I was 12 years old the first time I killed Hitler.

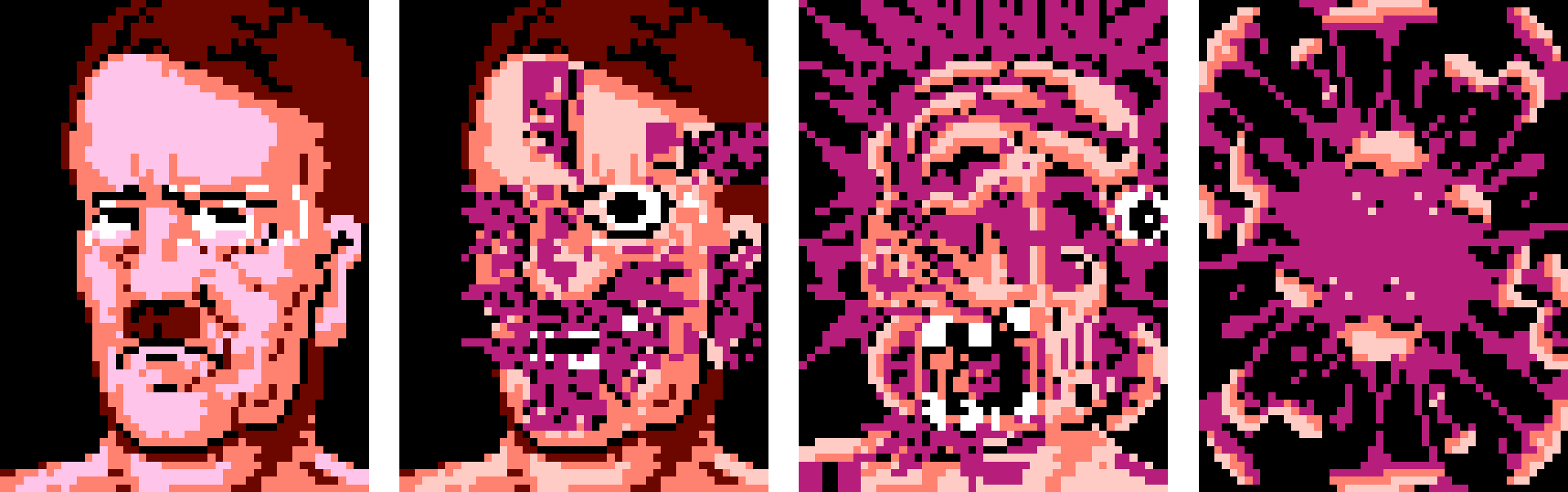

I was playing Wolfenstein 3D on my friend’s family computer during one of those sixth-grade sleepovers that ends with you waking up groggy and strung-out from the previous night’s Warheads and Doritos bender. My friend and I had spent the entire night shooting our way down corridors decorated with portraits of Hitler in profile, putting down dogs and Nazis with equal disdain. It was almost sunrise by the time we reached the final boss in the dungeon-like bunkers of the polygonal Reichstag: Adolf Hitler in a mech suit.

Credit: Apogee Software

Back then I spent several hours every Sunday learning about the Holocaust in Hebrew school. Each week my teachers would show my class black-and-white documentary footage of dead and dying Jews. We witnessed piles of starch-white bodies as lifeless as discarded socks. We witnessed living skeletons standing shoulder to shoulder in striped pajamas. We witnessed columns of ash ascending to the flat, gray heavens.

That we were watching these videos during the same year we were first preparing to become b’nai and b’not mitzvah sent a clear message, at least in my mind: Knowing deeply the horrors of how our people were slaughtered was just as important to being a Jew as knowing the Torah. There are many jokes about guilt being a motivational force for Jews, whether its source is the Old Testament G-d or our mothers. But the real guilt is somehow much more powerful and more omniscient. It’s survivor’s guilt on a genocidal scale, passed down through the generations.

During these lessons, my teachers barely mentioned Hitler, as far as I remember. They talked about the Nazis as a faceless army of the damned, they named the camps with cursed reverence, they whispered the word Kristallnacht. But when it came to discussing Hitler, there seemed to be a superstitious avoidance, as if saying his name in the mirror three times would bring him back to life. Omission gave him a weird sense of power over us.

That’s probably why 12-year-old me found it so satisfying to shoot Hitler in the face at the end of Wolfenstein 3D. It was a way to take back the power that my Hebrew school teachers were so willing to relinquish.

