“You’ll never find this. You’ll probably never see another one of these unless you go online and look at a picture,” said Brian Marks, beaming with pride while waving around his store’s newest purchase.

Marks is the owner Game Repair, an independent game shop in Las Vegas. He just got his hands on a 56k modem for the Nintendo GameCube.

Neither he, nor any of his store’s customers, will ever actually need it. Not only do all his customers use broadband internet these days, but there were only ever three online GameCube games, and their official servers shut down in 2007.

That didn’t stop one of his employees, Nick, from immediately offering to buy the modem from him. Marks refused. It’s an obscure a piece of gaming history, and when you run a store like Game Repair, finding those treasures is one of the highlights of the job.

It’s not a job that has been easy on him. He’s still paying off the loans he took out to open another Game Repair location—a storefront that’s now been closed for over a decade.

Back in the late 2000s, there were two Game Repair shops, and there were about to be three. Marks’ business was doing well, and was even featured in an early episode of History’s Pawn Stars. He opened the doors to his third shop just before the bottom fell out on the mortgage market and took the rest of the world’s economy down with it.

He couldn’t keep the new store open. Neither could he prevent the original location on the other side of town from shutting down. By the skin of his teeth, Marks managed to hold onto a single storefront.

Credit: Phillip Moyer for EGM

In the meantime, GameStop thrived in the city, spreading to new locations and absorbing its major competitors like the chain did throughout most of the U.S. Its dominance was nearly universal: Today, there are 27 GameStops in the Las Vegas area. There are only 10 video game stores in Las Vegas that aren’t under the GameStop brand.

Game Repair is one of those 10 stores. The loans from a decade ago are almost paid off.

It might not sound like much, but few independent game stores have survived as long as Game Repair, which Marks opened in 1990 after entering into a partnership with John Balboa, who used to sell Marks used games out of his trunk behind a video rental store.

In the meantime, GameStop’s dominance is starting to show some cracks. The brand announced a plan to close about 200 stores by the end of 2019, and even more in the coming years. It’s hardly a death knell—GameStop had about 5,700 stores to its name when the announcement was made—but it’s a huge downturn for a company that’s done nothing but grow while players watched competing retailers either disappear or get sucked into its ever-growing company.

“GameStop’s doing the right thing,” Marks said of the closures. “They really should close more stores. They will.”

GameStop’s history is not straightforward. Like many corporate entities, the chain represents a lot of brands rolled into one through a series of mergers, acquisitions, and spin-offs. The company’s official timeline starts with Babbage’s, a software retailer that got its start when the founders convinced future presidential candidate Ross Perot to invest $3 million. But the GameStop brand itself, and most of its current business model, only came into existence in 2000, following a merger between Babbage’s and a different company, Funco.

Funco was the brainchild of David Pomije, a twice-failed entrepreneur whose third idea was to sell used video games via the mail. He took out ads listing game prices in the pages of a little-known monthly rag called Electronic Gaming Monthly. The scheme worked, and soon Funco opened retail locations called Funcoland, published its own game magazine, and by 1993 became the largest seller of used games in the U.S.

It’s worth noting that Funco’s stock did take a brief hit in April of that year, when Sega came up with the harebrained idea to launch a service that allowed people to download games over the internet. Investors worried that plan might be the future of gaming. The concerns were only temporary, though, and the market of the ’90s soon decided that the used games industry had nothing to fear from downloadable games.

Fast forward to 2019, when Sony announced that, for the first time ever, over half of its game sales came through downloads. Today, used games remain a significant money-maker for GameStop, but its sales in that category have fallen every year since 2011, save for a small tick upward in 2014. It’s hard to imagine that trend changing.

Courtesy Gamers Anonymous

Used games may be synonymous with GameStop, but they’re even more important to the independent stores that don’t have the benefit of thousands of locations across the country. Jon Sakura, who runs Gamers Anonymous in Albuquerque, New Mexico, said that selling new games barely even qualifies as a source of income for his store.

”We do carry new games, but it’s more of a courtesy, because of the markup,” Sakura said. “We don’t sell en masse. We don’t sell more than five to 10 copies of a brand new game if one comes through.”

