On a brisk December afternoon in 2019, an unassuming young man stepped up to the podium at the China Indie Game Alliance (CIGA) developers’ conference in Shanghai. Somi, a solo indie dev from South Korea, had come to speak about empathy games, namely his most recent title, Legal Dungeon. While previous guests had stuck to discussing game mechanics, industry advice, and business strategies, Somi’s slides opened with an unexpectedly personal bang. It was a quote from his mother, in big bold letters: “People always want to recreate themselves.”

This piece of maternal wit perfectly encapsulates the heart of empathy games—games that encourage consideration and compassion, often used to teach children how to empathize with others. Empathy games are often used in community-building exercises to encourage people to see things from different perspectives, which can be useful in developing solidarity in teams. But creating empathy in video games is a moral quagmire, and can be highly subjective depending on the player, and as per Somi’s mother, self-replication is often used as a means of seeking understanding. As Julie Muncy put it in a 2018 Wired essay, “An empathy game can make you cry, but it can’t make you care.”

On an emotional level, Somi’s games are difficult experiences. In his own words, they’re not fun. During the day, he works in a law enforcement-related job that he can’t disclose, and at night, he makes games—thoughtful, pixelated reflections of himself and the world around him. As someone who went to law school and works closely with the state machine, he said on stage, “The biggest emotion I wanted to convey was guilt.” The guilt he faces at work is an overpowering part of his life; it almost makes too much sense that he would be drawn to redemptive practice of making empathy games.

Ironically, Somi believes empathy is too much to expect, especially from the police. “I think empathy is impossible… because in different situations, we cannot understand another person’s suffering, even though [we try] to do that,” he told me after his talk. “It cannot be perfect.” Still, for someone whose art is defined by the grim reality of his day job—his games can tackle heavy subject matter—and for someone who approaches game development as a sort of penance, Somi is incredibly friendly and open, with a matter-of-fact sense of humor that starkly contrasts both his work and his world. In interviews, he speaks frankly about drawing inspiration from books like Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother (about overthrowing terrorists) and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley.

The CIGA presentation continued. Somi had carefully prepared for his non-Korean audience, sketching a brief picture of South Korean society, as well as the country’s controversial 2016 Anti-Terror Act, which enabled its intelligence agency to conduct unprecedented levels of surveillance on citizens. The act’s ambigious wording gave it a powerfully invasive scope beyond combating terrorism, and under Park Geun-hye’s troubled presidency, critics were rightfully concerned about freedom of speech and abuse of power. Passed in March 2016, the act was briefly delayed by opposing legislators’ stunning 192-hour filibuster. One lawmaker spoke for an emotional 12 hours and 31 minutes.

And then, Somi presented something you wouldn’t expect to see at a game dev conference—a quote from political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, which followed the trial of prominent Nazi Adolf Eichmann:

The trouble with Eichmann was that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.

Coming from someone working with the law, this epigraph was unusual, to say the least. “The banality of evil” is one of Arendt’s best-known gifts to our collective cultural vernacular, a simple phrase loaded with an insidious weight. Some critics consider Arendt’s approach to be a thin justification of evil, that men following orders, even unthinkably cruel orders, are simply normal people trying to get ahead within a monolithic institution. Indeed, when it comes to trusting and empathizing with the police, Somi—who deals with them in his day job—believes we need an independent regulator. “When there is a police officer, they have power,” he said, “but there should be another organization [to make] the police officer responsible.”

But in the world of South Korean society—one marked by systemic elitism in politics and education—Arendt’s theory made sense. Here were bureaucrats trying to rise to the top of a poisoned system, police officers trying to meet arrest records, and wealthy families giving their children a gilded edge. Here was a corrupt presidential administration that blacklisted politicians and artists (including Parasite director Bong Joon-ho). South Koreans are active when it comes to protesting; in this case, the 2016-17 Candlelight Demonstrations were an expression of dissatisfaction with then-President Park’s administration.

“[Democratic social action] can make nations better,” Somi said. “If we do not express individual opinions, the politicians and the government [can rule] with power just for their initiatives, their personal interest.” In 2019, more protests (and counter-protests) erupted over the perceived corruption of Justice Minister Cho Kuk, as well as unpopular American military demands. Protest in South Korea, as in any healthy democracy, is a form of expression, even in the face of an impassive government.

