Warning: This piece contains spoilers for the ending of Outer Wilds.

I am 25 years old and struggling to come to terms with my own mortality. It would seem that a quarter (or more) of my life has passed me by. Often I stop to think: What have I accomplished with this life I’ve been given? Have I used it properly? The planet is dying; could I have made better lifestyle choices to make a difference? When I become bogged down by these anxieties I often find it helps to take a step back and cede control to the greater forces of life and just let it flow, since at the end of the day I’m merely one of the more than 7 billion people alive today. I can only do so much.

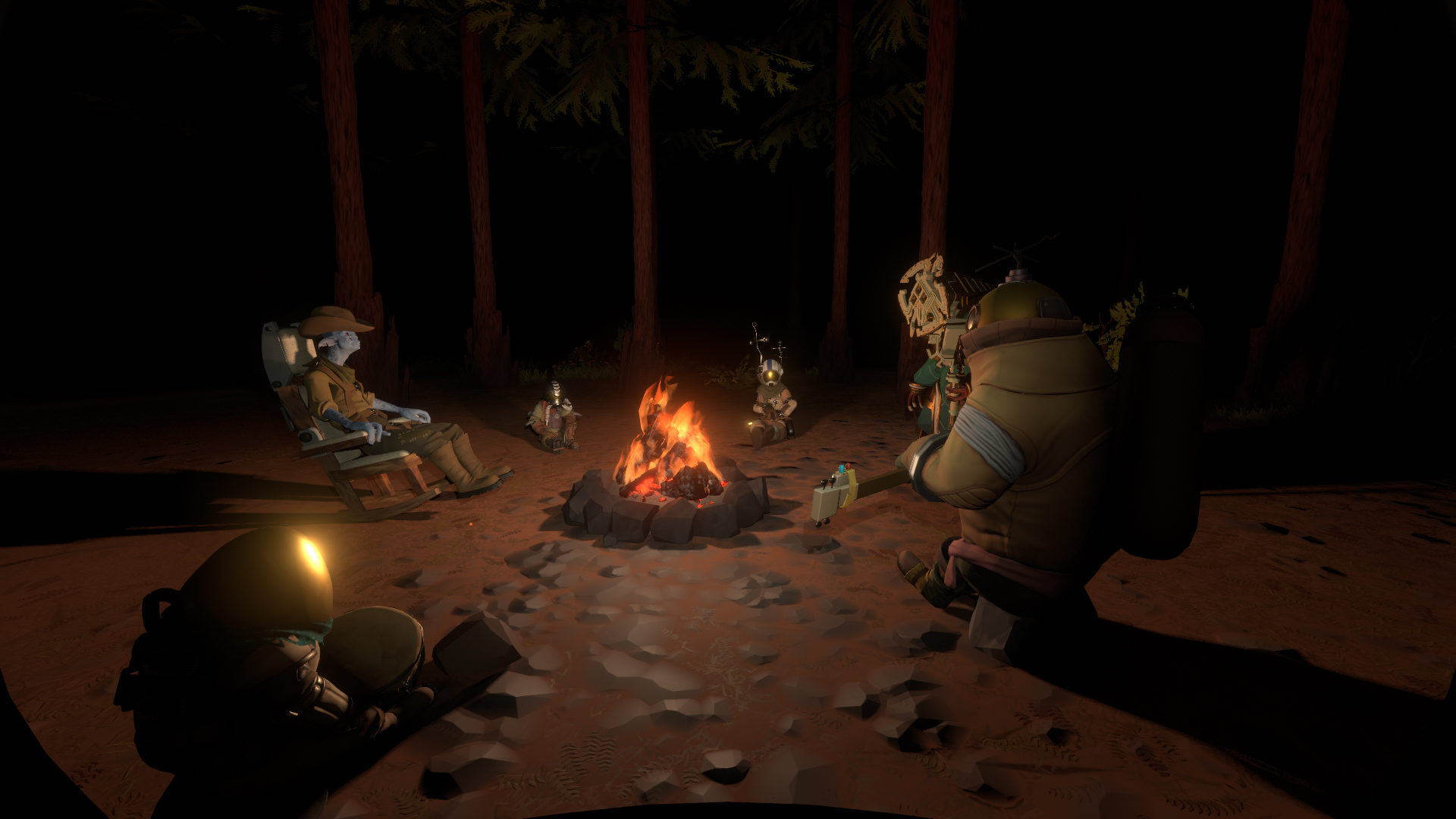

Mobius Digital, the developers of last year’s critical darling Outer Wilds, seem to share these fears. The game opens with an abrasive intake of oxygen, as your bleary-eyed and unnamed protagonist awakes in a sleeping bag by the smoldering ashes of a campfire, staring upward at a wondrous collection of stars mottling a great expanse of morning space. Outer Wilds immediately clues the player into the possibility that the very fabric of reality may be upending itself as you watch a faraway space station launch an object and simultaneously splinter into pieces before your very eyes. In any other game, such a cataclysmic event would be grounds for concern and prompt action, yet the first thing many players will likely find themselves doing is to talk to a nearby camper named Slate about an imminent first launch into orbit, followed by roasting a few marshmallows spiked on a severed tree limb.

