A campfire under the stars. It’s an archetypal motif with a sort of scrappy, cosmic symmetry to it. A manmade flame mirroring and mimicking scores of tiny, impossibly distant fires. Part survival necessity, part celebration of the elements, and part diet-Promethean hubris. A dazzling semaphore signalling the heavens.

Granted, this is an especially poetic reading of what you have to assume was mostly done throughout history because, as we Brits like to say, the builder was freezing their tits off.

In games, campfires can be many things. Campfires warm weary bones, and ward off skulking shadowbeasts. Campfires boil soup and blacken meat and singe marshmallows. Campfires illuminate acoustic fretboards and thaw fingers, numb to nimble.

In their glow, the group, fragmented, becomes the circle, unified. For the lone wanderer, the campfire is where the quest—breathless, automatic, driven—becomes the journey; the companion flames allow for the silent contemplation and reflection denied elsewhere.

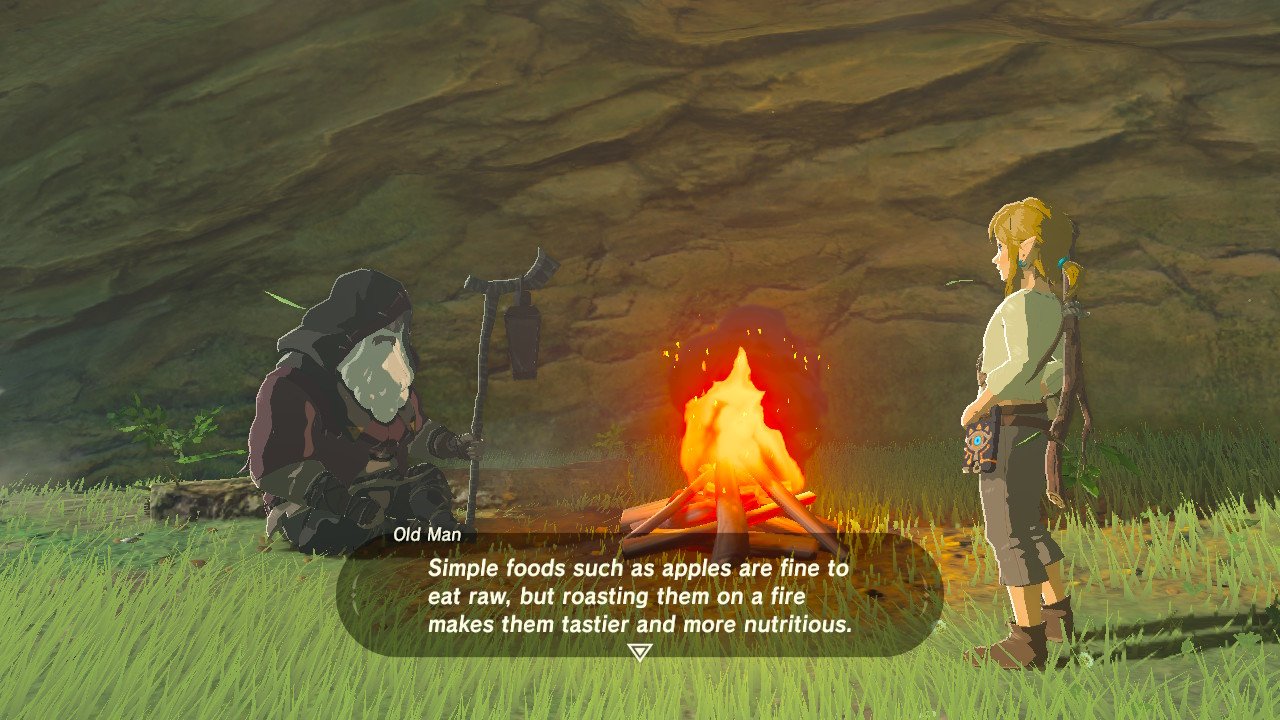

Link first emerges from slumber in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild to a calm, bright Hyrule day. It’s only natural, then, to immediately spot a mysterious hermit in a heavy hooded cloak, kicking back by the almost completely redundant light of a warm, inviting campfire. Like the other fires in BOTW, this one is pleasingly naturalistic insomuch as it conforms to expectations the player might bring with them from outside the game world by lighting torches, cooking mushrooms, and extinguishing when shot with ice arrows. But it’s also unabashedly contrived, sat in a place it doesn’t really belong, to act as an introduction to many of the games’ systems.

Credit: Nintendo

In this way, it serves as an ambassador for the rest of its fiery buds throughout gaming. As systemic functionality wrapped up in something so instantly recognizable, the campfire is beacon (sharing both a gameplay function and etymological root with “beckoning”). Something we’re drawn to without having to think about it, especially in a strange, new place.

“Fire means warmth, safety, and above all, family.”

