Internet grammar is Good. “It’s hard to convey meaning over text!!!” people complain, which is true, but in the last decade or so we’ve been getting soooo much better at it. People who are chronically Online know what it means when I capitalize the first letter of that word, or when i don’t capitalize that pronoun referring to myself. They might not be able to express it; it’s more of a feeling. Over time we’ve developed ways to get across nuance, emulating what would otherwise be conveyed by our tone of voice and body language. Mostly we do it by breaking—and then rewriting—the rules.

Last year, Gretchen McCulloch published her book Because Internet: Understanding How Language is Changing. “We write all the time now,” she points out, “and most of what we’re writing is informal. [There is] a vast sea of unedited, unfiltered words that once might have only been spoken.”

Not only has this constant use of informal written language meant we need ways to inject tone into text, it’s allowed for it by opening up who’s writing and why. Grammar is no longer prescribed by books and formal articles, McCulloch argues. It’s created by all of us. “There is space for innovation… space for linguistic playfulness and creativity.”

It’s no surprise this playfulness has found its way into games. In particular, many games are set on the internet itself. The player navigates interfaces designed in the style of webpages or instant messaging chats, usually from an earlier point in internet history. How we communicate online has never remained static, so by writing the games how we used to write then, they can showcase their setting and—for those who remember it—trigger a flood of nostalgia.

