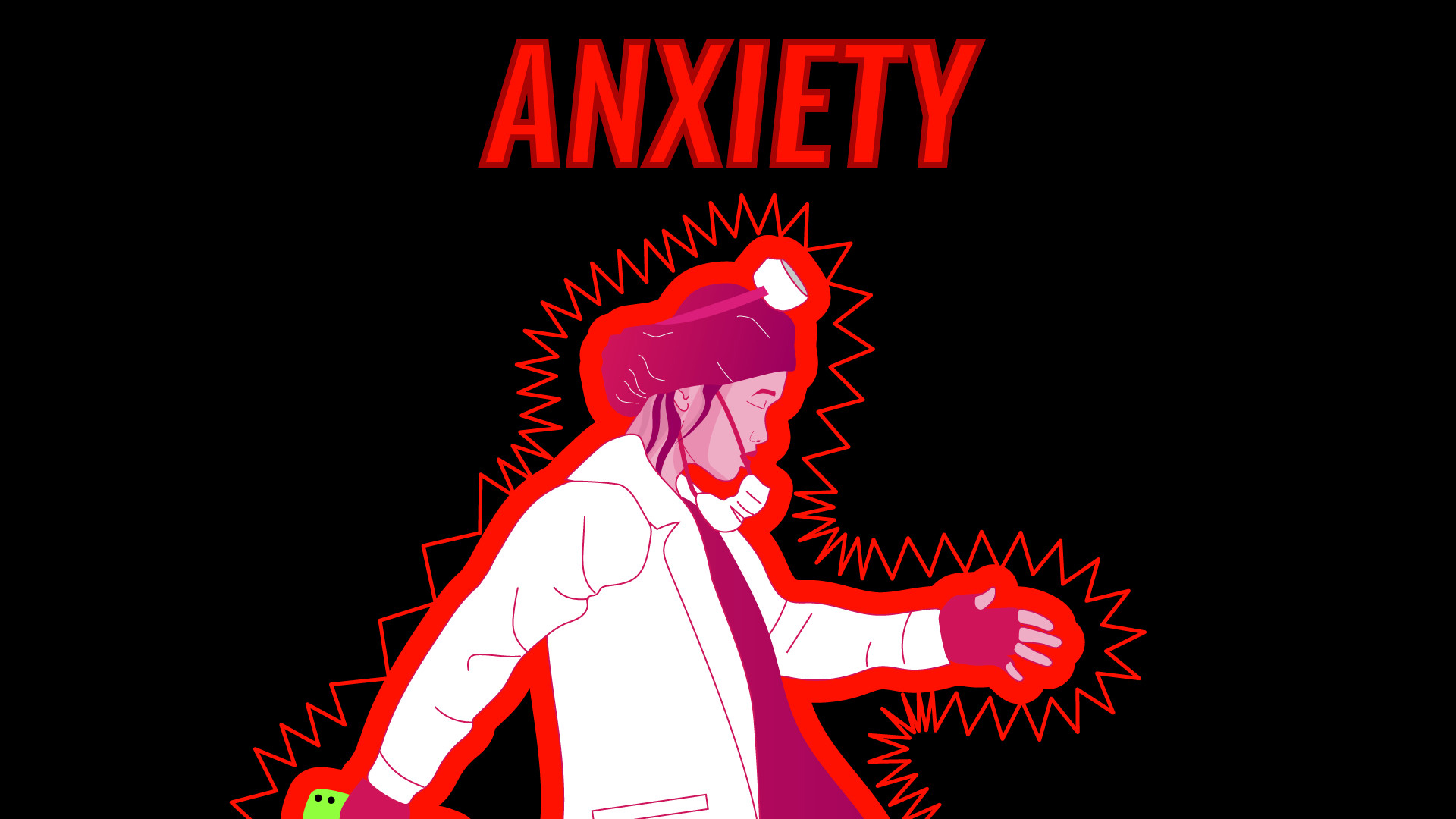

The first time I ever spoke to Jan Cieślar, he was tucked away in the chaos of the Game Developers Conference, on a delicate cell phone connection, desperately fielding every inquiry he could for Invisible Fist—Failcore Games’ flagship title, and one of the few plainly anti-capitalist products on the show floor. The gameplay brings to mind Slay The Spire, Cultist Simulator, and the rest of the experimental card-battlers that have made appearances on Steam’s trending page. But as soon as you settle into the narrative, you’ll see exactly what Cieślar is angry about.