Credit: Somi

Protest forms the backbone of Somi’s award-winning game Replica, which deals with issues of surveillance, propaganda, and duty. Before starting development in early 2016, he had been immersed in (and inspired by) Sam Barlow’s cult hit Her Story, as well as Lucas Pope’s The Republia Times, in which players control a national newspaper. In the early days, he even thought about incorporating inspiration from The Talented Mr. Ripley—after all, a story about a murderous social climber would resonate well in a society where people were stretching their morals to make it to the top. “At the time, the Korean political situation was really terrible,” he said, recalling the year that President Park was impeached and the National Security Agency clamped down on the media. “So I changed the whole story of the game.” On impeachment day in 2017, Somi made his game available for free.

Replica doesn’t take long to play, just an hour for a single playthrough. The first thing I noticed after finishing one of the game’s many endings is the chilling, deliberately realistic use of authoritarian language. The simple phone-hacking game requires breaking into an alleged terrorist’s cell phone to gather “evidence” in the name of national security, and any deviation is punished. Like an errant child, your character is pressured into doing “the right thing” for the sake of nation and family. It is revealed that the phone’s owner is doing the same thing to your phone, putting a distinctly totalitarian spin on the classic prisoner’s dilemma, in which two people who should rationally work together for the best outcome don’t, due to shortsighted selfishness. The specter of constant state surveillance is familiar to me: I live in a country that’s been rather successful at getting people to dismiss its authoritarian qualities, using similar rhetoric about “the greater good.” Even with its much more extreme scenario, Replica is a not-so-distant cousin who speaks the same language.

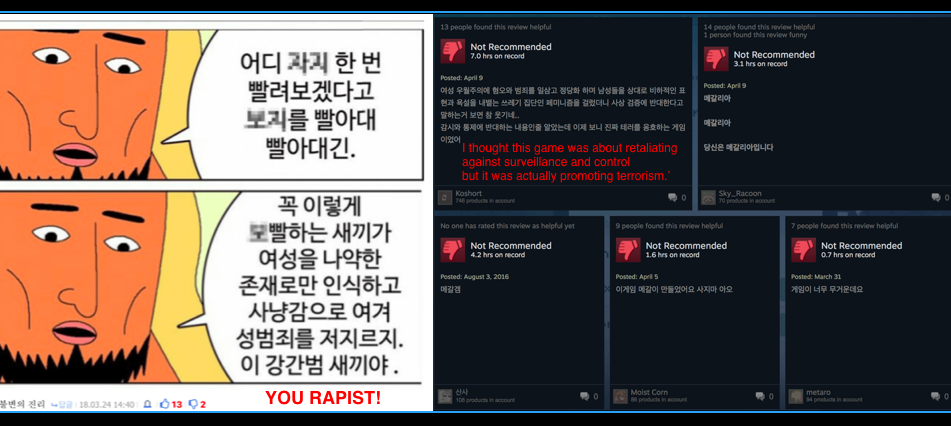

Replica was released in July 2016 to positive reviews that lauded its sharp sociopolitical message. On the homefront, Somi was pleased—a September 2016 Voice of America article even called him “an unlikely political activist.” The game picked up award nominations and Best In Show at BitSummit 2019. But things started to sour. A couple of months later, trolls and harassers started to bomb Replica’s Steam page with abuse. “At the time, a radical right-wing website was very powerful with some backup from the government,” Somi said, referring to the website ILBE (also known as Ilbe Storehouse), a 4chan-like forum that prioritizes user anonymity. “They were curious about me and my game. They were infamous for trolling and sabotage.”

Negative reviews appeared calling Replica a “commie game” made by a “North Korean spy.” Online chatter sprang up about Somi’s real identity, decrying him as a terrorist—on stage at CIGA, he recalled that one commenter even went as far as to call him a rapist. Several Steam negative reviews invoked the slang “maegalli” (메갈이)—a term referring to emasculation of Korean men by feminists, most commonly used among gamers in Korea—even though Replica doesn’t feature distinctly feminist story elements. Soon, everything Somi did was subjected to an undue amount of scrutiny. He recounted an incident where an online mob noticed that he clicked “Like” on gender equality-related news articles. A total of seven likes turned into vitriolic rhetoric about Somi being a radical feminist who hated men and committed crimes. Afraid, he deleted his social media posts about his life and family.

