Horror is a genre built on seeming contradictions. As entertainment, it seeks to attract and engage an audience, but it does so using sights, sounds, and emotions that are alienating, if not outright repulsive to us on a primal level. Being a horror fan means enjoying the adrenaline rush we get from confronting the dark, the depraved, the macabre, the dangerous—all the things our brains have evolved to avoid. It’s a genre that often uses the otherworldly and the implausible to convey striking truths about real human nature. It’s also a genre that manages to encompass both the most outré work from fringe creators and the biggest of big business. In 2017, horror films brought in a combined $733 million at the box office.

Horror’s most memorable successes span centuries and just about every form of pop culture, including literature, films, comics, and anime. But there’s one medium, to my mind, that captures horror in a way none of the others ever could: video games.

Fittingly enough, the two traits that make for great horror video games form a kind of paradox of their own. First, games have a unique ability to scare us because they make us participants in the story, immersing us in a setting we can explore and allowing us to influence how events unfold. But the best horror games also excel through the limitations they impose on the player, whether due to technology constraints or design intent, and often due to both. You’re in control, but hemmed in on all sides. You’re drawn into the world, but kept at a distance by its ever-present boundaries.

You’re terrified, but you can’t look away.

Credit: Konami

All games, in any genre, require your attention and involvement, and most modern titles attempt to convey a sense of presence in a believable world. But these qualities are particularly advantageous when it comes to imparting a sense of horror.

“Horror works often by establishing expectations and then breaking them, and this is potentially far more effective if we’re actually the person in the setting,” said RagnarRox, a YouTuber and video essayist who provides in-depth analyses of video game design. “In a game (if it’s well-crafted), you can never shout at the screen, ‘Oh look behind you!’ That’s ideally all up to you.”

This is, of course, a dramatic shift from horror films, which shock or scare the audience at a distance, agnostic to any reaction viewers may have. With games, however, the player must actively contribute to the story, at the bare minimum controlling the pace of their progress. They may still react outside the game the way they might during a horror film—jumping out of their chair or crying out in surprise—but they must also always consider their reaction within the game world.

If participation is vital to what makes horror games special, it’s immersion that helps to marry that sense of control to a place and a narrative that the player can become emotionally invested in. The same qualities that can make any sort of game immersive—high-fidelity graphics and polished presentation—can amplify the ability of horror titles to scare players, especially if they shut out the outside world.

“Horror and scaring oneself is a right of passage—a joy to be had with others—that can really be amped up by yourself in a darkened room with headphones on,” Julian Grant, a filmmaker, horror aficionado, and tenured associate professor at Columbia College Chicago. “Many times [while] playing a Resident Evil game or a title like Japan’s Fatal Frame series, I found myself looking over my shoulder to check that I was still alone.”

Another series Grant mentioned was EA’s Dead Space, sci-fi action-horror games that benefited from triple-A budgets and the technical knowledge of a major developer.

“For me, sound design is critical,” he said. “A good audio soundscape in horror adds so much. Dead Space really benefits from the sound design that is crucial for the immersive experience.”

For their time, the Dead Space games offered a gruesome level of graphical fidelity, as well. Grant highlighted the scene in Dead Space 2 where protagonist Isaac Clarke must use a machine to insert a needle into his eye, as the camera zooms in closer and closer to show everything in unnerving detail. “You feel like you need a shower afterwards,” he said.

