The post-apocalypse is a fantasy of rebirth. It’s no coincidence that Fallout’s recurring motif of eyes adjusting to the light, seeing a new world and a new destiny, mirror that idea exactly. Rebirth is an alluring concept, especially to us humans so burdened with responsibility: Post-apocalypses grant both a freedom and a new frontier in which to indulge it. Look at Metro: Exodus and you’ll see the vibrant, chaptered landscapes of the genre, whether rust-punk oil tankers beached in the desert, Chernobyl-esque lost cities, or lush, canopied forests. But post-apocalypses rarely concern themselves with how humanity got there in the first place; nuclear war, pandemic, technology, or zombies all provide a speedy “event” and a context via which the dead world is remade, but the actual process of dying is almost invariably skipped over. All the more striking, then, are the rare exceptions to the rule: the games that show us beautiful worlds which have not been reborn, but are instead dying before our very eyes.

For Raphael van Lierop, creative director on The Long Dark and founder of developer Hinterland, dying worlds provide a significant fascination. “The idea of presenting a world that has been changed dramatically by some extreme event, and what that world might look like decades or even centuries afterwards, is so seductive—in a way it gives you a kind of blank slate to do whatever you want, without really needing to do the work to explain how things got to where they are,” van Lierop says. “For me, part of what’s fascinating about the idea of the apocalypse is, how does it happen? What are the subtle ways in which things change? What does the gradual descent look like? Could we be at the beginning of that long downward curve right now and not even know it?”

If anything, our love of post-apocalypses reflects an abdication of responsibility, a wish to skip over the ending and find a brave new world waiting for us. But as a “quiet apocalypse,” van Lierop’s The Long Dark, insists on giving us a slow, beautiful death. Inspired by the geomagnetic storms of 1859 and 1989, “The Flare” disables all electrical devices, causing your plane to crash on the island of Great Bear, in the far north of the Canadian wilderness. You are left to fight for survival, while above, an aurora, the eerie symptom of the geomagnetic event, bathes you in its cold light.

Credit: Hinterland

“Most of us, in our daily lives, are so divorced from the natural world that the most unsettling experience many of us can think of is to be lost and alone in the wilderness,” van Lierop says. “The feelings of vulnerability that come with the realization that you are at the mercy of a nature that doesn’t care whether you live or die is too much for most of us to bear.” He sees The Long Dark’s survival as both cathartic—“like facing a fear again and again in an attempt to master it”—and humbling.

In the game’s harsh Canadian wilderness, nature still thrives. As animals and predators begin to occupy the ghost towns of Great Bear, in some ways it can’t help but feel rightful, because this isn’t the reinvention of a post-apocalyptic world, but is instead a rebalancing of the scales, a reclamation. In this lies one of The Long Dark’s most bittersweet aspects: This beautiful, resurgent wilderness is killing you. Every day, the conditions of your survival grow fainter, and as your world dies little by little, a new one is taking its place.

“This is part of why Survival Mode features permadeath, and a series of systems that are tuned to lead to entropy at some point—eventually, you will die. There is no way to ‘win’ against nature. The best you can hope for is to enjoy a kind of hard-won equilibrium until that moment you make a mistake,” says van Lierop. “The idea that it may be irreversible, and that the future may not be brighter than the past, is a very hard thing to face, I think, and very germane to the world we live in right now. I think you can only explore those ideas in depth if you face the change as it is happening, rather than once it’s already done.”

This decline can also be seen in the shrinking, isolated communities of Great Bear, where if anything, the Flare was simply the final nail in the coffin. But most of all, it is reflected in the aurora, the iconic northern spectacle and arguably an aspect of magical realism: a mysterious, unaffected observer of the apocalypse, whose appearance in the sky causes animals to become more dangerous, blanketing the world in a ghostly light. But as van Lierop says, it’s also a symbol of nature’s power and the apocalypse’s geomagnetic origin, as well as a reminder of what humanity has lost. At its heart, the aurora is literally a beauty born from our dying reality.

“The sense that the aurora is magic ties in with the overall tone of The Long Dark. While I talk about it being grounded, the world and narrative also has this sense of Lynchian surrealism,” van Lierop says. “I think it’s more interesting when not all the questions are answered, and when things aren’t necessarily as they appear. Just like nature itself, it’s not necessarily for us to dominate or master everything by logic or scientific method. Some things are perhaps just not for us to fully know or understand.”

