Video game release dates seem at times like a black art. We hear dates like “Q1 2021” or “October 25th” bandied around and try to guess what they mean for a game’s development. Does a delay spell trouble behind the scenes? Is there some weird logic behind a launch that goes up against a hotly anticipated competitor?

And why do games keep coming out—often just before Christmas, or around February and March—broken and unfinished, their players forced to download a massive day-one patch just to reach the start screen? Surely Ubisoft knew they’d get panned for the horrendous, game-breaking technical glitches in Assassin’s Creed Unity. Similarly, EA must have known that Anthem would be deemed over-repetitive and unfinished, and Hello Games must have anticipated that No Man’s Sky would be grilled at launch over the absence of multiple expected features.

These sorts of things have been happening for years. But why? How do games end up with release dates that they’re not ready for? How—and when—do developers and publishers decide on a given date? And how are the ever-evolving business mechanisms around games changing the way game launches work? EGM spoke with four publishing veterans to help answer these questions and to unravel the mystery surrounding release dates.

Target practice

“Essentially you’re thinking about [a release date] the entire time,” said Chris Wright, founder and managing director at Orwell and Hacknet publisher Fellow Traveller. But in the beginning of development, he added, it’s usually more of a date range—a rough target, like Q3 2019 or first half of 2022.

“You’re obviously not saying, ‘Okay, it’s going to launch on 17th of March, 2021. That’s our date,’” Wright said. “You have windows.”