Fueled by the events after Replica, Somi poured the undistilled essence of his work-guilt into a new game based on real Korean criminal cases. Moving into the 2010s, world politics have yawed heavily to the right; Legal Dungeon came out in 2019, a year fraught with major incidents of police brutality in Hong Kong, Chile, Catalonia, and of course, the United States. And while the game is specifically rooted in the police performance system in South Korea, its themes of justice and abuse of power are universal. “Even though the game [focuses] on the small system in the small country of Korea, the main theme… is [that] power can be wielded for private interests,” Somi said. “So it can be applied [to] other countries as well. I think Legal Dungeon has more meaning during this kind of turbulent age.”

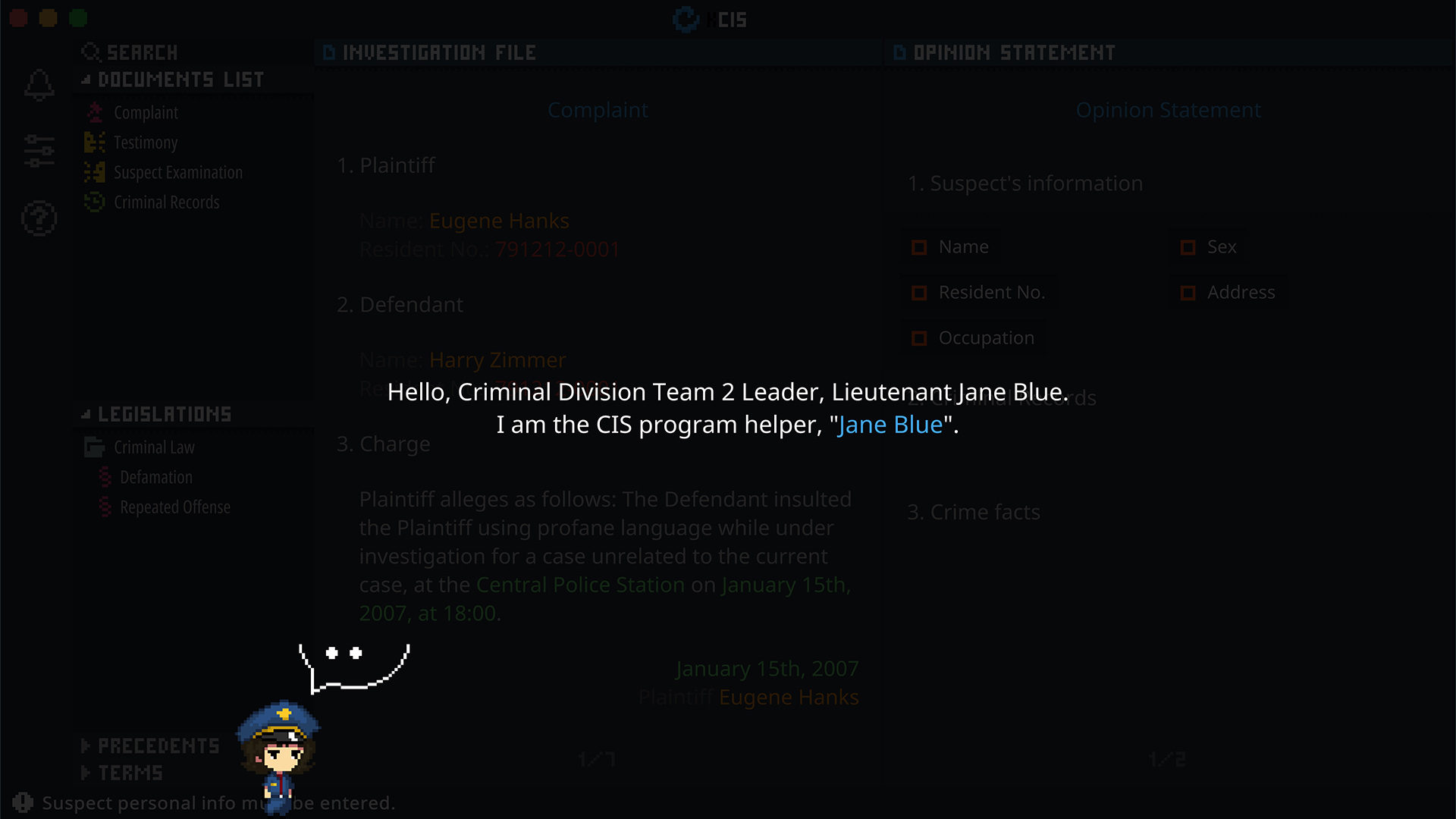

Legal Dungeon is a document-based police procedural where players must do legal paperwork to correctly file a verdict. It starts off pretty innocuously—you play as Jane Blue, a sergeant who must use her investigative training to help prosecutors indict criminals on paper. “Mini Jane,” a sort of Clippy-like desktop assistant, gives you pointers and helps you look up legal precedents in the game’s database. It isn’t just about sorting paperwork—your colleagues in the precinct are also concerned about hitting their arrest quotas and maintaining their performance records, even if it means stretching your ethics.

Credit: Somi

After completing the first case, it becomes clear that filing verdicts isn’t as straightforward as it seems. Even though I had built what I believed were watertight cases, there was still the matter of the sentencing “dungeon,” designed as a turned-based court battle where the accused can defend themselves. In Legal Dungeon’s second case, a grandfather and granddaughter are accused of stealing a stack of free newspapers that the newsstand owner was going to throw out anyway. In round two of the “dungeon” portion—legal arguments—Jane Blue must prove that the stolen property has monetary value, and therefore, taking them constitutes theft. On my first attempt, unable to find legal grounds for the prosecution, I watched as Jane Blue lost hit points, got dragged to a disciplinary committee, and cued the “game over” screen. On my second, I found a court precedent in my favor, but still struggled to choose the correct option for criminal intent. It simply wasn’t that easy to nail down a defendant, all the while feeling like a monster.

