This article contains spoilers for the Yakuza series.

For a series known for its larger-than-life displays of machismo, Yakuza 5 changed things up by introducing the series’ first playable female protagonist. However, rather than introduce an entirely new character, like the previous entry had with Shun Akiyma or Taiga Saejima, it was a long overdue gameplay debut for one of its central characters, Haruka Sawamura. Just as players will have spent the best part of a decade growing old with Kazuma Kiryu, they have also been following a young girl growing up into her teens, and eventually to adulthood and motherhood by the end of the series.

To have that kind of arc is rare when stories are usually taken up by big masculine egos. That’s not surprising when considering the series was conceived with an exclusively Japanese adult male demographic in mind. With that came a traditional representation of a gritty criminal underworld where men talk money, politics, and honor, but talk even louder with their fists, while women exist as either victims to be rescued or avenged. More often than not they’re just eye-candy operating in Tokyo’s fictional red-light district of Kamurocho—it’s especially telling that the only real-life women whose likenesses used in the games up to this point have been gravure models and adult actresses.

Haruka stands out from the moment Kiryu first encounters her in the original Yakuza, which would be the case with any nine year-old child by herself in the very adult Kamurocho, let alone one clutching a gun in the aftermath of a bloody shooting. Given her circumstances, Haruka’s had to grow up fast, often displaying a mature and headstrong disposition beyond her years. She is nonetheless a dependent, someone Kiryu has to protect on a number of occasions but she also forgoes much of her childhood, assuming a maternal role as a preteen when she helps run the Morning Glory Orphanage in Yakuza 3. One might assume that Haruka wants for nothing, happy to be a rock for her adoptive family.

But Haruka does have a dream, one that players could have picked up on if they, as Kiryu, had spent any time taking her to karaoke bars during downtime in previous games. So it is in Yakuza 5 that she has the opportunity to pursue a dream shared by many a Japanese teenage girl: pop stardom.

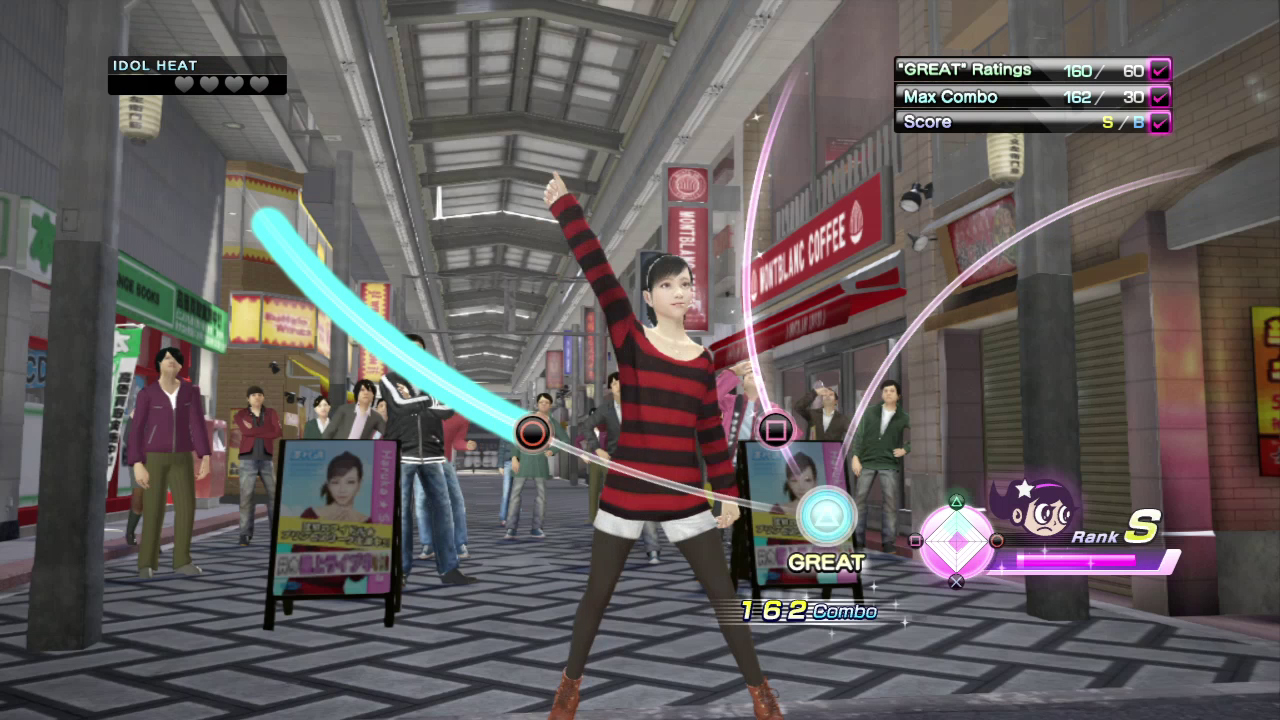

As she learns to sing and dance her way to number one in the Princess League J-pop idol tournament, Haruka picks up the baton from female icons of the rhythm-action genre like Space Channel 5’s Ulala and vocaloid Hatsune Miku, whose Project Diva series is also developed by Sega.