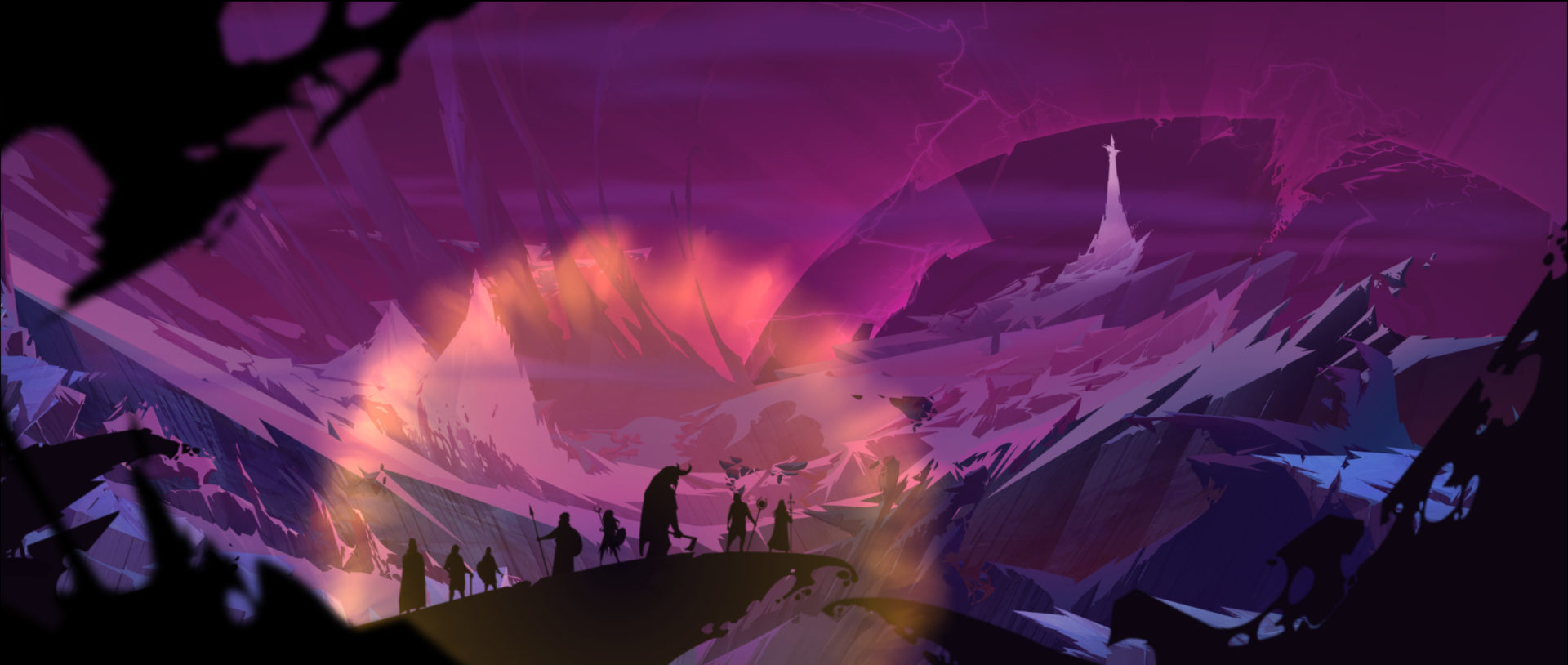

Credit: Fellow Traveler

There are two main reasons why projects start with a vague launch window. Mike Rose, founder of Descenders publisher No More Robots, explained the first of these: “Quite frankly, no game ever comes out when it’s originally planned.”

Game development is unpredictable. A level design that should have taken a week, for example, can be derailed by engine bugs and instead take three weeks. Even experienced teams often underestimate how long they’ll need to bring a concept to life or how big of an undertaking the project they’ve scoped will be.

There’s no sense in trying to be precise at the outset, then. Rather, it’s better to set a rough target to aim for—which leads us neatly into the second reason for deciding early on a launch window: money.

Video games are made with budgets. It might be an indie team’s collective savings, or a development studio’s profits, or a number based on a complicated return-on-investment calculation a publisher made. However the budget is decided, it acts as a major constraint on scheduling—a line in the sand that the developers must try not to cross. And for some companies, noted Martin Wahlund, co-founder of Warhammer: Vermintide studio Fatshark, that budget could even set a hard limit on the release date. Fail to release by then and the company goes out of business.

In any case, most games are made with a vague launch window in mind from the beginning of production. Then over time, as the development team gets further along with its work and adjusts its schedules, the publisher narrows down the launch window until they know enough to pick a date.

Credit: No More Robots

When it’s done

The mechanics of how a publisher gets to this specific date vary, however. Sometimes picking a release date is an arbitrary decision, such as when Skyrim’s original launch happened on November 11th, 2011—11/11/11—because director Todd Howard asked for it, but usually there’s a method to it.

For Fellow Traveller, it’s mainly a matter of practicality. The company works with small indie teams, and it likes to wait until they have “certainty” that they’ll hit their dates. This means waiting to lock down a date until around a month before release, when they’re to the point where the game is done and the developers are just fixing bugs and adding more polish.

This is a common approach among indies. “How often do you see ‘when it’s done’ written on a Steam page?” Rose said. “A lot of smaller developers haven’t worked out a schedule. They haven’t worked out it’s coming out in November of next year. They are praying they have it ready for next year.” This is why, Rose noted, indie games often take years longer to make than they were intended to.

This may work fine for games made by one or two or 10 people, but what about titles that have dozens or more team members and more complex schedules?

Credit: Fatshark

For Fatshark, which at more than 90 full-time staff is on the large end of the indie spectrum, Wahlund said the main priority is a game’s quality. If they don’t think a game will get a score of 80 or better on review aggregators Metacritic and OpenCritic, which they see as key to picking up strong sales and media attention, they’ll bump back their internal launch target to avoid crunch.

Wahlund concedes that many other self-funded studios lack this luxury, however, and Fatshark only able to do this because they can bank on the success they had with titles like Paradox-published War of the Roses and their self-published hits Vermintide and Vermintide 2.

Triple-A complications

Whereas even large, privately owned independent studios can focus on internal factors in deciding on release dates, the major publishers must take into account a raft of external issues—the biggest of which are physical releases and fiscal years.

“Retail sales are still, from what I understand, roughly 60 percent [for triple-A games],” explained Steve Escalante, founder and CEO of Banner Saga and Pillars of Eternity II publisher Versus Evil. So it makes sense that big games will tend to tie their release plans to the mechanisms of retail channels.