Credit: EA

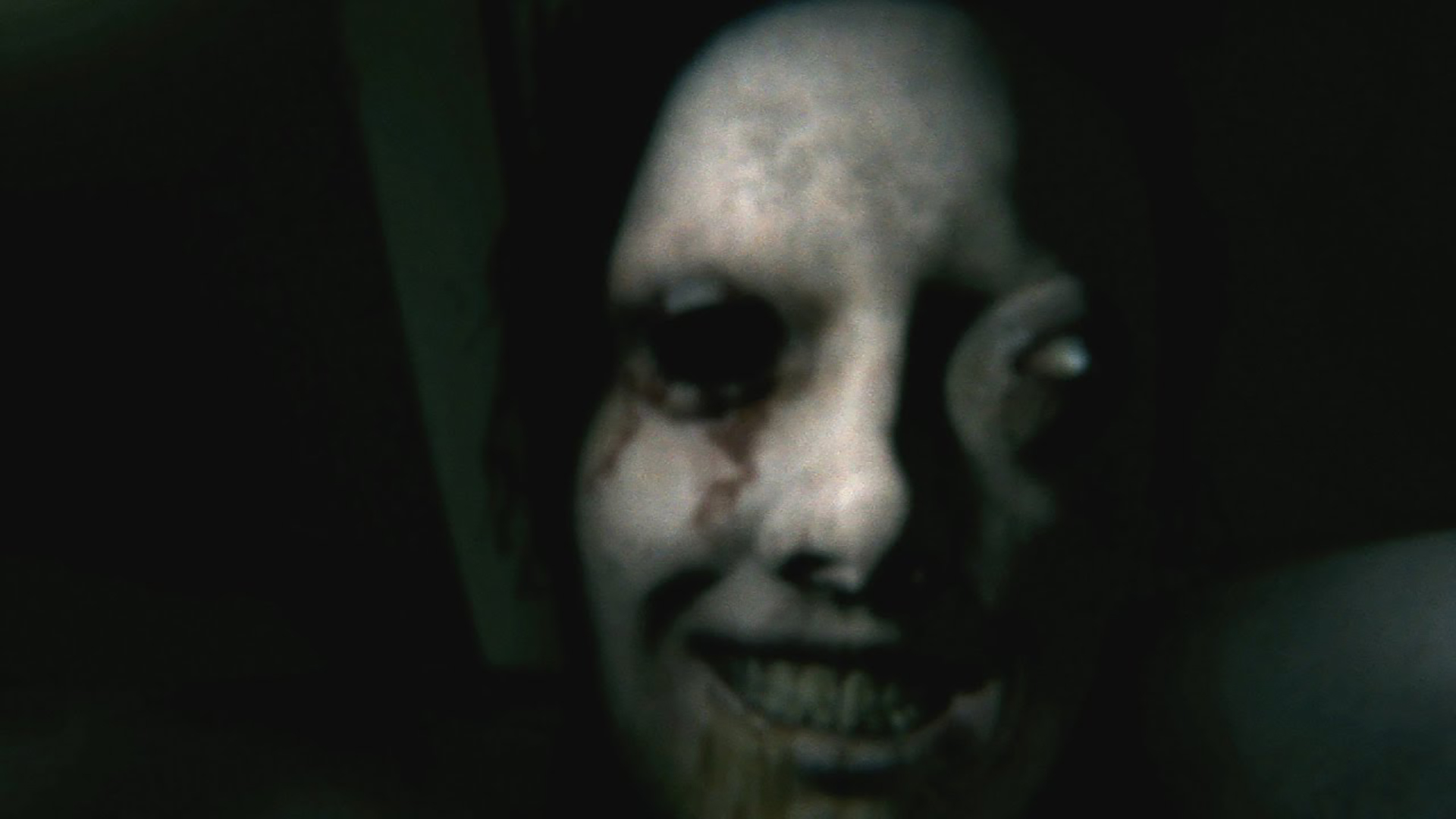

Though no longer available for the public to download, gaming’s most realistic-looking horror experience might be Hideo Kojima’s P.T., the playable teaser for the now-canceled Silent Hills. Small in scope but nearly photorealistic in its graphical style, the standalone demo sends players down the same corridors, over and over on a loop, stalked by a haunting figure. The verisimilitude of the environment mean that the small and large alterations to the environment—shifting objects and audio effects—are all the more unsettling.