Yet her presence in the five-character roster, the largest the series has had to date, cuts a stark contrast to the yakuza politicking, turf wars, and murder conspiracies Kiryu and his peers embroil themselves in. It would be easy to dismiss Haruka’s segment as a bit of light filler in between the high-stakes drama. That, fortunately, isn’t the case—in many ways, having Haruka as a playable character is arguably the game’s highlight.

Haruka’s gameplay segments offer a refreshing break from the usual macho brawling, because even though multiple protagonists allow for different fighting styles, once the novelty of an insane bone-crunching Heat Action has worn off, the combat in Yakuza is often its most tedious aspect. It’s for a similar good reason that the most fun you have with Kiryu in Yakuza 5 is when he’s taking on side missions as a taxi driver who actually has to abide by the driver’s manual.

Credit: Sega

Although Haruka’s story doesn’t play out in Kamurocho, Osaka’s Sotenbori is familiar territory, previously seen in Yakuza 2 but explored in a different context in Yakuza 5. Instead of being jumped by random thugs for a beatdown, Haruka can approach a number of characters around town for dance battles. Of course, running into other teenage girls for a wholesome street dance-off is far-fetched, but then so are the odds of being physically assaulted in one of the safest cities in the world (the real-life Dotonbori in Osaka is also far more crowded).

You could still call dance battles “fights” since they are determined by the character’s health meter. The goal is to maintain a good rhythm to the music, as each successful button tap inches a timebomb along a gauge in the middle of the screen so that it detonates on your opponent’s side, knocking down their health and tiring them out.

The series’ signature Heat Techniques also feature as part of Haruka’s repertoire. The twist is that the buttons that are usually used for triggering flashy violent maneuvers like slamming someone’s face into a wall or smashing a bicycle over their head instead let Haruka strike a cutesy pose that either recharges her energy or stuns her opponent into exhaustion. In the case of the big stage Princess League showdowns, it even calls for dramatic costume changes.

Yet to characterize Haruka’s arc as frivolous fantasy out of place with the rest of the game’s dark and serious tone would be misleading, as if the series doesn’t indulge in flights of fancy with the rest of its cast. Her path to becoming an idol comes at great cost: Kiryu purposefully distances himself from her and the orphanage so as to not tarnish her image, and her agency’s president, Mirei Park, is murdered.

More grounded, however, are the day-to-day conflicts and pressures Haruka faces as an emerging idol. Her unpleasant encounters with the idol duo T-Set may follow the cliché of a bitchy rivalry, but for a teenage girl, the cruelty of what other teenage girls can do or say can seem tougher to overcome than standing up to yakuza thugs. Unlike the other male protagonists, Haruka doesn’t have the privilege of just punching away her problems.

Credit: Sega

When Haruka’s not singing and dancing, she’s also taking on other jobs to build up her profile. Like many of Yakuza 5’s other side quests, they can be playful and a touch strange (the “Running Girl” show she takes part in is largely unexplained) but they also depict the hurdles a pop idol goes through in believable ways.

One of Haruka’s first jobs is a handshake event, a meet-and-greet that’s part and parcel of an idol’s role. In the game, these events are presented quite modestly as promotion for a local business, though in real-life, you usually can’t attend these events without a ticket, which is only issued after buying the artist’s CD or product beforehand. The comical thing is that all of the fans lining up for Haruka’s events are grown adult men, mostly of the nerdy and socially inept variety. While some are happy just to wish her well, there are also plenty of creepy responses: commenting on Haruka’s appearance and marriage proposals.

It’s not enough to stay silent, nor can she shut them down, at least not if she intends to do a good job. Mechanically, it’s just a case of matching text colors to succeed, but the “correct” response comes down to being able to placate these men so that they don’t come away disappointed and knock down on your satisfaction rating. It’s a reality many women are all too familiar with, where unreciprocated advances from strangers can quickly turn to misogynistic insults.

