“Oi, you, what you lookin’ at?” sings Mark Healey over a lively electronic beat, his voice rasped and over-Cockneyed. On screen, two fighters, bodies flexing like strands of half-cooked spaghetti, flail their fists, occasionally bouncing their red boxing gloves off each other’s heads. “Want some do ya? ’Ave some of that. Bish, bash, bish bash bosh!”

It’s not the kind of game you’d expect from the creative director and co-founder of Media Molecule. He is, after all, a master of the complex development tools in Dreams, the studio’s latest release, which lets players draw, sculpt, animate and voice their own games. Search #MadeinDreams on Twitter and you’ll find remakes of Final Fantasy VII and Super Mario 64 alongside quirky platformers, music videos and original artwork. Healey could make anything he wants—but his goal has been to “introduce an element of silliness, a bit of comedy.

“That’s one of the things about Dreams for me—it’s an opportunity to play stuff that’s off its head.”

The absurdity of “Oi, you, what you looking’ at?” is matched by “Purple Pants Surprise,” his series of animations about a spindle-thin man with a birds nest of ginger hair, long back socks, neon underwear and an addiction to thrusting his hips in time with a thumping beat. The “surprise” is that the man is in for a grizzly end, his entire body fried to ashes by a bolt of electricity before he explodes in an orange cloud.

Healey’s work has always had a surreal streak. Before he got his first-ever home computer as a kid, a Commodore 64, he promised his friends he’d make a game called “Sex Invaders.” His breakout moment in the industry came after he made Rag Doll Kung Fu in his spare time while at Lionhead: For the cutscenes, Healey and his friends shot footage with a handheld camera in a park behind his house, speaking in fake Chinese accents (he later admits it’d be considered “un-PC these days”). One of the characters was called “Fat Bong,” and the actor in the credits is simply listed as “Kareem’s mate.” The game would go on to become the first non-Valve game on Steam, and Healey later earned a job offer from the Seattle studio.

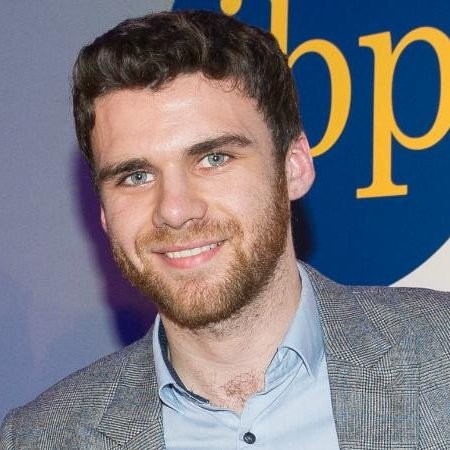

From looking at Healey, you wouldn’t guess he’s the source of these outlandish ideas. Not today, at least. He’s slumped on a purple sofa in Media Molecule’s offices, looking like he wants the black North Face coat wrapped around him to swallow him whole. He’s pale, and nauseated, and had to drag himself out of bed that morning. “I feel like I’ve been burning the candle a bit too much at both ends recently,” he says. When we spoke, development on the full disc release of Dreams was wrapping up. “That might explain why I’m feeling like this.”

But when he starts talking about his work—the weed-fueled parties with Fable creator Peter Molyneux, the early career struggles sleeping on office floors, the countless times he threatened to resign during Dreams’ development—he lights up. Wearing a button-down shirt with a pattern that defies comprehension, he hugs a Sackboy cuddly toy, and gives the character he helped create a piggyback ride in front of the studio’s wall of awards. He wrestles with a joystick as he shows me a Commodore 64 version of LittleBigPlanet that he’s built in his spare time. He strums chords on a guitar on the airy top floor of Media Molecule’s offices in Guildford, an hour south-west of London, and tells me about his son’s love of gaming—“he’s just addicted to bloody Fortnite at the moment”—over table tennis.

When you get past the shirt, he’s an understated man, and he speaks in a low, even growl. Despite helping build one of the U.K.’s best gaming studios, he says he doesn’t feel like a good manager—“It’s not that I don’t like people, I’m just a bit more introverted, I suppose”—and prefers to lead by example. He hates crowds, which make him feel “anxious and horrible,” and if he can get out of speaking at industry events, he will. “I have to get up on stage sometimes and do talks, but I fucking hate it, it makes me feel sick.”

