“I have nothing to do with video games,” Junji Ito told the crowd at his first North American panel earlier this year.

A reasonable observer might disagree. Even if the renowned manga artist isn’t keeping tabs himself, the body of work Ito has created in his native Japan over the past three decades has given him an outsized influence on the horror genre, an influence that extends into gaming. Beyond obvious homages like the upcoming one-bit RPG World of Horror—which gleefully cribs the tone and visual style from Ito’s manga—anyone familiar with his work has no doubt seen its shadow in a wide selection of horror games.

Ito’s panel, conducted with the help of manga historian and publisher Ryan Sands, was full of illuminating tidbits. The artist confessed that his biggest fears are the environment, cockroaches, and beautiful people. (Very relatable.) When presented with examples of how shows like Spongebob Squarepants and Steven Universe have casually referenced his gruesome illustrations, Ito expressed disbelief that such cartoons existed.

But the conversation was perhaps most notable because it brought some closure to a chapter of Ito’s career that never came to pass, one that would have seen his most direct involvement yet with the gaming world. About 40 minutes into the session, Sands brought up “another project” that elicited a stew of cheers, groans, and sighs from the crowd. A screen to the right of the two men flipped from a shot of some of Ito’s signature ghouls (gaunt human heads floating away, necks stretched and fraying like tomato paste in the bubbling stew) to something more terrifying: the logo of the ill-fated Silent Hills.

Credit: Konami

Silent Hills is a ghost that haunts video games. The victim of a falling out between Konami and its star talent, Hideo Kojima. The canceled project lives on only through a single trailer and a now-unpublished proof of concept demo, P.T. Some elements may have made their way into Kojima’s Death Stranding—at the very least, that game inherited Silent Hills’ planned leading man, Norman Reedus—but the original vision for the project looks to be lost to everyone who didn’t work on it.

Ito was to have been one of those collaborators, joining Kojima, Reedus, and the soon-to-be-Academy-Award-winning director Guillermo del Toro. The artist’s involvement didn’t become public until months after the cancellation, when del Toro broke the news via Twitter.

By Ito’s own description of events, he and Kojima had a fancy dinner, joined del Toro for a night of karaoke, and the trio gassed one another up on the thought of making something together. He sat quietly in on one meeting at Konami. The game he described del Toro pitching sounds a lot like P.T. Ito said he’d has never played a Silent Hill game and still doesn’t know what the series is about. In fact, he doesn’t play games at all: “I’m worried that if I get into video games I’ll skip out on work.”

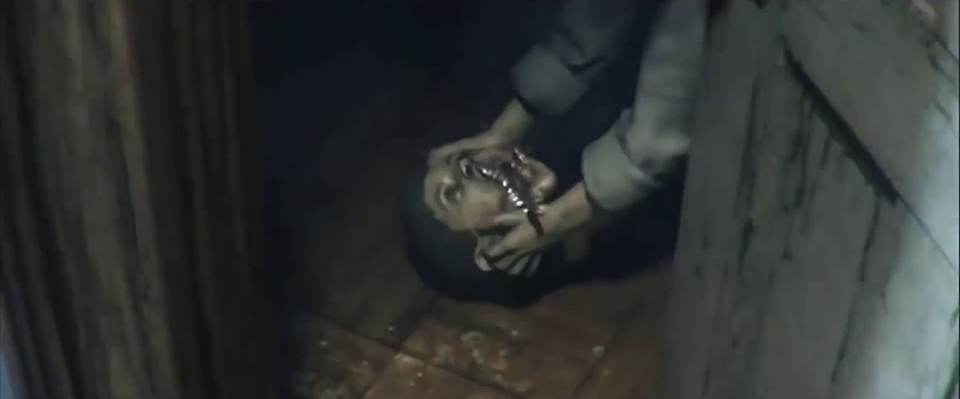

When Ito said he never put a pencil to page for Silent Hills, you could hear gasps from the crowd. The one surviving cinematic trailer from 2014 made it look like the artist had already got his hundred spindly fingers all over it. A homunculus pulling itself through a grimy residential hallway. Centipedes boring holes from human heads and the walls alike, as if states of matter were different only in concept. Even though Ito hadn’t yet been involved creatively, Kojima and del Toro were certainly setting the scene for him to arrive.

Credit: Konami

If Silent Hills is the ghost that haunts video games, Junji Ito is a phantom that haunts everything.

In the early ’90s, Ito was still a practicing dental technician, submitting short stories to magazines on the side. His Tomie series, a collection of grisly tales centered around a mysterious and hypnotic woman, ran in Monthly Halloween magazine starting in 1987. By the late ’90s, Ito had left his day job and was shaping up to be an icon. He released his popular Uzumaki series, a story about the horrific repercussions of spirals, and saw a steady stream of films and shows adapted from his works. Adult Swim will release its own adaptation of Uzumaki next year.