“I’ve never heard of someone who enjoyed that kind of power in my game,” Somi said, referring to the human drive to judge and punish others. Most reactions, he said, were from people who wanted to stop playing because they felt that the game was too stressful, or unnecessarily cruel. “I think it is because it delivers the detailed emotions of victims, or the situation, to the players,” he mused. “So I think they feel it. And even though they know what the problem is, there’s not that many other choices.”

One positive Steam reviewer claimed to be a cop who worked at a police box for five years and praised Legal Dungeon as an educational tool. But, as with Replica, not everyone was into it.

While showing the game at Busan Indie Connect, Somi came face-to-face with a cop. “One of the players was very serious, playing my game,” Somi explained. “He was in his thirties, and he was playing just one chapter.” This is the very first case that players encounter in Legal Dungeon, the “Bacon Shit” episode where an angry defendant is prosecuted for swearing at a police officer in front of other people. “He stood up with a [frowning] face. ‘Are you… a cop?’ I said, ‘No, no, I’m not a cop.’ And he said, ‘Why are you making this kind of game?’”

Under Korean law, public swearing is an offense. The crime of “insult” (모욕) is serious because it’s about preserving one’s reputation, as the law prohibits public insults (and even gestures) that can affect a person’s social standing. A police officer on the receiving end of an insult like “Bacon Shit” would stand to lose respect in the eyes of witnesses. Ultimately, insulting a cop is a rarely enforced minor crime, and there’s no clear way to handle it. “Korean police [have] low status because of their historical wrongdoings,” explained Somi. “Most policemen feel very [stressed] because it is a common situation that civilians condemn police in public. So people… say bad words to police, and mostly it is taken without penalty.”

In the game, the “Bacon Shit” defendant is ultimately found not guilty, because the insult was made within the walls of a police station, and only in front of other officers. “There were no civilians around,” Somi said. Therefore, in the eyes of the court, the “victim” didn’t stand to lose his public reputation.