He’s been “spoiled” by success, he says. “Ever since I started, I’ve only ever worked on things that were successful, so I’m lucky, really.” If he’d been fully in charge of Media Molecule, the company “would’ve been a fucking disaster,” he claims, but he happened to “hook up with good people.” When I ask him when he realized he was talented, or that his ideas were special, he bats away the question. “I’ve never felt that. I’ve felt like my main attribute is just being fucking determined. I’m not the best programmer in the world, but I have quite a lot of willpower. If I want to do something, I’ll find a way to do it.”

I think there’s more to it than that.

Healey spent his childhood causing mischief. School was “all about having a laugh with my mates”, he says, and what started as stealing biscuits in junior school graduated to throwing snowballs at teachers in high school. He was regularly hauled into his head of year’s office, but never got in any serious trouble. “I think she had a soft spot for me. I’ve got this really bad habit, I laugh or smile when I’m told off, I can’t help it, and it seemed to work on her.”

He chuckles now, and as he reels off anecdote after anecdote he grows ever more animated, grinning at the memories. It’s not hard to imagine a teenage Healey, while on Margaret Thatcher’s Youth Training Scheme (YTS, or “You’re Thatcher’s Slave,” as Healey called it), finishing off a weeklong programming assignment in an hour and then building a random insult generator. He printed a string of three-word expletives that had the whole room—minus the tutor—in stitches. Or on a later work placement at an architecture firm, where he was asked to transfer numbers from paper to a database. “I’m not fucking doing that. So I was like ‘yeah, yeah, okay’. They left me in this room, and I played Starglider all day long, and then I also changed all the prompts on the computer to be different, childish stuff.” He was sacked soon after.

Once, while at high school, he ended up in the local paper where he grew up in Ipswich, near England’s east coast, pictured outside the gates in support of a teacher’s strike. Or so the journalist thought, anyway. In reality, Healey just wanted “an excuse to run out of the class and cause a bit of trouble,” and thought the protest was against the teachers, not for them. Older students had organized a walk-out, and Healey caught wind of it. “We planned it all, and the head of year collared me and said: ‘Don’t you dare do this, otherwise you’ll be in a lot of trouble.’

“Obviously we just did it anyway. About 10 to 15 of us walked out, marching through after lunch, and we were pointing at all the people who hadn’t come, going, ‘Scab, scab, scab!’” he recalls in a taunting voice. He got a dressing down from the head of year, but the headlines about the strike impressed his stepdad, a “hardcore socialist” who hauled him off to an event celebrating Karl Marx. “All his mates caught wind of this strike thing, they were going, ‘Good on you mate.’” Healey spent the meeting reading a Captain America comic.

It’s clear that family motivates Healey. In a 2010 interview, he talked about the importance of making his mother proud, and he tells me he admires the fact she brought up him and his siblings on her own, without much money. But over lunch, he speaks of his disagreements with her over Brexit, and his disgust over some of the things she posts on Facebook. “I have to sort of overlook it,” he says. Healey, whose wife was in the U.K. on an Italian passport before the vote and has since become a British citizen, voted to remain in the EU, and says he “can’t bear to look” at political news anymore. (Over lunch, he describes how he’d use the powers of teleportation, invisibility and immortality to make Boris Johnson’s life a misery. “Every time he goes to talk, I’d kick the thing out from under his feet so he falls over.”)

When Sony bought Media Molecule, Healey used some of the money to buy his father a house. As a child, his dad—a plumber—doubted Healey would ever make any money in games. “As a teenager that was what I wanted to do, and he said, ‘You need to learn a proper trade. You can’t make money doing that’. I ended up buying him a house, actually. He’s dead now unfortunately, poor geezer.”

Having a son in his mid-30s—Lautaro is now 11—changed everything. Healey loves being a dad, but admits it caused some friction in his marriage. “Don’t go into it lightly,” he advises. “It’s awesome as well, really magical. But those first few years were a fucking nightmare. Just having to get up at annoying times, just worrying every time they’ve got a little cough, you’re convinced they’ve got meningitis.

“Since I’ve had him, I’ve become terrified of flying as well. I’ve been on so many aeroplanes now, the odds must be getting slimmer and slimmer. I know it doesn’t actually work like that. Once I’m on there, I don’t get shaky and sweaty, but it’s in my mind. ‘Oh, this could be it then,’ and when you get turbulence, I’m like ‘Oh, here we fucking go.’”