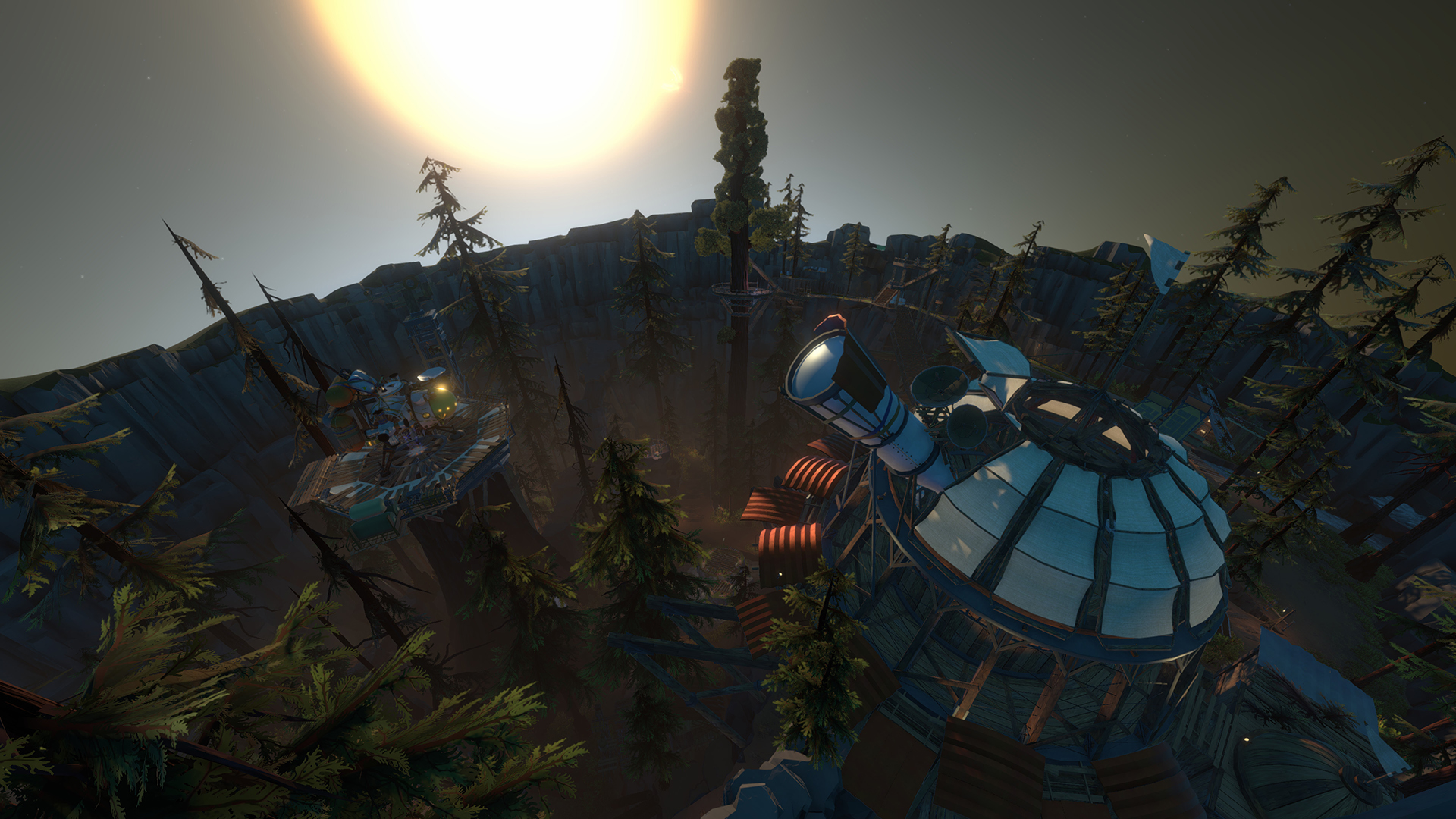

You are a nameless Hearthian, a four-eyed native of the planet Timber Hearth. It’s a lush, bucolic world brimming with green grass and verdant trees, their boughs swaying to and fro in the breeze. A deep blue sky quells the haunting darkness, and angelic acoustic guitar strings herald the morning’s arrival. This cosmic vista’s brilliance draws your eye upward to watch the planets as they orbit a sun much like our own. Here is a landscape fit for cabin homes and causeways fitted into the land with wooden decking boards, a place where children ask you to play hide and seek with them and an observatory tells tales of a legendary tribe of goat-headed people called the Nomai who traveled from a far-off galaxy and made their mark in your solar system. This observatory doubles as a museum. Inside, crystals affix themselves to the wall with their own gravitational pull, strange markings can be decoded to reveal messages, creepy anglerfish swim in tanks, and a quantum rock darts around a side area when not looked at.

It’s a cozy village home, yet as the intrepid adventurer, your immediate goal is to receive the launch codes to your spacecraft from the observatory keeper Hornfels so you can leave. After all, that thing up there just blew up. Why not go and find out what caused the explosion? There’s no time to waste, so you point your directional signalscope upward, which lets you dial into the frequencies of others like yourself who have made landfall on distant planets.

Before you exit the observatory, a statue of a Nomai head seems to animate, turning toward you and… are these pictures of things I’ve just seen? Strange, but you ignore it. With the launch codes in tow, you lift off for the great beyond. Navigating the idiosyncrasies of your propulsion system takes some getting used to; the ship has an unexpected corporeality. Orient your viewport back toward Timber Hearth and you’ll notice that other parts of the planet lack the fecundity of your home village—more gravel and dirt than flora and fauna—yet you might also notice hints of other things to see there. You realize that you are small here, not the inevitable center of the world as in many other games but one specimen in a greater ecosystem of reality.

