On August 4th, 2019, the indie video game website itch.io crashed. Thousands of developers tried to upload games at the same time in a rush to get their work online before the deadline. The servers couldn’t take it, and the site became unresponsive for around two hours.

All the games were made in just 48 hours. They were short, simple, and often felt like they were held together with string and tape. But that’s the norm for game jams: short contests where participants flex their creative muscles and churn out a game in a short amount of time, all based around a single theme.

What set this game jam apart was its sheer popularity—over 7,000 teams from around the world, made up of hobbyists, students, and game industry professionals, worked through the weekend to try to rise to the challenge of the 2019 GMTK game jam. Mark Brown, creator of the YouTube channel Game Maker’s Toolkit, organized the competition.

The theme was a single phrase: “Just One.” It was up to the contestants to decide what that meant.

The contest has no prize. Winning it doesn’t even come with any large amount of exposure or prestige. The only honor is that its top 20 games will be analyzed in a Game Maker’s Toolkit video.

With grit, determination, and presumably an abundant supply of caffeine, over a third of the contestants managed to get a game completed and submitted.

“The themes set for the GMTK jams really set them apart from other jams. I find that they bring out new ideas for games that you wouldn’t have been able to think of usually,” said Matthew Watson, a college student who took part in the jam. “The theme set for each GMTK jam challenges you to think about the way you design a game—coming up with the ideas for it and refining those to a good concept for a game.”

Credit: Matthew Watson

This was the second year that Watson took part in the jam. In 2018, when the theme was “GENRE, but you can’t MECHANIC,” Watson produced the game Allocation, which was a Metroidvania without a connected world map. Instead of tracking your way through consistent world, players had to continually build and rebuild paths to get themselves where they need to go.

“I wouldn’t have necessarily thought of an idea like that under normal circumstances,” Watson said.

He, like many others, decided to join the GMTK jam because he follows Game Maker’s Toolkit on YouTube.

“There are a huge number of episodes on a variety of topics covering all sorts of aspects of game design,” said Watson. “My favorite videos are probably the ‘Designing for Disability’ series, which covers various design decisions to consider to make sure games are as accessible to as many people as possible. When I’m making a game, I always try to think about what I learned from those videos.”

More and more people are turning to YouTube to educate themselves, and Game Maker’s Toolkit has become a must-watch channel for the newest generation of developers. Because of this, Brown has had an undeniable influence on how these developers design games.

A former game journalist, Brown started creating YouTube videos in 2014—not because he wanted to become an influential figure, but because he knew there was an audience for videos about gaming.

“It definitely feels like more and more people are turning to video for gaming content, so I decided that it would be smart to learn how to make videos and get a hold on the whole YouTube thing before the bottom fell out on traditional games journalism,” Brown said.

Credit: Nic Magnier

While most gaming content is focused on playing games, cracking jokes, or sometimes just making top 10 lists, Brown took inspiration from something else entirely: video essays about films. He decided to port the format, popularized by channels like Tony Zhou’s Every Frame a Painting and Evan Puschak’s The Nerdwriter, over to his own area of interest.

“I am endlessly fascinated about game design, so the videos are just an excuse to research, think about, and explore ideas I want to know more about,” Brown said. “I’d be perfectly happy ending it after the research phase, but actually making the videos is how I get paid to keep doing this, so I’ll keep on making them!”

The resulting videos give viewers a deep dive into games to figure out what makes them work so well for players. He dissects the mechanics to figure out how a game achieves the things that everyone likes about it.

As a result, Brown’s videos end up instructing his viewers in how to make a better game.

His channel’s 121 videos all take similar close looks at games from every genre, covering subjects like how Cuphead’s boss battles are designed to challenge players without being unfair, or how series like Uncharted, Dark Souls and Super Mario keep players coming back for more without resorting to cheap psychological tricks like limited-time rewards or weekly challenges.

“I really hope that people take a more critical look at the games they play. That they don’t just passively consume games, but take an active role in thinking about why they do and don’t like the games they play,” said Brown. “I also want to highlight the super smart stuff that game designers are doing, and reveal game design as a craft and potential career choice.”

The videos’ depth and insights steadily gained Brown a following, with his channel attracting more than 100,000 subscribers in less than two years. He broke the 500,000 subscriber mark before the channel’s fourth anniversary.

It’s not the largest YouTube following, but it’s not through sheer numbers of subscribers that Brown gained his influence. It’s who follows him. Industry professionals, independent developers, and aspiring creators steadily joined the ranks of Brown’s fans.

