In late 2015, Reid Young, the CEO of Fangamer, boarded a plane to Japan, where he’d work on an upcoming documentary project and meet with representatives for the team behind Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night. At the time, Fangamer was already seven years old, but it had a reputation as a small company on the rise. As one of several gaming merch sites that had sprouted up in the wake of a more mature Web, the company hocked well-designed (if unlicensed) T-shirts and enamel pins for cult games of yesteryear—especially the offbeat JRPG Earthbound. Over time, however, the site became known as a reliable partner for fulfilling Kickstarter backer merchandise for notable projects like Double Fine’s Broken Age, which contributed to its success and ultimately led to famed Castlevania director Koji Igarashi tapping the company for Bloodstained’s hugely successful crowdfunding campaign.

On his flight to Japan, Young reflected on the massive year that his company had notched up to that point. “I remember thinking that Bloodstained was a huge deal, that even though it had been exhausting, it was definitely fueling our growth,” Young said. “I remember thinking, ‘Okay, if we can get past this, we’re definitely going to find a more sustainable way of doing things, because this definitely isn’t that.’”

Shortly after he landed, Young decided to check on the company chatroom, just to see how things were faring in his absence. Much to his surprise, he discovered that Fangamer was undergoing a crisis, and there was very little he could do to help. “Everything was basically on fire,” he said with a laugh.

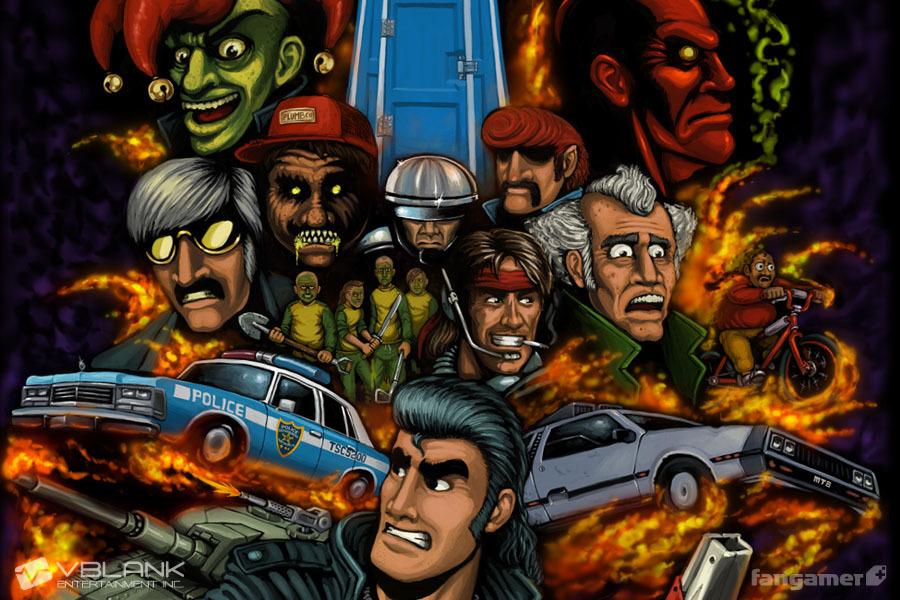

While the details took some time for Young to sort out, in hindsight the problem, and what spawned it, were very simple: A few years earlier, a young game developer who traveled in the same circles had reached out to ask Young if Fangamer could fulfill his Kickstarter. Since the two men knew each other from the Earthbound fan community, Young had agreed without no hesitation. As its release grew closer, the dev had asked the site to put a few shirts up for sale to help boost the game’s profile. But once Fangamer’s line of merch for the title actually launched, all its stock sold out in a matter of hours. While Young was en route to Japan, droves of disappointed fans were clamoring for a reprint, clogging Fangamer’s system with preorder requests for the next batch.

The developer Young had met with years before was Toby Fox, and the game that was leaving fans ravenous for merch was, of course, the indie darling Undertale.