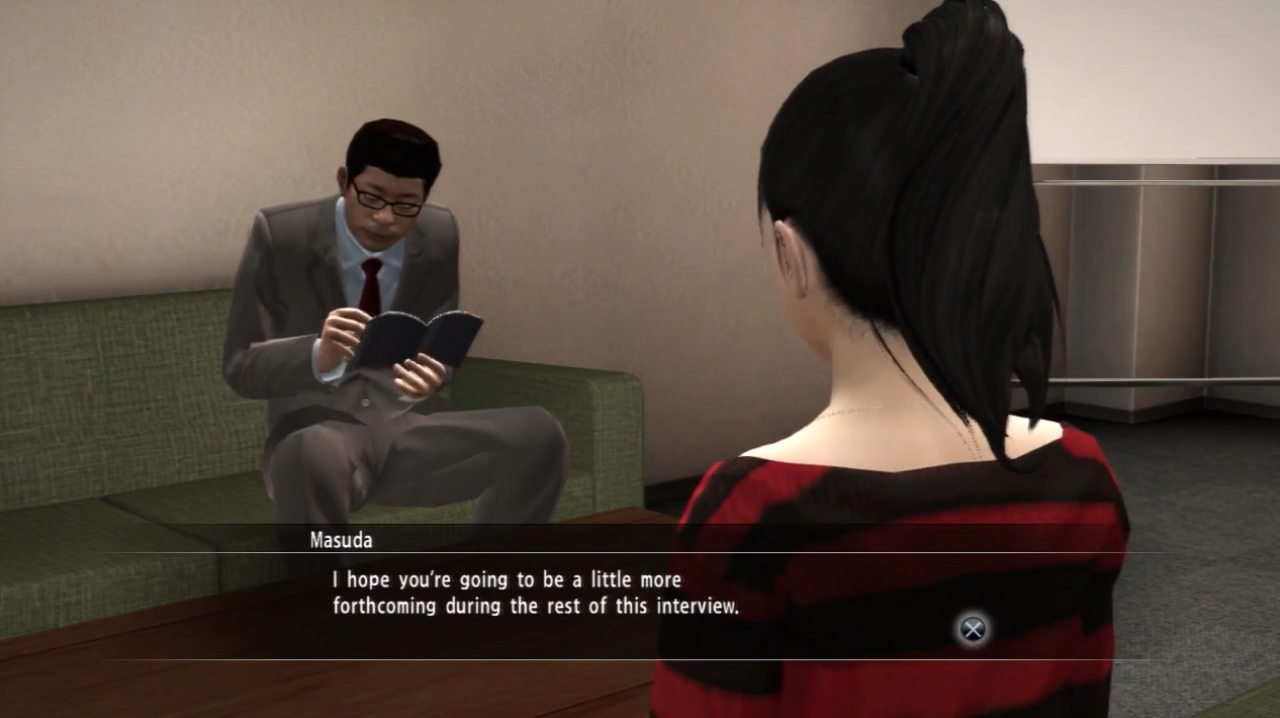

This societal balancing act is reflected in Haruka’s other jobs, from being a guest on a TV chat show where she might be subject to an inappropriate comment from the host to being interviewed by various publications targeting different audiences. In the latter, a journalist does his utmost to goad Haruka into badmouthing her rivals with the aim of causing a scandal for the gossip rags. Even if you’ve never had media training, going through these segments offers a glimpse into the exhausting standards expected of not just a pop idol but a young woman whose appearance, words, and actions are all fair game within a patriarchal society.

Credit: Sega

It’s questionable how much this can be viewed as an intentional critique on the developer’s part; the series, after all, continues to indulge in minigames premised on ogling women. But by putting you in the shoes of Haruka, someone you’ve known like a daughter all this time, the game asks its players to empathize with the casual sexism a young woman like her has to endure.

Since Yakuza 5’s initial release, there have been signs the series is moving beyond since its narrow original target audience. In a 2016 interview with Famitsu (translated by Siliconera), series creator Toshihiro Nagoshi revealed that there had been an increase in female players, up to 20 percent of the player base. While Nagoshi also claimed the team has been careful not to be too conscious of female users and derail from their vision, the series has since reached a wider and more diverse international audience of men and women alike.

In that time, we’ve also seen rereleases of the earlier games. Far from simply retelling the old stories with updated graphics, it’s been a chance to revise outdated elements—such as removing a transphobic side quest in Yakuza 3—while also comfortably poking fun at Yakuza’s own chiseled masculinity. New side quests in the “Kiwami” remakes see fan-favorite Goro Majima dragging it up as a cabaret hostess while Kiryu unwittingly takes jobs striking topless kawaii poses for a shady photographer and voice-acting for a yaoi (boy’s love) video game.

Credit: Sega

As the latest, Yakuza: Like A Dragon, once again shakes up the series, with a new location, a new protagonist and also a drastic change to a turn-based RPG, it also includes a playable female character in the party. In hindsight, whether or not Nagoshi’s team intended it, one teenage girl’s brief spell in the spotlight marked not only a turning point for the series in the West but also its expectations of gender and what place a woman can have in its world. Haruka’s dream has been anything but an anomaly.

Header image credit: Sega

Alan Wen is a full-time freelance game critic who has written for Eurogamer, Kotaku UK, Wireframe and more. His main interests lie in Japanese games and culture. When he’s not spending too much time on JRPGs, he’s wasting it on Twitter @DaMisanthrope.