the actual gameplay and fiction occurs between the 28th and 32nd centuries, but the story traces back to the politics of 1980s that created it. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 2014 and the creation of the fusion engine in the futuristic year of 2020, humanity trends towards united governance and begins to take to the stars. Thousands of planets are colonized and, after some bumps, scrapes, and war crimes along the way, the Star League is formed. Essentially an interstellar United Nations, the League ushers in two centuries of relative peace and prosperity, a social and technological high-water mark for the species.

Then everything collapses, because the games aren’t about using mechs for peaceful construction projects. By the time players enter the story, prolonged civil war has sent the galaxy on an extended scientific backslide and locked five major powers in a perpetual cold—and often hot—conflict. These interstellar nations, dubbed the Great Houses, have also slid backwards into various forms of neo-feudalism where titles can provide more power than votes and a ruler’s authority on what happens far from their throne is often just theoretical. Most of the creators and fans interviewed for this piece compared it to Game of Thrones, in which political decisions are made by lords and merchants, battles are fought by knights and mercenaries, and everyone else just wants to get on with their lives. It only gets more complicated from there.

Credit: Paradox Interactive

For a franchise about giant mechs waging war a thousand years from now, BattleTech has a decidedly human touch. It’s not the admirable but perhaps unattainable utopia of Star Trek, the magical and faraway moral fable of Star Wars, or the emotionally sparse and chronologically distant cartoon dystopia of Warhammer 40,000. Aaron Falcone, who runs the BattleTech YouTube fan channel Death From Above Wargaming, explained that the setting feels connected to today’s world.

“I think the big thing that draws people into the BattleTech universe is that it’s relatable,” Falcone said. “There are no crazy aliens, outrageously infeasible technologies, or game-breaking magic. It’s a very real-adjacent extrapolation of the world we live in today. Almost all of the factions have unique flavors which are traceable back to the various ethnic roots of countries we know and understand. I also love the persistence of modern day companies like GM, Nissan, and Boeing.”

In BattleTech, GM still creates vehicles for war and industry, Boeing dropships soar through the stars, and Nissan engines power BattleMechs. One major power, the Federated Suns, demonstrates BattleTech’s syncretic approach to humanity’s future. A constitutional monarchy that evolved out of Great Britain’s political traditions and still employs an intelligence agency named MI6, it nevertheless contains as many Buddhists as Christians and also features large Islamic and Hindu enclaves. Over in the quasi-American, capitalism-loving Free Worlds League, English is the official language, but if you have serious business aspirations you should probably pick up Czech, Urdu, and Arabic, too.

It is, in its own way, an optimistic view of the future of human tolerance and cohabitation. But the individualistic Free Worlds League tends to paralyze itself with constant indecision and infighting, while the scientific and military might of the Federation makes it prone to an arrogant refusal to examine its own flaws and acknowledge its systemic rot. In the authoritarian mix of Han and Maoist China that is the Capellan Confederation, all citizens are offered the finest public education and healthcare in the galaxy, but they can also be pressed into slave labor for displaying cowardice or disloyalty. It’s a universe fascinated by unforeseen consequences and the flaws of well-intended ideas, and one that suggests that putting aside our differences, while admirable, will ultimately only make us seek new differences.