Healey has clearly passed some of his creativity and entrepreneurial spirit onto his son (the name Lautaro comes from the Native American word for “daring and enterprising”), who comes up with plenty of original ideas for school projects. “But I end up doing the work,” Healey says. “There’s been many a time when I’ve been up at three in the morning making some fucking project for the next day.” In contrast to Healey’s upbringing, Lautaro has “most things you could ever want as a kid,” but keeps coming up with business schemes. “He comes home with people’s trainers, and he’s charging a pound to clean them.” Pretty cheap, Healey reckons.

“Some people come into the games industry with the idea that you can design a game all on paper first, and then just make it… I think it’s more about diving in and starting, and then it speaks to you.”

As a child, Healey’s cheek came with creativity. He loved drawing—“We didn’t have a lot of money growing up, I never used to get loads of toys or anything, so I’d just draw”—and that passion transferred to video games the moment he made contact with them. The first game he ever saw was E.T. on the Atari 2600 as an uncle’s house. “I remember not really knowing what it was. I remember seeing a box under his desk where he had it set up, and it said ‘joystick.’ I was like, that sounds a bit dodgy. Sounds like a sex toy or something.” He became hooked when a friend bought a ZX81, and Healey found himself wondering exactly how the games worked. “You had games on cassette, and I figured the games lasted as long as the cassette was playing.”

When he found out his family were going to buy a Commodore 64 on hire purchase one Christmas, his main excitement was not for the games he was going to play, but the ones he was going to make. He taught himself to program in BASIC, developed games, duplicated them on cassettes, and sold them in the playground. He was obsessed. His math lessons were spent doodling sprites on square-ruled paper, and he began drawing a line through his zeroes to match the Commodore 64 Font. “My teacher used to hate me for that, because it means something very different in maths.”

He made “Agrophobia,” a “rude, crude” text adventure game set in three locations, which he still references on his LinkedIn profile. “I sold about three copies,” his profile says. “Well chuffed I was!” He made parodies of films or new games to entertain his sisters, too. Ghostbusters became “Ghoulbusters.” The Way of the Exploding Fist became “The Way of the Imploding Foot.”

While in art college after leaving school, Healey “spunked all my grant on a disk drive for my Commodore 64” and had to drop out. “I got a grant from the government to buy all the art equipment. You’d get £200, which you can either use sparingly, or, it was about the same price as a C64 disk drive. I knew I wanted to make games, and having a disk drive made a big difference.”

From a contact on his Youth Training Scheme, Healey met Christian Pennycate, who was making games for the ZX Spectrum, another early home computer. Pennycate helped arrange a meeting between Healey and Codemasters, the studio that would go on to develop the famed Dirt racing series. On the car journey up, it dawned on Healey that he was actually supposed to be pitching something, and when he arrived he opted for “Celestial Garbage Collector”: basically the arcade game Defender, but filled with litter. It went down like a bad smell. “I could tell they were like, ‘What is this idiot talking about?’” Instead, the studio suggested Healey make a Commodore 64 version of Pennycate’s latest game, KGB Super Spy.

Over the next six months, Healey battled for control of the family’s color TV—”my sisters would come home and want to watch Neighbours”—while programming the game, learning new skills along the way. He got paid a few thousand pounds for his six months of work, and during development, his mother began badgering him for rent money. “I was talking to a Codemasters producer, and she just grabbed the phone off me and started nagging down the phone like hell,” he recalls. “‘He needs some money!’ I was just like, ‘Oh, mum you’re going to wreck everything.’

“I got a check through the post next day, an advance. So she did good, basically. I had to give it all to her, but at least that means she wasn’t going to kick me out.”

Later, Healey and Pennycate set up their own development company for hire, working out of a “crappy little room” in Lowestoft, Suffolk. As Pixelkraft, they and a group of friends made a series of educational games, as well as racing game Network Q RAC Rally. It wasn’t good money, but it was easy—until their luck ran out. “That all went tits-up, and I was just like, ‘Oh no, the dream’s over.’ But I managed to salvage some of my work.” He shopped around through recruiters, picking up a gig at a studio in Cricklewood, London. Healey took on freelance work on the side elsewhere in the city and, for two weeks, worked full days at one studio, nights at the other, and slept on the office floor. “That just wrecked me. I remember going to the toilet, and doing a poo, and it was white. And I remember thinking, right, I’m fucking ill, this is not good, I’ve got to stop this.”