Sakura told me that he ordered five copies of the PlayStation 4 remake of MediEvil from a distributor. If his store sold every single copy, he said, the total profit would be $7.

“As long as we’re not losing money, it’s something we simply offer as an extra to-do,” Sakura said. “I can’t even imagine that being a prime source of income.”

Sakura worked as a GameStop manager for two years, and he knows how efficient the company’s sales tracking and metrics are—it’s part of what allowed the chain to find success everywhere in the country. But he says that GameStop’s national policies can be limiting and prevent stores from really connecting to their local communities.

“The biggest benefit, I think, to working in Gamers Anonymous is there’s a lot of individual calls that we get to make on a personal level, on a private level,” Sakura said. “When the head corporation says, ‘Hey, we need you to do this, and market this’—they say ‘jump,’ we say ‘how high?’ But we [at Gamers Anonymous] can individualize our marketing strategy towards our specific customer base and our clientele. Being able to target people that we see on the day-to-day more specifically has helped us grow as a business.”

Tailoring yourself to your audience isn’t the only way to achieve success when running a game store, however. Sometimes, the best approach is to offer a service that you can’t find in a national chain.

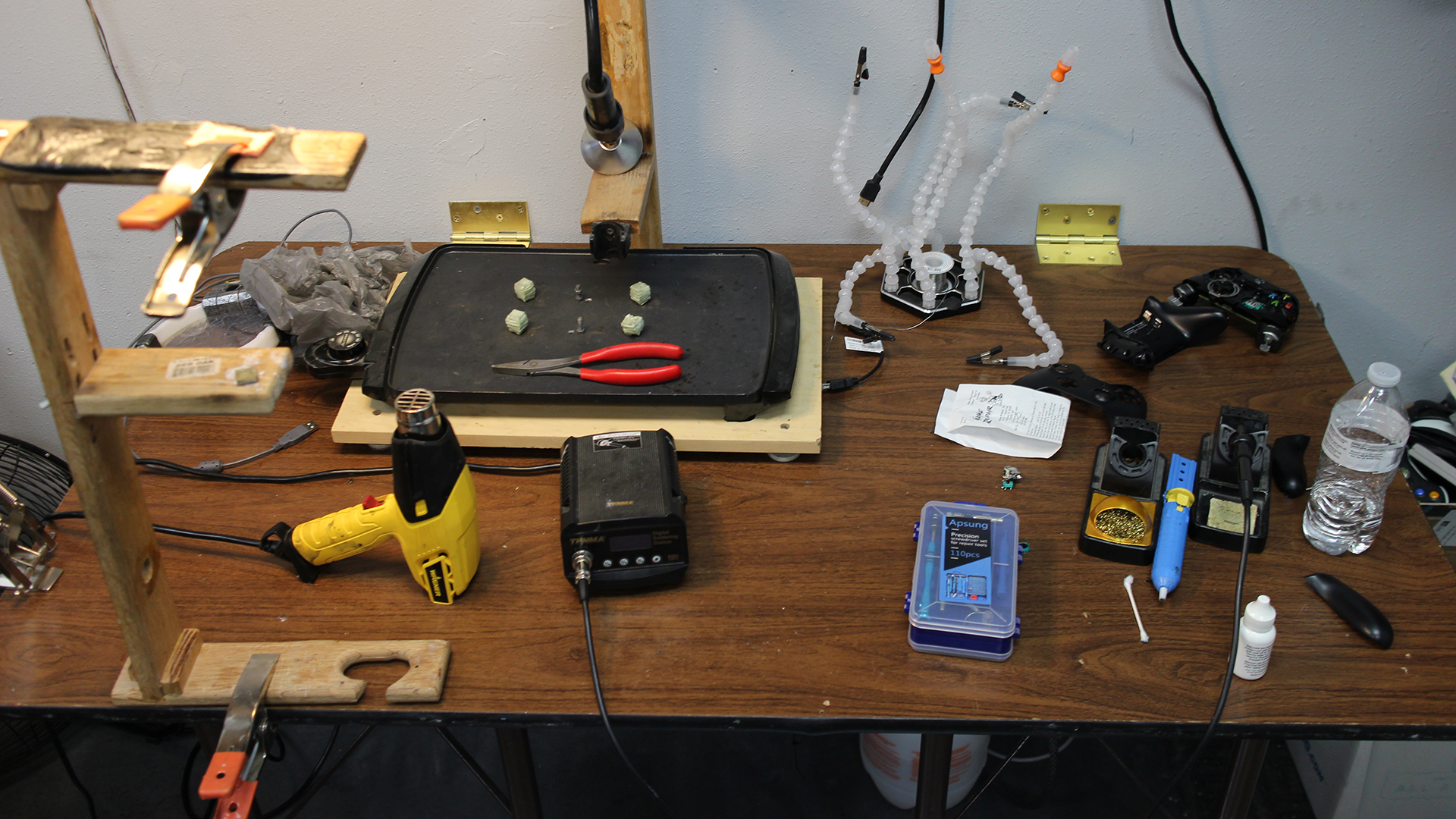

Back at Game Repair, Marks admitted that for all his love of games, selling them is not what earns his business the revenue it needs to survive. Game Repair makes 75 percent of its money off of the service advertised in the store’s name: repairing consoles.

“If I was just a video game store, I would be a waiter somewhere,” Marks said. “It’s about me doing the repairs and doing them right: being good at what I do, and being a good customer-oriented business.”

Credit: Phillip Moyer for EGM

It helps, Marks said, that he makes a point of treating customers fairly. A lot of his business comes from customers calling different repair shops and discovering that his prices are far more reasonable. He mentioned a nearby store that charges $120 to fix a PS4’s disc-reading laser.

“I do it for 79 bucks!” Marks said. “I think that’s a pretty fair price, $79 to fix something that’s $300.”

Doing more than just selling games is a common strategy for stores across the country. One notable example can be found in downtown Fargo, North Dakota. If you take an elevator to the basement of the historic Exchange Building, you’ll find Replay Games, a newcomer to the world of brick-and-mortar retail, having opened its doors in 2018.