At Indie Connect, Somi went on to tell the man that since the “Bacon Shit” incident was based on a real court ruling—a legal precedent—it could be used anywhere, even in games. This didn’t help. “I don’t want that kind of precedent [to] be read by civilians… because they can know when and where to coerce police officers,” the man said to Somi. “Detailed information should not be delivered to people. So, yeah. I hate your game.” And just like that, he left.

Another incident involved a famous Korean streamer, 풍월량 (@hanryang1125 on Twitch), who decided to stream Legal Dungeon. At the time, this was great news. “It [meant] that when he [played] my game, many people [would buy] my game so I can be rich,” Somi smiled. During the stream, someone popped into the chat and typed, “Hey, the developer of this game is a very serious radical feminist. Do you know that?” Things came to a grinding halt; Somi hadn’t been watching the livestream, but someone emailed him screenshots afterwards to warn him about online hate. “[@Hanryang1125] stopped playing the game, and he didn’t post his playing on YouTube because he was worried about trolling,” Somi recalled. “I lost my chance.”

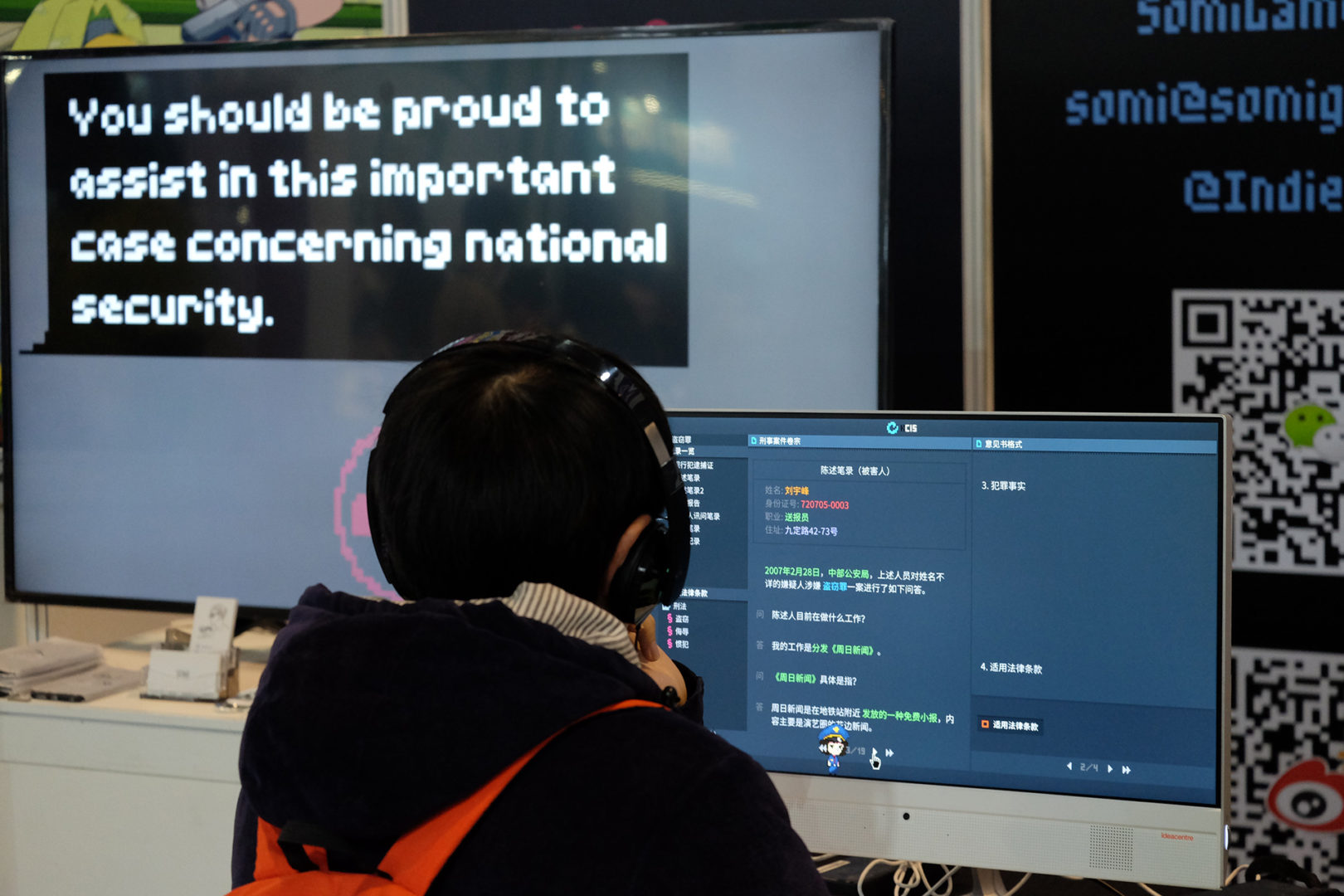

Credit: Alexis Ong

In many ways, Legal Dungeon is a deeply personal journal about police work, prosecution, and the innate human drive to pass judgement. “If I had stopped after Replica, I wouldn’t have made Legal Dungeon,” he said. “I kept going because I know that empathy is limited by each person. Two people can have different reactions based on their experiences and imagination. I am no longer worried about player reactions. What’s important is that I keep going.”