Credit: Levi Moore

Their appreciation for his work is clear: viewers contribute over $10,000 monthly to Brown’s Patreon account, letting him earn a steady living making videos. For some followers, Game Maker’s Toolkit is one of the only resources they have to learn how to make games.

“I’m especially heartened to hear that GMTK is popular in places around the world that don’t offer actual courses in game development,” Brown said.

Brown’s effect on the industry can be seen all over.

“Accessibility modes in various games have been implemented based on my Designing for Disability series,” Brown said. “The level generation in Dead Cells is partly based on my work on Zelda dungeons, and plenty of indie devs have told me they’ve used GMTK to help them with their designs.”

Brown has spoken about game design at universities and has even been brought in as a consultant for a few games, but he says the details on those projects are “all NDA’d up the wazoo.”

“I also know my videos are watched by the biggest game studios and that designers on some huge [triple-A] games have used my videos for inspiration,” Brown said, “but I’m sworn to secrecy on all of those!”

With a growing number of professional and aspiring game designers following his channel, running a game jam was a perfect fit. It wasn’t Brown’s idea, though—fans on his Discord server asked him to run the contest.

“The idea had never really occurred to me before, but I thought I’d give it a go and see what the response was like,” Brown said. “The number of people who took part and submitted really blew me away, and the whole experience was really fun, so I decided it definitely needed to become an annual part of the channel.”

The first GMTK Jam was held in July 2017, with a theme based directly on a video he had made a year prior: “Downwell’s Dual Purpose Design.”

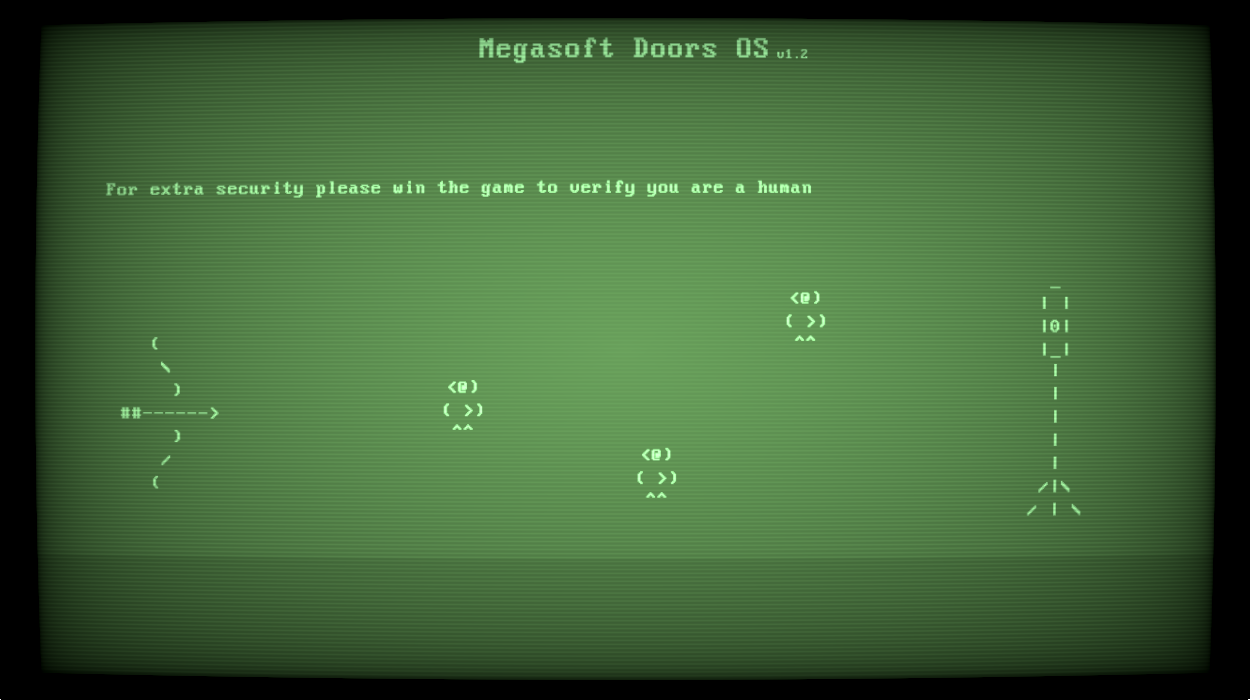

Credit: Nic Magnier

Brown described the arcade roguelike as “one of the most elegantly-designed games I’ve played in a long time” because of how everything in the game—from jumping to shooting to enemies to gem collecting—serves multiple purposes at once. The jam asked people to create a game around that design philosophy.