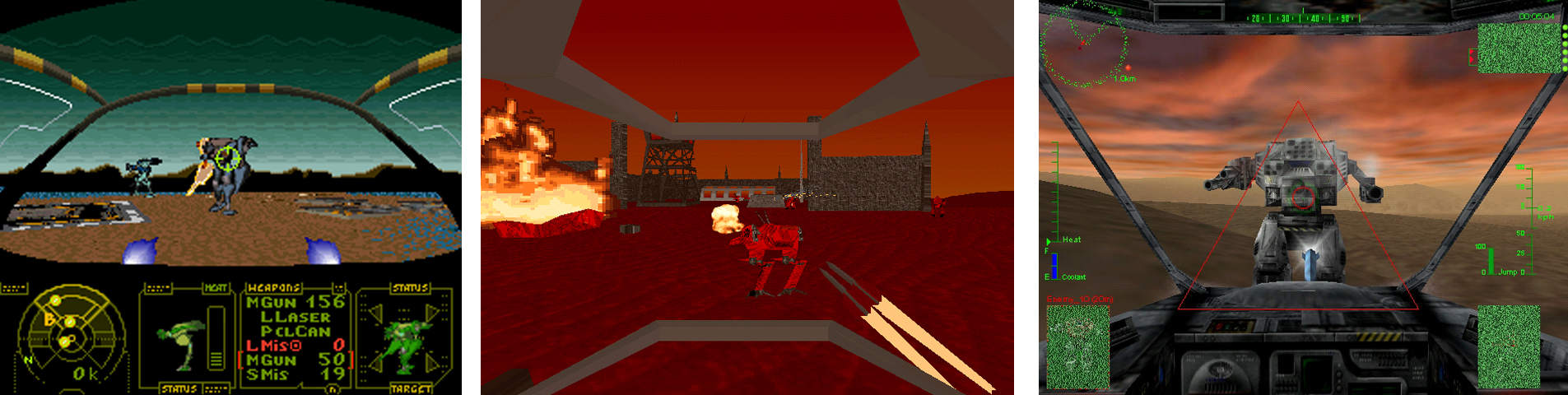

Credit: Activision (left screen via MobyGames user Mobygamesisreanimated) and Hasbro

BattleTech’s perpetually gray morality can make for a compelling gaming backdrop. As Insaniac99, moderator of the BattleTech subreddit, explained, “When I was little, it was, ‘Ooh, pretty mechs,’ but after growing up and learning more I love how deep the lore is. It feels like a living, breathing universe. People make mistakes and do things that from the omniscient perspective doesn’t make much sense, the Mech designs aren’t all perfect because there were [resource] shortages. All of that detail is there to find if you want to dive deep. At the same time, there is still plenty of room for your own RPG group to fit in and interact with the world and create your own stories.”

In a clever narrative trick, the horrors of unrestrained warfare prompted the galaxy’s powers to agree to conventions that codified war as something that could be fought with relatively little destruction, but that also inadvertently made it an attractive choice for solving most disputes. Some conflicts are still large and devastating, but most core planets will never be touched by war and many planets on national borders and the periphery of human space—the focus of much of the games and fiction—see their fates decided by a couple dozen mechs fighting on the outskirts of town, after which the residents might have to change their flags but not much else. It’s the drama of warfare without (most) of the war crimes and thus, to the player, the joy of blowing up buildings without the worry of whether there were civilians inside.

BattleTech also has little interest in racial or gender strife. One of the deadliest MechWarriors in its history was a woman who fought into her 80s, and a millennia of heterogeneity has produced characters with names like Renauld Yamaguchi, Xerxes Cunningham, and Abraham Chi-Li. BattleTech wasn’t immune to the stereotypes of its time—early novels featured zealous Arab warriors, scheming “yellow peril” villains, and token women warriors who oozed sex appeal—but it did try to rise above them. In a winking nod to its own tropes, a later novel mentions a red-haired, green-eyed Rabbi Martinez whose only trait is his unremarkability. HBS’ BattleTech attracted trolls for its non-binary character creation options, but that flexibility fit the spirit of the games. Any kind of person can achieve power and respect in the BattleTech universe, with the interesting question being how and for what purpose.

As Falcone pointed out, this gives players a storytelling investment without overwhelming them. “The lore is an amazing backdrop. It gives meaning and purpose to every battle we play, because there is more at stake than just capturing some random planet,” he said. “There are these great personalities, both heroes and villains alike, all of whom have motives that are believable. But the story is never so overwhelming that it feels like a soap opera. There is, quite literally, something for just about everyone. Personally, I will always be a mercenary at heart. I’ve always liked the notion of creating a little unit and rising to fame and glory.”

Most players get attached to certain factions, be it for storytelling reasons or because they like the iconography. But the mercenary perspective is so common in BattleTech that it’s arguably the default setting, with both MechWarrior 5 and HBS’ BattleTech using it a launching point to tell two very different stories—one about avenging the death of the player’s father, the other about the risks and consequences of getting embroiled in a minor power’s civil war. In a fictional setting where perpetual peace would end the games, there’s always the risk of falling into a bleak grimdarkness that numbs players. It can therefore be compelling, as Piranha Games president Russ Bullock explained, to use the perspective of someone who just wants to get their bills paid for another month.

“[It] makes for a great playground. For the most part you don’t care about any particular political faction, it’s all just work,” Bullock said. “In MechWarrior 5 we were able to use this to our advantage. We have the player doing countless morally gray objectives, sometimes running assassination missions against one faction’s political enemies but then perhaps switching factions later.”