He was saved by an interview with Bullfrog, and for the next several years his career was closely tied to that of Fable creator Peter Molyneux, Bullfrog’s co-founder. “I’ve got a soft spot for him,” Healey says. “It’s just a chemistry, some people you really get on with. He’s been accused of being a bullshitter in the past, but it’s more that he just wants to please people, he’s one of those people that says whatever has to be said in the moment. I’d just take it with a pinch of salt.”

He learned a lot from Molyneux, much of which can be seen in Healey’s own management style: Molyneux just “let people jam, get on with stuff, and then he’d steer it and focus it. We were notorious for taking a long time because of that sort of approach, but we did some good games.”

Molyneux also knew how to throw a party. “He’d have two massive pots of chili, one that was normal chili, and the other one that was full of dope, basically. We had some very messy parties at his house.” At a birthday bash for Molyneux at a stately home, the Bullfrog co-founder turned up in disguise, with full-on movie-style makeup, claiming to be a cousin from Turkey. “He was lingering around, and a couple of people were just slagging him off, really bitching about him. He revealed himself, and they just looked so bad.”

Healey leapt up the ladder quickly at Bullfrog. He “boshed out” the SNES and Mega Drive graphics for Theme Park in a matter of weeks, rather than the months the team expected. Eventually, he was made lead artist on Dungeon Keeper, where he came up with the idea to replace the cursor with the Hand of Evil, which could pick up and slap monsters, and used an ex-girlfriend as inspiration for the creature called Horny. “Not because of the horny bit—it just had her jawline.”

At Bullfrog, he finally felt like he’d got a foot in the industry. He’d gone from “living hand-to-mouth” to making original games alongside Molyneux, one of the best-known British developers. He grew closer to his boss during EA’s takeover, which Healey says wrecked the studio by imposing a corporate atmosphere on what had been, up to that point, a relaxed, informal workplace. “It was horrible. They just completely ruined the culture.”

EA even banished Molyneux from the office before the end of Dungeon Keeper’s development. Healey and two others moved their work to Molyneux’s house for a full year, and when the game was finally finished, Molyneux, already ostracized from the company he founded, left to start Lionhead. It felt natural for Healey to follow.

He again shone as an artist and designer at Lionhead, but it wasn’t until he started to code once more that he gained wider recognition. It began during the experimentation for “Dimitri,” which would much later become Kinect’s “Project Milo” tech demo, showcased at E3 2009. Nobody knew where the project was going: Healey, for instance, wanted to simulate an entire city, but his programmers told him it’d be too hard. “That annoyed me. I’m like, ‘That’s not hard at all, it’s all smoke and mirrors.’ Because I had a bit of programming in my background, I was like, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to learn programming again.’ So it was more to piss off the programmers, just to prove my point.”

One weekend, Healey and his friends decided to make a kung fu film in a park behind his house, just for fun. They filmed it and, looking back on the footage, Healey decided it’d work as the cutscenes for a game—a game that would become the first-ever non-Valve game on Steam.

Credit: Mark Healey

Rag Doll Kung Fu started as a Street Fighter–style brawler with fixed sprites and animations. Healey’s colleague Alex Evans, who also co-founded Media Molecule, suggested putting ropes in the game for the characters to climb up and down. Healey built one such rope out of tiny sections and, on a whim, let it fall to the ground from a height. “It fell in a position that looked like a stickman. ‘Fuck, I could make my characters out of this rope.’ It did feel like a bit of a eureka moment. I remember going for a walk around the park thinking, this could be really cool.”

Healey built it all in his spare time, but Lionhead posted about the game on its website. Soon, Healey got an invite to the Experimental Games Workshop at that year’s Game Developers Conference. He’d never heard of GDC, and expected to show off his idea to a small group in a cramped room. Instead, he found more than 300 people waiting. “I was shitting myself—I hadn’t really planned a proper presentation.”