The jam was hosted on itch.io, and with 748 games submitted, it became the biggest game jam that the site had ever seen—a record that the Jam would break again in 2018, and a third time in 2019.

One regular participant, Nic Magnier, worked at Nintendo of Europe for over 10 years. When Brown started creating videos about game design, Magnier followed his channel.

“I think it is really helpful for many viewers to understand how to be analytical and how to deconstruct design concept,” Magnier said. “For me, it is very valuable to better understand games or genres I usually don’t play.”

Magnier left Nintendo to work as a senior designer at a smaller company, Keen Flare, in 2016. That same year, he started taking part in game jams. He found that the quick turnover to be a breath of fresh air compared to the daily slog that he’s sometimes experienced while making games professionally.

“Developing a game can be quite lengthy nowadays, so it can feel that the game you are developing doesn’t really progress which can be demotivating,” Magnier said. “Taking part in game jam is often a big morale booster because you can ship a game in a short amount of time.”

Magnier’s 2017 submission, a space shooter called Void, kept players blind unless they used their lasers to light up the levels. The next year, he submitted a game called Fish, a match-3 puzzle game where the matched blocks get frozen in place instead of disappearing from the board.

Both of these entries were chosen among the top 20 games of the year’s jam.

“It is very rewarding to be picked as one of the best games in the jam, and a bit surreal to happen twice in a row, especially when there are so many participants,” Magnier said. “But in a way, this is also validating. It is always difficult to self-evaluate in any creative field, because you always compare your work with its ideal version. So, having someone that is known for their taste and their analytical thinking pick your creation and show it to the world, it is a great motivator.”

Credit: Nic Magnier

Magnier’s submission for 2019, Chronodog: Earth Defender, was well-received but didn’t make the cut.

“After finishing the game, we were really proud of it, and really enjoyed seeing people playing it,” Magnier said. “But I knew that the game design didn’t have the special something to be at the top, especially considering the amazing games that was made this year.”

An astounding 2,637 games were submitted to the 2019 game jam, enough to put its popularity on even footing with the longest-running game jam, Ludum Dare. It proved to be more than itch.io could handle, forcing Brown to extend the deadline by one hour and accept some submissions over email.

“It was incredibly stressful at the time, but in retrospect I guess it’s a pretty clear indication of how popular the jam was,” he said. “Itch says it has fixed the issue, so fingers crossed the servers hold up in 2020.”

For four days after the jam ended, users played through the thousands of games and rated them in three categories: design, adherence to the theme, and originality. Brown then played through the top 100 games, and made a video featuring the 20 games he thought stood out the most.

One featured game, Buddy System, has players controlling a pair of robots who must share a single power cell, maneuvering themselves into positions that let them toss the cell back and forth as they navigate through increasingly-difficult puzzles. Another, Intercom, had players instructing a character how to navigate traps by using nothing but beeps through an intercom, forcing players to invent their own morse-code-like commands on the fly as they frantically try to guide a blind man through a lab full of bottomless pits and electric fields.

If those games sound unusual, that’s the entire point. Brown said that while other popular game jams often center on abstract concepts like “waves” or “underground,” he tries to force creators to design games that are different from the norm.

“I generally try to find themes that are more like game design challenges,” he explained. “They should put developers under intense restrictions, and force them to design around problems. But also, the theme needs to work with a large variety of games and genres, so the prompt can’t be something like ‘one jump’ or ‘no movement.’”

