Final Fantasy VII is an avatar for nostalgia in gaming. It’s one of the most frequent fixtures on lists of the greatest games of all time, and it’s arguably generated more hagiography than any of the other games it appears alongside. Square Enix has been more than happy to cash in on our collective desire to return to Midgar, rereleasing the game on PS3, Vita, PS4, PC and mobile—and now a full ground-up remake, five years in the making.

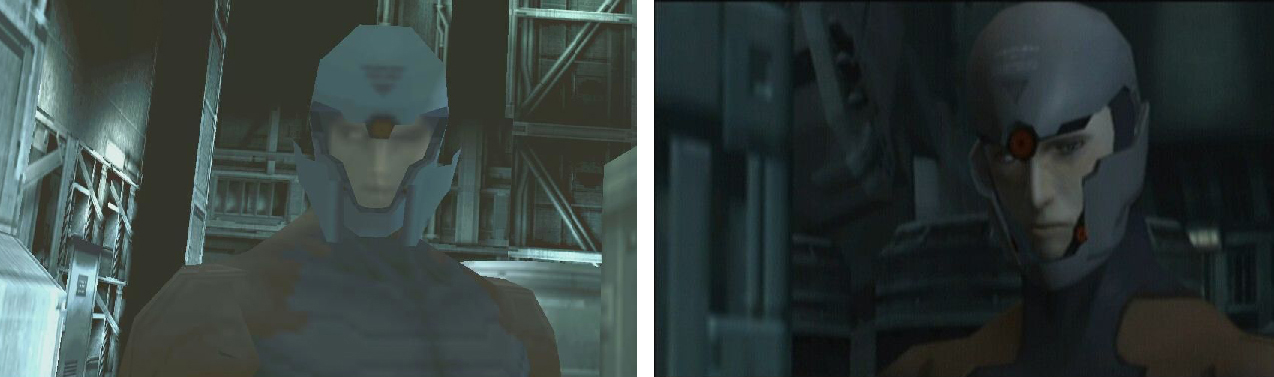

Though it is a particularly high-profile comeback, 2020’s Final Fantasy VII is anything but an aberration. It is the manifestation of a trend of rereleases, remasters, and remakes that stretches back a decade or so and shows no signs of stopping. Resident Evil, Metal Gear Solid, Shadow of the Colossus, Silent Hill, Out of This World, Oddworld, Day of the Tentacle—it would be almost impossible to list every notable game that’s been revived as a new product.

Final Fantasy VII tells us a lot about the trajectory of this trend and the ways in which the culture of nostalgia that surrounds gaming has shifted over time. In the decade that followed the original game’s release in 1997, “nostalgia” referred simply to a personal or collective experience of remembering or revisiting. In more recent years, that’s changed dramatically. Nostalgia is now a commodity. Final Fantasy VII’s rereleases, remasters, and remakes allow our past experiences to be sold back to us, offering us the promise to relive our fondest gaming memories once again.

Credit: Konami, via MobyGames users MegaMegaMan and MAT

“Nostalgia sells, we know that,” says Dr. Wijnand van Tilburg, a psychologist from the University of Essex. “Even in the marketing of food products, we know that adding a nostalgic description to food makes them sell, so it’s a known strategy.”

But why does marketing to our nostalgia work? Why do we obsess so much over games like Final Fantasy VII when there are always plenty of new games we could be spending our time with? Instead, we appear to ache to return to the games of our past so deeply that we are prepared to pay to do so again and again.

Van Tilburg explains that nostalgia as it’s understood in academia correlates strongly with popular conceptions of the term. “Cross-cultural studies show that the content of nostalgia and what people think nostalgia is, is fairly consistent. We typically use a dictionary definition to describe it,” he continues. “It’s a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past. It’s typically felt as both positive and negative, so it’s seen as a bittersweet emotion. It’s an emotion with quite an interesting history. It’s already a theme in Greek mythology: Nostalgia was a theme in Odysseus’ quest to return home to his beloved family. Later, in the early emergence of modern science, nostalgia was usually seen in psychiatry as a disease. More recently, but not any more, as something associated with depression. Before that, things like demonic possessions and other weird explanations. Within the last five decades or so there’s a bit more of a nuanced understanding of it.”

Credit: Square Enix (left image via MobyGames user MAT)

Research conducted by van Tilburg and other academics in the field have contributed to uncovering in what ways nostalgia might benefit us and, by extension, help explain why we may be drawn to experiencing it. One way in which they are doing that is by asking people to confront their own nostalgia.

