In 2014, the whistleblower Edward Snowden spoke with German broadcaster NDR about a National Security Agency tool known as XKeyscore: “a front end search engine that allows [the NSA] to look through all of the records they collect worldwide every day.” According to Snowden, someone with access to the system “could read anyone’s email in the world. Anybody you’ve got email address for, any website you can watch traffic to and from it, any computer that an individual sits at you can watch it, any laptop that you’re tracking you can follow it as it moves from place to place throughout the world.”

Six months earlier, the NSA had issued a press release in response to the publication of classified materials leaked by Snowden. This statement painted a much different picture, assuring the public that tools like XKeyscore “have stringent oversight and compliance mechanisms built in at several levels. One feature is the system’s ability to limit what an analyst can do with a tool… and no analyst can operate freely.”

The scariest thing about Telling Lies, the new political thriller from Her Story creator Sam Barlow, is that it takes the NSA at its word. You play as an unidentified woman using a fictionalized version of XKeyscore to access a stolen database of video recordings obtained through NSA surveillance. Retina, as the fake database is called, offers only extremely limited search functionality—a necessary precaution to protect the privacy of those whose data is collected, according to an in-game document.

Accessing as many videos as possible so you can piece together the full story is an exercise in working around these constraints. Clips can only be accessed by entering specific words or phrases spoken by the people in them, and to prevent abuse of the system by inputting common words, only the first five results are displayed for any given query. (This much should sound familiar to anyone who’s played Her Story.) You can also search directly from a video by highlighting a word or phrase in the subtitles while paused, which is cool in practice but functionally useless if you want to watch each clip in full. In two-way video calls, which make up the bulk of the files, each side is indexed separately, meaning you only see and hear one half of the conversation. While each file has a date and timestamp to help verify when you’ve made a match, you’ll still need to find both parts separately, meaning you spend a lot of time trying to guess what’s being said on the other end through context clues.

Playback tools are similarly inconvenient. When you click a file, it begins playing just before the search term is said, often midway through. If you want to go back to the beginning, you’ll need to manually rewind the clip, keeping your mouse button held down the entire time. Even at its fastest setting, scrubbing back through the longest files can still take more than a minute. The pace is slow enough that you’re bound to notice dialogue on the way, meaning you often watch events unfold twice: first backward and then forward. You’re free to dart in and out of clips without watching everything, of course, but there’s little reason to do so unless you’re just trying to rush through.

Most notably, all of the available video clips are linked directly to the authorized surveillance targets. There is not a single file in which one or more of the relevant characters is not present. Unlike in the real world, Retina will never return a false positive.

Obviously, these limitations are necessary to provide focus to the narrative and add structure to gameplay. With a more powerful toolset, piecing together the story that unfolds across the video files—your only real objective—would be brainless. But gamifying NSA data collection like this has the consequence of rendering it comparatively toothless. This is not the terrifying all-seeing-eye Snowden described to the German media. This is the gentlest possible light in which one can depict a surveillance state. The idea of an analyst sitting in a cubicle daisy-chaining clues together and guessing what we say to each other feels quaint, almost harmless.

What makes Telling Lies such an effective commentary on surveillance, then, is that even this Playskool version of the truth becomes deeply unsettling. If the game’s limited search functionality simulates the legal and ethical guardrails of real-world spying, it makes for a chilling analogue. Those limitations are never a comfort. They’re merely an obstacle to overcome. Specific names and events you’re investigating will often be poor search terms, since they appear too frequently. Instead, it’s mundane words that often serve as the important connectors. You’re not here to view the most obviously relevant material. You’re here to find the loopholes that let you view as much as possible without technically breaking the rules.

Succeed, and your prize might be watching a child you’ve never met fall asleep to a bedtime story. You keep watching after she dozes off, listening to her breathing, lest you miss a vital bit of information. The game never judges you for this, but it’s creepy. The excitement of discovering a new aspect of the story is often chased by the disconcerting realization that no one you’re watching consented to being watched.