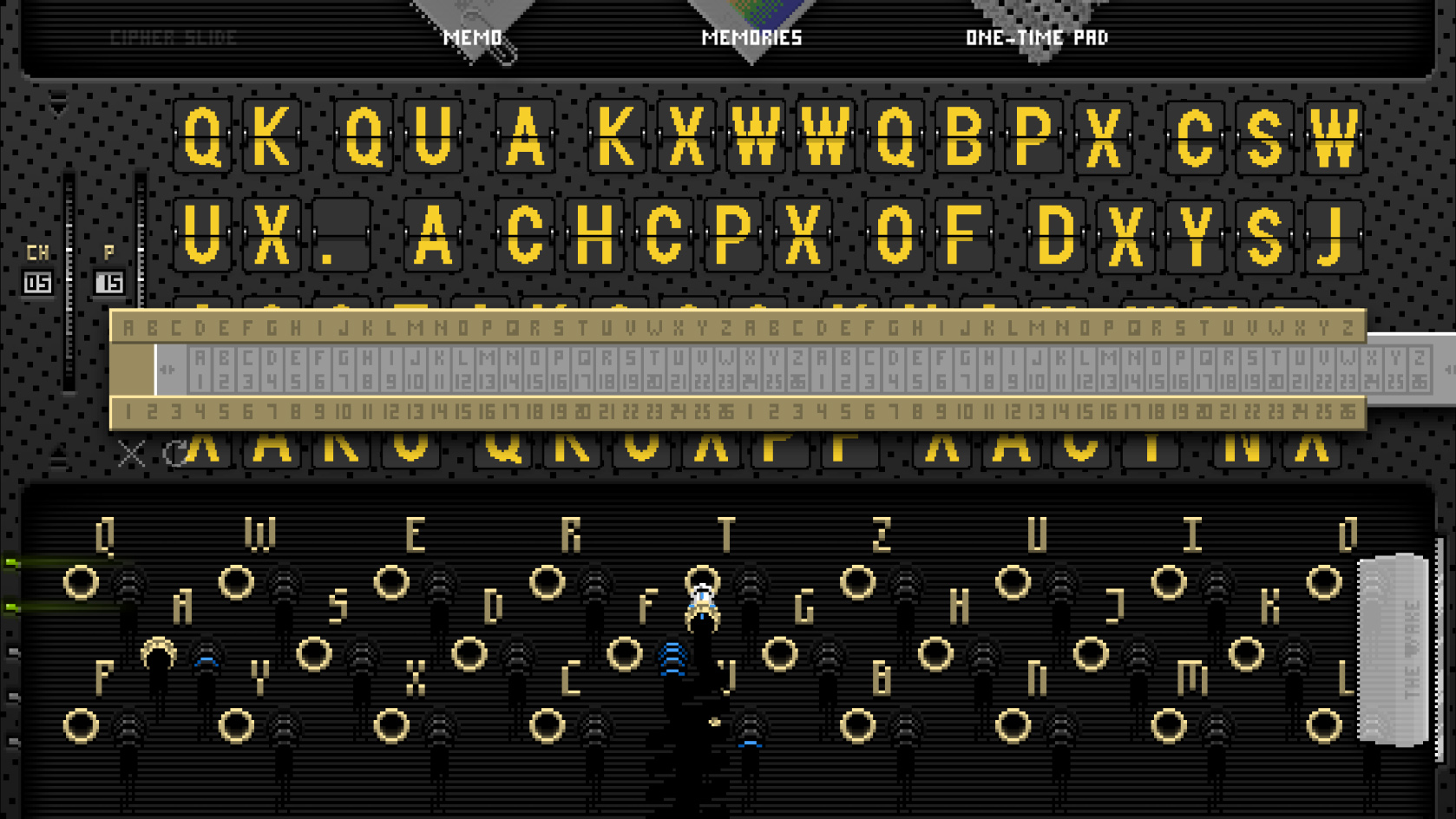

Pondering his next steps at CIGA, Somi considered making a game about feminism and censorship. “I was thinking about making a game about gender issues… about the diversity of gender,” he said. “I was trying to learn about the life of Alan Turing. I was really interested in his life, and especially how he died, and the coding machine called Enigma.” He initially intended to focus on Turing and his (in)famous machine, but during his research, Somi felt like he couldn’t fully represent the suffering experienced by marginalized genders or sexual identities. “I was trying to understand what they [felt], but it was not perfect,” he said. “So I felt guilty about that. I changed my mind. I just [concentrated] on my own experience, my own thoughts.”Following a thread of inspiration from learning about the Enigma, Somi turned his idea into a personal project about his childhood. “It is very ironic,” he said of his decision to lay bare his personal life after the harassment experienced with Replica.

The Wake: Mourning Father, Mourning Mother will be the third and final installment of what Somi calls his “Guilt Trilogy.” Since game development is his way of journaling, the autobiographical game takes place, quite fittingly, in a journal that must be decoded with a substitution cipher. “I’m always saying that [a] game is like a diary,” he explained. “I thought that the last one could be a real diary in the form of a game. It has my story and my family pictures.”

Tentatively scheduled for release in April, The Wake follows the events of a three-day funeral, exploring the guilt woven into the memories of a multi-generational family. This is undoubtedly Somi’s most personal game, touching on his own feelings about being abandoned by his father. That said, he doesn’t seem concerned about sharing these intimacies with players. “The sad part, is that I’m sure the game [won’t] be popular at all because it’s not fun at all! I have to complete the game as soon as possible and make something enjoyable,” he joked.

Credit: Somi