Replay Games is a brick-and-mortar location in the most literal sense. It buys and sells used games among hanging air ducts and exposed brick walls that lost most of their paint and plaster years ago. But selling games isn’t Replay Games’ main focus, something that’s easy to see if you look around. Rows of TVs and cushioned chairs fill the room, with consoles ranging from the Atari 2600 to the PS4 and Xbox One, all ready to be played.

For $5 an hour or $15 a day, you can hang out and play any game that the store has purchased from customers. None of these titles are even put up for sale unless Replay has a second copy available, a policy that makes the store into something of a hands-on gaming museum.

“It’s just really cool to see the interest in there retro games,” said Cassidy Schnase, Replay Games’ owner. “Of course, with the book Ready Player One, playing the game Adventure is pretty novel. So we get a lot of kids that had to see how that game looked and how it played.”

The inspiration for a business like Replay Games was simple: It’s the kind of place that Schnase wished existed.

“I just got tired of waiting for somebody else to do it eventually,” Schnase said. “I really wanted a store that didn’t just focus on selling video games, like you get with GameStop and some of our local competition, I wanted a place that shared in that enjoyment of playing video games.”

That said, believing in your idea is one thing. Convincing a bank to finance your idea is entirely another. Schnase had to go to five different banks to find one willing to give him a business loan.

“The first guy actually laughed in my face about the idea, thinking it was never going to work,” Schnase recalled. “So, it’s nice to be able to say, ‘We’re here 18 months later, neener neener.’”

Courtesy Replay Games

While the business hasn’t gotten to the point where Schnase can pay himself a salary, the place has been something of a hit—it turns out that he wasn’t the only one who wanted somewhere to just hang out and play games. Replay has hosted birthday parties, end-of-year school trips, and even some corporate events.

Schnase said that the store has even helped bridge generational gaps, letting parents show their children the kind of things they used to play when growing up.

“It’s really cool to see that kind of camaraderie, especially if dads want to show kids how awesome GoldenEye was on the N64,” Schnase said. “Gameplay-wise, it’s still fun, it’s just not going to be a very pretty game. It’s fun because you’ll get some kids that are not interested in it right away, but then there’s some that will sit there and play with it for an hour.”