That’s Richard Cobbett on his upcoming RPG Nighthawks, an urban fantasy story where vampires live in the open but still face prejudice, suspicion and danger. The “luckier” outcasts end up in a place called Necropolis, often gathered around a central campfire.

Cobbett said this image is “designed to invert many of the usual vampire fiction stereotypes—bohemian cheer instead of dark conspiracies, welcoming light instead of shadows, and community instead of cabals.”

“The campfire is intended as the main visual representation of that—a circle of equals who have little but give it freely, huddled together in the warmth to tell stories and strum on guitars and generally recapture part of the human experience that they may have thought forever lost.”

Credit: Square Enix

This sense of community and warmth is keenly felt in 2016’s Final Fantasy XV, where the four main characters’ long road trip towards a forever shifting horizon is punctuated by camping sequences. At these predesignated campsites, white runes spread out on the ground in a circle around a central campfire, lending the rhythm of a rubber mallet on tent pegs a ritual significance. Around the campfire, characters cook, share photographs, and spar together. This is also where the four friends level up, suggesting reflection on the day’s lessons. Near the end of the game, in an especially poignant sequence, the four find themselves around another campfire, surrounded by darkness but held together in the soft glow of the flame.

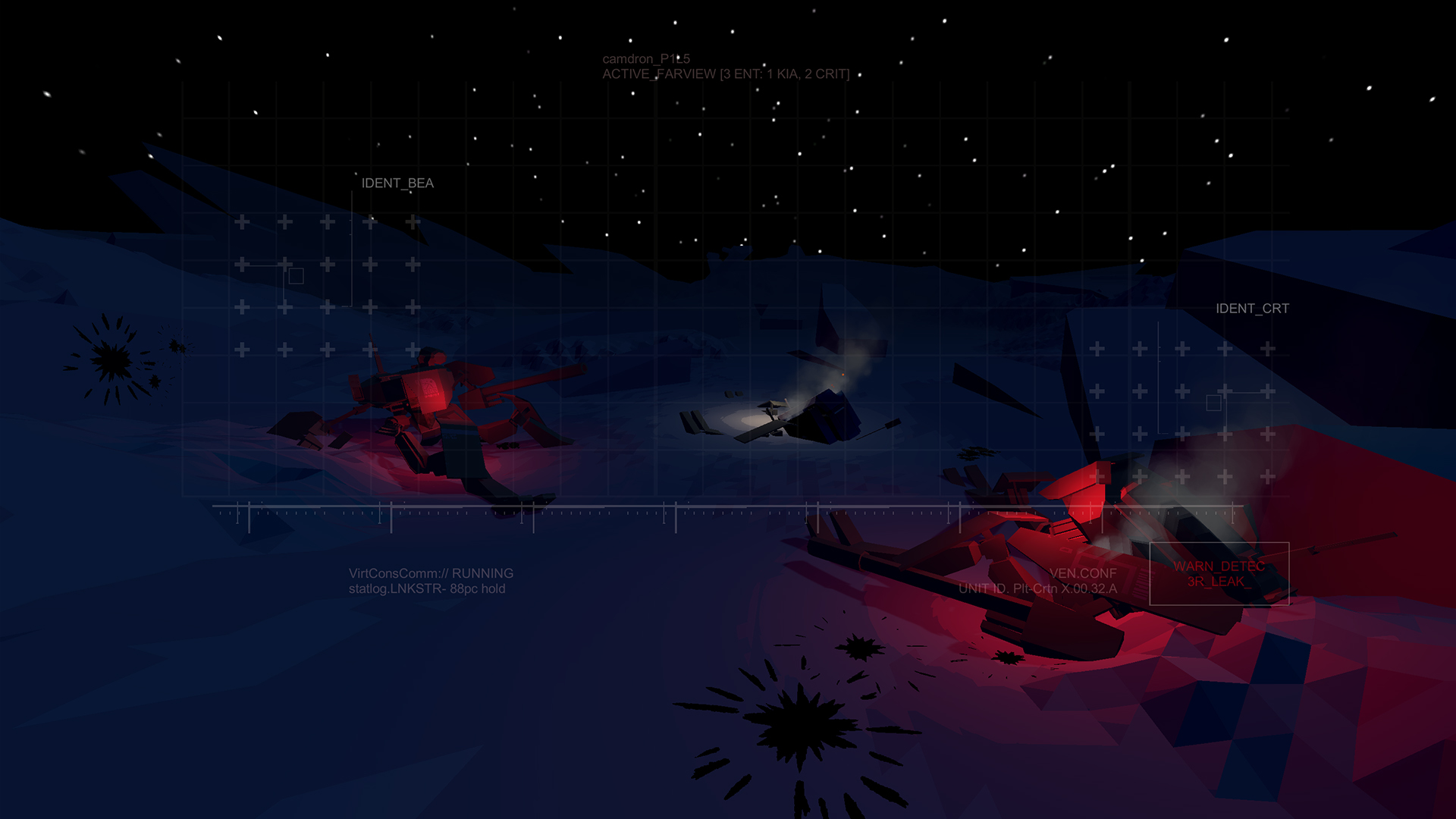

“One of the things that make campfires so ethereally beautiful is that they represent something that has to come to an end,” said Xalavier Nelson, Jr., writer and designer of the narrative adventure Can Androids Pray. “They’re inevitable in a way I don’t often see addressed in media.