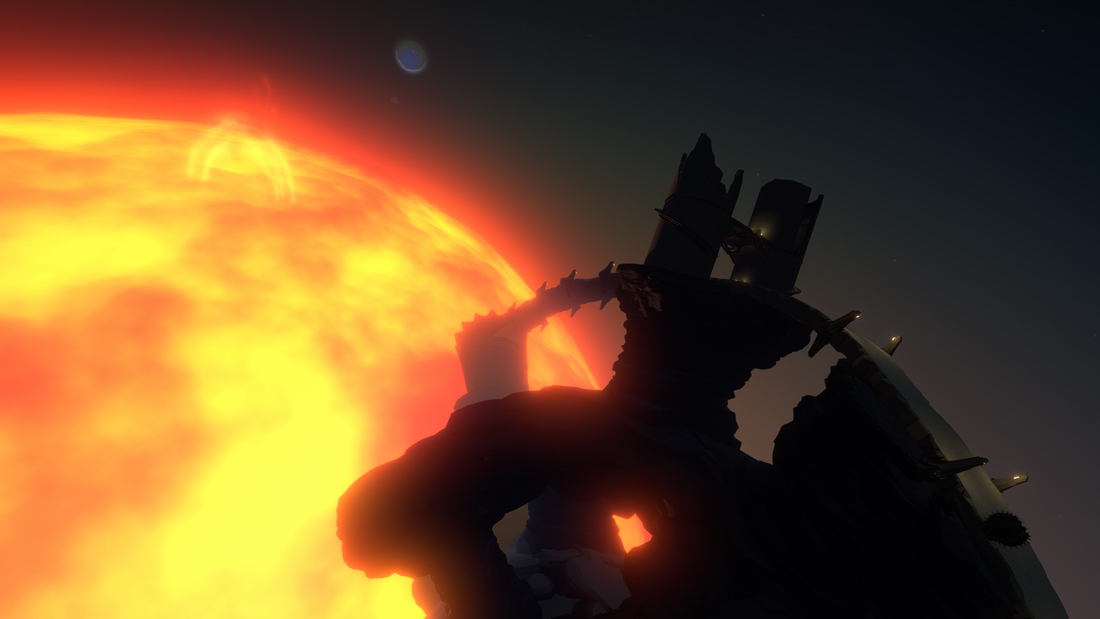

And in ecosystems of all sorts, there is always death. As you play Outer Wilds, you will inevitably die likely hundreds of times and respawn back at that same campfire you started out alongside. Outer Wilds is a game about loops, cycles. Each loop starts precisely how I’ve described here, at that same campfire on that same patch of land upon Timber Hearth. Each loop lasts 22 minutes, at which point the sun goes supernova and swallows up everything, yourself included, assuming you haven’t already died along the way. The game uses this central gameplay conceit to expand out and explore the cycles which govern all life, from the ecological to the personal, and particularly how these cycles are inexorably intertwined.

Outer Wilds reminds through abstractions of phenomena both earthly and cosmological what it means to be small and vulnerable to the inevitabilities of life. It is at points a cold, grueling, boring experience—just as life is. You can make one small misstep and end up having to redo much of your loop from scratch if you find yourself careening toward a precarious death. Its endgame requires the player to wait several minutes for a particular building to be accessible, and then to walk through a doorway at one exact moment, grab a certain object, and fly all the way across the solar system to a planet named Dark Bramble to access the hidden ship graveyard of Nomai long forgotten.

Once you have this object in hand and embark on your final flight, a remix of the end of loop music plays to cement in the player’s mind that this is truly the end of the line. As I made my way to my destination, I reflected on my time with Outer Wilds. I hoped against hope that in the end I would be able to save the fellow Hearthian explorers I’d met along the way: Chert with his cheery percussion, Esker with that whistle, Riebeck plucking the banjo, Gabbro on woodwind flute, and Feldspar on harmonica.

Mostly, I thought about the good feelings. In arriving back at the dreaded Dark Bramble, I realized in my wistful reflecting that I’d forgotten how treacherous Outer Wilds can feel. Even when you’ve done it numerous times, navigating through Dark Bramble’s impossible voids never ceases to feel tense, as loud noises will attract the attention of enormous, horrifying (read: horrifying) anglerfish whose teeth are enough to deter me from fully replaying the game. In setting the penultimate stretch of the game back in Dark Bramble, the game wants one more time to remind you of this fact: The world can be a dangerous place. All of life should not be for us to conquer or explore.