Grant sees virtual reality as one way for future horror games to amplify the effect of this immersion, and he cited some early standouts. “Fully immersive VR horror titles like The Forest VR show how cool an open-world survival game can be. Wilson’s Heart on Oculus is full of guns, scares, and feels like a Silent Hill game. Of course, Resident Evil 7 VR is just chock full of great mutants, zombies, and scares,” he said. “I pulled the headset off a number of times.”

But if some level of participation and immersion are crucial to delivering a great horror game, they’re not on their own sufficient for capturing the spirit of the genre. So much of what makes horror effective comes from the sense of powerlessness and of the unknown. Just think about the best horror movies. During their most heightened moments, knowing you have no control over what will happen next adds to the tension, and a shadow can be more terrifying than a fully-realized monster. To capitalize on that side of the genre, games need to embrace certain limits to what they offer players.

While such limitations can come in many forms, that trait gives horror games a particularly fascinating relationship with technology. Deficiencies that might hurt a different kind of game can actually prove to be a boon when it comes to scaring players. Workarounds and shortcomings can become assets, whether intentionally or not.

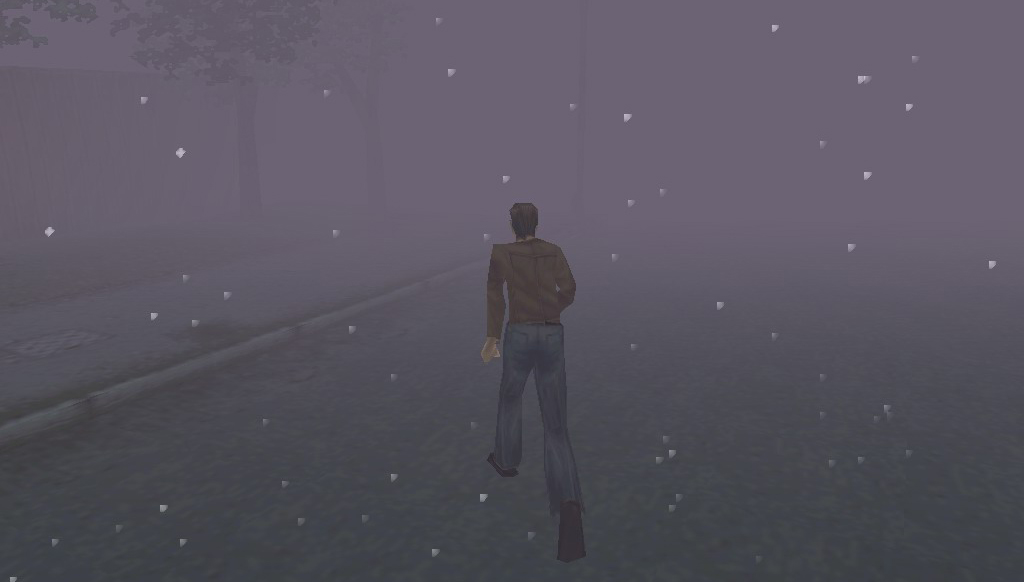

“I’m adamant that horror is a medium that thrives [on] limitations,” RagnarRox said. “Silent Hill’s iconic fog is probably the best example of this; the fog was an addition that came from the team desiring impressive graphics that were too heavy for the PSX to handle at the time, [given the developers] didn’t reduce the viewing distance radically.”

The graphical limitations ended up working in Silent Hill’s favor. Due to technical constraints, the player has a limited viewpoint throughout a large portion of the game. In turn, this creates a lot of anxiety, since the player doesn’t have a full understanding of where they are going.

Credit: Konami

Resident Evil was another game that leveraged its technical limitations into gameplay design in an effectively horrifying way. By using a fixed camera angle, what the player wants to see is usually just out of frame, creating a sense of mystery. They might not be able to see around the corner, but they can hear a zombie just out of sight.

“The technical evolution of gaming hardware has strongly benefited various genres out there, but horror is [one that has been] largely hindered by it,” RagnarRox said. “And you can still see that: Whenever a new horror game manages to break the mold, it is, in most cases, one that refrains from this desire to render everything in perfect detail. The mind has always been a much more effective canvas for horror than the monitor.”