“Can Androids Pray takes place during the final conversation of two angry femme mech pilots stranded on a doomed world. They’re going to die. The thing they huddle by for comfort—the flaming carcass of an enemy mech—is the same thing that killed them. This grim ‘campfire’ isn’t just an ironic prop—it directly supports the game’s theme.”

The game, Nelson said, is about “what you believe in the face of inevitability. It is a story about death. Like us, the flame will eventually die, so investing the final moments of these characters’ lives with that quiet, comforting time bomb of an image is one of the things I am most proud of in the entire game.”

Credit: Xalavier Nelson, Jr., Natalie Clayton

This same ephemeral beauty animates the flames in Dark Souls. Although referred to throughout as “bonfires,” they exist as a hybrid between the ritualistic, somber yet Saturnalian bonfire, and the weary traveler’s respite represented by a campfire. This dual function is thematically resonant with the Souls series’ larger concerns: cyclical purgatories, fatalism, inverted mythology, and the shadows that death casts over life, but also the lucid peace that waits for us when we learn to embrace loss without giving into despair. Again, the bonfires are where experience points are spent, and where enemies and threats disappear from the world, creating the sense of an in-between space, a pocket dimension sealed off from the harsh and unforgiving world outside, where one can reflect, grow, and rest.

According to Guillaume Boucher-Vidal, creative director of survival RPG Outward, setting up camp is “a moment of preparation before and a moment on relief after getting into danger.” In Outward’s harsh environments, players chop wood from trees and carry flints with them, dedicating at least some of their limited inventory to campfire building at all times.

“The campfire in Outward is a pillar of our experience because we wanted the life of an adventurer to be about more than just combat. We wanted to show that we cared as much about the mundane aspect of setting up your camp as we do about spellcasting and combat, and that is why we animated the tents and the campfire being placed. It’s also why we didn’t want it to be just a click of a button and a whole camp appeared: We wanted the player to have control over where you place your stuff and give different properties to the tents you sleep in. The distance to the fire also changes how quickly you warm up. The fire is necessary to cook and to boil your water as well. The bonus gained from being rested is strong enough that it’s something you ideally would like to do before heading into a dungeon, and since it’s how you heal from reduced maximum life and stamina, it’s also what you do once you’re out of trouble.”

Credit: Deep Silver

Much of Outward’s uniqueness as an RPG comes from how important these moments of preparation are. Its world is so demanding and dangerous that the feeling of elation and safety in these quieter moments is amplified.

“We also wanted the night to be really dark as an extra reason why the player would want to sleep,” said Boucher-Vidal. “Every encounter in our game can turn sour, so seeing where you’re going and where are your enemies are key to your safety. It makes the light of the campfire that much more inviting.”

This survival is the primary focus of The Long Dark, a game its creative director, Raphael van Lierop, describes as “about the hundreds of small ways you strive to extend your life in a world that is hostile to your existence.”

“In general, the best way to protect yourself from cold and wildlife is to seek shelter inside the protection of a roof and four thin wooden walls. But with over 50 square kilometres of wilderness to explore, and human-made shelters often few and far between, it’s inevitable that you’ll, at some point, find yourself at the mercy of a campfire.

“When desperate to beat back the darkness of a cold winter night, the campfire casts a gentle protective glow around you, provides a light source, a point which to navigate back to if you ever have to venture out looking for more fuel, and the means to protect yourself—or light your way.”

Credit: Hinterland Studio Inc.

In The Long Dark, players can use fire to melt snow, cook food, prepare medicine, and deter wildlife.

“Besides the gameplay benefits, campfires offer intangible psychological benefits to the player,” van Lierop explained. “They provide you with the tools you need to protect and preserve your life, allowing you to take ownership of your own survival. And the pleasant sound of crackling branches burning in the winter night can lend a sense of psychological safety in a world whose comforts can often feel mean and maddeningly infrequent. The campfire is comfort and safety, and is often the difference between life and a very cold death.”

If the campfire’s place in our shared histories facilitated and nurtured the way we tell stories—as anthropologist Polly W. Wiessner argues—then it also makes sense that campfires would hold so much significance within these stories, a sort of a semi-mythical motif in our shared history of storytelling, and a conduit between fictional worlds and our own. No matter how far we’ve wondered from our humble village or crashed plane or prison cell, we recognise campfires along the path because the campfire is—at some point in our shared history—the place where the story began.

Header image credited to Bandai Namco

Nic Reuben likes to pause games every five minutes to ponder the thematic implications of explosive barrel placement. You can follow his infallible wisdom @nicthehumanboy.