Credit: No More Robots, Tendershoot, Michael Lasch, ThatWhichIs Media

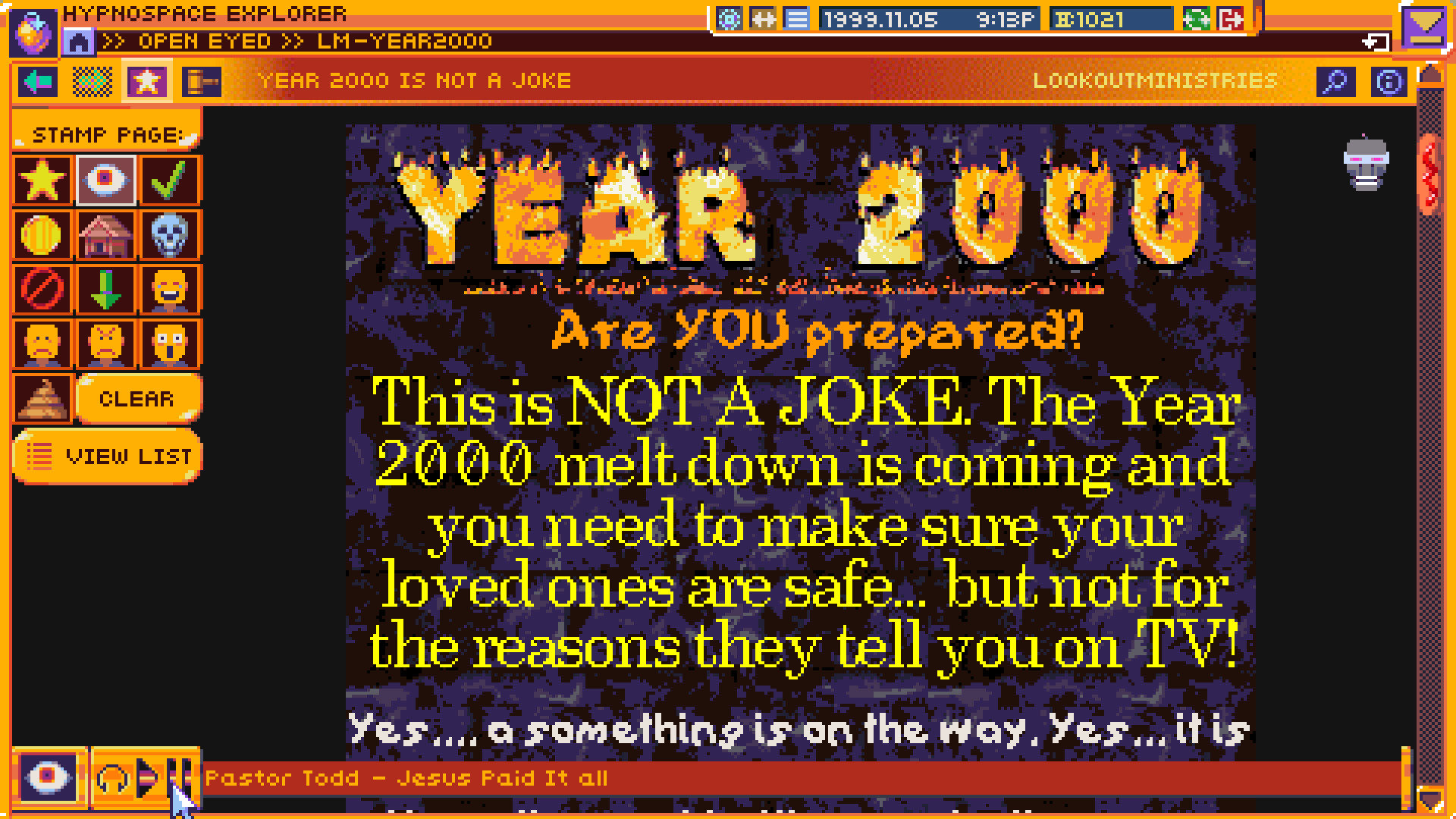

Take Hypnospace Outlaw, a game set in 1999. The player is put in the role of a content moderator tasked with patrolling GeoCities-style pages created by other characters, soaking in the aesthetic of the era as they go. Bringing in 2020s Twitter talk would throw off the entire magic of stepping through a portal to the early internet. It’s cluttered with bright images, spinning gifs, and autoplay music, but the language is mostly formal. The exceptions are, themselves, dated. “c00l!” is precisely the kind of leetspeak that is no longer cool.

Hypnospace’s characters, the ones creating their online pages, are also often older. You can tell not just by their interests and their propensity to fall for scams and viruses, but by how they type. Pay attention to their choice of punctuation-based smileys (of course, emoji weren’t widespread in 1999), particularly the fact that they have noses: :-).