While MechWarrior 5 isn’t as story-focused as other BattleTech games, that mercenary approach does give players the freedom to tell their own tales.

“It speaks to people, it always has,” Bullock explained. “My favorite past MechWarrior titles were MechWarrior 2: Mercenaries and MechWarrior 4: Mercenaries. I don’t think it’s the story where they have the advantage, I think the non-mercenary versions have had the edge there. I think it’s all about playing out your fantasy of having the freedom to go and do what you want. The past titles kind of played on the edge of allowing you to do that. But MechWarrior 5: Mercenaries was really an attempt to deliver what everyone wished they could have the freedom to do in those past titles.”

Credit: Piranha Games

BattleTech leans far more towards fun escapism than it does serious political commentary. But it does feel like a political franchise in its own way, given that the running theme of much of the series’ output is “arrogant elites who crave more power will scheme to throw the galaxy into chaos.” A typical BattleTech villain is one who’s found a way to abuse their systemic power, to lie and manipulate with such efficacy and ruthlessness that no ponderous appeal to bureaucracy and tradition can stop them. That can be depressing, but it can also be a relatable chance to explore how regular people—proxies for the player—respond to the madness engulfing them.

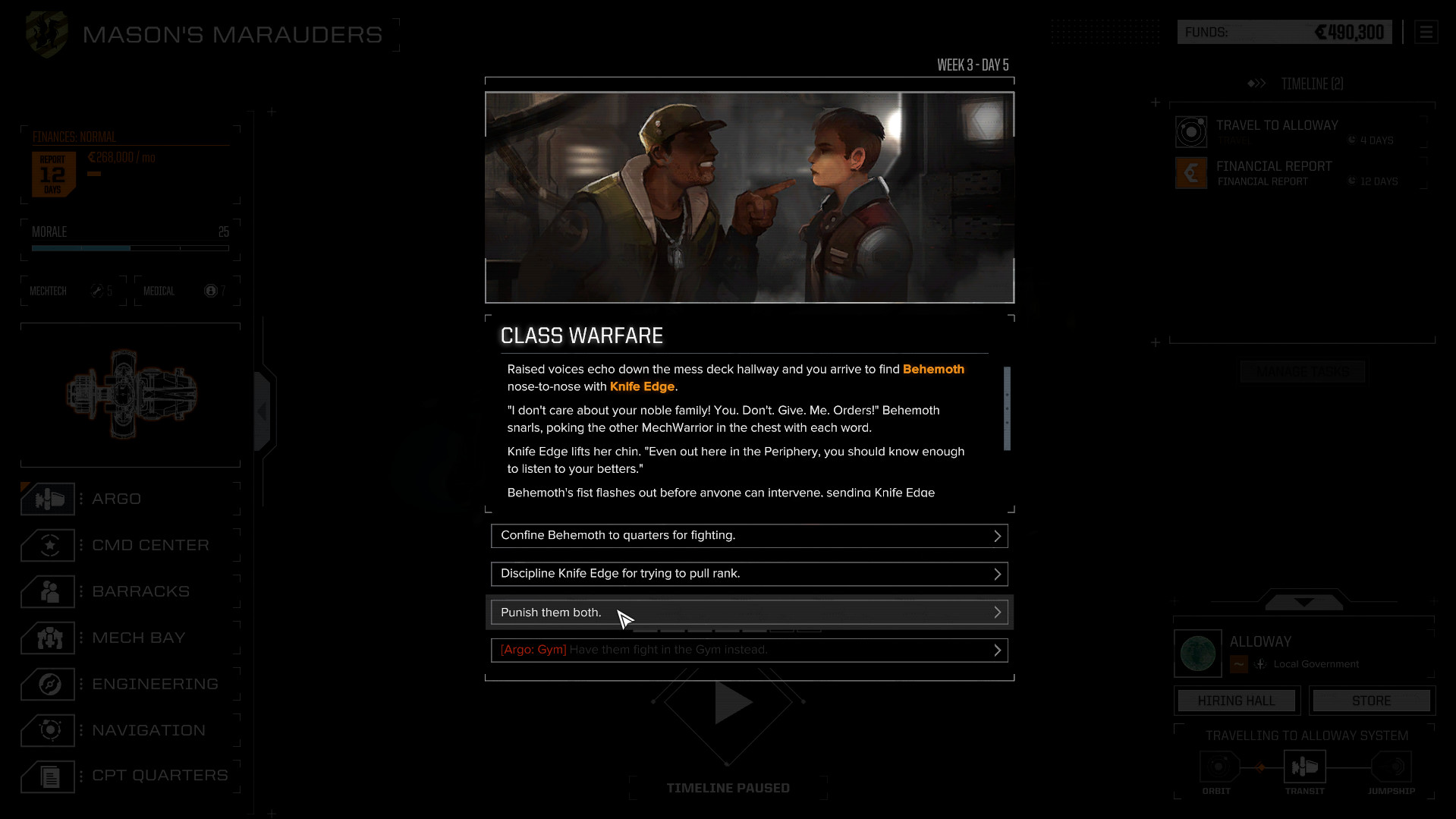

“The stories are very human stories dealing with corruption, greed, betrayal, and nobility,” said Mitch Gitelman, the co-founder of Harebrained Schemes. “In the campaign [of HBS’ BattleTech], we [focused] on a leader learning how to lead, how to make decisions for the greater good, and learning from her mistakes. Our story was about hope and growth. In our three expansions, we varied the tone to illustrate the wide varieties of personalities and conflicts that the setting has to offer. Those ran the gamut from personal stories of estranged mothers and daughters, interstellar governments vying for experimental technology, drunken mercenaries badgering nobles, and artificial intelligences trying to fulfil their programmed objectives. The [mini-campaigns] could be funny or heart-breaking or thrilling or disturbing and still be clearly identified as products of the same broken civilization.”

Gitelman also commented on his team’s use of the mercenary perspective, saying, “I think there’s a real appeal in being an independent actor able to navigate government officials, arrogant nobles, and the scum of the universe. Han Solo has endured for decades for a reason.”