It’s hard to argue against that sentiment. Perhaps the breakout horror title of the past decade, Frictional Games’ Amnesia: The Dark Descent, manages to elicit big scares with a far more limited scope than other games of the time. One of its most terrifying encounters is with a monster that’s never even rendered on screen.

Credit: Puppet Combo

Other indie developers have embraced limitations to great effect, as well. Indie developer Puppet Combo’s Babysitter Bloodbath and The Glass Staircase pay homage to old-school horror while also channeling gaming’s past. Notably, these games feature graphics reminiscent of the PlayStation era and incorporate limited, tank-style controls similar to the first Resident Evil. The stripped-down scheme creates an odd (and effective) dissonance between the player and the game. Nostalgia no doubt played a role in the design, but as an added effect it imparts a sense of discomfort, mirroring the tone of the rest of the experience.

There’s also September 1999, developed by 98DEMAKE, a horror-tinged walking simulator that lasts roughly 5 and a half minutes. Throughout that brief running time, the player controls a nameless protagonist from a first-person perspective, exploring a very limited space. The game starts out in a bedroom, eventually opening into a small hallway. After a set time, regardless of where the player stands, the screen will black out, the player finding themselves in a different space, time having moved forward. There’s very little in the way of narrative context, but when a body appears alongside large smears of blood, and the player sees flashing lights through the boarded up windows, the unease builds.

That games like September 1999 and Amnesia use the same first-person viewpoint that helps to increase immersion in VR horror games and other triple-A titles might seem odd at first, but the perspective can be seen as a kind of limitation, as well. While you may be getting a closer, more personal view of gruesome scenes, your field of view is more limited than with a third-person camera, leaving you with less knowledge of your surroundings and leaving you more vulnerable to threats from behind.

In fact, many first-person games lean into that sense of vulnerability by limiting what the player can accomplish. The Outlast games, for example, use the first-person perspective of a camcorder to pay homage to the cinematic genre of found-footage horror. Beyond the night vision the camera offers—even this limited by a battery meter—you have no physical abilities outside of running and hiding. As in Amnesia, you cannot fight back in any way.

Even more action-oriented horror games can still benefit from gameplay and design limitations. Take Dead Space, for example. The game may involve quite a bit more shooting than its early survival horror counterparts, but, at its core, it’s still the story of a regular person. You’re not a soldier. You aren’t someone with super strength. You’re an engineer.

Beyond that, the game shows terrific restraint in pacing out its setpieces. Sometimes the player will find themselves in combat with only a few foes, and sometimes they’ll go up against a mass of enemies. But they’ll also navigate long sequences with no threats and lots of atmospheric tension. The ship’s hallways echo with cracking sounds coming from pipes, random metallic clips and pops bouncing off one another. Steam hisses nearby, electronic devices beep and boop, and somewhere, in the distance, there’s a crawling sound. In this case, the atmospheric gloom feeds into suspense, feeding further into the anticipation of combat.

