For Navid Khonsari, the turning point came during a 2006 trip back to his home country of Iran. While there, he encountered a young woman playing Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto III, the groundbreaking open-world title on which Khonsari had served as motion capture director. As he watched the Iranian woman play, she told him she thought America must be an incredible place to live.

It wasn’t a response Khonsari expected. At the time, the U.S. occupation of Iraq was in its third year, and anti-American sentiment was high throughout the region. So he asked what, exactly, she meant. When she played GTA III, she answered, she experienced freedoms that were nonexistent in Iran, those had been largely lost when the the 1979 Iranian Revolution overthrew the Western-backed Shah and installed a new Islamic republic.

“She had the ability to drive around, to listen to whatever music she wanted to, to go to stores and buy whatever kind of clothing she wanted to, to go and workout,” Khonsari said. “When I saw the way this young woman was looking at me and playing GTA and what she was getting out of it, at no time did she talk about the shootings, or the crazy missions, or any of that kind of stuff.”

Credit: Rockstar Games

By showing him that games could have a positive social impact while still offering entertainment, the conversation changed the trajectory of Khonsari’s career. “I saw the impact that games like GTA had by being embraced by audiences as showing the power of gaming. I don’t think there’s anything as comparable to gaming that is as immersive. And entertainment is a fantastic path for gaming, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be the only path,” he said.

Later that year, Khonsari left Rockstar, where he’d worked on five GTA titles, as well as games in the Max Payne, Red Dead, and Manhunt series. With the help of his sister, he founded iNK Stories, a production company that works in films, games, and virtual reality. To date, its best-known work is 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, a 2016 adventure game set during the Iranian Revolution, which Khonsari had witnessed firsthand as a 9-year-old boy.

“I took the lessons that I learned at Rockstar, making high quality games with real immersive narrative, stories, high production values and made a drastic change in my work, which was towards the nature of the content,” he said.

Credit: iNK Stories

1979 Revolution takes place in Iran’s capital city, Tehran, at the outset of the revolution. The protagonist, Reza, is a shooter, though his weapon is not a gun but a camera. The story unfolds through flashbacks, with Reza developing pictures he took during the protests. Scenes of tense confrontations with both police and protestors show the dangers of documenting a revolution and the ambiguity of life in a conflict zone. The blurring of right and wrong is on full display.

In the game, Reza’s photographs are collected in a journal and displayed alongside actual images from the revolution, allowing the player to bear witness to a historical event in similar fashion to the work of a real-world photojournalist or documentary filmmaker.

In Khonsari’s view, the approach offers a chance to spark a more mature and nuanced social consciousness, one guided by empathy. “We can take a look at real-world events and bring that into the immersive world of games and be able to entertain and engage and shed light on stories that form our present day world by looking at the past,” he said. “And not just make them shooters such as the Call of Dutys, but to shed light on different people, and how their stories are really no different than ours.”

Credit: iNK Stories

When I spoke with Khonsari in late 2019, he had just made 1979 Revolution available for free in response to the ongoing protests in Iran that have left over 1,500 people dead and led the government to temporarily shut down the internet in hopes of disrupting the communications of dissenters.

“In terms of activism, [we are pushing for] more and more games to make statements. To be honest, there’s this consensus that’s coming from some groups that games and politics should not be mixed together. And I feel that I’m particularly enjoying the work that’s being done by young designers that are creating experiences that don’t exactly follow a typical template, and are breaking all of these boundaries in terms of what the game is,” he said.

“If gaming has no place for politics in the world that is ever-changing right now… then gaming is nothing other than just a frivolous experience.”

Designers aren’t the only ones pushing the public to view games as more than just a frivolous experience, either. The artists Joseph Delappe, through his project dead-in-iraq, and Anne-Marie Schleiner, through her Velvet-Strike, created pioneering works of what are known as “online game interventions.” The pieces are still being exhibited at major art galleries and museums to this day.

Inspired by watching a public reading of those killed in the 9-11 attacks at the site of the World Trade Center, Delappe wanted to do something similar for all the fatalities in the Iraq War. He chose the online version of America’s Army as the appropriate venue. The game, the first version of which launched in 2002, is a multiplayer first-person shooter developed by the U.S. Army to increase recruitment.