Harebrained Schemes’ BattleTech is full of cute little bonding moments, whether it’s a crew movie night, a game of poker for the senior staff, or your grizzled warriors being caught skinny-dipping. Even the fact that your character can get roped into a game of basketball (rather than the common sci-fi approach of inventing a ridiculous futuristic stand-in called, say, blargsball) helps keep a human touch on a profession that deals out death and destruction. “[We remind] ourselves and the audience that we’re telling stories about people who command companies of BattleMechs, who pilot BattleMechs, and whose lives are affected by the use of BattleMechs for good or ill,” Gitelman said. “Our themes are human themes: families separated by political differences, friends who must forsake their birthright to do what they believe is just, leaders compromising their integrity for power or to defend their people in a no-win situation.”

Credit: Paradox Interactive

BattleTech is also a human look at the post-apocalypse, as co-creator Jordan Weisman has said that the optimism surrounding the steady march of new technology in the 1980s inspired a universe that was sliding in the opposite direction. LosTech—advanced technology that is either literally missing or desperately kept functional without anyone understanding the science behind it—plays a major role in establishing the setting, inspiring conflicts, and giving factions a future to aspire to via a past they want to reclaim.

Jackal-Noble, who mods the MechWarrior 5 subreddit, explained the appeal of seeing BattleTech’s timeline move through different technological eras: “It’s definitely a combination of the dystopian feel [and] that idea that there’s some lost advanced technology waiting to be discovered. The [desire to upgrade our technology] also works pretty well within the BattleTech universe, and is one of the reasons I like it: there’s always an improved version of some weapon or component.”

Early tabletop editions of BattleTech portrayed mechs as invaluable family heirlooms passed down for centuries and requiring nonstop patchwork maintenance from a small army of technicians who barely understand them. Even as the timeline progressed and the technology to build mechs was regained, complicated components were valuable enough to make battlefield salvage a potentially more lucrative payment than cash. The mere hints of an old technology cache can inspire wars, and there’s such a nostalgia for the past in the BattleTech universe that one mission in HBS’ game sees you sorting out a squabble over a Star League–era office supply depot.

But it’s not the apocalypse of Mad Max or The Walking Dead, where an overrun humanity huddles in the ruins and barely clings to their miserable lives. There are planets where scavengers eke out a living with technology worse than ours, and there are planets where elite research institutions thrive thanks to generous government funding. Life just goes on. Or, as an in-universe comedy jokes, this is an era where you can fly across the stars to a planet where you’ll need a donkey to get anywhere, where a farmer can’t use a labor-saving agriculture bot because no one can find or make a crucial 6 centimeter cable. Messages from across the galaxy can take days to arrive, supplies can take months, and one planet can be in whatever condition is needed to justify a good story.

