This story contains spoilers for Control.

The Tennyson Report

Among the many documents, audio recordings, and videos scattered around the offices and laboratories in Control, you may stumble across a file called “The Tennyson Report.” Like much of the textual lore, this anonymously authored document hints at discord within the game’s fictional clandestine agency, the Federal Bureau of Control.

The report begins with a striking sentence: “For years, the Federal Bureau of Control has been wrongfully forcing a philosophy upon itself and its people. This philosophy is known to you all as ‘science.’” The Bureau’s mission is to identify and collect paranormal phenomena and then bring them to its headquarters, the Oldest House, for containment and study. But for the insider behind the report, a scientific approach to the paranormal makes no sense. If you’re dealing with things that by definition subvert scientific laws and rational explanation, what good is science? Shouldn’t paranormal objects instead be treated as arcane and mystical?

The obvious response here, from a scientific perspective, is that all things appear arcane and mystical until we figure out what makes them work. That’s the point of science. How many features of reality that we didn’t understand and were previously subject to religion and superstition have since been rationally explained through scientific study?

It seems the Tennyson Report is calling for a retreat into religion and the past, not least in referencing 19th century poet Alfred Lord Tennyson and quoting from his poem “Tears, Idle Tears”: “So strange, so sad, the days that are no more.” The friction between past and future, religion and scientific advancement, is a theme in a number of Tennyson’s works, sometimes as a lament for what no longer is or concern over an increasingly dominant scientific rationality.

But it would be rash to dismiss the report as merely a nostalgic call for faith. It goes on to explain that the Bureau’s methods “create the illusion of a scientific structure; a tidy little system,” and that, within that system, “if a thing cannot be quantified, then we dismiss it outright.” The worry is that the scientific desire to clinically measure, define, and control things, even when they belong to an alternate reality, has itself become an oppressive orthodoxy.

Who’s in control?

It wouldn’t be much of an observation to say that Control is about control. From the title of the game to the name of the Bureau, it’s hardly a covert theme. But maybe that’s the point. Concepts of control run through it in so many interlocking ways that they merge into a kind of background noise. The word refers to so many relationships and details in the game that it’s impossible to settle on any one interpretation.

We might think about the tension between player agency and the directed linearity of our progress—a common theme in games. We control the protagonist, Jesse Faden, determining her moment-to-moment fate as she explores the Oldest House. But we also operate according to clues or mission objectives that control the overall aims of our movements, while the level design carefully employs corridors, elevators, blocked doors, and open spaces to control our routes.

We might also think about how we interact with Jesse and, through her, the game world. To advance, we must learn to control Jesse’s powers, which enable her to control paranormal objects. As we get used to the controls, we become more proficient at shooting, throwing projectiles and shielding ourselves, abilities that all involve Jesse learning to better control herself and the environment. To beat the enemy—mainly Bureau employees controlled by a mysterious paranormal force called the Hiss—we also need to carefully control our ammo and paranormal energy levels.

There’s plenty to think about in the game’s narrative as well, not least the curious early twist that sees Jesse become the new director of the Federal Bureau of Control. Having come to the Oldest House to look for her missing brother, Dylan, with no knowledge of the Bureau itself or its procedures, she has to take control of the organization and the unfolding Hiss outbreak.

But then you may often feel more like a trainee than the boss. It’s the NPCs, your supposed subordinates (along with the mysterious Board), who tell you where you should go and what you should do. As with any management job, while you may have control over certain decisions, there are various duties and higher-ups that control you.

Even when, finally, Jesse takes control of her fate and decides for herself to remain as director, there’s a sense that she’s been controlled and manipulated into making that choice. At this point we know that Jesse was always a subject of interest in the Bureau’s Prime Candidate program, which hoped to bring suitably talented individuals to the Oldest House and train them to take control of the Bureau. And now they’ve got what they wanted.

In a sense, the game’s critical path almost seems like an internship, or a controlled test, training her and us on the job for the permanent role. Now, to control what’s left of the paranormal outbreak, the Oldest House must remain sealed to the outside world, with Jesse inside. She may be the director for real now, but she still has no freedom to control where she goes.

Add to all this the matter of an otherworldly being, Polaris, that seems to be part of Jesse’s consciousness (who’s in control in that relationship?), and you could make yourself dizzy trying to answer the question of what the title of Control refers to. Is it Jesse? Her powers? The Oldest House, the Board, the NPCs, Polaris, the Hiss? You? Perhaps all of these; likely a few more.

Science as control

Or perhaps it’s the wrong question. Perhaps looking at the details distracts us from the bigger picture. Perhaps, as the Tennyson Report suggests, the real control here relates to science, or at least how it functions as a philosophy and worldview.

It’s easy to think of science as this neutral mechanism by which humans achieve progress, especially since that’s what we’re often told. But as many philosophers (and some poets) have realized, it’s not that simple.

One way of looking at it is to consider the relationship between science and nature. The more science studies and understands nature, the more able we are to manipulate it and protect ourselves from its various forms—wild animals, diseases, natural disasters. We thus come to dominate nature, or control it, which gives us, through science, power to exploit and destroy it.

What science does, then, is always a matter of who controls it and what they want to achieve. As German philosopher Herbert Marcuse saw it, the “neutrality” of scientific method actually always exists within the context of a practical purpose. For Marcuse, the Western scientific tradition aims at reducing the world to precisely calculable properties and relationships, turning everything into mathematical formulae to be used and controlled. How this knowledge is used then depends greatly on which interests control the direction of scientific inquiry.