Toward the end of his CIGA talk, Somi wound down by saying that he would continue to report on Korean culture and continue making games—a curious expression for someone so private. “I’m not trying to make games that [focus] on society,” he said. “I’m focusing on myself and my feelings. When I feel a sense of guilt, I make a game that [conveys] that sense of guilt to players.” Replica wasn’t born out of his need to tell a Korean story, but to tell a story about his guilt, an approach he tries to emphasize. But working with law enforcement isn’t a choice that begets a clean conscience; for better or for worse, it produces deep-seated emotions about enabling an ever-present, violent part of the modern state. How could his games not touch on society and politics? It’s also impossible to fully appreciate Replica’s message without experiencing it in its native language. In the translation process, Somi said, “a lot of detail and nuance of meaning [was] lost.” In the end, it seems that all roads lead to guilt.

Afterwards, a woman raised her hand and stood to ask—a hint of puzzlement in her voice—why Somi chose to express himself through games. Why not easier forms of media, or something more “suitable” for his message? With monk-like patience, Somi explained that in high school, he drew cartoons, and in college, he wrote novels. And while striving to achieve empathy will always be an uphill challenge, through games, players can actually step into the shoes of other people.

“If I just write things about the suffering of others and the sense of my guilt, if I just drew something, it cannot be effectively sent. Emotions cannot be sent to people. I wanted to make people feel the same situation, the same atmosphere that suffering people are in,” he said. “All media, even my games, cannot be detached from developers’ thoughts and feelings. I just want people to think.”

Header image credit: WePlay. Thanks to Michelle Lim for translation assistance.

Alexis is a freelance journalist based in Singapore. She has a soft spot for abandonware and old point and click games, and once tried to set up a bot shop in Diablo 2—sorry, Blizzard. She lives on Twitter at @steppinlazer.