Credit: Activision via MobyGames user NGC 5194

BattleTech doesn’t see failed states and resource shortages as creating rampaging cannibals and (nothing but) evil warlords, but as forcing flawed people into making difficult decisions. Sometimes their ill-conceived solutions backfire, but sometimes their actions help people band together and rise to the occasion.

An unevenly distributed future—and one where there’s both an obsession with the past and hints that the past was never as great as people think it was—is a fertile ground for storytelling, as Bullock explained. “As a child of the ’80s I have always been surrounded with nonstop technological innovation and the pace just seems to never slow down. Some of that is coming with negative consequences in the real world. But in this universe, to see technology decay and fade is a fascinating concept. I don’t think we could ever imagine our technology going backwards or losing what we already have.”

Much has changed since the ’80s, and Insaniac99 noted that “[s]ince BattleTech first came out, much darker sci-fi universes have been made that make BattleTech look positively optimistic by comparison.” Still, inequality is an eternal theme that gives creators and fans extensive options for playing with BattleTech’s history and politics, like Falcone does.

“The creative touches are definitely a big deal to fans, and we love pulling together a compelling story. Many of the fans are amazing painters, modelers, writers, and artists. I think we all appreciate a story that adds emotion and intensity, from the mystique of a location or the legend of a specific pilot,” Falcone said. “When there’s an arc, it’s not just a game of scoring objective points anymore. It’s about rescuing an intelligence officer from an internment camp, destroying a critical listening post as an essential first step for a larger invasion, or just claiming a moral victory by killing off an arch-nemesis.”