Delappe would log into the game with the account name “dead-in-iraq” and then stand in a vulnerable position, waiting to be killed. He would then type into the in-game chat the name, age, service branch, and date of death of soldiers who had died in Iraq. One at a time, by hand, he typed these names until his avatar was killed, and then continued after death, typing more names while waiting to respawn.

Delappe began the project in March of 2006, the third anniversary of the start of the Iraq conflict and ended it in December of 2011, the official withdrawal date of the last U.S. troops in Iraq. Over more than five-and-a-half years, he entered a total of 4,484 names.

Other players in the game responded with messages of “wtf?” “what is this,” “go away,” and “stfu”—internet shorthand for “shut the fuck up.”

“I would get those types of messages all the time: ‘This is just a game’, and ‘We come here to get away [from] all of those types of ideas and thoughts and politics,’” Delappe told Roger Stahl in his documentary Returning Fire. The 2011 film documented Delappe and Schleiner’s process and the response they received during the projects.

“These kind of games have been amazing in terms of their cinematic quality with their ability to depict very seductive images of the destruction of war, but it is candy-coated. It is not the real thing at any stretch, and I think in particular with the America’s Army project the level of violence was intentionally designed into the game to allow it to get a rating where any 13-year-old could download it without parental permissions, so it’s really sanitized,” he told Stahl.

When dead-in-iraq began receiving coverage from mainstream news sources like Wired, CNN, and NPR, there was a significant backlash from gamers, some of whom called him a traitor and threatened him with physical assault.

Credit: U.S. Army via Joseph Delappe

“It’s been a 50-50 thing where people have been extremely angry at me or extremely supportive, which I think really represents that divide that still exists in our country,” he said in Returning Fire.

A few months into the project, Delappe received a lengthy email from the brother of a soldier who’d been killed while serving in Iraq. The brother wrote that while he was respectful of Delappe’s work, he didn’t agree with what he was doing and he didn’t think his brother would, either. He believed dead-in-iraq trivialized his brother’s death. “America’s Army trivializes what it means to be a soldier, and what it means to be in war,” Delappe replied at the time.

Velvet-Strike, Anne-Marie Schleiner’s 2002 intervention into Counter-Strike, received similarly harsh feedback. The project was a modification of Valve’s online first-person shooter that allowed players to spray anti-war graffiti instead of bullets.

“Velvet-Strike did receive some violent, personal and misogynistic threats [from gamers] and pushed some buttons right at the political divide that has in recent years only worsened in the U.S. between right and left—but our response was not death threats in return but humor and pranks,” Schleiner told me.

After a montage of clips from Velvet-Strike was chosen for to be included in the Whitney Museum’s 2004 Biennial, art critic Jennifer Buckendorrf wrote in Salon that the project carried a whiff of futility. “No matter what kind of criticism artists like Schleiner manage to voice, militarism will most likely prevail in the gaming world, unless the critics start getting a lot more creative. The plain truth is that commercial games are better and more engaging than their cobbled-together, pro-peace counterparts. It’s just more fun to blast away.”