Another German philosopher and colleague of Marcuse, Jürgen Habermas, approached the issue from a slightly different angle. For him, this aim of reducing objects to properties and working out how to control them was at the core of science. The problem was that this kind of thinking had begun in modern times to expand beyond science into social life.

This led to what Habermas called “technocratic consciousness,” a kind of rationality that acts in all areas of society as a “glassy background ideology,” “makes a fetish of science,” and “justifies a particular class’s interest in domination.” It’s a mode of thought that applies a scientific perspective to everything, not only nature but people and societies, as objects to be dominated and controlled.

When science is used as a way of organizing society according to the desires of those at the top, it helps to maintain existing power structures and hierarchies. In capitalism, of course, the big desire is maximizing profit, which comes to determine what scientific research is funded, and views every part of the world and society as an instrument to realize its end.

These are the conditions that lead to the infamous Goldman Sachs approach to medical research and its fateful question: “Is curing patients a sustainable business model?” It seems irrational, but it’s the pure dispassionate rationality of maximizing profit here that cuts out social needs from the field of medicine. Science is directed away from the crucial breakthrough of finding cures, and a “scientific” logic of economic efficiency is used to justify it.

Object or subject?

Control creates a similar situation. Its themes go beyond the usual sci-fi trope of scientific hubris, in which scientists develop a God complex and then lose control, to consider how science as a logic or philosophy is itself problematic.

The Bureau, representing state power, uses science to control public perception, in order to maintain existing power structures. The Bureau’s science denies the existence of paranormal items and events, and erases all evidence of them from the world. It then subjects the so-called “Objects of Power” it finds to conventional experiments, attempting to define them within established concepts of scientific thinking.

The one thing this scientific inquiry is incapable of analyzing is itself, to consider whether it’s the best method for every situation. Instead, any paranormal objects that make science appear inadequate must be repressed and controlled. For the ordinary public, the dominant scientific rationality—or technocratic consciousness—that applies to human affairs as well as laboratory experiments is never disturbed. The tidy little system is maintained, because the mess is rendered invisible.

And what does all this mean for Jesse, or for us, both as players and as individuals in reality? From the Bureau’s strictly scientific point of view, people are all simply objects to measure, define, and control, whether they’re Prime Candidates or ignorant members of the public. But at the same time people are also conscious subjects, with their own complex desires, values and feelings that might resist manipulation.

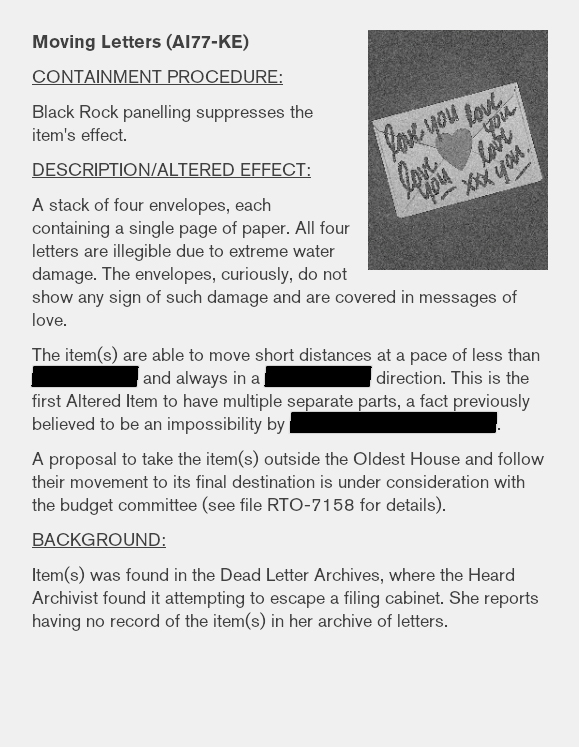

If we look at Jesse’s role in the game, it seems the Bureau sees her as another Object of Power, albeit a special one. The Bureau treats all paranormal objects, from rubber ducks to slide projectors, in the same way: locking them inside the Oldest House to study and control them. The Prime Candidate program follows the same logic but for humans; Jesse is an object of study and a potentially useful tool if she can be controlled.

As director, Jesse then becomes the perfect enforcer to preserve the charade of science, but she is also still an Object of Power, or an anomaly that proves science wrong. With her abilities, Jesse is able to neutralize other Objects of Power that have got out of control, making them fit back into dominant perceptions of normal behaviour. But in doing so she becomes more powerful herself, giving her the potential to reveal the lies of the Bureau’s science and really take control.

As the game’s story has it, Jesse chooses to keep maintaining the existing order. She accepts the need to keep herself and the other paranormal phenomena hidden from public view, and to continue helping to study and control them as much as possible. As players we are then also controlled by the narrative into becoming enforcers of the system. In the name of science and the existing social order we ensure that the truth remains hidden.

Yet Jesse is still the proof that this order is full of contradictions. She is the excluded and marginalized element in society who actually has the power to change things. She, as a subject rather than an object, can be an agent of change. She can choose to keep that which is different, frightening and hard to understand hidden and oppressed (which she does). Or she could choose to make it known: to challenge those in power and the “science” they use to control our reality.

All images: Remedy Entertainment, 505 Games

Jon Bailes is an independent games critic and researcher from the U.K. He is author of Ideology and the Virtual City: Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism (Zero, 2019). You can follow him on Twitter @JonBailes3.