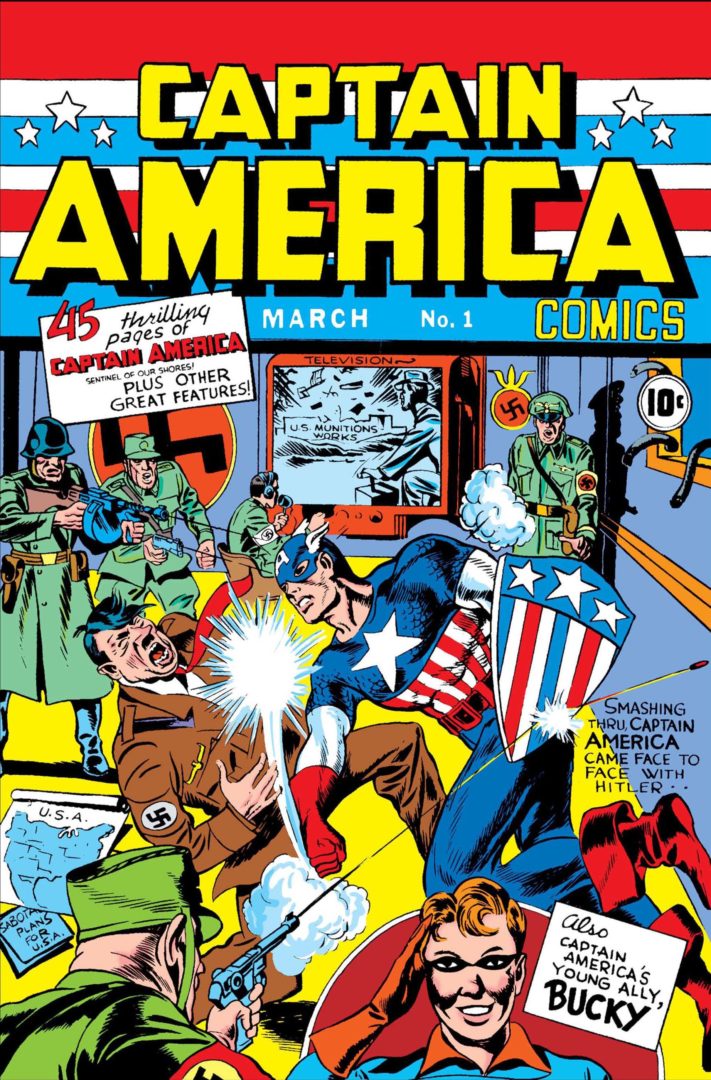

It’s difficult to pinpoint when the first revenge fantasy appeared. You could argue Captain America’s March 1941 debut—the cover of which shows Cap punching Hitler square on the jaw—is the first instance of creators imagining what it would be like to bring the dictator to justice. What makes this such a radical example is that, in March 1941, the U.S. hadn’t even entered the war yet. But, at that time, the full extent of Hitler’s atrocities were still unknown, and it would be four more years until he would take his own life, which turned stories about killing Hitler from wish fulfillment to alternate history.

What’s interesting to consider is whether, if not for this final injustice on April 30th, 1945, revenge fantasies against Hitler would be as prominent as they are in popular culture. What if Hitler had been captured and tried in Nuremberg? What if Hitler was publicly executed? What if the world had been allowed to confront him with his crimes? Would we—as Jews, as Americans, as Western democracy—still feel this overwhelming need for retribution?

These revenge fantasies come in many different forms. The Berkut, a novel by Joseph Heywood, imagines Hitler faking his own death, only to be tracked down by Soviet agents and kept in a cell as Stalin’s plaything. Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds sees the titular group of American operatives assassinate Hitler in a French movie theater, riddling his corpse with 9mm bullets from the Nazis’ own MP40s as the building burns around them and Shoshanna’s ghostly projection laughs eternally. It’s doubly sweet and poetic that most of the Basterds are themselves American Jews. Comic books have brought Hitler back to life many times, usually as a disembodied spirit finding a new corporeal existence in a supervillain or in the head of a gorilla.

Then there are the subtler revenge fantasies, such as 1973’s Hitler: The Last Ten Days (starring Obi-Wan Kenobi himself, Alec Guinness, as Hitler) and 2004’s German-made Downfall, which portray Hitler’s final hours before he and Eva Braun killed themselves. While these films don’t give us the catharsis of more overt justice, they do at least let us witness his demise. In stripping him of privacy in his final moments, we at least deny him that last triumph.

Video games are the only one of these mediums that wasn’t around during World War II, but they’ve readily (and graphically) imagined many ways for players to kill Hitler for decades. As younger me discovered, 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D casts Hitler as the final boss, decked out in a mech suit and armed with dual chain guns. Surprisingly, that wasn’t the first video game that let players murder Hitler. 1984’s Beyond Castle Wolfenstein from developer Muse tasked players with sneaking into Hitler’s bunker and setting off a bomb. The Japanese version of 1988’s Bionic Commando cast the main villains as futuristic Nazis (“Badds” in the American version) and Hitler (“Master-D”) as the final boss.

Credit: Konami

As an extension of the most popular Nazi-killing franchise in history, MachineGames’ Wolfenstein revival has a convoluted relationship with Hitler’s death. Taking place in an alternate universe where the Nazis won World War II after gaining access to ancient technology that gave them a military advantage, the new Wolfenstein series is notable in that actually attempts to build a believable world in which the Nazis have taken over. While Hitler’s presence is felt throughout 2014’s The New Order in the form of the maniacal and zealotic General Wilhelm “Deathshead” Strasse, who B.J. Blazkowicz stabs repeatedly at the end of the game, Hitler himself doesn’t show up until Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, which portrays him as a frail, ill, aging megalomaniac. Despite his physical degradation, Hitler is still a terrifying psychopath who shoots someone in the head just for calling him “Mr. Hitler” instead of “Mein Fuhrer.” (MachineGames takes the revenge fantasy of killing Nazis even further by canonizing B.J.’s Jewish heritage, casting it—and recasting previous titles—into a narrative tradition and revenge fantasy subgenre of Jews taking justice against the Nazis into their own hands.)