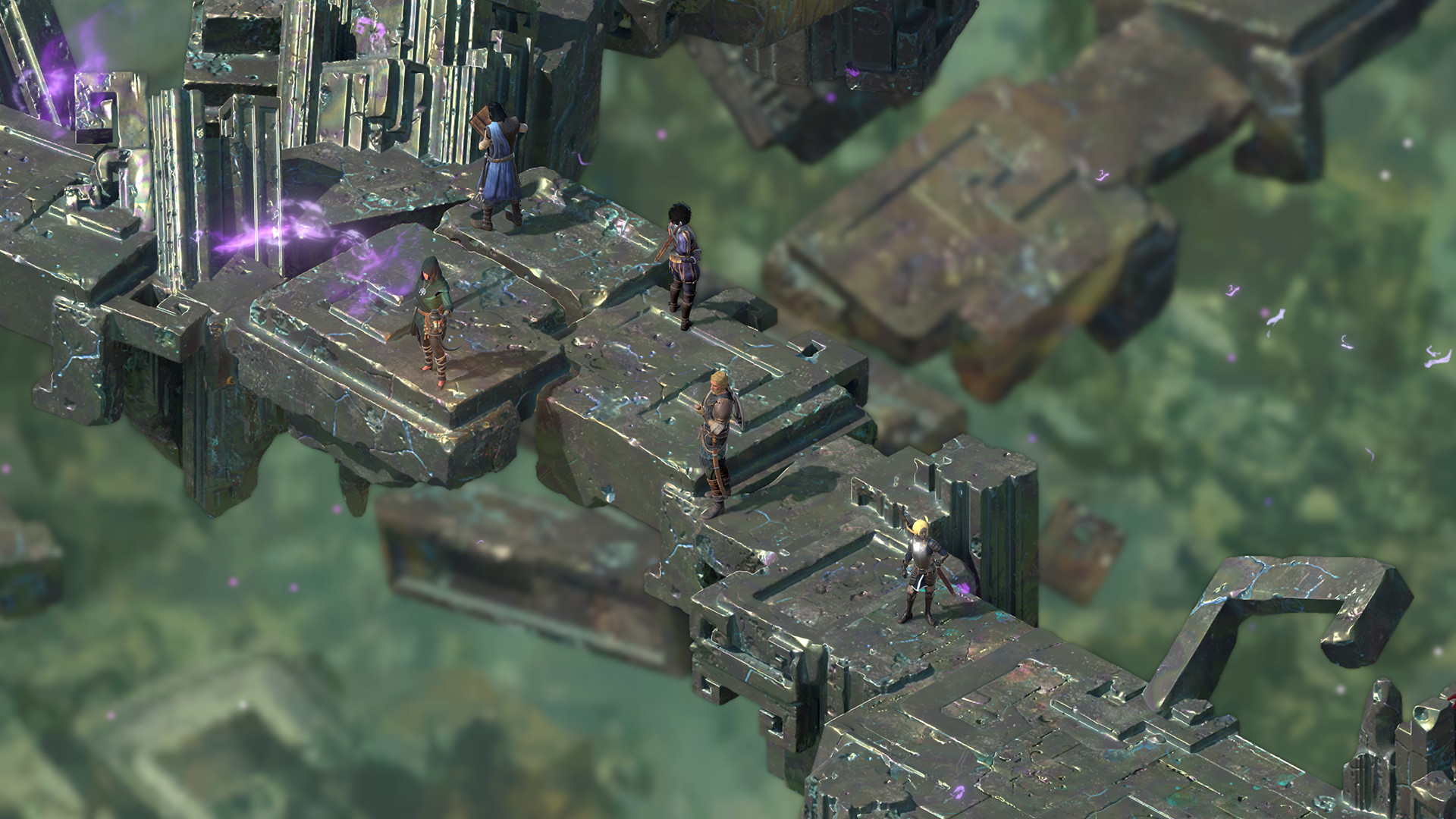

Credit: Versus Evil

This adds significant lead time to the launch process. When a game is done, it needs to go to certification, which for PC and mobile is usually a short process—perhaps a matter of days—but for consoles can easily take a month or so.