Invisible Fist has three difficulty thresholds. On easy, you play as a gadfly billionaire tech baron—say, a Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk type—who’s eager to get their next data-reaping startup off the ground and into peoples’ phones. On medium, you’re a broke college student holding on to the scant hope of someday being a homeowner. On hard, you’re a factory worker across the sea, toiling away in a putrid smartphone sweatshop, with dreams of someday becoming a pop star. In each mode you’re equipped with a starting deck of cards, and engaged in a mortal struggle against the personification of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. You fight by playing cards that manage three primary resources—sleep, work, and recreation—which, in turn, represent the way all of us try to divy up the hours between staying sane and fighting for our dreams. You win by beating down the literal free market, or you die trying.

Of course, in Invisible Fist’s sardonic twist, the billionaire tech baron’s deck is a hell of a lot better than what the college student or the factory worker are dealing from. For instance, when our Zuckerberg stand-in wants to relax, they might play a card that reads “20 Course Meal.” It goes without saying that the college student doesn’t have that card. In our current economic logjam, it can feel like the deck is stacked against you. Invisible Fist takes that feeling and makes it literal.

Credit: Failcore

So it was ironic to consider Cieślar’s predicament. Here he was, promoting a game with a brazen political creed, while trapped in the rat race of modern video game development. He needed journalists to write about Invisible Fist to fund its Kickstarter, he needed to fund its Kickstarter so he could continue to make games, he needed to make games in order to find his zen. One of the central knife-twisting paradoxes of Invisible Fist is how much work it takes for an average person to witness even the mildest improvements in their outlook. Cieślar thoroughly comprehends his plight, but that doesn’t mean he’s not stuck within it.

“We’ve had some naysayers. ‘Socialists asking for money, how typical!’ When we were selling the game, on Reddit people said we should do that for free. I’d answer like, ‘You know, [sounds great,] but I’d also like some food,” Cieślar said on a Facebook call back in his native Poland. “My thinking if somebody already thinks you’re a Communist, and that you shouldn’t be doing a game at all, they’ll find any excuse [to tear you down.] Especially when it’s about money.”

One of the most quoted reprises in Marxism is an apology: “There is no ethical consumption under capitalism.” For socialists, it is a way to wash their hands of the grimy inevitabilities of modern life: typing a text message on an iPhone forged in a slag mine, belching more CO2 into the atmosphere during your morning commute, or packing a joint with the hopes that its contents don’t stem from violence or exploitation. But those are all superficially apolitical actions—the banal crimes of routine.

Credit: Failcore

So what does it mean for the rising tide of developers like Cieślar, who want to create video games that capture the progressive zeitgeist? Nearly everything about the video game industry is starkly capitalistic. While some governments around the world do offer development grants and the U.S. provides tax breaks that subsidize major publishers, the industry’s output tilts heavily towards laissez-faire. Steam and other digital retailers represent some of the freest markets in the world, and giants like EA and Activision have pivoted to a pay-as-you-go-model that intends to keep you obsessive and swollen with loot for as long as you’re within their grasp.

There is plenty of socialist art and artifice, but Marxist theories have rarely been applied to interactive entertainment, simply because it’s difficult to imagine a version of the industry that lines up with those ideals. But can these economic theories be put into practice when it comes to the development of video games? Can the promises of Invisible Fist line up with its praxis? Is it at least worth a shot?