It’s not until Wolfenstein: Youngblood, the co-op spin-off featuring B.J.’s twin daughters, that Hitler dies, and his death comes offscreen, in past tense, with an offhand mention that B.J. finally killed him years earlier. While this hints that players will get the opportunity to enact their revenge fantasy whenever a proper Wolfenstein III comes out, this reveal in Youngblood will have undermined the impact of that moment when it arrives.

The game studio that has most fervently portrayed revenge fantasies against Hitler is Rebellion, which has let players kill Hitler across two different series. Sniper Elite V2 and Sniper Elite 4 each had a bonus mission that let players shoot Hitler and watch the bullet penetrate his skull in the pornographically violent, close-up detail of the series’ trademark X-ray kill cam.

But it’s Rebellion’s Zombie Army series that portrays the most outlandish journey to revenge against Hitler. In the first game, Hitler, facing the fall of the Reich, uses dark magic to resurrect the corpses of dead Nazis to create the titular zombie army. Not until Zombie Army 3 do players finally get to confront and kill Hitler, and only then by casting him into Hell. Zombie Army comes from a long lineage of Nazi zombies in pop culture—as if armies of living Nazis weren’t scary enough—but it’s the only one I know of that actually kills Hitler.

As much as I love the Zombie Army series, there’s something disingenuous about the revenge fantasy aspect of that final boss encounter. It doesn’t comprehend the rage and guilt that has stoked these revenge fantasies in the same way that something like Inglourious Basterds does. There is some historical basis for Hitler as a believer in dark magic and the occult, but Zombie Army doesn’t try to portray him as anything more than an evil sorcerer.

It’s unfair to single out Rebellion, though. The meme-worthy finale to Zombie Army 3 speaks to a larger disingenuousness in the overall subgenre of Hitler revenge fantasies, especially when it comes to how it’s portrayed in video games.

Credit: Bethesda

Maybe it’s a problem of context. Hitler, as he’s generally portrayed in video games, is a supervillain. He’s wearing a mech suit or leading an undead army. Even in New Colossus, Hitler’s crimes are generally unspoken, and his demeanor resembles that of a syphilitic mad king, ranting and raving and executing his subjects on a whim, rather than a strategic and charismatic dictator that ordered and manufactured genocide. It doesn’t help that the terror of the present, with its rising tide of nationalist conservatism, has begun to overshadow the horrors of the past. In drawing political parallels between New Colossus and the real world, The New Yorker critic Simon Parkin turned his lens on Trump supporters, MAGA lovers, and white nationalist Richard Spencer.

Killing Hitler is an easy choice. Who is more universally recognized as deserving of a violent death? But Hitler’s evilness is largely left abstract in video games, presupposing a knowledge and understanding of why Hitler’s death should feel so righteous. This abstraction divorces the act of killing Hitler from the fact that he ordered the murder of 6 million Jews and 5 million Slavic, Romani, black, gay, and mentally and physically disabled men and women.

When I kill Hitler (and Nazis in general) in video games now, I don’t feel that sense of righteousness that I think the developers want me to feel. The Nazis I kill in Zombie Army or Wolfenstein are just another version of the Locust Horde, the Covenant, or the Combine.

Credit: Rebellion

Perhaps ironically, the revenge fantasy that feels the most substantial is George Steiner’s controversial The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H. In the novel, Nazi hunters and Holocaust survivors discover that Hitler is alive and hiding in the Amazon. They find and capture him, but the journey out of the jungle is slow going, and they end up spending enough time for Hitler to go on a long tirade that forces the Nazi hunters to consider the parallels between his thinking and the idea of the “Chosen People,” as well as whether the state of Israel owes its existence to his actions against the Jewish people. Steiner, whose family escaped from Nazi-occupied Paris, asks the reader to confront Hitler’s vision of purity, justice, and fate, and how Jewish survivalism and unity is a direct result of historical persecution.

It’s that kind of complex reckoning with history, identity, and guilt that most Hitler revenge fantasies don’t seem able to or even want to acknowledge. When my Hebrew school teachers showed us footage from the Holocaust, I can’t deny that seeing these unimaginable atrocities gave me a weird sense of pride in the strength and endurance of the Jewish people. If anything, the lessons I took from Hebrew school and what these revenge fantasies teach me is that the fight against fascism is never-ending. Active resistance against fascism, on both micro and macro levels, should be a main tenet of Judaism itself, on par with performing mitzvot and following the commandments—especially when it comes to the fascism we practice. Killing a fictitious Hitler won’t fix the past, but maybe it can impact how we understand the future.

Header image: Zombie Army Trilogy, Rebellion

Michael Goroff has written and edited for EGM since 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @gogogoroff.