That’s not an entirely unfamiliar situation. Game Repair’s Brian Marks has run into a situations where kids and parents bond over the games of the past.

“There’s still a small group—it’s not as many, but there’s still a lot of little kids that see their parents playing, and they still dig it,” Marks said. “I like it that there are still kids out there that like video games. Because, you know what? Playing Zelda’s great. Playing Contra’s awesome. And kids don’t play that kind of stuff anymore.”

Courtesy Replay Games

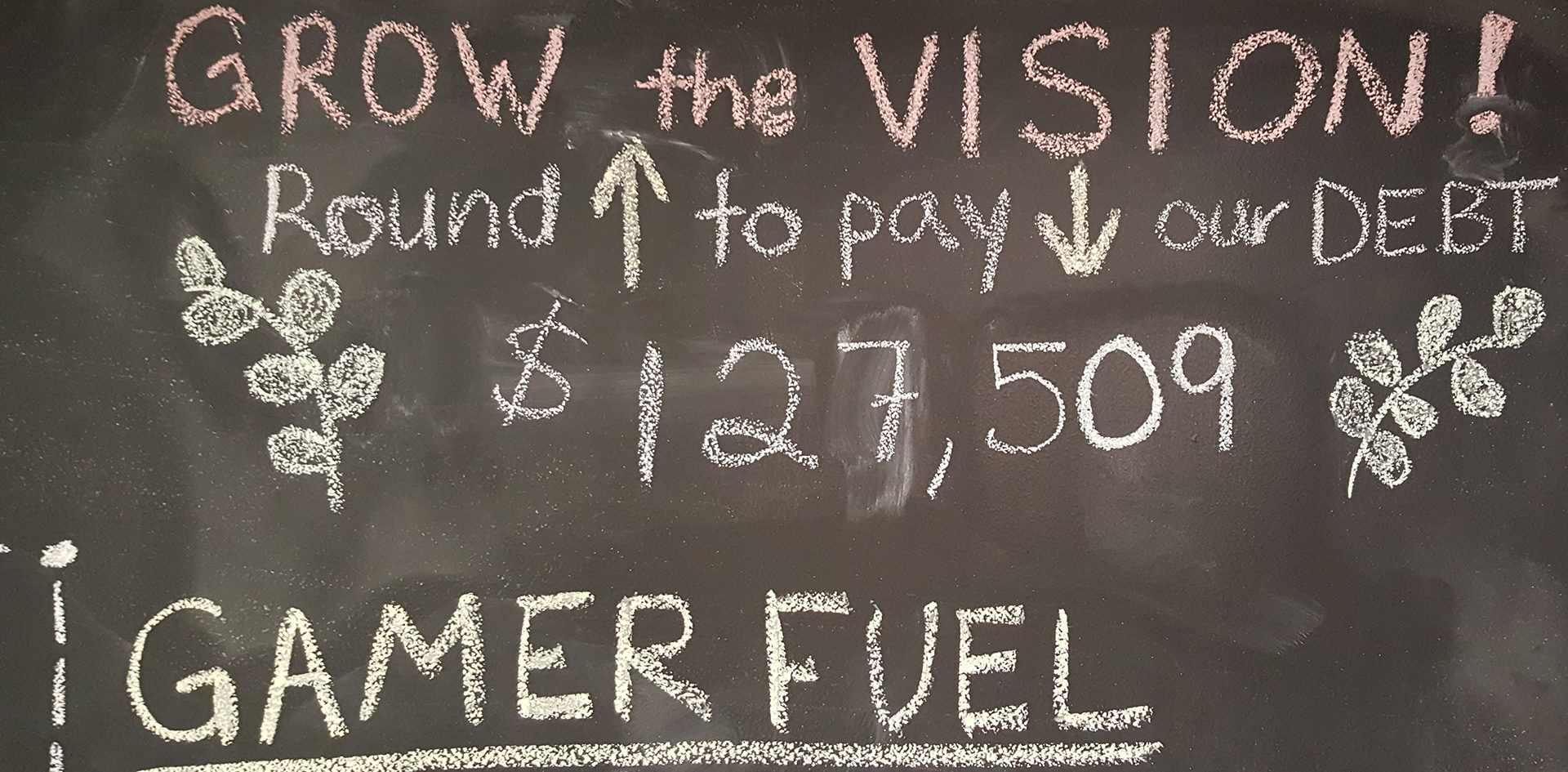

Schnase’s Replay Games thrives by emphasizing a sense of community. “It’s not just my store. It’s our store,” he said. The shop even writes the amount still owed on its business loan on a chalkboard in full view—any customer that wishes to can round up their payment to help pay down the debt.

Of course, Schnase backs up his talk with action, hosting Games Done Quick events and making donations to the gaming charity Extra Life. It’s a mindset that Schnase tries to make the core of everything Replay Games does.

“We’re a community-supported store, so if it doesn’t benefit the community, we’re not going to do it,” Schnase said. “We’re still working on letting people figure out who we are, and what is Replay Games, and what we’re trying to do. Just kind of spreading that infectious message of ‘What does a community-based store look like versus a GameStop?’”

It’s that sense of community that seems to be the backbone of many independently owned game store. The same ethos pushed Sakura to make Gamers Anonymous into a location that people with a shared love for games can come and gather. “For us, it’s not simply about trying to get sales,” he said. “Sales come when you treat people well and you have a worthwhile product. But treat the customer base with value, because they’re the ones that keep you afloat, So, let them know you have stuff that they can come do and simply enjoy.”

The store even offers a “Community Day,” which allows the more creative types among its clientele to use the store to sell whatever it is they make. “We offer them the opportunity to come down to our store and, for free, set up a table, and if they’re artists, they can sell their art. If they’re a baker, they can sell their goods,” Sakura said.

In another locally minded touch, Gamers Anonymous always houses a cat that’s up for adoption as part of a program called “Cats Around Town” run by the local humane society.