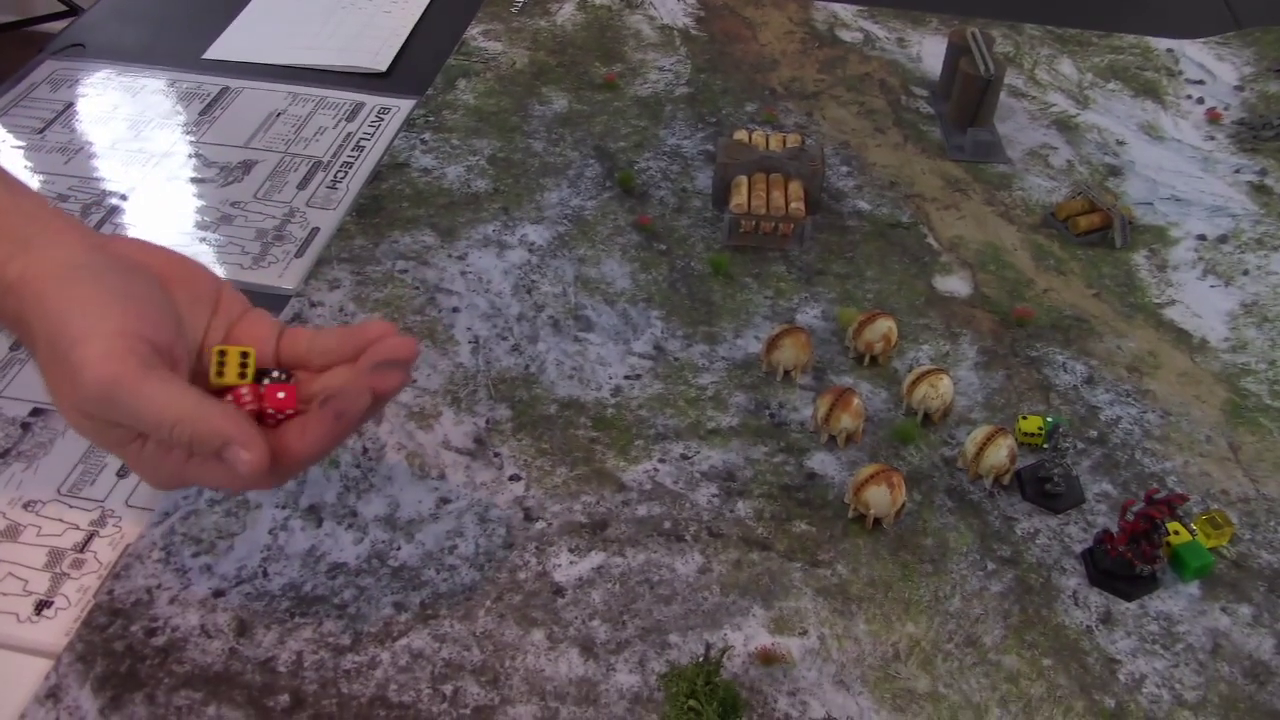

Falcone’s channel is an example of the fan projects that are helping sustain BattleTech’s renaissance as much as the games themselves. The bulk of his videos are breakdowns of tabletop battles presented in loving detail, with one hour-long video taking him and his co-hosts as many as 14 hours to put together.

Credit: Still taken from Death From Above Wargaming’s YouTube channel

“We were hardcore Warhammer 40k gamers, then 40k went through like three editions in two years and we lost a little interest in the churn,” he said. “And then I found myself digging through my dad’s basement for my boxed-up BattleTech collection. Having come from 40k, I was used to an oversaturated YouTube market with some very high quality influencers. But there wasn’t much available for BattleTech in terms of tabletop reports. It was an opportunity to contribute to something I love. In light of the already in-progress BattleTech renaissance, it seemed like the perfect time to get something started.”

Other fans have assembled Lego mechs, dived into the lore with Ken Burnsian zeal, and converted spare bedrooms into cockpit simulators for their grandkids, while the games themselves have been tinkered with by a plethora of dedicated modders. RogueTech takes HBS’ already challenging BattleTech and cranks it up a few notches to punish veterans for the slightest misstep, MechCommander: Darkest Hours revitalized the hefty 1998 real-time tactics game into an epic-length experience, and MechWarrior: Living Legends has offered over 11 years of free PvP combat using a total conversion mod of Crysis Warhead.

But perhaps the BattleTech fandom’s single most impressive project is Sarna, a news site and meticulously organized, 28,695-article-strong wiki. Fans can study up on, and get lost in, information on everything from various laser manufacturers to the planet of Old Kentucky. If you Google anything related to BattleTech, Sarna will be among the top results. Its founder, Nic Jansma, said he “found the game via the big stompy ‘Mechs, and stayed for the lore. There are a lot of amazing franchises out there with rich histories. I would argue that BattleTech is right up there with the best of them. There’s just so much to uncover—so many factions, worlds, eras and battles. I was getting into software development and BattleTech inspired me to share everything I was finding about it [online].”

Sarna launched in 1994 as a GeoCities page before evolving into a wiki in 2006. “The community ran with it and has made it the amazing resource it is today,” Jansma said. “We have hundreds of writers that write thousands of articles a year. Everyone has their own interests and specialties and because of that we have a pretty well-researched, reliable, exhaustive source for every BattleTech nerd.”

Credit: Microsoft Game Studios (via MobyGames user Zovni)

Jansma’s current passion is Sarna’s Planets Project, which wants to provide accurate physical information on the thousands of planets that make up BattleTech’s setting. “We’ve been rebuilding the planetary maps with a tremendous new amount of detail, and have been auditing the coordinates to generate accurate distance tables. It’s just one part of the site, but it’s fun seeing it improve over time.”

As for how someone can dive into BattleTech and end up most interested in its planetary backdrop, Jansma said, “One of my favorite books when I was younger detailed all of [BattleTech’s] planets, their stats, and histories. When I was trying to come up with a ‘cool’ name for my website in ’94, I browsed it and Sarna just stuck out. It must just be my brain. I love maps, atlases, encyclopedias. I wanted to recreate something like a planetary atlas for the first versions of Sarna.”

If every fan gets attached to a different element of BattleTech, everyone also has a different story about how they got into it. Falcone spent hours as a kid perusing sourcebooks at his local gaming store before saving up enough money to buy the base set. He joked that in college he “basically majored in MechWarrior 4. That game, the people I met, and some of the intense matches we played are etched into my soul.”

Jansma learned about the franchise through a BattleTech Center, one of dozens of physical locations dotted throughout the United States and Japan that hosted closed cockpit simulation pods complete with joysticks, pedals, 32 blistering megabytes of RAM and, for some reason, Jim Belushi. They were considered groundbreaking at their 1990 launch but antiquated by the time they began closing in 1995, and only three still cling to life today. The other pods are in the hands of private collectors or were scrapped, ironically becoming LosTech themselves. In a 1992 clip for Discovery Channel’s Beyond 2000 series, a woman in a very ’90s outfit pretends to be a 31st century newscaster.

