Straining your ears for the shuffling of the undead, you begin to make your way down a ruined alley. You freeze as a high-pitched crunch echoes through the grisly night. After a few seconds of silence, you slowly lift your boot from the now-shattered glass. You’ve got to be more careful. With the help of the flickering street lights, you manage to avoid stepping on any more debris. Just a few minutes ago, you had plenty of ammunition, but an unexpected run-in with a group of infected hounds left your supplies dwindling. Now, if you want to make it out of this city, every shot has to count. The gunfire on the opposite side of town has died down. You want to find that reassuring, but you get a sour feeling in the pit of your stomach instead.

That’s when you hear it. A familiar sound spills across the rancid air. The low, guttural call of a monster that will stop at nothing to make sure you die with the rest of Raccoon City.

“S.T.A.R.S.”

After the release of the widely acclaimed Resident Evil 2 remake, there’s been a lot of buzz surrounding the future of the franchise. Some players are curious to see what Capcom has planned for the next mainline title, others are more excited about the past. Many have their eyes on a remake of Resident Evil 3: Nemesis. With the recent reveal of Project Resistance, it’s clear that Capcom’s eager to keep up the series’ recent momentum. Whether or not we can expect a new Resident Evil 3 anytime soon, there’s another reason to give it our attention. Sunday, September 22nd, marks the game’s 20th anniversary. In honor of this occasion, we’d like to take a look at the game’s unique history, as well as the innovations it brought to the Resident Evil series. While many hands came together to make the game a reality, three key figures deserve special recognition for their roles in shaping what RE3 would ultimately become: Shinji Mikami, Kazuhiro Aoyama, and Yasuhisa Kawamura.

Of all the beating hearts behind the Resident Evil series, none has pumped as much blood into the series as Mikami. He directed the original Resident Evil, produced RE2, RE3, and Code: Veronica, and both wrote and directed Resident Evil 4. Needless to say, he was an enterprising force for the franchise. His work on the series began when he was asked by producer Tokuro Fujiwara to direct a PlayStation game in the spirit of Capcom’s 1989 Famicom title, Sweet Home, a horror game directed by Fujiwara himself. For his initial design, Mikami followed Sweet Home’s example, proposing what was essentially a haunted house. He envisioned a game that was light on story but heavy on atmosphere, focusing on the creation of tension and fear within an elaborate space. Although the game’s narrative was ultimately re-emphasized, the setting-oriented design remained, with the haunted house becoming none other than Resident Evil’s Spencer Mansion. Perhaps most significantly, Mikami’s focus on mounting pressure and tension led him to devise what would become a wildly successful core gameplay pattern: responding to approaching threats with limited resources. Puzzles and mysteries were used to fill in the rest of the experience, accentuating those spikes of excitement. This pattern, which emphasized survival in the face of daunting odds, led Capcom to coin the term “survival horror” as part of the Resident Evil’s promotion, cementing its status as a pioneer in the genre.

With the subsequent success of Resident Evil 2, Capcom recognized great potential in the future of the franchise, and they expanded development accordingly. Those who had worked on RE2 were soon split among a number of different teams as they began to develop multiple Resident Evil titles simultaneously. There was Resident Evil: Zero, a prequel that entered the design phase in the late ’90s, but for technical reasons would not see its development finished until its release on Gamecube in 2002, according to an interview with Tastuya Minami, the general manager of Capcom’s Studio 3. Then there was Resident Evil – Code: Veronica, slated from the outset to be a high-profile title for the Dreamcast. Finally, there was the game that was intended to be the next official main entry, Resident Evil 3, under the direction of Masaaki Yamada. Capcom had high hopes for this project considering the success of its predecessors. But there was another Resident Evil game in development during this time: a small side project known internally as Resident Evil 1.9. This spin-off title, the events of which would begin just prior to the events of RE2, would eventually become the Resident Evil 3 we know today.

The 1.9 project was placed under the direction of franchise veteran Kazuhiro Aoyama. Among the game’s primary design and development staff present during the initial phase of production, only Aoyama himself had worked on previous entries in the series, having served as an event designer and logistics coordinator for Resident Evil, after which he was an event director for the game’s director’s cut and a planner for Resident Evil 2. Although Mikami was able to provide some much-needed support, he could only do so much with so many projects running concurrently. A relatively small side project couldn’t be his top priority. It was up to Aoyama to make sure RE1.9 went smoothly.