“What myself and other researchers on nostalgia have done is started experimentally investigating this emotion,” van Tilburg explains. “We ask people to retrieve nostalgic memories versus ordinary memories, or we give them music that will likely remind them of pleasant times in their past. Then we investigate what impact this has on a range of psychological variables. What we find is that nostalgia can increase self-esteem, can help to overcome loneliness, can make people feel less bored, even give people a sense of meaning in life. So there are all these beneficial qualities to it and it looks like nostalgia is often used by people precisely for that reason.”

The desire to return to Final Fantasy VII, then, does not necessarily mean we are somehow stuck in the past or refusing to grow up; it may be performing an important and common psychological function—van Tilburg says it is not unusual for people to experience nostalgia several times a week. However, he points to a curious feature of nostalgia that may help to explain broader nostalgic phenomenon in gaming: the popularity of pixel art that evokes the 16-bit era, even for gamers who aren’t old enough to have experienced that era first-hand.

“This is something we haven’t studied much yet, we just know it’s possible for people to claim they are nostalgic for times they haven’t experienced,” van Tilburg says. “There is some research by my colleagues that do nostalgia studies where they find that in some Eastern European countries there’s nostalgia for their communist past, even though the people who say they are nostalgic about it haven’t experienced those events.”

Van Tilburg suggests that we can find examples of this phenomenon in gaming too, pointing to the Fallout series as an example. “The Fallout games use music by The Ink Spots that is very characteristic of the genre and this is fairly nostalgic music even though it comes from a period that many people didn’t even experience. We can even trigger nostalgic sentiments without people actually having a memory of, say, listening to The Ink Spots when they were kids.”

Understanding nostalgia’s appeal only takes us so far when considering the popularity of nostalgic gaming. It doesn’t tell us why rereleases, remasters, and remakes have become so popular in recent years. This could simply be explained by companies cottoning on to the money to be made by appealing to nostalgia over time, but there are alternative explanations worth considering.

Van Tilburg tells us that research shows that “people engage in nostalgia when there is a level of uncertainty or insecurity or they feel disconnected from others.” With that in mind, it’s hard not to notice that the trend of rereleasing and remastering games picked up in earnest around the time of the 2007-08 financial crash: Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney – Justice for All, Tomb Raider: Anniversary, Prince of Persia Classic, and PaRappa the Rapper were all released or ported in 2007; Bully: Scholarship Edition, Rez HD, and Metal Gear Solid: The Essential Collection in 2008; and the God of War Collection and The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition in 2009. Since then, the world has become a far more uncertain place, events declared “impossible”—such as the election of Trump or the U.K. leaving the EU—now our realities. Rising wealth inequality—the world’s richest 1 percent now owns twice as much as the bottom 90 percent—and the explosion of precarious work, most obviously manifest in the rise of gig-economy giants like Uber, are making people’s daily existence seem ever more unstable, while the manifestation of the climate crisis in raging blazes in the U.S. and Australia serve as terrifying signs of the uncertainty of our ecological future. As I write this article, we are in the midst of a global pandemic that’s left many of us in varying degrees of lockdown and isolation, caused tens of thousands of deaths, and wreaked havoc on the economy, leaving millions fearing for their livelihoods. Could these instabilities not help to explain why people are seeking comfort in nostalgia?

Credit: Activision

Van Tilburg is understandably cautious about making any definitive claims on this, pointing out that there are a whole range of global trends and factors which might play a part in explaining nostalgia’s popularity. However, he concedes that this may be one of them.

“One would expect that when people are in circumstances that are uncertain, for whatever reason, whether its political, social, economic, that nostalgia may help them to soothe this discomfort to some extent. It may not resolve it, but it may soothe it,” van Tilburg says. “In that sense, the popularity of nostalgic gaming fits in that narrative. In order to say that it really is that uncertainty that drives us, we’d have to test that. But theoretically, it fits.”

The idea that nostalgia might help us soothe, but not necessarily solve the problems that we are facing invites questions about the role nostalgia fulfills. Despite the many demonstrably positive effects of nostalgia, are there potentially negative ones as well?