Maggie and Lucas Paynter, a married couple and part-owners of the Los Angeles–based Game Realms, also view community as a big part of what attracts their customers. They had a soft launch in March of 2016 and, at first, saw very little business. But then they made an event out of the store’s grand opening that May, bringing in Jennifer Hale, the voice actress for Mass Effect’s Commander Shepard, as a special guest.

“She helped us draw in a good crowd of customers and fans into our store for our grand opening,” Maggie said.

“It was the first time our end-of-day total wasn’t comically depressing,” Lucas added.

Maggie, who grew up in Hong Kong, lived for a while in Sydney, and finally moved stateside after marrying Lucas, has had a lifetime of love for games and plenty of experience with independent game retailers. She, along with Lucas and their third business partner, Will Delaney, had previously worked at another shop in Los Angeles before the trio opened Game Realms.

“We wanted to take our experiences and start our own store where we can share our love of gaming from retro to current games,” Maggie said.

Being in Los Angeles undoubtedly helped their success, since L.A. is something of an extreme example of how independent games stores can create a sense of community. Competitors are often on good terms with each other, and frequently send customers to other outlets to find a game they might be looking for.

“I’d rather be able to send a customer elsewhere to get what they need than send them home empty-handed,” said Lucas. “Being on good terms means those other outlets are more willing to send people our way as well.”

Like many shops across the country, most of Game Realms’ profits come from retro games from far-back eras, something that GameStop doesn’t offer unless you order online. Lucas, who says that it’d be impossible for a store to survive on new game sales, thinks that the ability to focus on retro games is an advantage that independent stores will always have over the large chains.

“There’s little incentive to [GameStop] keeping PS3 titles around when PS4 has been out for a year, but that also means they’re bailing out every time on a console market that’s in a period of downturn,” said Lucas. “In an indie store, most of the product will be clutter for a while, but not only will there still be fans, interest will return and that same market will begin to stabilize itself.”

But simply having games in stock isn’t the only thing that brings in crowds to Game Realms. Like Gamers Anonymous, the store regularly holds events—autograph signings, tournaments, and swap meet-style gatherings called “retro game swaps”—that result in a full house. That, along with support from friends and fans that Lucas describes as “a humbling experience,” has resulted in a constantly expanding customer base, one that has grown mostly from word of mouth.