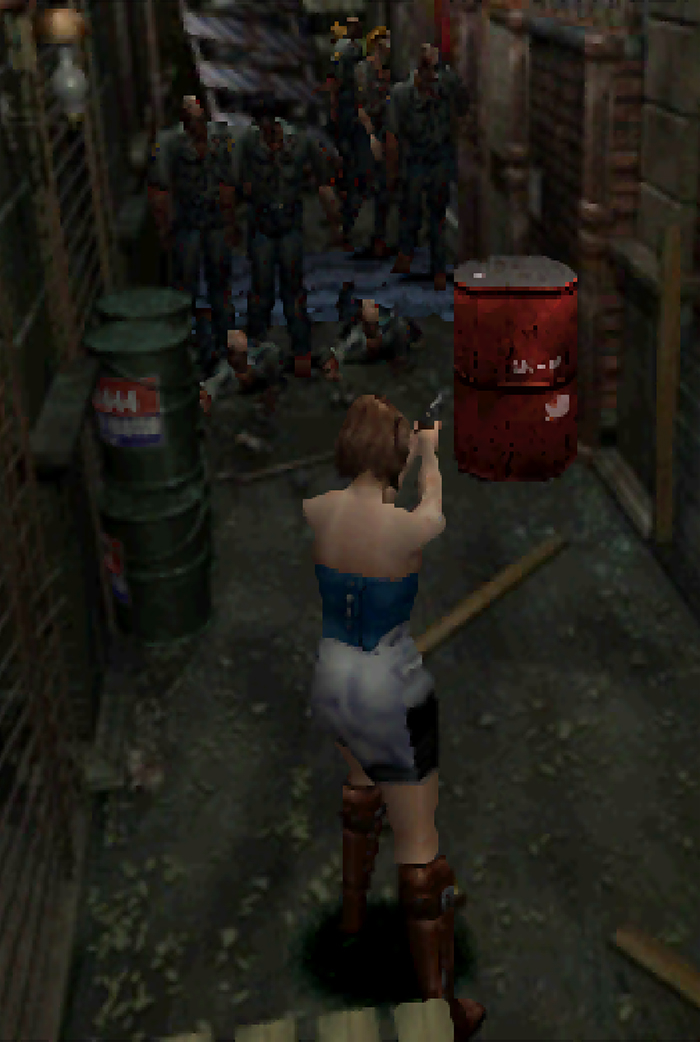

Aoyama discussed the project’s origins with Resident Evil fansite Crimson Head Elder in 2017, saying: “It was supposed to be a spin-off title, and in being a spin-off title, it was supposed to be a smaller game with a smaller budget and a smaller scale in general.” It was ultimately decided that they game would star Jill Valentine, returning from RE1, as she attempts to escape the now-overrun Raccoon City. Their goal was to make a game that would be relatively short but with high replay value, allowing them to keep the scope of the project in check while still delivering a substantial amount of content. As Aoyama put it, “You would be able to… play through this game multiple times in order to get the most enjoyment out of it. That’s why Resident Evil 3 might seem a little different to some people.”

This desire to generate replay value influenced the team’s design choices significantly. Puzzles in previous games had always been static, with set solutions that could be repeated on subsequent playthroughs. In order to vary the experience, Aoyama implemented multiple versions of each puzzle, requiring the player to engage with each puzzle on every playthrough. He told Crimson Head Elder the focus on shorter lengthy and replayability “is why this is the Resident Evil game that has all the randomized puzzle elements.… They change from playthrough to playthrough.” Similarly, this was the first Resident Evil title to include variation in enemy and item spawns, even including two weapons with swappable locations, gameplay factors that became notorious in the game’s speedrunning community.