Credit: Kyle Seeley

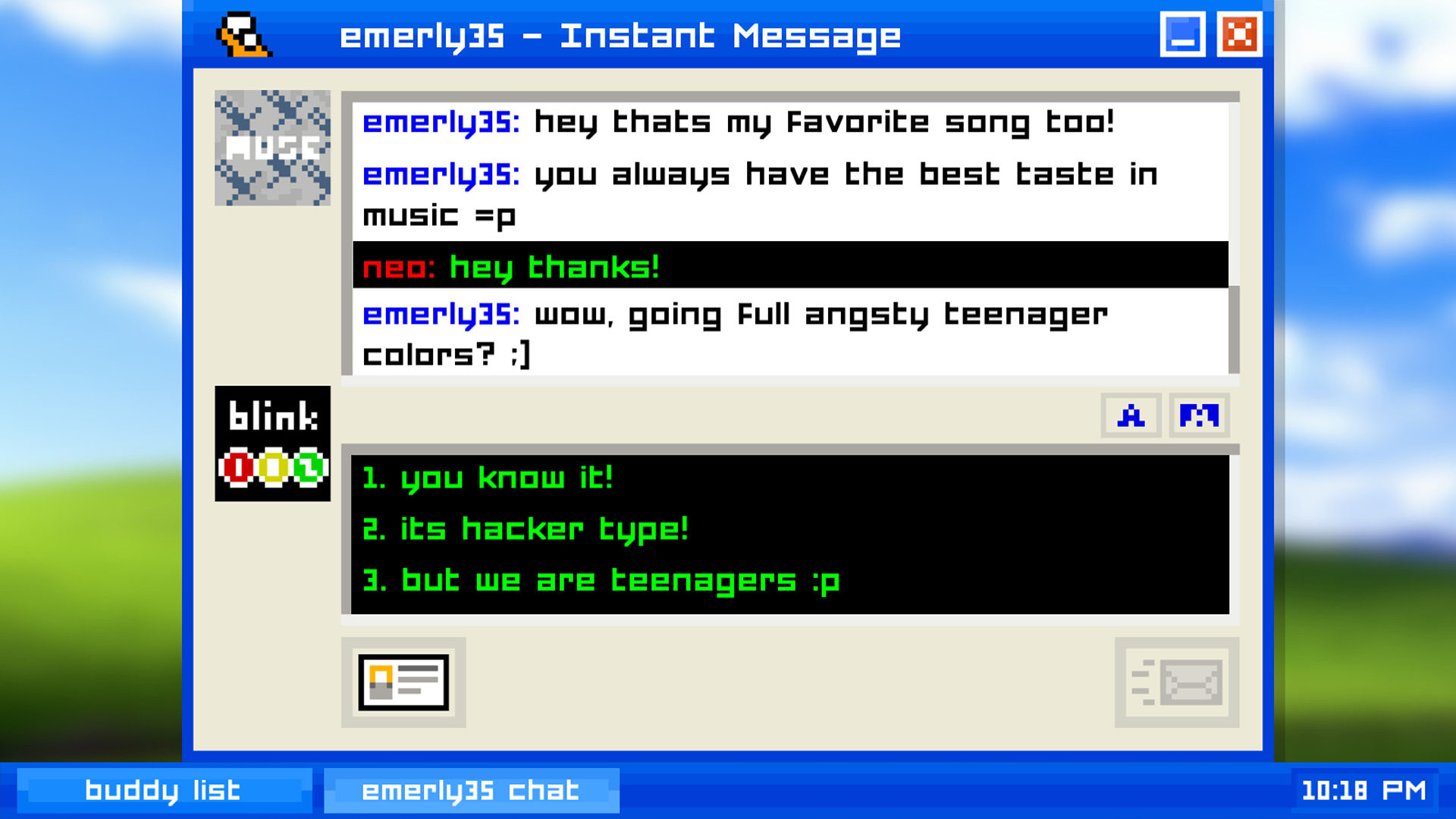

Set only a couple of years after the era of Hypnospace Outlaw, Emily is Away trades in websites for instant messengers—one-on-one communication rather than outward-facing webpages. Suddenly, we see smileys with no noses. The game’s characters are also prone to use more than just the straightforward colon eyes and close bracket mouth, like the teasing =P. Internet grammar changes fast, and moreover, these are teen girls typing. Teen girls are always at the forefront of lingual change, especially online. In the same vein, you’ll barely see a capital letter in their dashed off back and forths. No one wants to be insufferably formal on AIM.

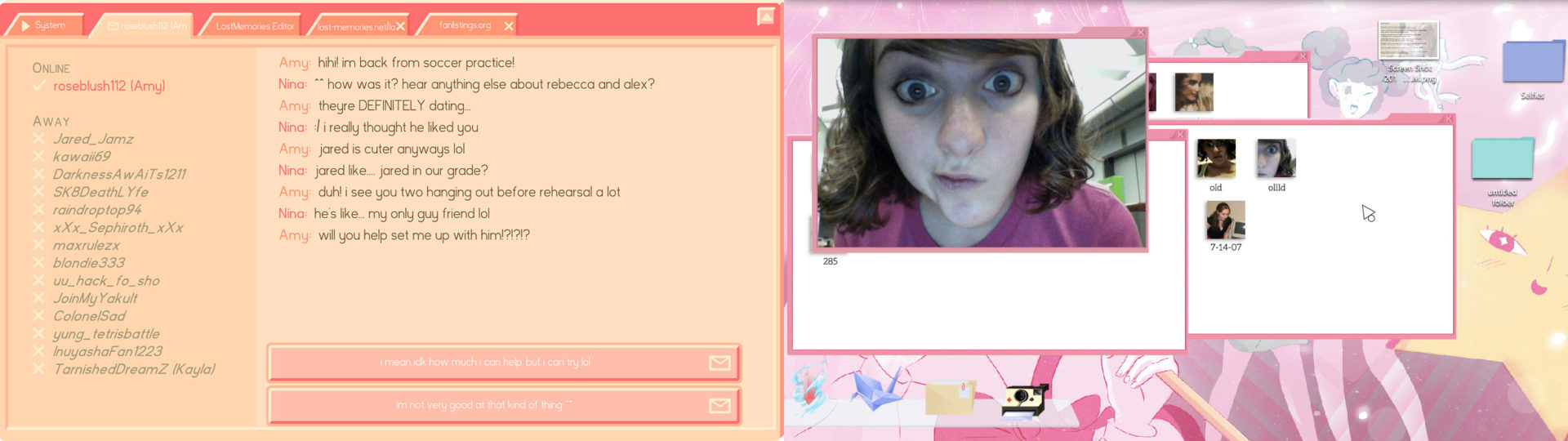

McCulloch herself cites teen blog simulator Lost Memories Dot Net as a potential “wave of nostalgia.” Lost Memories writer Nina Freeman also worked on the semi-autobiographical love story Cibele, which at times layers up so many bits of internet grammar that it takes time to pick them apart. “hihi! are you going to the bulldog hell release tonight? i don’t wanna go alone haha” reads one message from Nina’s friend. “BTW aren’t you turning 19 in like a few weeks? WHEN ARE WE PLANNING THE PARTY???”

A lot of this wouldn’t feel out of place among millenials and zoomers online today. The variation from no capitals when expressing vulnerability about not wanting to go to a show alone to all-caps and repeated punctuation when overenthusiastically shouting about Nina’s birthday party is a classic. (Capital letters as shouting are a more recent phenomenon than they seem: Though they were sometimes used in earlier books, it only became common code in the early bulletin board internet of the 1980s. Which is why your grandma doesn’t know she’s yelling every time she emails in uppercase.)

Credit: Nina Freeman, Aaron Freedman, Star Maid Games

But there are still hints that this line in Cibele is from an earlier internet. McCulloch writes that “BTW” was one of the earliest online initialisms that’s still in use, dating all the way back to 1977. But nowadays we rarely have to signal that it’s a collapsed phrase by shifting it into capitals. If you don’t believe me, stick it into the Twitter search bar. It’s usually all lower case, unless the person is already SHOUTING.