Credit: Mobius Digital

via Fandom user Sp33d3h0

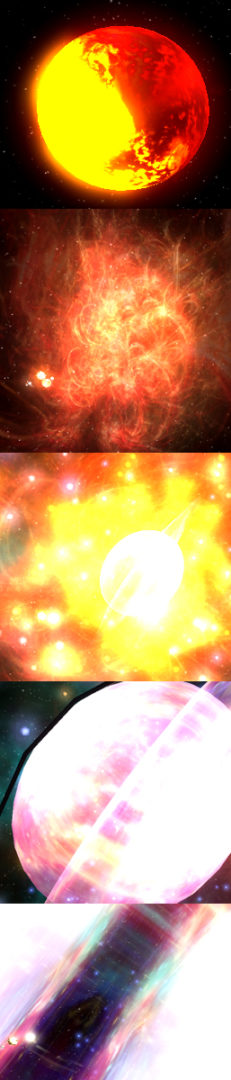

Another game that works to capture our powerlessness in the face of nature is Outer Wilds, a story centered around the cyclical death of a solar system. Where The Long Dark uses nature to create a harsh survival experience, Outer Wilds uses its autumnal aesthetic to juxtapose its themes of life and death, while also contextualizing the life cycles of the dying planetoids it contains. As a space explorer, you travel the system investigating these worlds and observe as they undergo their 22-minute lifespan—a clockwork procession that was as challenging for the developers to create as it is beautiful for players to witness.

“We spent a lot of our own time tweaking the rates of change to fit within 22 minutes,” explains Wesley Martin, art director on Outer Wilds. “For Brittle Hollow we tuned the resilience of each surface crust fragment as well as the launch rate of the volcanic moon which bombards the surface. For the Hourglass Twins we adjusted when the sand transfer starts and stops as well as its starting and ending heights on each planet. This allowed us to control the rate at which the sand rises and falls, and also let us create a delay at the start to give players time to fly from Timber Hearth. We hand-tuned every detail—from the types of trees to the large-scale color changes of sheer cliff walls, or the color of the sun as it filters through the atmosphere. Planetary motion is greatly exaggerated thanks to the miniature scale of the solar system, and this counter-intuitively lends the worlds a sense of grandeur by reproducing astronomical phenomena on a timescale that can be seen with the naked eye.”

Every one of the Outer Wilds’ planets is a microcosm for the death of the overall system, but strangely enough, that death isn’t a dark one. It could be due to the fact that by channeling a relaxing, autumnal aesthetic, accepting death becomes easier, as it is rationalized as part of a natural cycle. But I mostly think it’s easy to accept because the death itself is both gentle and beautiful. As the sun turns a deep orange, and shrinks before exploding outwards in an orb of expanding white light, it doesn’t feel like dying, but somehow closer to ascension.

“The supernova was one of the most difficult visual effects to create because it needed to feel massive and cataclysmic while also inspiring a sense of beauty and relaxation. We tried many different colors and shapes for both the explosion and the wave of light that engulfs the player before settling on the current style,” says Alex Beachum, the game’s co–creative lead. “The supernova is also one of the only ways to die that results in the screen turning white, as opposed to black, which helps it feel less violent than a sharp impact or asphyxiating in the void of space. The melancholic music that plays before the supernova is both a warning that the end is nigh and an invitation to find a good spot to roast a marshmallow and watch the light show.”

But death isn’t the darkest aspect of the supernova. I think it’s actually the unknown. As the sun explodes I picture the homely, rustic Hearthians facing this cosmic catastrophe, insignificant and blind to the larger machinations at work in their system, to the secrets often buried beneath their feet. It makes perfect sense that in a game about science, discovery, and curiosity for curiosity’s sake, its darkest existential theme would be the unknown. The supernova is a wonderful juxtaposition: It reminds us how small we are in the face of the cosmic mysteries that surround us, but it’s also deeply beautiful, an enticing mystery, a call to discovery and wonder, even when faced with mortality itself.