Credit: Capcom

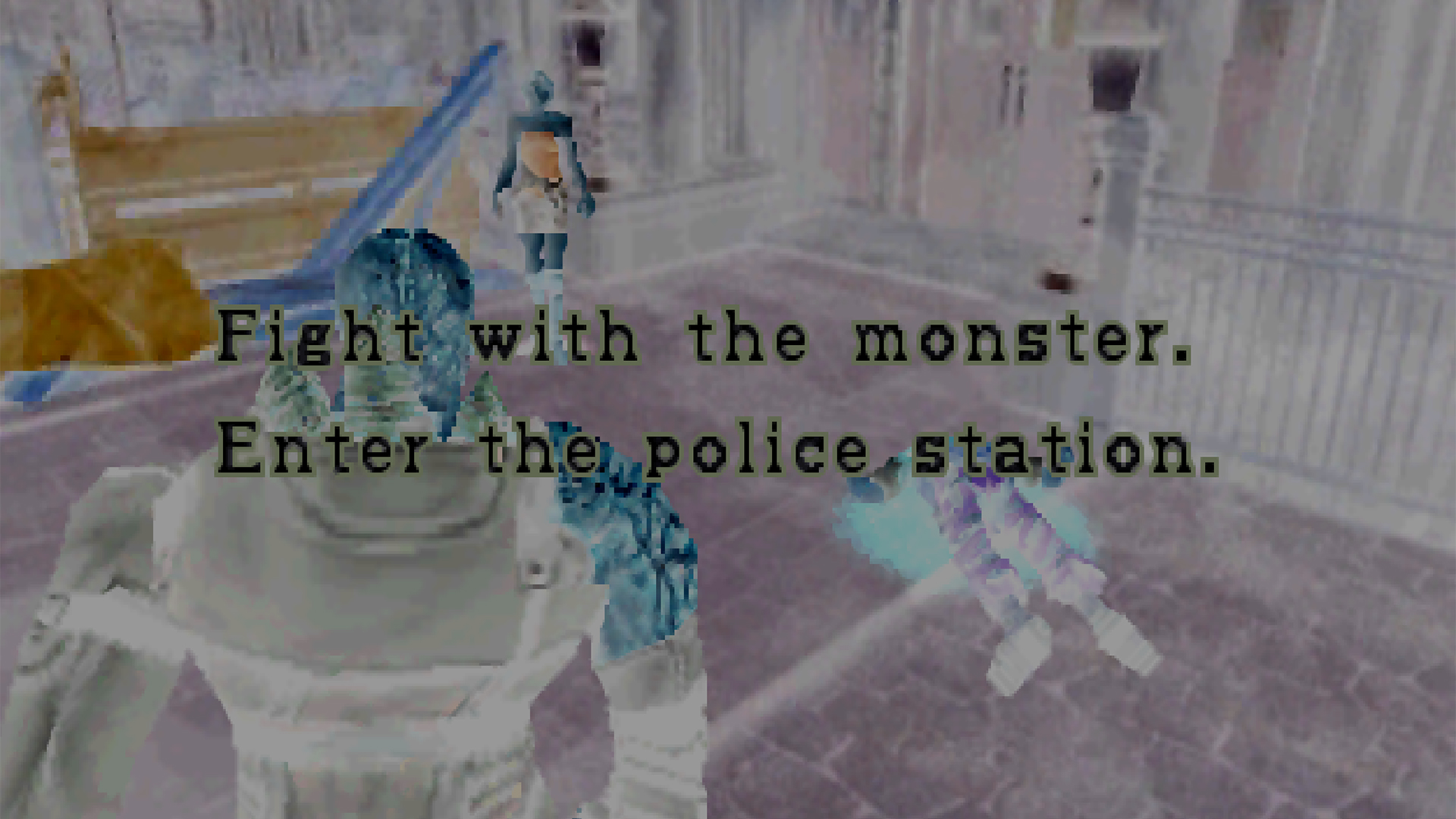

Today, it’s easy to take variations like this for granted, but this was a significant design innovation at the time. Moreover, where horror is concerned, unpredictability is a valuable part of the experience. Of all the features added in order to bolster replayability, perhaps the most overt is the game’s unique live-selection mechanic, which presents the player with branching choices at key points in the narrative. The player may be presented with a choice on whether to run or fight, where to hide, or how to handle a perilous situation. These decisions carry consequences, often related to the player’s path or equipment. Unlike the other elements, live-selections foreshadow the game’s replayability on the very first playthrough, leaving the player with tantalizing “what ifs.”