At the turn of the century, everything in North America was shaping up in Ito’s favor. Japanese entertainment became mainstream as networks like Cartoon Network and YTV blasted shows like Gundam Wing, Dragon Ball and Trigun. Even Japanese psychological horror became vogue thanks to Silent Hill and The Ring.

Credit: Niccolò Caranti (CC BY-SA 4.0)

On the primordial internet, Ito’s work had a certain edge. Since his stories were finite in length—unlike the many ongoing manga series that required knowledge of a vast back catalog and an ongoing commitment—they were easy to spread online, campfire lore for the young web. Individual stories, pages or even panels were enough to stop a scroll wheel in its tracks. Images from Uzumaki—faces and places twisting into themselves into atom-sized blackholes—or the infamous Amigara Fault—a tale of people being compelled to wriggle themselves into holes on a rockface—were worth 1,000 haunting words. Offering a longer-lasting unease than ye olde jumpscare Flash pages, you felt compelled to share them with others. They were too disturbing not to. Ito’s work is memetic, the internet’s most favored quality.

Ito didn’t emerge from the void. Genre is naturally iterative, and Ito’s work sprung up within a terroir of H.P. Lovecraft, Mary Shelly, Stephen King, and Kazuo Umezu (himself an early supporter of Ito’s work). The worlds Ito creates are full of horrible creatures, but what really dooms his characters are their obsessions. Nudges of the mind that end up shredding the body apart. Men and women so infatuated by a woman named Tomie they mutate. Suckers so curious about a tree sap that they’ll risk being flattened by a god. Unending impulses on these unlucky subjects to become something horrible, grotesque and new.

Ito exhibits an uncanny knack in his drawings for visualizing dysmorphia, the feeling that the body, its skin, bones, muscles are staging a coup. That the human form is untrustworthy and only funhouse mirrors can be trusted. This, in particular, is what makes him memetic—these emotive, guttural, shareable horrors. Not unlike how the Victorian crisis of faith spawned Frankenstein and the late-’60s paperback boom led the way for Carrie, the rise of the internet and digital media set up Junji Ito to become the century’s vision for horror.

Silent Hills isn’t the first game to look like Junji Ito worked on it. It’s just the first video game where that would have been the case. Slenderman, the internet’s closet monster, demonic meme and occasional video game star, is as gaunt, towering and strewn as Ito’s monsters. I think of his 2003 The Woman Next Door, with its tall, stickly stalker whose true face brands the iris.

The same way Lovecraft and Umezu fed the mind of Junji Ito, Ito feeds the world of new creators. Creepypasta chillers like Slenderman and mysterious staircases seem to borrow heavily from Ito’s work. Dark things that begin as urban legends before they haunt the mind, threaten the physical, and compel users unknown to post online warnings to start the cycle anew. It’s all part of a food chain of nightmares, Ito feeding into the web’s imagination, and the new beasts echoing into new media. Just look at the creepypasta-style stories at the heart of Remedy’s newest hit, Control. And you can find particles of the phenomenon in everything from Silent Hill 4 to Dead Space to Doki Doki Literature Club, works that feel spiritually, if not directly or intentionally, descended from Ito’s work.

This thrumming is even louder in indie games—and louder nowhere than in the RPG World of Horror. Paweł Koźmiński, the game’s creator, shares with Ito a background as a dental worker. Makes you wonder what horrible, corrupting visions are lurking in the depths of the human mouth.