“People want to believe in a [big corporation] coming to help you. Socialist agendas are harder, because it forces people to take responsibility for how the world is.”

Jan Cieślar

Ted Anderson broke ground on Pixel Pushers Union 512 (PPU512) in 2015 after digesting a documentary about the Wobblies—a forgotten labor movement in the United States active in the early 20th century. The Wobblies were proponents of a concept called “workplace democracy,” where workers were collectively responsible for every decision that happens within a place of employment. Anderson, a card-carrying leftist for a very long time, understood his limits—he doesn’t own all the means of production—but he did see an opportunity to adopt those ethics into a development studio.

“After almost 20 years of doing this I was like, why don’t we give it a shot? I proposed it to the team,” he told me. “If we got funded by a publisher we’d all accept the same pay level. We wouldn’t make money [until] after we paid for expenses and put money into a nest egg, so if that the company dissolved, that money would be divided equally among partners. Everybody would be making a percentage of the profits equal to another depending on who worked on what game.”

Today, every decision PPU512 makes, from game design principles to the decision to attend a specific convention, is the result of collective action. Anderson swears by the model from a pure diagnostic standpoint; he says that when you’re not worrying about bosses peaking over your shoulder, you’ll find that it’s a much leaner way to develop a product.

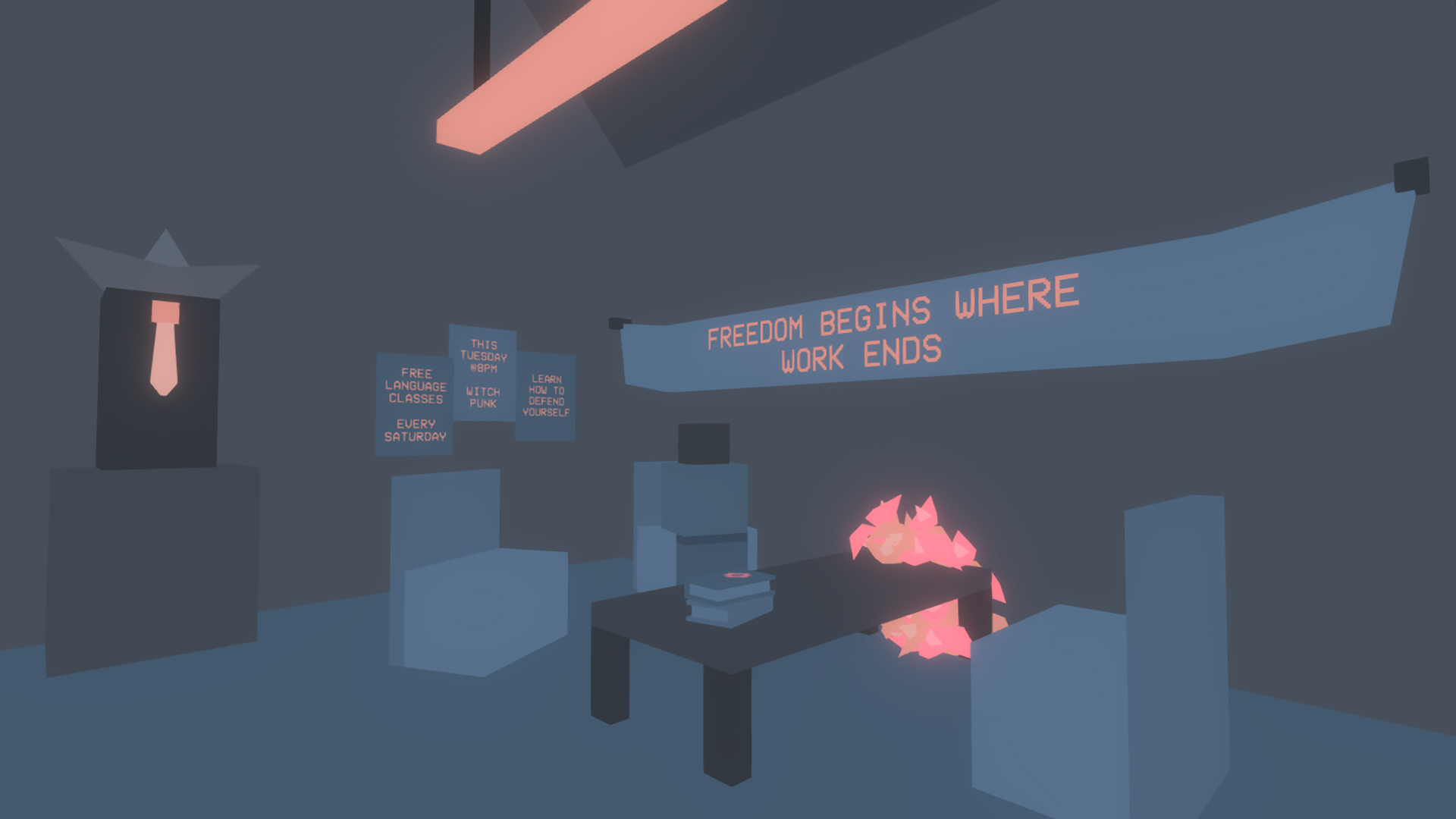

Credit: New Blood Interactive

But perhaps more importantly, the management-free environment lines up perfectly with the studio’s debut video game. Tonight We Riot is about as insurgent as pop culture gets: You take control of a gas-mask-donned, crimson-flag-waving revolutionary mob in an ugly, carcinogen-stained dystopia. You win by toppling the municipality—and killing a whole bunch of riot cops in the process. (And they are cops, Anderson said. Not stormtroopers, or paramilitary forces, or any other half-step you have in mind. He has no interest in tempering his vocabulary.)