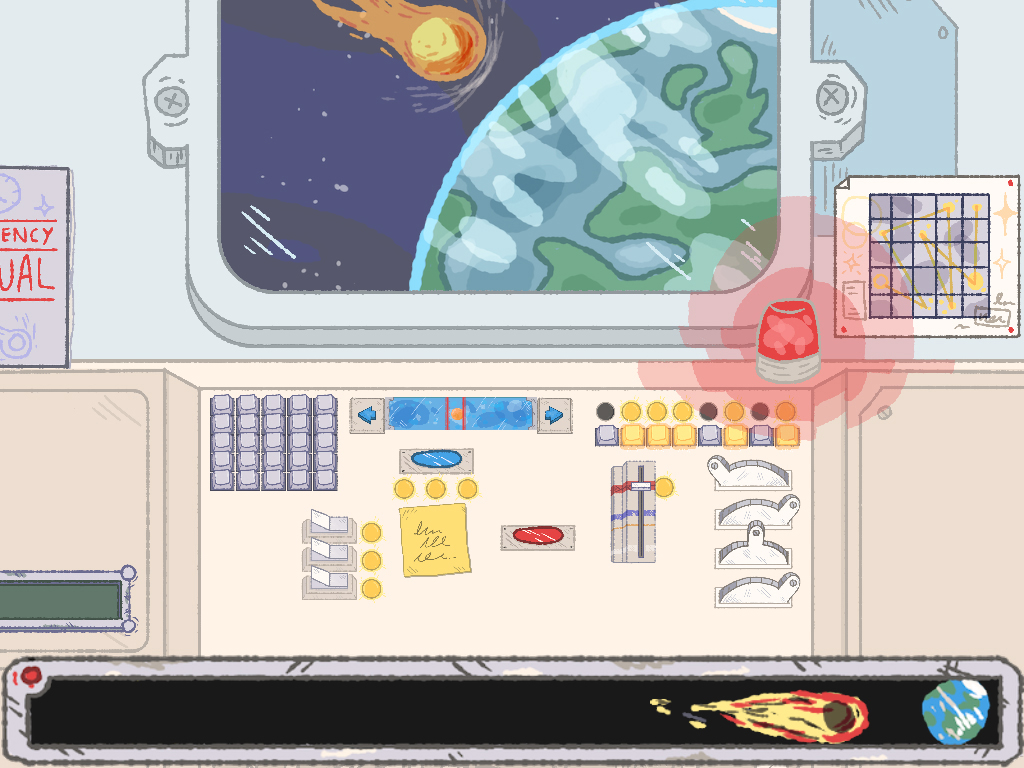

Credit: J.J. Morgan

It might seem surprising that so many inventive concepts can be dreamed up and created in just 48 hours. Magnier, however, believes that the time limit helps spur creativity.

“Game Jams are a great way to train your creative muscles. You have to think fast but also very pragmatically,” Magnier said. “I tend to overthink when I design games because I want to find the perfect ideas. You cannot overthink during a Game Jam because you don’t have time for it. You have to make a game fast. This is very liberating.”

Levi Moore, whose humorous game Only One Minute Before Restart was one of the 20 featured games from the 2019 jam, agrees with this idea.

“The time and theme constraints mean that you don’t have time for too much planning and second-guessing yourself. You just have to trust your gut feeling, work hard, and hope for the best,” Moore said. “The worst that can happen is that nobody plays your game, you learn what not to do and try again next time.”

Moore, an independent developer and teacher who lives in Denmark, has been making games since he was 12 years old and dreams of one day owning his own games studio. He entered the 2017 GMTK jam, but his entry didn’t manage to make the cut. He says that his win in the 2019 jam helped him feel like he’s making progress towards his goal.

“To be showcased in the video is validation that my hard work is paying off, which feels great,” Moore said.

Credit: ProdigalSon, Drums, Chevy Thompson

Moore, like Magnier and Watson, learned about the jam by watching Game Maker’s Toolkit on YouTube. He says that both the channel and the game jam have helped him become a better game designer.

“The YouTube series has helped me be more analytical when playing games, which helps me with my own games,” Moore said. “Something I have learned from the jams I have participated in is that simpler gameplay is sometimes better. When teaching the player how to play, it is a good idea to introduce one new mechanic at a time. Games with lots of mechanics that are dependent on each other, and can’t be isolated, quickly create a high learning curve and barrier of entry.”

Brown, for his part, loves that his channel is teaches and inspires creators, but he knows his limitations. He made sure to point out that his views aren’t any kind of be-all, end-all advice that will always result in an amazing game.

“Something subjective and artistic like game design is hard to teach, compared to fitting a boiler or changing a tire, so I hope that people take multiple viewpoints, and critically think about the views in my videos before they do anything with them,” said Brown.

Even with his modest view of his own teachings, Brown hopes that his work will continue to inspire game creators.

“If I could encourage indie, student, and would-be developers to be more thoughtful about elegance and simplicity in game design, that’d be great,” Brown said. “I’m always heartened to receive feedback from younger gamers who have said that GMTK has helped them better understand the games they’re playing, or even inspire them to get into games themselves!”

Header image: Door Knocker, the 12th place finisher in this year’s GMTK Game Jam, created by Something We Made.

Phillip Moyer is a Vegas-based journalist and lifetime game junkie. He grew up reading games magazines and chose his career path in hopes of one day writing for them. In addition to writing for EGM, he has been published in TheGamer and TouchArcade, and works at a local news station.