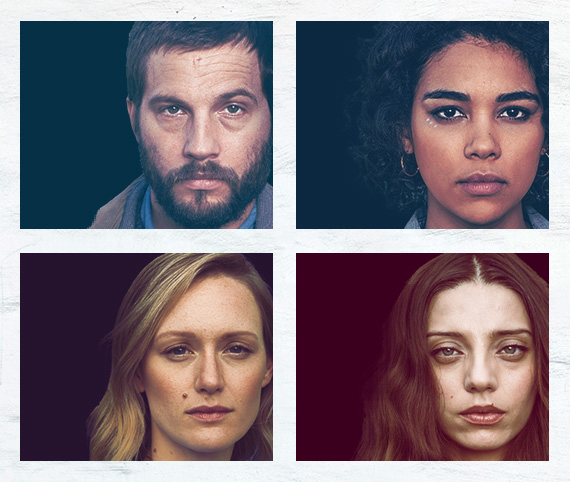

That the game can sustain this tension is a testament to the quality of the writing and performances. Like Her Story, the overarching plot isn’t particularly special, but this is a game that lives in its moments, not in its mystery. The four leads—Logan Marshall Green (Prometheus, Upgrade), Kerry Bishé (Argo, Halt and Catch Fire), Angela Sarafyan (Westworld), and Alexandra Shipp (Dark Phoenix, Shaft)—do excellent work with engaging dialogue. Sure, there’s the occasional contrived line that’s only there to serve as an obvious hint towards your next search, but on the whole it’s convincing enough, and lightyears ahead of any other FMV game you’re liable to have played.

Telling Lies does have a bit of a sex problem, though. Namely, it wants to be a game about sex while avoiding nudity in ways that strain belief. I need to be exacting with my words here, because I don’t want to imply that nipples are somehow a prerequisite for mature storytelling, or that the sexualization of women doesn’t have a particularly fraught history within gaming. My issues are twofold. First, the conceit of Telling Lies means it doesn’t have the luxury of framing or editing out nudity the way other dramas do. The camera is always a physical presence in the world, and we’re free to see everything it does for the duration of a call or recording. If there is a situation where someone would reasonably be naked in front of that camera, we’d see it. The game dodges this issue by having every sexually charged scene contort itself into a clothed, PG-13 resolution in a way that feels more and more unnatural as the examples pile up. In the aggregate, it only detracts from the necessary illusion we’re watching real people in private moments.

My second point is that nudity itself is intrinsically linked to the debates about mass surveillance upon which Telling Lies builds its premise. The contractor in a dark office watching you naked through your laptop camera is a recurring bogeyman in any discussion of digital privacy. It’s a cartoonish but effective example because it illustrates the most extreme possibilities for both parties. For the person being watched, it’s the ultimate violation of privacy. Nothing, not even our bodies, is ours to withhold from the state. For the watcher, it’s the highest transgression, reducing the complicated debates about freedom and security to simple, undeniable voyeurism. (There is a zero percent chance the genitals of you or anyone you know will ever be relevant to a national security investigation.) When Telling Lies reduces its portrayal of sex to dirty talk, innuendo, and modest lingerie, it never makes you truly confront those extremes and how they might reflect on your complicated role as player. You can feel guilty about what you’re doing, but not that guilty.

But that’s an interesting wrinkle: What’s the right amount of guilt to feel here, not just about the sex bits, but all of it? In casting you as a character other than yourself—and in constantly reinforcing that distance with the reflection of her face on the laptop screen—Telling Lies instills the sense that what you’re doing has a purpose. You’re not just you, the player, creeping in on the lives of strangers for a cheap thrill. This is a video game, and you’re a determined-looking woman, so surely whatever you’re up to is all for the greater good. And if there’s an altruistic reason behind all this, maybe you should feel just a little less uncomfortable as you fast-forward through hours of footage of someone else’s child.

But if it’s ethical, or at least forgivable, to violate the privacy of others in search of the truth and a better tomorrow, wouldn’t that also, to some degree, absolve the NSA? It’s more or less the same argument defenders of mass surveillance deploy: To stop crime and terrorism, to protect the innocent, to save the world, we should all be willing to give up a small sliver of our privacy. How much added risk are you willing to endure to know the government isn’t watching your FaceTime calls? What’s the moral calculus for converting our sexts to casualties?

Telling Lies doesn’t provide clean answers to those questions. How could it? But in exploring mass surveillance alongside the stories of its four central characters, the game does suggest a perspective: Barging in uninvited to protect someone isn’t an act of salvation, but of violence. Whether that violence can be just, and whether it is appropriate to meet violence with more of the same, remains open for debate. Trading an eye for an eye is wrong, but then again, adding more eyes isn’t working out too great, either.

Header image: Annapurna Interactive

|

★★★★☆

Telling Lies may borrow its core mechanic from Her Story, but shifting from monologues to two-sided conversations brilliantly expands the investigative gameplay, and a pivot from murder mystery to political thriller gives director Sam Barlow a much richer set of ideas to explore. A few storytelling hiccups and awkward edges do little to detract from a thought-provoking look at the modern surveillance state—delivered not through soapbox lecture but by forcing you, unsettlingly, to participate. |

Developer Sam Barlow, Furious Bee Publisher Annapurna Interactive ESRB RP Release Date 08.23.2019 |

| Telling Lies is available on PC, Mac, and iOS. Primary version played was for Mac. Product was provided by Annapurna Interactive for the benefit of this coverage. EGM reviews on a scale of one to five stars. | |