The game features a number of other innovative elements unrelated to replayability. The two most prominent of these are the ammo crafting system and the 180-degree quickturn. The former allows players to combine gunpowder types in order to generate specific forms of ammunition. The latter gives the player greater mechanical control in the face of faster, and more numerous, enemies. The player is also given access to a somewhat unwieldy dodge mechanic—difficult to master, but useful in the hands of experienced players.

but wouldn’t return until Resident Evil 7.

Credit: Capcom

Then, of course, there’s the titular Nemesis. The spiritual successor to RE2’s Tyrant (commonly referred to as “Mr. X”), Nemesis is the linchpin around which the rest of the game is built. He’s the big bad that hunts the player during their escape from Raccoon City. The emphasis on this relentless pursuer is the direct result of Mikami’s desire to make a truly frightening game, as he felt some fans were disappointed by the action-heavy tone of RE2. In 2000, Mikami told Official UK Playstation Magazine: “I wanted to introduce a new kind of fear into the game, a persistent feeling of paranoia. The Nemesis brings that on in spades. When it disappears after the first confrontation, you live in constant dread of the next attack. The idea is to make you feel like you’re being stalked.”

Nemesis proved a surefire way to boost the game’s tension. Most of the game’s live-selections are centered around encounters with this tenacious foe. In several of these moments, the player can choose between fight and flight. Players who successfully down this tough adversary in these optional fights are rewarded with some extremely helpful items. For new players, Nemesis is a deadly menace to be avoided at all cost, but opportunities to face him offer veteran players a chance for additional challenge (and sweet, sweet loot). Jill may be the protagonist, but the ever-looming Nemesis is the star of this show.

Resident Evil 1.9 was already well into its development when a series of significant changes rocked Capcom’s plans for the franchise. The first of these was the cancelling of Yamada’s Resident Evil 3. The preliminary designs just weren’t working out, and work on a new RE3 began, with Hideki Kamiya placed in charge. This change alone didn’t have much of an impact on Aoyama’s team. However, with the announcement of the Playstation 2, production supervisor Yoshiki Okamoto made the call to pivot Kamiya’s veteran team to a Playstation 2 title. This title, intended at the time to be Resident Evil 4, would undergo some drastic changes to ultimately become 2001’s Devil May Cry. The fast-paced, action-heavy style of Devil May Cry would inspire Kamiya to lead similar projects, first at Capcom’s subsidiary Clover Studios (Viewtiful Joe), then at Platinum Games (Bayoneta, Astral Chain). This change shifted the mantle of Resident Evil 3 onto 1.9, the game that had, until then, been thought of as only a spin-off. Once this shift was made, Aoyama’s team received vital reinforcements. However, the game was far enough into development that any significant changes were impossible, meaning it would have to stick to its original design trajectory.

Imagine being on that team. You’re working on your first Resident Evil project, part of a series that has garnered a sensational amount of popularity over the course of just three years. You’re excited at the opportunity, maybe even a little nervous. You walk into work one day to learn that the spin-off you’ve been working on will instead be the next mainline entry in the franchise, completing the PS1 trilogy. It must have been a harrowing experience. This is exactly what happened to Yasuhisa Kawamura, Resident Evil 3’s lead writer and scenario designer. Of all the fresh team members who suddenly found themselves working on the official Resident Evil sequel, he was faced with the most responsibility. Kawamura came onto the project in 1998 with no video game experience at all, having worked predominantly in manga and prose up to that point.

“Although at the time I had no experience in video game development, I did have experience working under Yukito Kishiro assisting in the creation of the manga series Battle Angel Alita for two and a half years,” Kawamura told Resident Evil compendium site Project Umbrella in 2012. “Eventually, I was requested by Mr. Kishiro to write a novelized version of Battle Angel Alita, which was published by Shuueisha.”

including the origins of the Raccoon City outbreak.