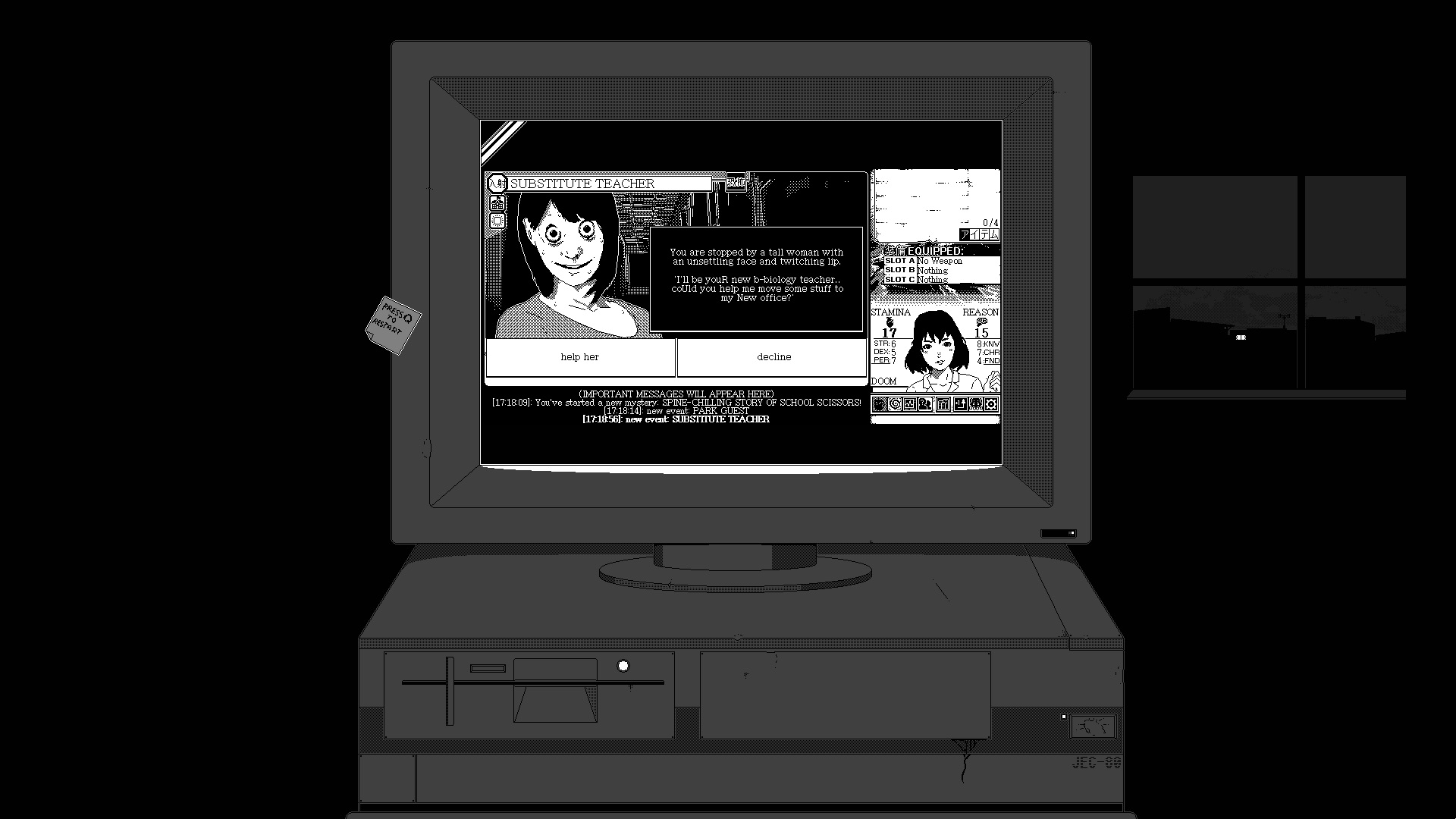

World of Horror bears some resemblance to a number of classic nightmares for Japan’s PC-8800 computer, adventure games with fraying pixels, surgical color palettes, weighty moods and the ever-present dread that the next static screen will be the last one you see. But it’s World of Horror’s Ito influences that run deepest and loom largest.

Credit: Paweł Koźmiński

The game places you in a small Japanese seaside town beset by cosmic plagues. In a series of episodes, you have to navigate through haunted hospitals, residences, and schoolhouses, surrounded by ghouls and weirdos under the influence of an unravelling reality. To dispose of them, you’ll have to research rituals and gather odd objects. You can choose to—or be forced to—engage in turn-based combat. You can attempt to lash back or dedicate action slots to scan your environment for alternative solutions. In the current demo build, you sneak around a school hallway following the disappearance of a student. There are tall tales of an eerie, smiling scissor-slinger, but she’s not the only creature acting as a hall monitor.

Like so many, Koźmiński first encountered Junji Ito in an online fan translation and found himself haunted by one of the story’s panels. The effect seems to have lingered. Even in the demo there are layers and layers of nods to the work of Ito, as well as of Lovecraft and Umezu. In an attempt to replicate the unnerving graphical style of the PC-88 games, Koźmiński decided limit himself to MS-Paint, an aesthetic similar to the manga-influenced Russian artist Uno Moralez.

World of Horror features an option to maximize the window to simulate playing the game in a pitch-black room with nothing illuminated other than the CRT monitor and a single window across the street. If you are like me, and the last thing to make you bolt out of your seat in a game was catching your own reflection in Her Story, then this is the obvious way to go.

During the panel, Ito told Sands that he wouldn’t mind “another chance” at making a game. (In another interview, he expressed an interest in virtual reality and, while laughing, workshopped a concept for a VR game based on one of his stories that would (gently) strangle players when they failed.) But mostly, the artist doesn’t think he has the time to invest in the video game industry. He said balancing work and leisure are important to him, and that Astro Boy creator Osamu Tezuka could have lived past 60 if he took more time off.

Lucky for Ito, he doesn’t have to put in any extra effort for games to be made out of his work. It’s already happening. His visceral creations and the timing of his ascent have made him, like many monster makers before him, an inseparable part of horror culture and video game DNA.

The blood is in the water now. The nightmares like the taste of it.

There’s no escaping Junji Ito.

Header image credit: World of Horror, Paweł Koźmiński

Zack Kotzer is a former carny and current writer out of Toronto. His work has been published in The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, Motherboard, Polygon, Kill Screen, and a column in NOW Magazine. His first book, Keeping the Ball Alive, details the history of the only pinball factory to survive the ’90s. He collects Fido Dido merch.