Cultural theorists such as Fredric Jameson and Mark Fisher point to the prevalence of nostalgia in modes of cultural production, arguing that modern culture is defined by its tendency to imitate old genres and styles. You can see this phenomenon in the emergence of the genre of neo-noir, or the reference-packed postmodern style that characterizes the work of Quentin Tarantino. These works, so the argument goes, are symptomatic of a culture unable to produce anything authentically new, stuck in a loop of recycling and remixing the aesthetics of the past in a process that empties them even of the critical perspective of parody, leaving only empty pastiche. These thinkers link this phenomenon to the global triumph of late capitalism and the End of History: the idea that, in the wake of the fall of Communism and the global ideological triumph of neoliberal capitalism, society had reached its final stage, a post-ideological technocratic paradise in which only minor tweaks would be necessary and capital-H History was over. Laughable as the idea that History is over might seem in 2020, the likes of Jameson argue that neoliberalism’s decades-long hegemonic dominance has nevertheless stunted our imaginative capacity, making it difficult to conceive of a future substantially different from the present we live in. It is, as the famous saying attributed to Jameson himself goes, “easier to imagine an end to the world than it is an end of capitalism.” The prevalence of nostalgia in culture is merely an expression of this more fundamental inability to imagine a better future and take the first steps towards it.

Back in the realm of the psychological, is there a danger that nostalgia, accessed via Final Fantasy VII and its ilk, might be used as a comfort blanket to avoid dealing with not only the problems that emerge out of the contemporary capitalism criticised by Fisher and Jameson, but our personal problems too?

“Overall, it’s fair to say that generally people who retrieve nostalgic memories feel better after doing so but that doesn’t apply to everyone and the fact that people feel better may not always be the desirable response,” van Tilburg says. “It’s helpful to overcome challenges, or to feel better when feeling challenged, but of course it doesn’t necessarily solve a systemic problem. It may in some cases just be a band-aid that wears off. If you’re chronically lonely, then sure, nostalgia might make you feel better, but instead you may actually want to do something to feel more connected long term.”

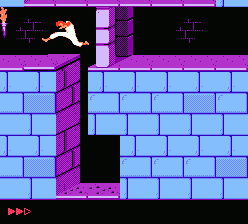

Van Tilburg argues that nostalgia holds far more potential danger when it is engaged with collectivity. “Personal nostalgia is about memories that are significant to you as a person. They may be relevant to your close family or some friends, but they’re typically not shared by others. On the other hand, you can have nostalgic events that can be actively shared with other members of particular groups.” As an example, Van Tilburg offers up Prince of Persia. Though your experience playing the game when you were young may have been personal, it is possible to share those memories with others of your age cohort who also have nostalgic feelings towards it, creating a connection.

But this same process has the potential to move from trivial to dangerous, Van Tilburg explains. “Nostalgia at a national level, people being nostalgic about glorified times in their country’s national past, that can cause conservatism and dogmatism or exclusion of outsiders. There is a little sting to this emotion that it may make one feel better about oneself, but it can also make people feel more closely connected to their in-group, potentially at the cost of other groups,” he says.

Again, Final Fantasy VII proves to be a useful lens for thinking about how this negative tendency might manifest in the world of video games. Suggestions that the Final Fantasy VII remake might rework its crossdressing scene and reduce Tifa’s breast size were met with anger from subsections of the fanbase who claim that these revisions will “ruin” the game. These complaints tended to echo an all-too-familiar narrative: women, racial minorities, LGBT individuals, and those that support them are “infiltrating” a gaming community to which they don’t belong and are forcefully changing its culture from “the way it used to be.” This nostalgia for an idealized time when gaming was, in the delusions of these abusers, free of politics—in other words, when it was targeted exclusively at young white men—is a clear example of nostalgia’s potentially toxic effect. The result has been harassment, doxing, swatting, and threats of rape and death targeting minority groups who are judged to not be “real” gamers. We might assume that the space of play would be free from the corrupting effects of the kind of distorting collective nostalgia we see in nationalist political movements, but perhaps we are mistaken.

Of course, there will be plenty of us who will not be engaging with the Final Fantasy VII remake in such a toxic way. For the majority of players, it will be a welcome opportunity to revisit a game that has a lot of positive associations and memories and enjoy the positive psychological benefits we now know nostalgia to have.

Does that mean we should be comfortable with the way in which companies have moved to own, market and sell our nostalgia back to us? Probably not. We can, however, take solace in the idea that nostalgia need never cost us anything.

“The nice thing about nostalgia is, if you use it for feeling comfortable, it’s very easy to access,” van Tilburg says. “Smells, music, sharing memories with families, looking at photographs, or simply retrieving a memory by yourself. It’s something you can do fairly easily.”

Paul Walker-Emig is a freelance writer based in Germany. He co-hosts getObject, a podcast about things in videogames, and hosts Utopian Horizons, a podcast about utopia. He can usually be found on Twitter at either @utopianhorizons or @getobjectpod.