Credit: Capcom

Kawamura’s “experience caught [Capcom’s] eyes,” and the writer was hired to Project Studio 4, led by Mikami, to work on what was originally a spinoff title. Though excited, he was nervous about his inexperience with the franchise, as he described to Eurogamer in 2015: “I played a copy of the original Biohazard that was provided by the studio, and finished the game with the help of the complete guide, fan websites, and secondary sources available to me at the time. I needed to understand Biohazard immediately. I also had to force myself to learn how to write scenarios and documents all on my own.” When the game was made a main title, his job suddenly became a lot harder. Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2, bolstered narratively by Capcom’s subsidiary Flagship Company, had both been praised for their strong stories, with the latter including two separate, interweaving narratives. Now that his project had been thrust into the spotlight, his story would need to measure up to its acclaimed predecessors, all while progressing the overall narrative in a canonically sound way. Kawamura was able to rise to that challenge, crafting an exciting narrative that managed to make use of the game’s live-selections without adding unnecessary bulk. He also helped design the game’s bonus mode, The Mercenaries – Operation: Mad Jackal, a task he was excited for due to his fondness for Resident Evil 2’s bonus mode, The 4th Survivor (which, incidentally, Ayoma had designed).

While the project’s design remained largely the same during its transition into a main title, there were some changes, as Aoyama shared during a commentary playthrough organized by Carci and cvxfreak. In particular, many areas of the game, especially in the latter half, were expanded to varying degrees. The game also received a fully animated opening cinematic that sets the stage for both RE2 and RE3 by giving us insight into the chaos of the initial outbreak.

Resident Evil 3: Nemesis was released in Japan on September 22nd, 1999. Its North American release came soon after on November 11th, though the Europe wouldn’t get the game until the first quarter of the following year. It was an instant hit, selling over 1 million copies within a few weeks—even prior to the game’s NA or EU launches. Aoyama’s team had successfully turned what was originally a small side project into a well-received entry that remains the favorite of many fans to this day. Since then, the game has sold over 3.5 million copies. While it hasn’t reached the numbers of its predecessor (RE2 has sold nearly 5 million copies), there’s no denying Resident Evil 3 delivered a strong performance worthy of its title. Moreover, it left a lasting legacy on the Resident Evil franchise. The game’s bonus mode, The Mercenaries, became a fan favorite, returning in many future entries, including as its own full title with 2011’s Resident Evil: The Mercenaries 3D. Several of RE3’s unique game mechanics have made reappearances as well. The 180-degree quickturn has become a series staple, and ammo crafting returned, following a long absence, in both Resident Evil 7: Biohazard and the RE2 remake.

Resident Evil 3: Nemesis wouldn’t be the game we know today without the hard work of Shinji Mikami, Yasuhisa Kawamura, and Kazuhiro Aoyama. In 2010, Shinji Mikami founded Tango Gameworks, which has since put out The Evil Within and its sequel, and is currently working on Ghostwire: Tokyo. Yasuhisa Kawamura now works as an independent writer, game designer, and consultant. Kazuhiro Aoyama left Capcom in 2004 and went on to work as a programmer at Irem Software, though his Twitter profile seems to indicate that he’s left the world of game development for now. In June, he sent out a tweet that, roughly translated, reads, “No Resident Evil 3 remake at E3. A little disappointing.”

The likelihood of that remake remains unclear. In an interview with Game Watch, Yoshiaki Hirabayashi, who acted as a producer on the this year’s remake of Resident Evil 2, told fans to let Capcom know if they’re interested in a similar treatment of Resident Evil 3. It’s hard to say exactly what that means, but it seems that if fans want it badly enough, Capcom will work to make it happen. The future of Resident Evil 3 may be uncertain, but when I start a fresh file in the new RE2, and I’m running through those broad, rain-soaked streets full of the undead, I can’t help but imagine what it might feel like to escape Raccoon City all over again. When Crimson Head Elder asked Aoyama for his thoughts on a potential remake, he said he’d want to change things up a little and “keep it fresh.”He has a point. While a close remake of RE3 in the same vein as the new RE2 would certainly be an exciting gameplay experience, much of the game’s impact came from the team’s desire to make something different. In a time when risk-averse design is all too common, the unique flavor of RE3, facilitated by these differences, has become all the more endearing. Maybe the Resident Evil 3 remake we’re all waiting for is one that’s willing, once again, to be a little different.

Header image: Capcom

This article has been updated to more accurately reflect the individuals behind the commentary playthrough with Aoyama.

Nick is a writer and narrative designer living in Rochester, New York. When he’s not making games or writing about them, you can probably find him practicing martial arts. His main area of interest is horror, but he also enjoys experimental narrative, mixed media, and collaborative storytelling, and anything else that’s a little bit different. Find him @NicolasSLBrown.