“Nothing like that had ever happened before… It really did change pretty much everything for us,” Young said. “It’s not an exaggeration to say that it changed our entire company almost overnight. We’ve worked on bigger projects since then, but nothing quite as unbelievable as how Undertale performed right after its launch.”

In some ways, Fangamer’s origin story is as unlikely as the game that catapulted the company into the limelight. As a middle-schooler, Young was an enthusiastic fan of the then-obscure JRPG Earthbound, but he found it difficult to find other similar-minded souls on the primitive, pre-Google internet. To solve this problem, he created a fansite for the game in 1997 and purchased the domain Earthbound.net in 1999. Though the site’s name later changed to its more famous version, Starmen.net, it eventually became known as not only the online hub for devotees of the works of Shigesato Itoi, but as the poster child for the unbridled creativity that forms the heart of fan culture. Users of the site produced many enthusiastic amateur endeavors over the years—including Fox’s now-famous Halloween ROM hack—but they’re best-known for their acclaimed fan-made translation of Mother 3, which was helmed by the site’s co-founder, Clyde “Tomato” Mandelin.

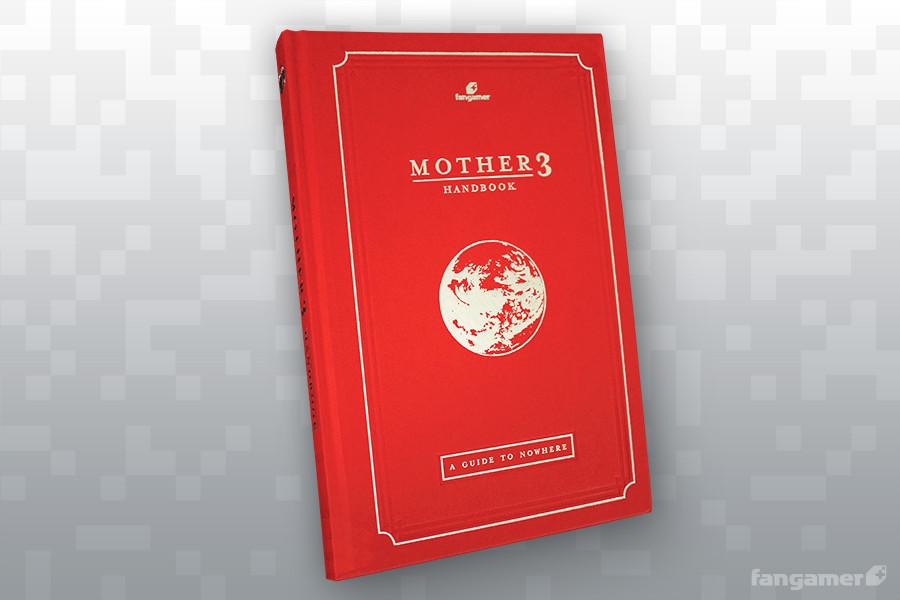

As work began in earnest on the project in the mid-2000s, the community decided to embark on what Young calls a “dream project”: producing a “player’s guide” for Mother 3 in the image of the one that Nintendo created for its ill-fated Earthbound marketing push in the West. That book ended up becoming one of Fangamer’s very first successes. “We started taking preorders for the book around the time Fangamer launched in August of 2008, and I remember Google actually shut us down,” Young recalled, laughing. “Back then, we had to use Google Checkout, because Kickstarter didn’t exist, PayPal was different. Within the first 12-hours, they said, ‘Hey, we have to shut this down, because you guys can’t bring in this much money.’ It took a week of bargaining and negotiating to unlock our account.”