Credit: Nintendo

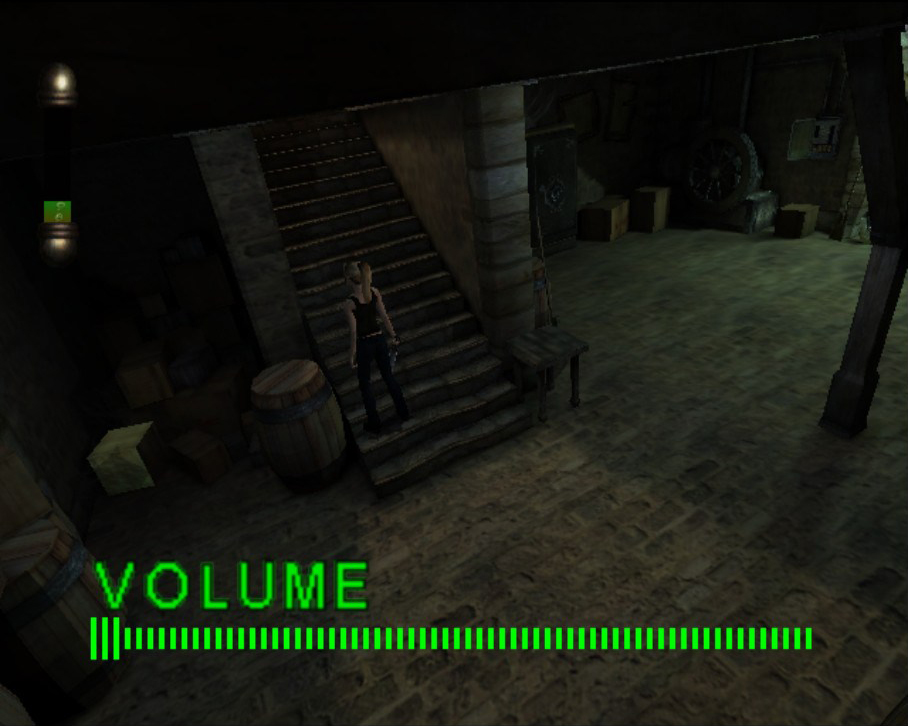

A unique approach to the concept of limitations can be found in the brilliant 2002 GameCube title Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem. As the player moves about the game, they need to be mindful of the on-screen “sanity meter.” If the bar gets too low, the game introduces some bizarre twists. Some resemble in-game bugs, but others go even further. In one instance, the volume will adjust itself with an onscreen meter designed to match the televisions of the era. In another, the game will pretend to crash, presenting a blue error screen. Here then, we have simulations of technological shortcomings, which simultaneously break the player’s immersion in the world of the game and extend the sense of horror beyond the fiction and into the real world.

Of course, embracing these qualities isn’t a guarantee that a game will necessarily be a successful work of horror. Plenty of well made, immersive horror games lose the audience by venturing too far into the realm of action. (Some of the most widely acknowledged culprits are entries in the same series I earlier cited as successes: Resident Evil 5, Dead Space 3, and the late-era Silent Hill games.) Plenty of horror games that rely on limitations can disappoint by not drawing the player into the experience effectively enough.

And even games that nail both sides of the equation can still fail to deliver worthwhile horror. According to RagnarRox, an experience that delivers effective scares and capitalizes on the most visceral elements of the genre isn’t enough to succeed.

“I personally really don’t enjoy horror stories (be it games or other media) that don’t have to say anything, but only seem to rely on horror tropes for [their] own sake,” he said. “A jump scare can be an efficient tool for conveying an emotion that’s crucial to narrative—or it can be just a cheap jump scare. Violence and gore, used effectively, can be incredibly efficient tools for that as well—but if a horror game is brutal just to fetishize brutality, it’s garbage.”

RagnarRox cited Frictional Games’ Soma and its unsettling existential themes as an example of a horror game that offers something more than cheap thrills. It’s hardly the only example, either. Games like Layers of Fear 2 and Outlast 2 touch upon childhood trauma. 1995’s I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream explores a mix of personal and societal horrors, having the player experience the different personal hells of its characters. Any horror fan could no doubt add a half-dozen or more games to this list.

For Grant, the best horror video games—like the best the genre has to offer in any medium—all tap into a universal and primeval aspect of our shared humanity.

“We love to be scared, to face down the monsters and step bravely into the night taking on the worst nightmares that can be thrown at us,” he said. “It gets the heart rate up—and makes me, as a player, happy to have survived.”

Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity.

Header image credit: Soma, Frictional Games

Michael Pementel is a journalist who works throughout the entertainment industry, covering music, video games, film, and anime. His writing has been featured in PopMatters, Dread Central, Film Inquiry, Substream Magazine, Alternative Press, and more. Throughout his work he looks to analyze the societal and personal impact art has on our lives. Currently he writes for Consequence of Sound, Bloody Disgusting, and Treble Zine.