Surprisingly, despite some of its more radioactive qualities, Tonight We Riot did find publisher support. Dave Oshry, at New Blood Interactive, will be releasing the game on Nintendo Switch in the not-too-distant future. This was the first catch-22 I was curious about. How does an overtly commune-like studio acquiesce the publishing rights of its proletariat-revenge fantasy to a profit-first third-party? Simple: You force that publisher to come to the bargaining table.

“While PPU512 is a worker owned collective and New Blood is not, I’ve agreed for New Blood to take an equal percentage as everyone else in PPU512, the same as if New Blood were just another worker,” Oshry said. “That allows me to run my evil capitalist regime while still adhering to Ted and company’s tenants of sharing the wealth and means and all that socialist goodness.”

Credit: New Blood Interactive

Anderson told me that he didn’t need to convince Oshry at all. New Blood was more than fine with PPU512’s ethical precedents, and Oshry himself says that while he doesn’t identify as an out-and-out socialist, he’s still extremely sympathetic to “unions, worker’s rights and trying in whatever small ways I can to bridge the ridiculous gap between those who have and those who have not.” According to Anderson, turning a profit with Tonight We Riot is certainly a priority, but given the sustainability upon which the rest of PPU512 is built, it’s not as much of a concern as it is for other studios who are put in the unenviable position of selling a game or closing up shop. “We have a tongue-in-cheek joke, what if socialism made us all millionaires?” he quipped. “That’s probably not going to happen, but it’d be funny nonetheless.”

The initial prototype of Tonight We Riot dates back to PPU512’s founding, in 2015. It’s only been four years, but the political climate is almost unrecognizable from what it looked like before the election. White nationalists see an ally in the White House, and many of their views have become normalized on cable news. On the left, the best way to distinguish yourself as an in-the-know socialite is to rebrand Red.

This is probably a good thing for the country—the Overton Window has never been wider—but I wondered how it felt to someone like Anderson. He started making the game when socialism, at least in America, was a lot less in vogue than it is right now. Is there any part of him that’s afraid that Tonight We Riot‘s timing will look skindeep?