He winged it, and the room erupted. Among the audience were two developers from Valve who told Healey they wanted to put Rag Doll Kung Fu on their new PC gaming platform, Steam. Healey had never heard of Valve, either—“I lived in a complete bubble. Still do, really”—but Evans assured him the company was the real deal. Next thing Healey knew, he’d boarded a flight to Seattle (he lost his wallet in the process, and had to borrow money from Valve’s vice president of marketing Doug Lombardi) and was shaking hands with Gabe Newell.

Valve wasn’t the only interested party. Nintendo was keen, too. “That was totally surreal. I met up with all these execs from Nintendo, and they’re so strait-laced. I went into this room, and it was just these old businessmen standing at the back. I just felt so uncomfortable. I’m playing Rag Doll Kung Fu and there’s lots of silly stuff in there, stuff that’s probably a bit un-PC these days. We were doing pretend Chinese accents, making up stupid stuff.

“There’s complete silence. And then one of the cutscenes came up, and there was a bit of fake Chinese. One of the Nintendo guys suddenly laughed”—Healey mimics a booming belly laugh—”and then just completely went silent again. I don’t know if it actually meant something in Japanese. God knows.”

But Nintendo wasn’t willing to offer Healey a deal until the game was finished. “Someone who was more business savvy would’ve pulled it off, but I wanted an easy life.” The easy life, in this case, meant a deal with Valve. Rag Doll Kung Fu was officially coming to Steam, and Healey had the advance to prove it.

It wasn’t the last time Healey would hear from the Seattle studio. Soon after Lionhead shipped Black and White, Evans—who has “a brain the size of a planet”—got itchy feet. The company begged him to stay, and offered him free reign to do whatever he wanted. Evans set up in a small room with Healey and a few other collaborators, and they built a tech demo called “The Room.” Players would mould cubes of clay, and if they made the right shape, the clay would transform—Healey makes a “jooooop” sound—into an object, such as a sofa. The demo also featured portals that players could move between. “You could actually poke something through and see it on the other side,” Healey says. Sound familiar?

Valve, already familiar with Healey’s work, wanted to bring him, Evans, and David Smith, another Media Molecule co-founder, over to the U.S. “Portal was brewing… It seemed like an obvious match,” he says. “They schmoozed us, and were trying to convince us to work there. It was tempting—I’ve still got it at home, my offer and contract ready to sign.”

Healey, who says he’s a “very cautious person,” would’ve happily stayed at Lionhead, where he had a decent salary and never had to work too hard. (He refused to crunch, he says, and got away with it because of his relationship with Molyneux.) But as an alternative to joining Valve, the trio had discussed forming their own company to make original games. He went on vacation to mull it over, and by the time he returned, Evans had handed Healey’s notice in for him. Healey was told: “‘We’ve got to get out by tomorrow.’ I’m like, ‘What the fuck’s going on? Fuck it, I’ll just roll with it.’”

The trio, along with Lionhead artist Kareem Ettouney—who Healey now considers his best friend—gave birth to Media Molecule. Molyneux was supportive, Healey says, despite losing four talented developers overnight. He might’ve been upset if the group had taken jobs at Valve, but because they were striking out on their own, he was encouraging and full of advice.

“I haven’t spoken to him for a while actually,” Healey says, suddenly wistful. “I should say hello.”

The early days of Media Molecule went as well as Healey could’ve dreamt. The company met Sony director Phil Harrison and pitched a game based on a 2D physics engine Smith had built, introducing a character called Yellowhead. They made the whole presentation in the engine, which impressed Harrison. In Rag Doll Kung Fu, Healey had let players import their own graphics and make their own characters, and the team wanted the same level of user-created content in their new game. “Go further,” was Harrison’s advice, as Sony agreed to fund the team for six months.

And further they went. Healey wanted to make a full-on set of creation tools, inspired by his time as a child. He recalls his sadness when, while still at Bullfrog, he bought a PlayStation 1 and realized that he couldn’t make games on it like he had on the Commodore 64. “Suddenly I felt like it had been shut off. Dev kits cost a fortune, way out of reach of most people. So that set the seed in my head: You should be able to make games on consoles without having to fork out for big dev kits.” The PlayStation 1 shipped with a programming disc, he recalls, but it was “so lame, I remember thinking it was a crime.”

After some internal wrangling, the team ended up halfway between a proper game and a creation kit, letting users build their own levels for others to play. The engine turned into LittleBigPlanet, and Yellowhead turned into Sackboy.