Though the high profile of the hotly anticipated Mother 3 fan translation gave Fangamer an early boost, according to Young, the very idea for a video game merchandise site grew organically out of the community. Like a lot of icons of the early gaming internet, including the Flash portal Newgrounds, Starmen.net struggled to pay its mounting server fees by selling ad space alone. After a particularly brutal stretch, Young and others in the community decided to sell some swag to help keep the lights on, including a few T-shirts and a mug or two, recruiting some talented artists from the forum to contribute designs for these goodies. While Young remembers the initial rush of seeing the products his friends created as physical objects for the first time, he also recognized the limitations of the services they used to make them. In particular, he recalls admiring the Katamari Damacy shirts that the eccentric software company Panic put out in the mid-2000s as rare examples of tasteful gaming apparel.

“When we started to discuss making Starmen into our full-time gig—I was struggling to do freelance web design then—the original concept was to take what we had done for Earthbound, in terms of a community, and apply that to other games, like Phoenix Wright and Chrono Trigger,” Young said. “Well, the ads weren’t paying the bills, so we thought, ‘What if we took the kinda-crappy print-on-demand stuff we’re making on CafePress, and we did it at a much higher-quality?’ And that was kind of the genesis of it. When we made our first screen-printed shirt, that was when we were like, damn, we can really do something with this.”

From the very outset, Young and the rest of the early staff knew that gaming titans like Nintendo were unlikely to sign over their licenses to a brand-new company, so they endeavored to try to be as “respectful” as possible with their designs. The world of unlicensed nerd merch is a veritable minefield for small companies, where litigious rights-holders often send cease-and-desist letters to homegrown Etsy shops. In its early days, Fangamer set some ground rules: Unless they managed to get their hands on a license, they would never carry any designs that even hinted at copyrighted material.

“It’s the difference between carrying a shirt that says ‘Link’ or ‘Hyrule,’ and one that has the Triforce on it,” Young explained. “The first two are obviously the property of Nintendo, but the Triforce is a Japanese cultural symbol that predates the Zelda franchise. So, to me, that’s fair game… I think having those constraints ultimately helped us. We [avoided infringing copyright] at first because we were scared, and we didn’t want to be in the line of fire, but eventually we realized that, based on the feedback from our customers, they appreciated the subtlety of the designs that resulted from those constraints.”

“We hear that all the time,” added Noah Lane, Fangamer’s director of licensing. “People like to wear our shirts out in public, and people will compliment the artistry of the design without even knowing it’s from a video game. That’s really what we aim for.”

Once Undertale exploded, however, the company decided to use their newfound influence and capital to seek out the licenses themselves. After Young arrived back from Japan, the company scrambled to produce enough goods to sate the slavering fanbase, which continued to snowball in size in the interim. When Fangamer finally released the second wave of merch a few months later, Young couldn’t believe the numbers. “I thought there was a glitch in Shopify,” he said. “Undertale had become just an incredible phenomenon.”

designed by Andy Webb.

But while it certainly boosted their sales, the company now faced an interesting dilemma: Fox had never given Fangamer exclusive merchandising rights, but as the sole carrier of licensed Undertale products, Fangamer was now an unofficial steward of the game, which meant that it had an obligation to police the deluge of knock-off products that assailed the shores of online retailers like Amazon. Given that much of the store’s revenue still came from its own unlicensed designs at this point in time, Young felt that the company needed to approach this new directive with certain guidelines in mind, lest they risk becoming hypocrites.

“Toby and [Hollow Knight developers] Team Cherry have been pretty laid back about it, to be honest,” Young said, adding that Fangamer takes context into consideration with regard to copycat products. “We always said if you want to make something just for you and your friends, that’s fine. A lot of the time, it’s just a kid who wanted to buy a copy and just left the Redbubble page up or whatever, or who paid a friend to sew a plush. Obviously, we don’t take issue with that. But it’s gotten worse over time, for sure. There was a Chinese factory that set up a site dedicated to selling all of their knockoffs of our plush, for example. That’s definitely a situation where we have to issue takedowns and the like.”