“My family would vacation in Chicago each year and I would always beg my parents to let me play a few games,” Jansma said. “For the era, the cockpits provided an amazing immersive gaming experience. I remember seeing a demo of the board game at the check-in counter, and I asked my mom if I could get a copy some day. My hunger continued when I picked up sourcebooks, and I started getting deeper into the novels as well. [They] were the main series I read in my adolescence.”

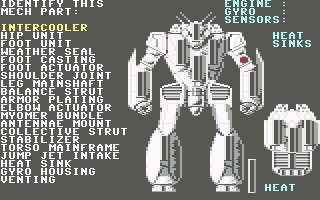

Credit: Infocom Inc.

Insaniac99 and Jackal-Noble both had their first experience with Westwood Studios’ The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, a 1988 title that was BattleTech’s first video game. Both found it too complicated for their young age, but still enthralling. “I had no idea how to play but was absolutely fascinated by the detailed mech diagrams that came in the manual,” Jackal-Noble said. “A few years later and I was enthralled with the graphics on the isometric Sega Genesis game.” From there he became a “hardcore digital BattleTech fan.” Insaniac99 eventually “dove headfirst into the deep end of the tabletop world and started consuming as much as I had the time for.”

All of these different paths speak to the breadth of the lore, but they also speak to the lack of a definitive canon. With no clear starting point akin to the Star Wars movies, and video games that assume a moderate knowledge of the franchise, newcomers can be overwhelmed. HBS’ BattleTech took an admirable crack at the problem with an opening cinematic that introduced the setting. “We didn’t include an encyclopedia of terms that could distance new players,” Gitelman said. “Instead we relied on contextual tool-tips to give players additional context if they were interested.”

Those tooltips were smart, but some reviewers still found themselves struggling to tell a Magistracy from a Concordat. Bullock’s team approached MechWarrior 5 differently, with a focus on ensuring that the game felt fresh and expansive to veterans, but he admitted that hooking new players with an accessible game is “still an unsolved problem.” Then there’s the tabletop game, which can be a lot of fun but can also be a lengthy, dice heavy, Byzantine labyrinth of rules that looks dated to newcomers spoiled by a far wider choice of board games than was available in the ’80s.

Credit: Paradox Interactive

Fans are thrilled by how much BattleTech content has been released recently, but there’s also some concern about keeping this boom sustainable. The BattleTech experience is one that’s divided across mediums, eras of the game’s lengthy story, and varied rulesets. How do you attract new fans to a franchise with a great strength—36 years and counting of varied content—that’s also its greatest barrier?

“Classic BattleTech is a complex simulation game that, in the age of internet gaming, is not terribly appealing to younger generations. It has a really loyal following, though, which makes for a difficult problem to solve,” Falcone said. He suggested “[t]aking a hard look at the rules and offerings in the context of keeping the franchise alive, not through the lens of ‘we’ve been doing it this way forever.’ Get rid of the dead weight. Streamline.” While there are no formal insights into BattleTech’s fan demographics, anecdotally the community skews older and towards white men. The novels that can best explain the piles of terminology and best highlight the setting’s diversity are rarely prioritised and often clumsily written. It’s a welcoming fandom, but a challenging one.

That BattleTech’s ownership is a convoluted split between Microsoft on the digital side and Topps on tabletop has caused licensing messes that have perhaps also hindered chances to grow. The division makes an already complicated franchise seem to lack one clear hand on the helm. Still, the future looks as bright as it ever has, with Jansma noting that Sarna traffic spikes whenever a new game is released, as “new players come to explore the universe they’re playing in.”

Jackal-Noble thinks that, like the setting’s mechs, BattleTech’s best potential is in becoming generational.

“BattleTech is and always was a niche franchise, being the bastard love child of anime robots blended with Western style,” he said. “One of the beauties of the BattleTech universe is that it is a very open, inclusive setting. I would like to imagine the latest games will result in parents teaching their kids the game, inspiring a new generation.”

Header image credit: MechWarrior 5: Mercenaries / Piranha Games

Mark is an editor and columnist at Cracked, a regular contributor to Macaulay Culkin’s Bunny Ears, and has written a novel you can check out here.