Sony execs fell in love with Media Molecule’s work. They made Sackboy PlayStation’s de facto mascot at GDC 2007, showcasing LittleBigPlanet for the first time. “We turned up, and that’s when it all dawned on us,” Healey says. “We opened the doors and it was like something out of Lord of the Rings, where they have all those legions lining up. I remember really sweating. That was us landing properly.” It suddenly became easy to recruit: Everybody wanted to come and work on LittleBigPlanet.

The game was a roaring success, and Sony wanted to make the relationship between itself and Media Molecule permanent, approaching Healey and the other co-founders with an offer to buy the company. At first, he was conflicted. He’d seen how EA’s takeover of Bullfrog had ruined the studio. His instinct, however, was to jump at the “once in a lifetime chance.” With the money, he’d be able to afford a house, plus one for his dad. “It’s the sort of thing I never imagined happening to me,” he says. “So when the chance was there, I was like, ‘This is definitely going to fucking happen.’”

The money from the deal has nearly run out—“It’s not cheap to live ’round here”—but it reaffirmed how lucky Healey felt to have made it in the industry. He’s always felt, and still always feels, an “inch away from being homeless,” he says, but the deal allowed him to enjoy himself, and “reap a bit of harvest.”

“I just feel really lucky, to be honest,” he tells me. “Sometimes when I go back to Ipswich and I have a little wander around my old haunting grounds, it just seems so grim and banal. That’s probably not fair—but certain areas of Ipswich have really gone downhill. When I think about that, if I wasn’t doing this thing I’m doing, I don’t know how I’d cope with it all. I’m really lucky to be doing something I love doing and getting paid for it.”

After the deal, any fears Healey had over a repeat of the EA-Bullfrog debacle proved unfounded. If anything, work got better, because he no longer had to worry about what Media Molecule would be making next. “I hate prostituting yourself off to publishers, that’s not my thing really, so I thought, if I don’t ever have to do this again, fantastic. It was all about taking that stuff away, and focusing on making the games.”

LittleBigPlanet 2 was a “fattening out” of the original, and remains Healey’s only ever sequel. Leaving the series behind—LittleBigPlanet 3 was developed by Sumo Digital—was difficult, because it had defined Media Molecule up to that point. But it allowed Healey to concentrate on the game he’d wanted to make all along: Dreams.

It was, he envisaged, the creation kit he’d argued for during the early days of LittleBigPlanet. Healey began making games when he had a Commodore 64, and not much else. Dreams was made for those who have a PlayStation 4 and not much else, he says. “I’m sure there’s lots of kids out there that have got PlayStations and cool ideas, but they haven’t necessarily got PCs, and they don’t have the opportunity to go to university for whatever reason. I just feel like that’s a shame. We’ve probably got a lot of talent out there, and they just need a chance.

“I still think there’s a lot of kids that don’t have that privilege. Maybe it’s my stepdad’s socialist roots, this whole democratization of development.”

Dreams also feels like Healey’s creative process boiled down to its purest form. His ideas often arrive not in bolts of inspiration, but in simply “having a go in the first place,” he says. “Some people come into the games industry with the idea that you can design a game all on paper first, and then just make it. Maybe you can if it’s a simple thing, but if it’s something new, I think it’s more about diving in and starting, and then it speaks to you. You start with a basic mechanic and play around with it, and little accidents happen and they inspire ideas.

“Whatever you’ve got at the time, play around with it, tinker, and that’s the biggest inspiration for me. Especially the accidents. That’s one thing I’ve learnt over the years. God laughs at your plans, shit just happens, and you just roll with it.”

Dreams was in development for the best part of a decade before its release last month. In the beginning, the team didn’t acknowledge how ambitious they were being, Healey says—and the project only became more difficult as the studio added ever more complex tools. Each time they tweaked those tools, they had to change the story campaign, made entirely within the engine. “I can’t imagine that any other publisher would’ve given us this much rope. It’s stupidly ambitious. I think it’s a miracle it’s happening.”

Miracle or not, it’s been exhausting, Healey says, and has occasionally strained relationships at the company. “I can’t remember how many times I’ve walked out of the office. I’ve threatened to resign once a week or something like that. I never mean it. It’s just me being pissed off with something stupid.”