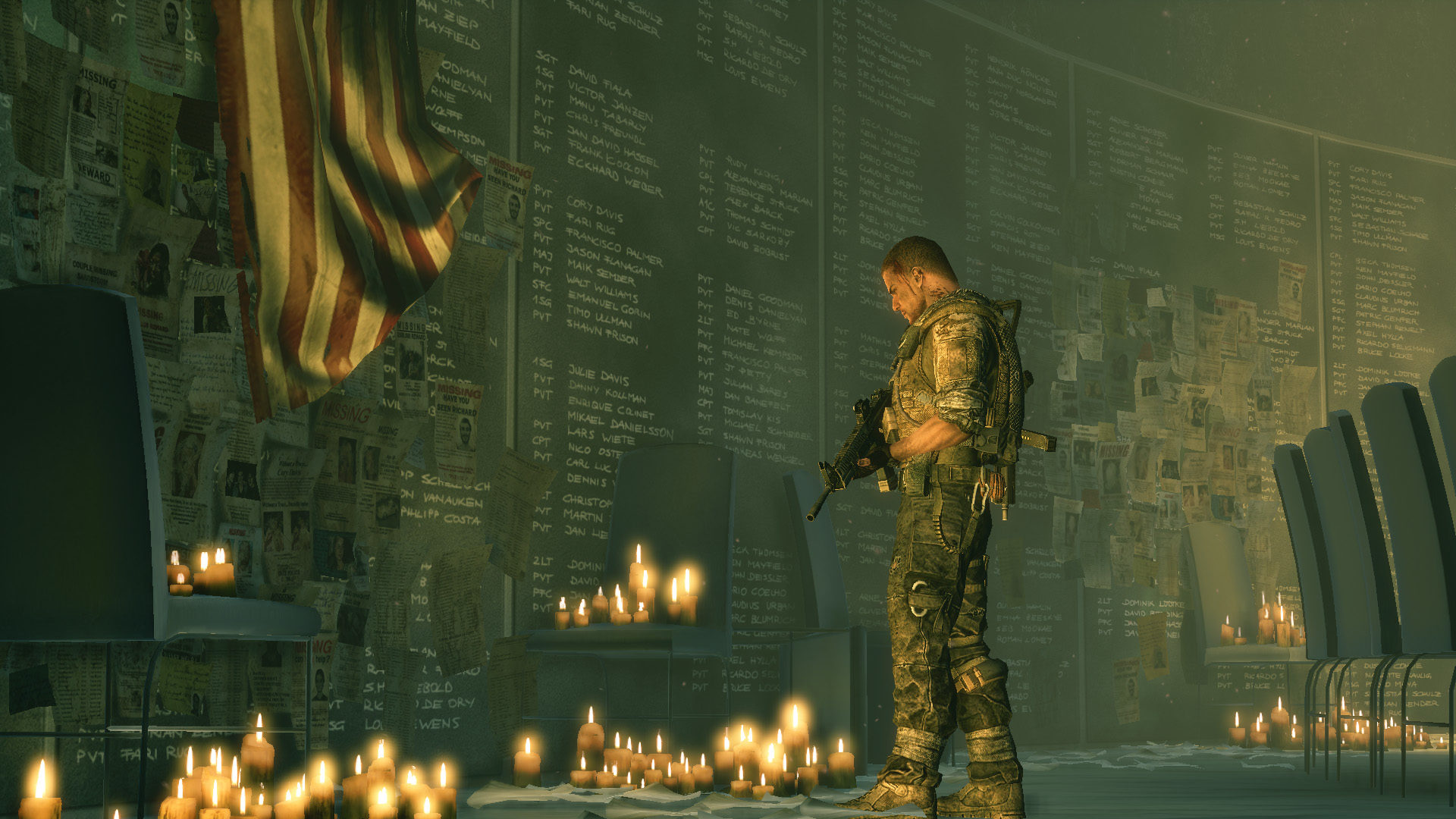

Before he wrote Star Wars: Battlefront II, Walt Williams was the narrative designer and co-writer of Spec Ops: The Line, one of the first and only big-budget games from a mainstream publisher to address war with moral ambiguity. Though regarded as a commercial failure, the 2012 game garnered critical acclaim for its narrative, which took direct influence from the Joseph Conrad novel Heart of Darkness and the Vietnam War film it inspired, Apocalypse Now. The game remains highly acclaimed today as an experience that sets itself apart from what Ars Technica’s Kyle Orland called “the long line of indistinguishable, mindless, testosterone-fueled, ‘kill-anything-that-moves’ war games in the vein of Call of Gears of Medal of Duty Honor War.”

The Line follows Captain Martin Walker and his elite team of Delta Force fighters on a recon mission into Dubai after an epic sandstorm has wrecked the country. Martin experiences hallucinations throughout the game, and The Line pulls no punches with showing the true horrors of war.

Credit: 2K Games

A standout example is a scene where the player has no choice but to use incendiary mortars full of white phosphorus to unintentionally annihilate a group of refugees. PC Gamer critic Samuel Roberts described the scene as showing “the full extent of the carnage: charred corpses everywhere and the distressing image of a dead mother hugging her child, both burnt alive. If Call of Duty did this, there’d be uproar. It’s to the credit of Yager, the developer, that the context justifies the horror in this case.”