After all that, if it’s a physical game, it needs to go into manufacturing. The discs or cartridges then need to be put in their cases, which may happen in a different location to the disc replication. Then the cases go to distributors around the world, and from there they’re sent to stores, possibly via additional middlemen, where staff need to unpack the boxes and stack games on the shelves.

This process can add up to several weeks of lead time from “golden master” (the finished build) to actual release, and the cash burn on triple-A games is so huge—keep in mind we’re talking about hundreds of people working on a project—that this creates pressure to commit to a release date early, five or six months (or more) in advance, so that marketing can start building hype and sales teams can broker retail distribution agreements.

Escalante, who worked in and around triple-A before he started Versus Evil, noted that physical releases also tend to revolve around the traditional holiday shopping months of September, October, and November—when consumer retail spending peaks each year. And if hitting this holiday bonanza means releasing the game unfinished, with developers crunching to release a huge day-one patch that fixes as many outstanding issues as possible, then that’s what they’ll do.

There’s so many games that are being launched in any given month that the reality is, at a high level, it’s like there is no good release window [anymore].

Steve Escalante

But sometimes, for all their best efforts, a triple-A game just can’t hit that pre-Christmas release. And for these, a different complication comes into play. “For big publishers,” Wright said, “particularly when I was at a listed publisher [THQ], the quarterly guidance was a massive factor that had to be taken into account.”

Quarterly guidance refers to the profit and revenue estimates a publicly-listed company is legally required to make every three months. If a publisher misses its guidance—if its profits fall below the forecasted amount—then its stock price will likely go down, and that’s bad news for the board and senior staff.

“This is why you see a lot of games released in March,” Wright explained. “A lot of publishers have their financial year ending in March. If they delay that game one week from the last week of March to the first week of April, all of that revenue moves from this fiscal year to the next fiscal year. And they might miss their guidance for the year by a hundred and something million dollars based on that decision.”

Wright thinks that publishers are getting better at considering the long-term damage of a rushed release, though, both to their brand and to their staff (who burn out and leave the industry when they’re subjected to months-long crunch periods). He expects this will happen less and less often going forward—especially now that triple-A publishers each release only a few big-budget games a year, with the intention of keeping those games alive for a longer time with updates and downloadable content.

Credit: No More Robots

What about DLC release dates?

Deciding on release dates for post-launch content involves a slightly-different process to the initial launch. “With expansions or DLCs,” Wahlund said, “we’re looking more at trying to have beats so we can distribute content to the players in an even way.”

And because the game is already out, Wahlund added, there may be less of a need to worry about big titles and events—at least for something like a new season or some cosmetic items, which are mainly meant to get existing players to reengage with the game.

But Escalante notes that for certain kinds of post-launch content, like expansions, new game modes, and maybe even map packs, publishers will take care to choose a specific release date that can maximize attention from press and streamers with the hopes of attracting new players. And Rose adds that this same approach—having a major, marketable new feature in the form of a multiplayer mode—was likely the reason that Descenders exploded in popularity when it launched out of Steam and Xbox early access in May.

Credit: Fellow Traveler

Dates to avoid

Whether big budget or small, DLC or full release, picking a launch date is rarely as simple as just thinking about when a game will be done and adding a cushion for the non-development processes. “There are certain triple-As that you kind of want to stay away from because they gobble up so much of the press resources, influencer resources, and things,” Escalante said.

Mega-franchises like Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, Assassin’s Creed, and Red Dead Redemption are like kryptonite for other games—even other triple-A releases—and most publishers have learned to avoid them.

Events like E3 and Gamescom (and even PAX and Nintendo Direct streams) are generally a bad idea, too, because they generate so much news that new releases risk getting lost in the shuffle. Similarly, big sales like the Steam Summer Sale tend to pull focus from new games over to the many award-winning and well-received games that are steeply discounted.