“No, and I think it’s because I’ve always been very honest about it. I’ve never shirked from the [socialist] label. I’ve corrected people very early on,” he answered. “We got nominated to be at SXSW Gaming, and we were beyond excited. There were a bunch of interviewers going around, and this one guy asked me, ‘Does your mom know you’re a socialist?’ I’m like… yes? That’s a weird question. Did they want me to be violent about it? ‘No! No! Oh my gosh, delete the tape!’ It’s coming from a sincere place. It’s coming from my heart.”

Credit: New Blood Interactive

If anything, Anderson says the reignited interest in labor organization has been a miraculous boon for PPU512. (He was at a conference recently and asked if anyone had heard of the Wobblies before. More than half of the hands in the room shot up.) But obviously, a lot of that has to do with the cover he’s created for himself. Nobody can doubt the bona fides of a studio that has the word “Union” in its name. They are putting their money where their mouth is, and are promising to split up the dividends evenly between all parties.

I asked him how he’d feel if a developer was releasing a game with a similar political thrust as Tonight We Riot, but without the corresponding collectivist structure within the company. Again, he reiterated that he’s mostly happy that the word is getting out, any way it can. “I don’t think it’s the best option, but if done honestly, it’s not the worst option. Just… kinda skeevy, you know?”

David Cribb, a 24-year-old from Canberra, Australia, is staring down the exact same barrel. In his own words, he creates “radical leftist” video games, which are all available for free on his Itch.io account. In Post/Capitalism, you build a socialist utopia with the bones of a collapsed market metropolis. In A Bewitching Revolution, a pinko sorcerer sparks a coup in a swampy cyberpunk city. Currently, he’s hard at work at a Karl Marx skateboarding game. The first level will feature the philosopher grinding and kickflipping his way through a Wall Street–fashioned bank.

Credit: David Cribb

Cribb is an ideologue, and because of that, he doesn’t feel comfortable making people pay for his games—labor education and solidarity, he says, shouldn’t be bought and sold. But Cribb is also unemployed, and he could really use some cash. He has a Patreon, where a few trusty backers offer him monthly monetary encouragement in exchange for exclusive updates and early builds. Currently, though, he’s mulling the idea of putting his games up for sale, because he’s beginning to understand the nature of those who would call him out for such a supposed desecration.

Credit: David Cribb and Eli Cauley

“People who are more sympathetic to left-wing ideas understand that people need to pay rent. I feel like the only people who call people out for that are people who are already fully opposed,” he said. “The people who’ve had any issue with minor monetization are people who are never going to be convinced.”

It’s the irony of any social movement, the root of ethical consumption and capitalism. It is impossible to subsist outside the paradigm, and the demographic that hammers that point home the most are those who have a lot invested in ensuring that the status quo remains intact for as long as possible. You can operate within that economy if you choose, Cribb argued, but that doesn’t mean you’re of it.

Invisible Fist ended up falling short of its Kickstarter goals. Today, you can purchase the game on Steam for $15, and the team at Failcore is currently retracing its steps in order to find out what went wrong.

Cieślar told me he has some regrets about the game’s mechanics; if there is to be a second effort in the company’s catalogue, it probably won’t be a card game. But he remains steadfast about its politics, even though he’s uncertain if the radicalism baked into Invisible Fist’s DNA was part of the reason why it never found a publisher.

“I think people respond better to liberal agendas than socialist agendas,” he said. “People want to believe in a [big corporation] coming to help you. Socialist agendas are harder, because it forces people to take responsibility for how the world is.”

Cieślar told me he constantly reflects on a quote from the American literary critic and political theorist Fredric Jameson: “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” Video games are traditionally aspirational objects, and quite often, they too ask us to imagine the end of the world. Among all those apocalypses, surely there’s also room for the few developers who want us to consider Jameson’s alternative.

Header image: David Cribb

Luke Winkie is a writer and former pizza maker from San Diego, currently living in Brooklyn. In addition to EGM, he contributes to Vice, PC Gamer, Variety, Vox, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and Kotaku.