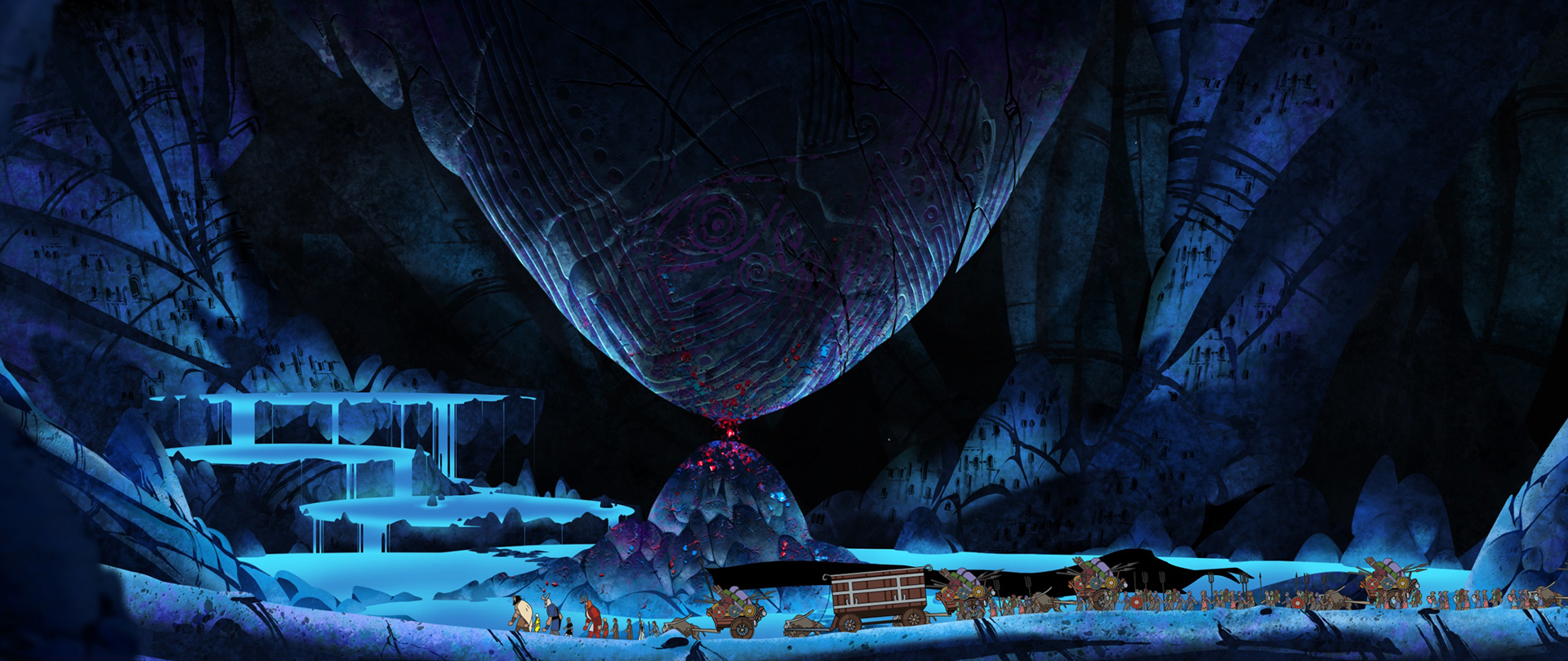

The Banner Saga, a trilogy of narrative strategy games inspired by Norse mythology, also explores the escalations of a dying world, as you do your best to save your people, all the while carrying a cultural record of your actions with you: a banner that flies in the wind above your caravan of survivors. The banner is the immortal record of your in-game choices, a tapestry of stories, akin to the Norse sagas. Because as with Ragnarök, the final apocalyptic battle of Norse mythology recorded in the Poetic Edda, the end of the world is a time for epic deeds. But as the world collapses around you and things grow desperate, the game shows the darker side to these tales.

Credit: Stoic Studio

“A key theme of Banner Saga is the duality of what we perceive in these heroic deeds, and what reality actually feels like,” explains Alex Thomas, writer of The Banner Saga and a founder of Stoic Studio. “One of the first things we identified was that there’s the fantastical, mythological Norse and there’s the gritty, painful, messy, real-life Norse. What would it be like if all these mythological things were happening to normal people—farmers, herders, rural villagers? How would it upturn the existing power structure? What would the aftermath look like? Those are much more interesting ideas to me than another story about the invincible chosen heroes who kill a thousand monsters and save the world.”

Sacrifice is a frequent theme in The Banner Saga. Just as with Ragnarök, the end of the world may provide a chance for glorious, immortal deeds, but the games’ characters are mortal. “The gods are dead,” is the first thing the game tells us, and throughout your journey you encounter their beautiful monuments, the godstones—effectively graves—looking on peacefully as the world burns around them, as if to remind you that no one is coming to the rescue. This absence leaves an opportunity for action, but the true bittersweetness of Banner Saga’s dying world is, ironically, that immortality has a mortal price.

Credit: Stoic Studio

“Everything has a cost. It really bugs me in stories where there are stakes presented but everything just works out fine, without sacrifice. The characters got everything but gave nothing,” reflects Thomas. “A hunter’s daughter wouldn’t be able to stand against a 20-foot, stone-skinned, deathless sorcerer-warrior, and the characters know this even though they have limited options. It’s a story about living through bad things and bad options and having to keep going.”

Though Thomas states that he leans towards the more cynical idea that stories rarely reflect the sacrifices of reality, I like to think that the Banner Saga also presents a kind of ascendancy: that through the actions and kindnesses we perform in life, we grow closer to divinity, and become our own gods. Just like The Long Dark and Outer Wilds, Banner Saga shows us that dying isn’t the be-all and end-all.

Whether it’s the illuminating fire of a supernova flipping the hourglass, a resurgent wilderness and an apocalypse-wonder hanging in the sky, or a chance at immortality, at being remembered, dying worlds will always be uniquely positioned to provoke beautiful ideas, never in spite of their darkness, but because of it.

Header image credit: The Long Dark / Hinterland

Sean Martin is a poet and game journalist living in the South West of the UK. He has written for Wireframe, Eurogamer, PCGamer, PCGamesN + many others. He writes about varied subject matter, from climate change to rat representations in games. You can find him rambling about anime and Total War on Twitter @LoreScavM.