Courtesy Game Realms

Game Realms might be a retail outlet, but it’s not just about getting money from customers, Delaney said. “The way we make customers feel at the store is like they’re more than just a person buying something. It’s not about the sale. You can make it about the experience the customer has at the store.”

“This way, each store gets visited,” Maggie added. “For customers who are actively hunting for classic games or rare games, they will be encouraged to check everywhere.”

Game Realms even has a game room specifically set aside for people to try out and play games without purchasing them, which has been a significant draw for some younger customers.

“We get a lot of the kids from the schools around us, and the parents over the summer will drop their kids off like a daycare,” Delaney said. “It’s funny, but this is a safe place for kids to hang out and play games with their friends.”

But even with a sense of community, the reality is that many of these stores still make most of their money the same way that GameStop does: used game sales. With a market rapidly shifting towards the sale of digital games, these stores will eventually feel some of the same pressure that’s currently upending GameStop.

Almost all of the store owners said that there will always be a value in physical games, since a digital game won’t necessarily be around forever. P.T., Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and the entire digital marketplace for the original Wii have all disappeared, and it’s hard to say how long everything else will last.

Whether that concern will keep people coming to their stores, however, is another thing.

“My worries after that would be the long-term impact on gaming culture and how such a shift would affect the economy that collectors and the like deal in,” Lucas said. “There’s been a physical component to being a gamer—especially a console gamer—that’s been eroding for years now.”

In Albuquerque, Sakura thinks that his connection to the community, along with his store’s willingness to stock games from decades past, will keep Gamers Anonymous popular even as digital distribution starts to chip away at GameStop.

“You know, what’s great about our store is, the primary focus for us isn’t simply modern-day used, but also 40 years’ worth of gaming used,” Sakura said. “I’d say we have a lot more interest in consumer affairs when it comes to us saying, ‘Hey look, we got 40 new NES games in,’ or ‘40 new Super Nintendo games in.’ People will go hand over fist trying to get to the shop to get Donkey Kongs, and Marios and Zeldas for the Super Nintendo, [N]64, stuff from that era.”

Marks, meanwhile, takes comfort in knowing that nobody will ever make an unbreakable machine. As long as there’s still gaming hardware, people will need someone to repair it—and Game Repair will be there for them.

“The hard drive crashes. The fan goes out. The HDMI gets busted,” Marks said. “People break things all the time.”

But even with their confidence, all the store owners seem to know that the secret to survival is a willingness to adapt and change, so they’re always looking for new ways to bring in customers.

At Gamers Anonymous, Sakura creates some of his own merchandise to sell alongside the games—despite all his business experience, he actually majored in graphic design, so it’s a bit of a passion project.

“We like to do a lot of fun, silly stuff. We make our own bumper stickers, posters, hats, and all of them are inspired by gaming history,” Sakura said. “We’re still sort of working through it. We’ve got an Etsy established. It’s not a primary focus for us, but I’m actually looking into the idea of maybe putting a bigger marketing push on it, because I really like doing the graphic design myself.”

Game Realms recently started offering its own repair services, something Lucas said was “long overdue.” The owners also hope to start an “Artist Alley Event,” similar to those held at anime and comic book conventions, sometime this year.

“We have to constantly reinvent our business model and ideas,” Delaney said of Game Realms. “Find ways to work with the gaming industry.”

But the need for reinvention won’t change one thing that all these stores share: the love for gaming, and the community that surrounds it.

“Interacting with my customers is probably still my favorite thing,” Marks said, sitting in Game Repair’s back room amid shelves and counters full of consoles in different states of repair. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years, and I love this job still. I can’t imagine myself not doing this.”

Header image courtesy of Gamers Anonymous.

Phillip Moyer is a Vegas-based journalist and lifetime game junkie. He grew up reading games magazines and chose his career path in hopes of one day writing for them. In addition to writing for EGM, he has been published in TheGamer and TouchArcade, and works at a local news station.