Since its release, Williams has been consistently asked if The Line is an activist game with a pacifist message. He has maintained that his focus was not anti-war as much as asking gamers who may have been against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to question why they play games that virtualize war for fun.

“I’ve never considered Spec Ops: The Line to be an activist game, because I don’t consider it to be about war,” Williams told me. “To me, it is about video games. Specifically, how we lie to ourselves when playing a video game, suspending our belief in order to achieve positive sensations of adrenaline, control, and success. In the military genre, those sensations are wrapped up in a veil of duty and heroism, turning a harmless piece of entertainment into a vessel for militant, jingoistic ideologies. The story isn’t about war. It’s about how we deny what we know to be true about war—in short, that it is hell—so that we can literally see it and enjoy it as a game. If Spec Ops comes across as anti-war, that is because we tried to present it as emotionally truthful as we could, rather than treat it as a game.”

Credit: 2K Games

The aforementioned documentarian Roger Stahl’s most recent book, Through the Crosshairs: War, Visual Culture, and the Weaponized Gaze, traces the history of the gun-camera and examines the ways that the public has been increasingly invited to picture war through the weapon’s eye.

He believes The Line to be the most activist-minded game in the last decade. “It forewent the jingoism of most war games and instead focused on the existential angst of the soldier. I would compare it to the [2005] movie Jarhead in a lot of ways. It explored gray moral territory and difficult dilemmas. It also challenged the ‘clean war’ aesthetic of most games and introduced gruesome scenes of dead civilians (charred women and children clutching each other in a bombed-out house). So it may have qualified as an ‘activist game’ insofar as it broke with the genre,” Stahl told me.

“In reality, perhaps, it was just capitalizing on disillusionment with the real wars over in Afghanistan and Iraq and delivering a soft critique. It was less about war crimes against Iraqi civilian victims and more about the victimized psychology of the Western soldier/military. This kind of frame was common in post-Vietnam cinema in such nominally anti-war films as Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket. With Spec Ops: The Line, it appears in game form in the shadow of an unpopular war.”

Telling hard and ambiguous stories where there is no clear right and wrong may or may not effect social change directly, but it can offer a meaningful perspective on the effects of war in both the real and the virtual worlds. The impact of titles like Spec Ops: The Line on individual players is difficult to measure, but they do have a direct influence on the industry in another way: inspiring other designers to take similar risks.

Credit: 2K Games

This War of Mine, released in 2014, asks players to help a group of civilians as they try to survive in city torn apart by war. Co-writer Paweł Miechowski told me The Line was a major inspiration for their design team. “The Line is a game that we remembered for being in fact a brutal depiction of war and having an anti-war message after one of the storyline twists. That was one of the first, if not the very first, attempts to treat a game like a mature form of storytelling,” he said.

This War of Mine, in turn, is one of two games cited by Navid Khonsari as an influence on 1979 Revolution, along with Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please. “There were definitely those games that were broaching serious subject matters and were able to be successful by being engaging, but in many ways we didn’t have a lot of games to look at. We definitely looked towards literature, towards documentary film as being key, and theater, and all kinds of activism in other kinds of creative outlets,” Khonsari said.

Walt Williams agreed that few big games today offer pointed social critiques or truly thought-provoking stories, sharing what he saw as the reasons behind that disconnect. “There are easier, more accessible ways to experience art that will challenge your sense of self. Furthermore, there are cheaper ways to create that art. And to take it one step further, there are more reliable ways to make a living than disrupting your audience’s view of the world every time they pick up a controller.” Big-budget games are, by economic necessity, mass-market entertainment before they are anything else.

“They can, and will, push the envelope,” Williams said. “But only very, very rarely.”

Header Image: iNK Stories

Hart Fowler is the former publisher of 16 Blocks Arts and Culture magazine. He currently works as an independent journalist for both national and regional magazines. He recently has been writing about the opioid crisis, war veterans, art, podcasting, and outdoor recreational sports. His recent collaborative efforts in short-form fiction are currently in the works to be published in both print and podcast form. You can see some of his work at hartfowler.com. Follow him on Twitter @JHartFowler.