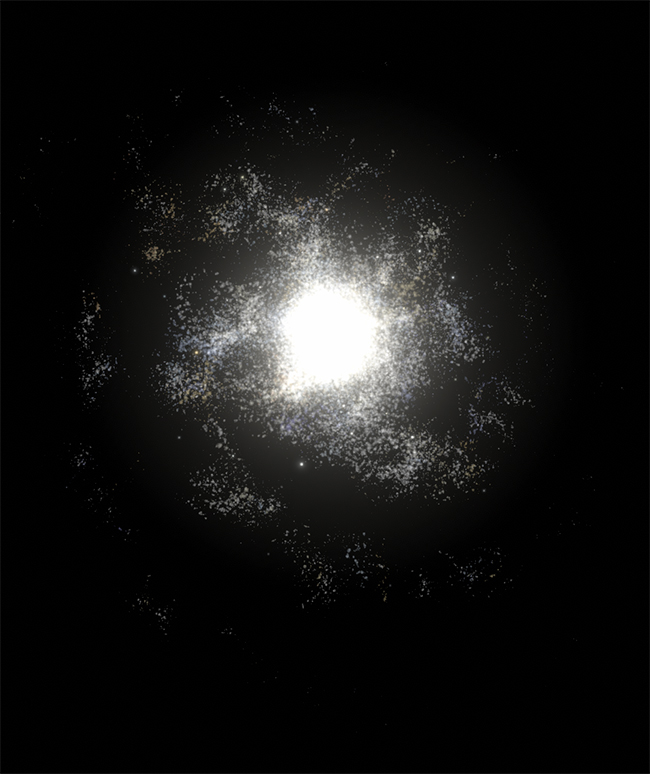

I’d only partially get my wish for a tranquil reunion with my compatriots. After teleporting to the fabled eye of the universe using a warp drive and a password aboard the ship on Dark Bramble, you fall through a quantum tunnel and, long story short, end up in a dark forest situated between worlds, both somewhere and nowhere, a quantum being of your own. You’re given the privilege of gathering up your friends around a campfire in this liminal space to join forces and perform a gut-wrenchingly beautiful group rendition of the game’s main theme. Their combined playing conjures up a ball of energy hovering above the campfire, which when entered allows the player to watch the creation of a new universe before their very eyes. Post-credits—assuming you met Solanum, the last living Nomai—13.8 billion years pass and new life begins to appear within that new universe. All the while, the Outer Wilds Ventures crew continues its campfire reverie for eternity.

Outer Wilds ends with sadness. Everyone you meet dies. You didn’t save anybody. You’re definitely not the hero in anyone’s story. Like the subatomic particles which comprise everything in the universe, you were just an erratic and violently gestating microentity in a macrocosmos of others just like it. Deep down, you probably knew it would turn out like this. There is grief in this reality, but also the comforting thought that endings yield new beginnings. Life.

I’m lucky. I’m fairly young, and I’ve yet to suffer the deaths of any family members or close friends. This is to say that largely my experiences with death have been more abstract, with me being the type to endlessly ruminate over more secular anxieties about what happens after life. While I have known some people who have passed and have lost a few pets, none of these felt like earth-shattering losses, the sort where nothing but an impossibly large vacuum gets left behind.

As 2019 approached its conclusion and I scoured the solar system of Outer Wilds every waking hour that I could, I learned that a coworker of mine, someone I’ve known for over five years, is suffering from an illness which may soon cut her life short. She left a letter in our break room thanking everybody for the friendships she’s made during her time at work. Even though she and I are not exactly close, this is still a person with whom I’ve spent a good amount of time in the same circles. Reading her brief letter of farewell made me think more deeply about the finality of death.

Similar thoughts must have weighed heavily on the folks at Mobius Digital during development. Before you end the game, you can talk to the banjo-playing Riebeck, who says, “The past is past, now, but that’s… you know, that’s okay! It’s never really gone completely. The future is always built on the past, even if we won’t get to see it.”

Crucially, Outer Wilds, in its conclusion, centers around the people you’ve met and the relationships you’ve made along the way, rather than its quantum physics or phenomenology. Above all, the story it tells is one fascinated with time and its effects on the environment and our bodies, our personhood. With the passage of time comes sadness, the game reminds us, but sadness can only exist if happiness and hope do too. That’s something you have no control over, something you can never change. You just have to let it be and make as positive a mark as you can with what you’ve got.

Such is the terrible, beautiful way of things.

All images: Annapurna Interactive, Mobius Digital

Devin Raposo is an unemployed software engineer, writer, 3D artist, musician & game developer based in Florida.