Occasionally, when Healey really wants to get his way, he does it by being a “complete miserable bastard.” But he’s stopped threatening to resign these days—he simply goes home and stews. “The pattern is, there will be something that annoys me, and then I kind of go, ‘I’m going home for a few days, I can’t handle this.’ And then I reflect and realize I was being a twat, and then I come back.”

Does he think staff get annoyed by it? “They get worried for me, because I get depressed and stuff. Or maybe everyone fucking hates me, I don’t know,” he says, laughing. “It’s possible.”

One of the things he’s most proud of is the fact the original co-founders have remained friends despite wanting, occasionally, to kill each other over creative differences. He recalls one incident in which he was sitting next to Ettouney, and they were trying to pick a color palette for a LittleBigPlanet level. “I’d adjusted the colors to what I thought was good, and he’d adjusted them to what he thought was good,” he says. “And I just have to say what’s on my mind. I was like, ‘It looks shit. I’m sorry, it literally looks like the color of baby shit.’ And he looked at mine and said, ‘No, that’s what yours looks like.’

“We were really annoyed with each other, getting sweaty and agitated. And it turned out they both looked exactly the same, but we were looking at them from different angles on the monitor, so it looked weird. It’ll be things like that.” Were the pair close to punching each other, I ask? “He’s much bigger than me, he’d pummel me into the ground. Maybe I’d get one punch in before I was killed. The worst that happens is we don’t talk to each other for a couple of days.”

Dreams has also made Healey more accepting of other developers’ ideas, he says, especially any from left field. “My gut reaction is ‘Fuck off, no way.’” Now, he’s able to walk away, think, and realize that he’s been stubborn. “It’s good that I can go back and reflect—some people can’t. In the past I would’ve had the tendency to say, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to do it all myself.’ Which is silly, because it’s not like I’m the master of anything.” He likens his role as creative director to “being in a room, and there’s loads of other people with clay, throwing it at the table. And I’m there trying to make sense of it all, try to keep it all together.”

Last month’s release of Dreams, which had been in Early Access since April 2019, is just one “vertex along the spine” of the game’s journey, Healey says. He’s excited about how it will be used in VR, and believes it could be a huge step forward for the medium. “You’ve got this relatively new medium, so let’s crowdsource possibilities. Give it to the PlayStation community… if you open it up to that audience, you’re going to get much wackier ideas.” He’s also keen on helping creators monetize their work, although those discussions are still ongoing. “Bringing money into things can often fuck things up. So we’ve obviously got to get that right, if at all. I hope we can.”

Media Molecule isn’t making any plans for its next game yet. For now, Healey is focusing on supporting Dreams long term. If the studio does make something new, “we’ll make it in Dreams, that’s the plan.” For a man so full of restless energy, it must be difficult to sit still without moving onto the next idea, I suggest. But Healey says he wouldn’t ever take a job at another studio. “That would just be torture. I’ve got plenty of room in here to express ideas,” he says.

“My next step would be retire, I reckon… when I can’t hack getting out of bed anymore. Retirement for me would probably mean making Commodore 64 games nobody is ever going to play. But no, I haven’t got itchy feet all. I haven’t got the energy to start another company, and it would feel pretty wrong as well. I’ve been here from the start, and it’s our baby. It would feel criminal to me.”

Besides, Healey has plenty of side projects into which he can pour his creative energy. He wants to make a vinyl record, he says, using his home recording studio. “Even if I just print one and have it in my own collection, just because you can. I can do it all myself, because then I can do exactly what I want. It’s good to work with people sometimes, to get pushback, but on this one I’m going to be completely self indulgent. I haven’t got illusions of being a rockstar—I’ll just have a piece of vinyl I can put on the record player and say it’s mine.”

Just before our interview is over, he remembers an idea for a game he’s “always had burning in the back of my mind.” It’s an amorphous beast: He describes it as the equivalent of a concept album in game form. “It’s got that gravitas of something [Pink Floyd’s] Roger Waters would do. Obviously that’s wishful thinking.” But what would that actually look like? “I don’t know. Off its head, probably,” he says. “I just love Roger Waters, and it’d be cool if someone could make a statement like that.

“Maybe I’d have a go at it in Dreams,” he says.

Samuel is a freelance journalist. When he first played TF2, he couldn’t work out how to fire his gun—until he read a troubleshooting guide. You can find him on Twitter @SamuelHorti.