“We launched a teaser for a Banjo-Kazooie plush where [the image showed] just the silhouette of the characters, and those darkened silhouettes got ripped off and made as T-shirts,” Lane said, laughing. “It’s just ridiculous. People are combing through and finding anything they can to make a bootleg.”

“The thing is, we started as a fan-operated, fan art company, and we’re not trying to squash anybody who’s doing that,” Young continued. “But anybody who sees any amount of success, and makes a career and a living off of this, we hope they’re pursuing official licensing as well, because that’s the right thing to do. If you’re making merchandise for a game somebody else made, that should be at the top of your mind: How do I make sure the people who are responsible for this are benefitting somehow?”

Since 2016, with the help of relatively new hire Lane, Fangamer’s products have become “90, maybe 99 percent official” by Young’s estimate. Despite this transformation, however, there are still a handful of unlicensed designs that the site still sells today. Note that all three of those linked designs have one thing in common: They’re inspired by Nintendo games. To this day, the company has yet to sign a deal with Fangamer; Lane describes it as the site’s “white whale.”

While these unlicensed shirts have continued to sell, the real reason they’ve stuck around is that Young can’t bear to remove them from the site. “Look, it’s just our core,” he says. “That’s where we came from. When we made them, we felt pretty strongly that the way we approached it was fair, legal, and ethical, and I still feel that way. There’s never been pressure from Nintendo to stop selling this Earthbound merchandise because there is no competition.”

“Until this article gets published,” Lane added, the pair laughing.

Ever since Undertale parted the seas, droves of indie developers have shot off fusillades of emails in Fangamer’s direction, hoping to get shirts emblazoned with tokens of their game onto the storefront. But while the merchandise that the company creates can form a sizable chunk of a successful game’s revenue, Young says that some developers are starting to see a partnership with Fangamer as a badge of pride, a symbol of “making it” in the highly competitive indie market, which Young feels deeply conflicted about. As he sees it, while a game’s overall quality and its ability to move product are definitely correlated, a hit game is no guarantee of a successful run of merchandise—even in the massive triple-A space.

“Sales absolutely matter, for sure, but it also depends on a lot of different factors,” he said. “One thing we’ve found is that when people really emotionally connect to characters, they’re way more likely to buy a shirt. There’s at least one game where we’ve put out a shirt or two, and they haven’t sold, but we’ve made a bunch of different weird things that did. A great puzzle game might play well, but it’s probably not going to drive merchandise. It all really depends… Saying no is always hard, because the people we’re talking with are always very passionate about their games, and eager to work with us. The thing is, we have to print at least 110 shirts for every run, and if that doesn’t make sense, then we have to really reconsider our approach.”

Since the heady days of the mid-2010s, Young has instituted a blanket policy to help bolster the growing company: Fangamer will no longer agree to make products for games that haven’t come out yet. While he admits the site has made some exceptions since, he says that such agreements are typically “terrible business decisions,” even when they work out. For the most part, even today, Young and Lane say that the deals they end up striking are often borne more out of the staff’s collective passion for the property, such as the mostly-forgotten N64 cult racer Snowboard Kids, rather than cold, hard dollars and cents.

But Young wouldn’t have it any other way. “I know this might sound a little strange, but we never went into this with the profit motive square in our minds. We wanted to make a living, sure, and we wanted to make merchandise for the games we love. Seeing that we have 40 to 50 employees now, that’s a lot of livelihoods, and we’re supporting the game creators, too. A lot of creators come to us almost out of necessity, because they might make merch on their own and determine, ‘Whoa, it’s very difficult to produce, sell, and ship all this merch when I also need to make a game.’

“If we can make their lives easier, then it’s all worth it.”

Header image and product images courtesy of Fangamer

Steven T. Wright is a reporter and novelist living in the Twin Cities. He is the former independent games columnist for Variety, and he has written for Rolling Stone, Polygon, Vice, and many others. He almost named his novel after a city in Final Fantasy, but his friends talked him out of it.