Escalante adds that July and August are traditionally bad months for physical releases, specifically, because that’s when many people are on summer vacation and so aren’t heading into game retailers. And Wahlund notes that it can be valuable to consider events outside of video games, too, like big sporting occasions and Game of Thrones season finales. “I know people usually try to stay away from the World Cup in soccer,” he said. “You don’t want to release at the same time as the NFL Super Bowl [either].”

But even if they take tremendous care to stay away from every big thing that could pull focus away, Wahlund said, “you can always get the Apex [Legends] treatment, where something big just explodes from nowhere.”

Credit: Versus Evil/Obsidian Entertainment

Ports and localization

In an added wrinkle, games are sometimes held back not to allow more time for the developers to finish, nor to avoid competitors nor even for marketing to devise a brilliant launch campaign, but rather because their publishers want to release everywhere simultaneously.

“A game can be meaningfully releasable in a single language, on a single platform, and be four or five months away from actually launching,” Wright explained, “if you’ve got localization, other platforms, all of those things to put in.”

But if it’s done, why wait? Why not just ship in that one language on that one platform, then release the others as they’re finished? This does indeed happen for some games, but everybody consulted for this article agreed that shipping a game simultaneously across multiple platforms is preferable to launching on one system first and then the others later.

“Just simply from a marketing point of view, and a momentum point of view, it is always better to do them at once. And to have as big a splash as possible,” Wright explained.

This is as true of triple-A games as it is of indies. “If you’ve got a big marketing budget and you’re launching all the SKUs,” Escalante said, “you want them to all come out at the same time. That’s when the hype is the greatest. That’s when the awareness is the greatest. That’s when the consumer attraction is the greatest.”

Credit: Fatshark

Do release dates still matter?

All this talk about how publishers decide on release dates leaves one big question hanging: Does it even matter anymore what date a game comes out on?

Lots of games have effectively soft-launched into early access or open beta and hit their “full” launch with tens of millions of paying players in tow—examples include PUBG, Kerbal Space Program, Fortnite, and Minecraft. Most recently, EA said it will experiment with new approaches to how it releases games—the muted reception to Anthem’s confusing ***staggered launch notwithstanding.

So maybe release dates and launch windows aren’t the be-all, end-all that they once were. In an age where games can be patched almost at will, and where publishers are increasingly looking to live service online multiplayer-only game modes, titles with weak launches can end up being successful—take the slow success of Rainbow Six Siege and Destiny, for instance, and the eventual recovery of No Man’s Sky after its horrendous launch reception.

The business of games is changing in other ways, too, as publishers make more of their money from microtransactions and DLC. “As you see more and more games like Fortnite and Apex making lots of money digitally,” Wright said, “we will, I think, over the next four or five years, see some shifts in how all this stuff works and how games are released and so on. Because you start playing by the rules of digital, with physical as an extra, instead of the other way around. And that will dramatically change how this stuff works.”

For now, though, release dates do still matter—but not in the same way that they used to. Release dates going forward will be less about the black art of picking a great day and more about understanding a game’s audience, hitting a high quality bar, and concentrating all the prerelease hype a game can muster into as much launch-day attention as possible.

Credit: Private Division

For most games, a specific launch month isn’t going to spell success or failure. The conventional wisdom that January and the northern hemisphere summer months are where games go to die no longer applies. Both indie and triple-A games now release year-round, with new hits born every few weeks. And that poses a different challenge altogether.

“There’s so many games that are being launched in any given month that the reality is, at a high level, it’s like there is no good release window [anymore],” Escalante said. “We kind of laugh internally about that.”

Rose agreed. “If we’re realistic, every single day on Steam now there’s at least two or three big releases—every single day—that sell a lot of copies.”

And even consoles get notable new releases nearly every week. But on a more optimistic note, Wahlund said, “there’s so many gamers out there [now], and if there’s a niche game you do, there’s a market. Those people will buy games all months of the year. So if you just make sure the quality’s there, then hopefully the rest will be sorted.”

Richard Moss is an award-winning writer, journalist, and storyteller who explores the future—and the past—of innovation, video games, and technology. He produces the documentary-style games history podcast The Life & Times of Video Games and his first book, The Secret History of Mac Gaming, is available now. You can find him on Twitter @MossRC.