An average player probably wouldn’t spend time breaking down all the different grammatical tricks in Cibele’s throwaway messages. But thanks to our familiarity with internet subtext, this kind of writing can give an instinctive recognition of time and place, while also showing differences between characters. Her male friends, for example, tend to write with less flair, seeming reserved about coming across as overly enthusiastic or feminine. These are things we pick up on instinctively as Internet People, the same way we don’t have to think too much about tone of voice or body language.

This works even if the games aren’t actually trying to evoke the lives of teens online. Many indie games can’t afford or don’t want to include voice acting, so despite being dialogue driven, they have to get across speech in text. And given that’s the catalyst for how new internet grammar emerges, it makes sense that we’re beginning to find games using these tricks to express themselves and their characters.

For some, it’s just to create the right tone. Exclamation marks in email are the easiest way to make more formal online communication not seem mean, which is why people scatter them everywhere. The same can be applied to Wandersong, the bounciest, most optimistic game of 2018. Though it doesn’t go all the way into teen text speak, it also leans on tricks like SHOUTY CAPS and loooooooong words to properly express its casual cheer. But these quirks aren’t evenly applied; the ever-happy protagonist Bard gets dozens, where his more reserved witch companion Miriam might only use them in frustration.

Credit: Greg Lobanov

This application of internet grammar to create both mood and characterization can also be seen in Night in the Woods. Though it has some online communication between its characters that fall more closely to Emily is Away or Cibele’s use, they also spill out beyond the confines of its in-game computer. “No! No no no no no no no no noooooooooo! Pastabilities is gone!!!” says Mae at one point. The approach cements the world as one full of ordinary millennials even as it veers into the supernatural, while demonstrating Mae’s youth and occasional childish flair for the dramatic.

But when it comes to internet grammaras characterization, you can’t do better than EXTREME MEATPUNKS FOREVER. Even the capitalization of the name should give away developer Heather Flowers’ willingness to change the rules, and just how it can be used for best effect. MEATPUNKS is a game about survival and defiance at all costs; its characters spend most of their time dragging themselves through a desert and fighting off fascists. Its capital letters are well earned.

But it’s MEATPUNKS’ heroes who best showcase the game’s attention to grammatical detail. Everyone speaks differently in real life, so it’s no surprise that we have our own idiolects online, too. Flowers is the best I’ve seen at using these to make her characters’ speech distinct from one another in a game without voice acting.

Take Cass, the de facto leader of the group. They don’t use capital letters or punctuation. They’re tired, and you can tell. You can imagine the way they’d speak if you could hear it; not monotone but something approaching it.

Sam, on the other hand, mostly speaks in complete, technically correct sentences. But he’s introduced across from Jason, who is both drunk and less reserved. “ur my best friend in the whole world!!!!” he says at one point, “but you dont gotta save me!!” Jason doesn’t appear again, but he’s used to set up Sam as someone who keeps his cards close to his chest, and the contrast in how the pair speak is part of that. Unlike Jason, Sam doesn’t put across his personality in how his speech is written, because he wouldn’t want to show that much of himself.

And then there’s Brad. “i’m brad, he/him, and i never fuckin learned how to read” he introduces himself, riffing off that one Vine. “what?” says Cass. “sorry sdkjflsdkf i couldn’t resist,” he replies.

Credit: Heather Flowers

How Brad keysmashes in what’s supposed to be spoken text isn’t important. What’s important is that Brad is an Internet Person. It tells us something about him immediately, and not just that he goes online too much. For instance, many of us wait to see how our texting partner writes and modulate to match; Brad would never do that. He speaks only like himself, because he knows what that is and is confident in it.

He approximates standard grammar only once, in an early scene, showing off his “call center voice” from a previous job. The juxtaposition demonstrates how important Brad’s voice is to his character, and how frustrating having to put on a veneer for customers must have been. It’s #relatable.

It also injects humanity and humor into MEATPUNKS, often at the same time. At one point, late in the game, he makes an impassioned speech about accepting that you can’t be 100 percent perfect all the time, and ends with “you know? :)” Sam, who had just embarrassed himself in front of him, just asks “how did you make that sound with your mouth?” It cuts through the tension, and you might think it’s breaking the fourth wall to remind you that Brad’s been speaking in a distinctly unspeakable way this whole time. But he explains that “somebody hacked my mouth for full ascii support.” It’s worldbuilding after all. And what a world MEATPUNKS has.

Through indie games, the flexibility and utility of internet grammar is being used for more than just social communication. Writers who are fluent in Online are able to apply their instinctive knowledge of how we express ourselves to reflect their games’ settings, tones, and worlds; show us who their characters are; and spin up plenty of nostalgia for the internet that went before.

Header image credit: Hypnospace Outlaw; No More Robots, Tendershoot, Michael Lasch, ThatWhichIs Media

Jay Castello is a freelance writer specialising in video games, falling down rabbit holes, and taking bad pictures of flowers.